More Than A Game: Blackburn vs Burnley

Andy Mitten gets in amongst one of the North West's fiercest derbies...

“I set foot in the town of t’bastards very rarely: yesterday, 2000 and 1977. It’s a town that time’s left behind. I’ve been to a few dumps and desolate areas, but this place is on a par with the Gaza Strip, Lagos and Banda Aceh. We must build a wall around the hovel, with Israeli-style passport controls.”

The ‘hovel’ that the writer, a Blackburn fan, describes with such venom, is Burnley. His diatribe was posted on a fans’ message board the day after the towns’ two football clubs played out a fiercely-fought draw in the FA Cup fifth round in February.

The game, though scoreless, was not without incident. A Burnley player was struck by a coin and three separate pitch invasions soured the tie. One intruder ran around the pitch with a flag, a second exposed his shrivelled manhood while breakdancing naked. The final intruder, a 42-year-old convicted Burnley hooligan, headed straight for Blackburn’s Robbie Savage.

Millions of BBC viewers saw him offer to fight the Wales international. A potentially interesting bout was prevented by burly Blackburn defender Ryan Nelsen, before the moron scuttled to the touchline, assaulting two police officers as they arrested him. He was jailed for five months and given a football banning order for 10 years.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Blackburn manager Mark Hughes, who compared Blackburn-Burnley (England’s oldest derby, first played in 1888) with Real Madrid-Barcelona and the Manchester bunfight, was apoplectic. “What if he’d had a weapon with him?” fumed Hughes. “God forbid, he could have been carrying a knife. With all the increased policing and stewarding in place, that was disappointing. For three people to encroach on the pitch was poor. That sort of thing should not happen in this day and age.”

With tensions raised still further, the replay was set for March 1.

Eight miles separate the East Lancashire town of Burnley (population 89,000) from Blackburn (115,000). The textile mills which turned the wheels of the industrial revolution and made these areas prosperous have long gone, leaving behind a post-industrial decline that has had a corrosive effect on the social and economic fortunes of both towns. European money has been invested in the region as it tries to shed the cloth cap and whippet, Hovis bread commercial image so often reinforced by visiting journalists, but the 966-page Rough Guide to England doesn’t find space for even a passing mention of either town.

“Blackburn may not be a hip town,” explains die-hard Rovers fan Chris Riley, 27, before the replay. “But Burnley is a throwback to the 1950s. They’re socially inferior to us – I can imagine them pointing at planes. When we played them in Burnley in 2000, they couldn’t get at us because there were so many police – so they started smashing up their own town instead.”

It’s true. To this day Foreign Secretary and Blackburn fan Jack Straw still teases Burnley follower and former Labour spin doctor Alastair Campbell with the taunt: “Wrecked your own town centre lately?”

“They don’t even speak properly,” adds another Rovers fan, Paul Doherty. “We say ‘turf’, as in Turf Moor, they say ‘toff’. What’s that about? Burnley fans just don’t get it. They once played here and tried to destroy the Darwen End by climbing on the roof and throwing bits off it. You know where they threw the roof tiles? Onto their own fans.”

Blackburn fans call their Burnley counterparts ‘The Dingles’ after the social misfits in the ITV soap Emmerdale. So it was difficult when Chris Riley’s closest friend was offered a contract to play at Turf Moor. “Phil Eastwood,” says Riley. “He played for Burnley between 1995-2000. A member of my family, who knew he was my best mate, used to cross the street to avoid him. He refused to talk to him and spat on the floor whenever he saw him.”

Former Blackburn midfielder Mark Patterson can relate to that tale. A local lad, he came close to signing for Burnley in 1996 and was pictured in his ‘new’ club shirt before the deal fell through. When the two clubs were drawn together recently the picture resurfaced. “I’ve been crucified for it,” he says. “I never thought it would come back to haunt me.” And Paul Ince thought he had it bad when he posed in a Manchester United shirt at West Ham.

FourFourTwo is talking with Riley and three mates in a McDonald’s close to Ewood Park. A public house would have been preferable, but those not closed down by the police as part of their ‘Category C Plus’ security operation are for regulars only.

“C Plus games are very rare,” explains a Blackburn spokesman. “But this is a highly unusual and complex match. There will be a significant police presence, with extra officers drafted in from all over Lancashire. There will be a winner so we will have a lot of happy people and a lot of upset people and we are advising Burnley fans that Blackburn town centre is not the place for a post-match drink. It is a derby with a certain history attached and it has added complexity because it’s a night match.”

Both clubs have a rich pedigree stretching back 125 years or more. Blackburn were formed in 1875, seven years before Burnley. When the clubs first met in a friendly, Blackburn won 10-0 and by the time the Football League was formed in 1888, they had already won the FA Cup three times.

When Burnley finally beat Blackburn for the first time, in the Lancashire Cup final of 1890, their victorious players were rolled back through the town on a wagonette. They were proclaimed the best team in Lancashire – which to the locals was a synonym for the best team in the world.

The enmity flourished. A game between the two clubs at the end of the 19th century had to be stopped because of crowd violence. Yet the rivalry between the clubs defies a rational, geographical explanation, and has waxed and waned over the decades. Blackburn could just have easily crossed swords with Preston North End to the west or Bolton Wanderers to the south.

For Burnley the choice was simple. With Yorkshire to the east and the Pennine hills to the north and south, they had to direct their invective squarely west towards Blackburn.

Both were founder members of the Football League and have been crowned champions of England, Burnley most recently in 1960. The Clarets played in the top flight until 1976, before sliding down the divisions and almost out of the Football League in 1987. Blackburn often played in a lower league than Burnley and for a time the two clubs co-existed, even attracting the same fans, until the climate underwent a sharp change in the ’70s.

The 966-page Rough Guide to England doesn’t find space for even a passing mention of either town

“Before the hooliganism of the 1970s, fans would watch both clubs when they played at home,” says Lee Grooby, who edits Blackburn’s official website. “That doesn’t happen now and the rivalry is a bitter one. Burnley definitely hate us more than we hate them though.”

Games were thus restricted to pre-season fixtures. “The two teams didn’t play each other in the league between 1983 and 2001,” explains Peter Smith, a football journalist raised in East Lancashire. “When the sides met in the 1970s there was carnage because the towns share the same rail line. Fans were ambushed and bricks were thrown at trains.

“Throughout the ’80s the teams met in the pre-season Lancashire Cup. It was a nothing competition, but it meant everything to both clubs. Rather than try players out, managers would play their strongest teams because that’s what the fans demanded. But when Kenny Dalglish took over in 1991, Blackburn withdrew their support – they had bigger ideas.”

Fortified by steel magnate Jack Walker’s millions, Blackburn were about to embark on a run that would eventually see them win the Premiership in 1995. Yet their fans never missed an opportunity to rub Burnley’s noses into the mire.

In 1991, one opportunist hired an aeroplane and trailed the message: ‘U R Stayin down 4 ever, luv Rovers – ha, ha, ha’ over Turf Moor as Burnley struggled to overturn a 2-0 deficit against Torquay United in the second leg of the Fourth Division play-off semi-final. Most Burnley fans think that man was former Blackburn striker Simon Garner, though he denies it in his autobiography.

Nonetheless, Garner’s status as a Blackburn idol means he’s loathed in Burnley anyway. Asked if he’d be attending the first game, Garner replied: “No, I’m not very popular in Burnley.”

Indeed, Garner has never been popular with Burnley fans, not even when he met them on the inside following a 1996 stretch for contempt of court during divorce proceedings. He served his four-week sentence at Kirkham open prison in Lancashire. “It wasn’t far from Blackburn and there was a split in the prison between Blackburn and Burnley fans,” he remembered. “Luckily I had Blackburn fans to look after me… people who the Burnley fans knew were not to be messed with.”

With two hours to kick-off, FourFourTwo leaves the Blackburn fans to their McDonald’s (one local proudly proclaims it the busiest in the country) to seek out Burnley’s side of the story. As we leave, Riley admits a grudging respect, envy even, for their most bitter rivals. “The one thing Burnley have over us is that they’ve retained more of an identity,” he says. “We’ve lost a bit of ours, appealing to Baddiel and Skinner post-Euro 96 type fans. We’re a more family-orientated club and at times that doesn’t make for the best atmosphere inside Ewood. I just wish we had more lads who were more passionate.”

Journalist Peter Smith agrees. “There’s probably more passionate support from Burnley. It’s said in these parts that if Jack Walker had been a Burnley fan then the ground would have been full every week. Blackburn had the best team in the country in 1995 and they still couldn’t fill their ground unless Manchester United visited.”

Ewood Park will be full tonight, there’s no doubt about that, but the increased segregation will limit the attendance to 28,691, including 7,000 Burnley fans in the Darwen End. With Walker’s money, the archetypal northern ground was transformed into a Premiership-class stadium in the 1990s. Surrounded by terraced housing and low-level factories, its brilliant white steelwork (supplied, you’d assume, by Jack’s contacts) dominates the southern end of the town, an incongruous giant spaceship in its retro northern setting.

Three shops face Ewood’s main stand on Manchester Road. One, with 1950s signage, announcing ‘John – Gentlemens (sic) Hair Stylist’. Next door is the equally unpretentious Ewood Cafe. Their neighbour is Star Fruit, which is closed because, as the owners explain with a window sign, they’ve gone to see their granddaughters in New Zealand. There’s a picture of the two children as proof. You probably wouldn’t get that in the chic bistros around Stamford Bridge.

But then, according to some Burnley fans, you wouldn’t get Blackburn supporters like Steve Pickles. Describing himself as a fan that’s “had the chaff not the wheat”, Pickles, 34, is a brewery account manager. He’s suited, articulate and fits his job around attending 60 or so games a year. He’s slightly embarrassed to be watching tonight’s game from an executive box, but even there segregation applies, with corporate Burnley fans escorted to their sumptuous facilities in the Darwen End.

“My daughter, Bethany, is Blackburn,” he confesses, keen to get the subject off his chest. “I forced my ex-missus to have her at Burnley General because I didn’t want ‘Blackburn’ on her birth certificate. Then she turns out to be Blackburn anyway. I’m gutted. I’ve done all I can to change it. She’s been Burnley mascot three times and I even got her a signed Paul Gascoigne Burnley shirt.

"It didn’t work, though, so I have to limit the damage by making sure I give her her pocket money the day after a Blackburn game so she can’t spend it at Ewood. I couldn’t bear to have my money being spent there.

“Blackburn are Johnny Come Latelys, the new money, fur-coat-no-knickers brigade,” he adds. “The number of Rovers fans I speak to who claim that they were going before Walker put his money in means they must have had 100,000 crowds. They’re two-bob millionaires, but they’ve had their day in the sun and it won’t happen again.”

Burnley fans are a different breed, he reasons. “We’re used to being kicked in the balls, Blackburn aren’t. We’ve got no delusions of grandeur because we’re so used to having the stool kicked from beneath us. The defeats create a camaraderie among the fans that’s special. We might watch dross sometimes but we still watch them every week because it’s our team, isn’t it?

“There’s nobody in Burnley who wears anything but a Burnley shirt,” he adds, citing another key difference. “You see Man United and Liverpool shirts in Blackburn. Those people would be chastised in Burnley.”

And what of the pied piper himself, Jack Walker, wonders FourFourTwo...

“A lot of Burnley fans think that Walker was a senile old tosser but I think most fans would love a Jack Walker. He was wasted on them though. His money should have gone into a town where there was passion for the club. If Blackburn had experienced the run we’ve had in the last 10 years they’d be getting 5,000 crowds now.”

Pickles is originally from Accrington. The home of the Stanley lies on the M65 between the two towns; its population was previously split between Burnley or Blackburn, with a few hundred diehards following the miserable fortunes of the local non-league club who lost their league status in 1962.

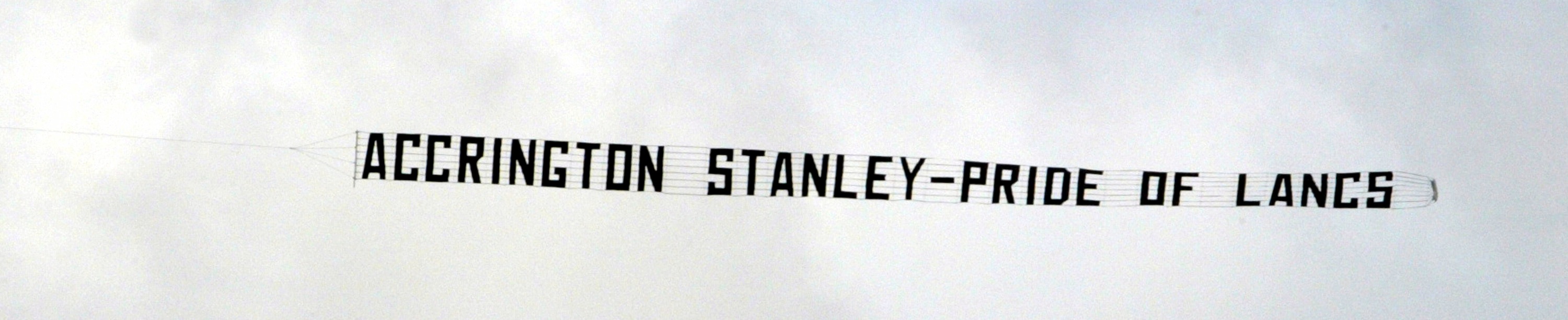

Recently, however, Stanley have progressed to the upper echelons of the Conference, with gates rising to a 1,500 average. Fans of both clubs estimate that Accrington are taking 500 off the gate at Turf Moor and Ewood Park. And, like a contemptuous kid brother, Stanley fans are getting cheeky. They paid for a plane (not an original idea, admittedly) to buzz the Burnley v Blackburn match trailing the message: ‘Accrington Stanley – Pride of Lancashire’.

The Burnley fans arrive in a trail of 80 coaches, parked sardine-close behind the Darwen End. Fans spill off their transport to form a procession which leads to the turnstiles. Spirits are high. They’re singing “No, nay, never”, the song to the tune of the Wild Rover which is popular with both sets of fans. They’re loud and proud, like an army marching into battle against their oldest foes. Adrenaline provides them with overwhelming optimism.

The familiarity level is high with people greeting, nodding and winking. They’re in it together. They aren’t the face-painted clowns picked out by Sky TV cameras before matches: being Burnley is their badge of identity, through thick and thin, for better or worse. A wall of police officers separates them from the Blackburn fans. A helicopter hovers above, its search light occasionally piercing the freezing darkness.

Leading the police operation is Inspector Chris Hayhurst of the East Lancashire Division. “We’ve got a major police operation on tonight,” he explains as he monitors the Burnley fans. “For a large Blackburn game we’d normally have around 150 police, but because of the possibility of disorder and the rivalry and history between the two clubs we’ve got 400 here tonight.

“We’ve identified areas where we think rival fans will try and meet for disorder. Banning orders have been enforced too. We sent letters to all the banned supporters and some of them had personal visits. We’ve had minor incidents of disorder so far.”

Having received information through his earpiece, Hayhurst jumps into a police car which, lights flashing, speeds off to an incident. A total of 40 fans will be arrested for public order offences before the night is out.

A declining breed at smaller clubs, the fanzine seller seems appreciated by the passing Burnley fans. Had it not been closed by police, Martin Barnes, editor of Burnley’s When The Ball Moves fanzine, would have been in the pub with his mates. Instead, he’s left outside shivering as he sells his latest issue. “The rivalry is tribal,” he explains. “They call us Dingles and say we’re from Yorkshire – that shows how good their geography is. I don’t hate Blackburn, but they do deserve our pity.”

The enmity flourished - a game between the two clubs at the end of the 19th century had to be stopped because of crowd violence

Barnes talks openly about the negative headlines Burnley sometimes receives in the national press because of the British National Party’s presence in the town. “Burnley is one of the most economically deprived towns in Britain,” he says. “A lot of industry has left the area and we’ve got a large ethnic minority within the town. The BNP have latched onto certain areas, including Burnley, hoping to get a foothold. For the vast majority of Burnley fans there’s absolutely no issue with racism.”

Steve Pickles agrees. “I go to every game and I’ve never seen a black player abused by our fans. We’ve got Micah Hyde and Frank Sinclair in our team. These players wouldn’t come to Burnley if they felt we were racist.”

Clarets fans have another point of contention they want to clear up. “Rovers claim that the rivalry is one-sided and that they don’t care about us. They claim that they’re rivals with Manchester United,” says one fan filing through the turnstiles. “Why, then, did they sing ‘Are you watching Burn-er-lee?’ whenever they played in Europe? It’s because we do matter.”

After one such European game in 1994, when Swedish part-timers Trelleborgs dumped Blackburn out of the UEFA Cup, one creative individual visited all roads leading to Burnley and erected signs reading, ‘Twin Town: Trelleborgs’.

When Blackburn last entertained Burnley, in 2001, their squad had been on a warm-weather break in Dubai. They won 5-0. Following tradition, Rovers’ players have just returned from another break in the oil state. Burnley’s players visited a local swimming baths.

Inside the ground, everyone is pumped-up for the game. They don’t seem to notice the bitter cold, yet the atmosphere is stifled before kick-off by a public address system pumping out pop music. Ewood Park is often derided for its lack of atmosphere; why Blackburn should choose to muffle it further by music played so loud you could hear it in Burnley is mystifying. Perhaps it’s to drown out the tasteless and offensive songs, of which there are many.

When the music is finally switched off, the game begins. The stadium is bouncing. Both sets of fans are trying to out-shout each other with primal screams of ‘Who the f*cking hell are you?’

Four-times World Superbike Champion Carl Fogarty is sitting in Blackburn’s Main Stand, although there’s no sign of other celebrity Rovers such as Jim Bowen and Wayne Hemingway. One fan sneers dismissively that Burnley’s most famous fan is the bloke who wears a wig on the advert for Safestyle UK windows. He’s obviously not into politics.

With the Blackburn end screaming: “Get into them!” battle commences. The nastiness is soon evident when Burnley fans sing: “Who’s that lying on the carpet, who’s that lying on the floor? It’s Jack Walker on his back and he’s had a heart attack and he won’t be going to Ewood any more”.

Blackburn fans reply as one. “One Jack Walker” they sing of the man who realised their dreams, who enabled them to replace Duncan Shearer with his namesake Alan. Then they get more personal. “Your mum’s your dad; your dad’s your mum. You’re interbred, you Burnley scum”. And again. “Your granddad is your brother, your sister is your mother, you’re shagging one another, the Dingle family”. There’s more: “You’re just a small town in Yorkshire”. Burnley fans parody that one with with: “You’re only here ’cos of Burnley”.

Like the first game, the match is untidy. But at least it has goals. The first of the tie is scored by Blackburn’s Kerimoglu Tugay when his shot is deflected in by Burnley’s Micah Hyde. Fittingly, considering his unfortunate role in the goal, Hyde hits Burnley’s equaliser just before half-time. It’s a moment of genuine quality as he fires a dipping volley over the unsuspecting Brad Friedel.

The Darwen End rises in celebration, but having lost two of their best players to Premiership clubs in recent weeks, a Burnley victory still seems unlikely.

Rovers hero David Dunn, a Blackburn fan from nearby Great Harwood who was transferred to Birmingham City when Graeme Souness was at Ewood, makes the half-time draw. He receives a good reception. You sense he’d be even happier playing tonight.

As the second half ticks away, no more goals are forthcoming and with the game heading for extra-time and the sleet rapidly becoming snow, it’s Blackburn who have the greater urgency against Burnley’s five-man midfield. Neither side deserves to lose, but with four minutes to play Rovers’ Morten Gamst Pedersen hits a cross which rebounds off Frank Sinclair and back into the Norwegian’s path. His shot rockets into the roof of the net and propels his team towards a sixth-round tie against Leicester.

Pedersen will be happy for more than one reason – his former football coach at school in Vadso, a town of 5,000 inside the Arctic Circle, was a Burnley fan.

The home fans milk the remaining four minutes for all they are worth, shouting “Olé” every time a Blackburn player touches the ball. Their more laddish element in the end section of the CIS Stand taunt the away fans, who continue to sing and applaud their vanquished heroes off the field despite defeat.

After the game, Burnley’s colourful manager Steve Cotterill, whose house overlooks one of the pitches at Blackburn’s Brockhall training ground, meets the media. He’s “gutted”, but magnanimous and no doubt cheered by the handy £1 million that Burnley’s Cup run, which included a victory over Liverpool, has earned the club.

“As manager of Burnley Football Club I’d like to wish Blackburn Rovers all the best in the FA Cup,” he says. “And I mean that sincerely.”

Despite their respect for their boss, most Burnley fans wouldn’t agree. And they’ll still be loathing the team they call Bastard Rovers long after Cotterill has retired.

From the May 2005 issue of FourFourTwo.

Andy Mitten is Editor at Large of FourFourTwo, interviewing the likes of Lionel Messi, Eric Cantona, Sir Alex Ferguson and Diego Maradona for the magazine. He also founded and is editor of United We Stand, the Manchester United fanzine, and contributes to a number of publications, including GQ, the BBC and The Athletic.