More Than A Game: How the Mostar derby illustrates Bosnia-Herzegovina's divisions

Mostar: a city divided by religion and politics...

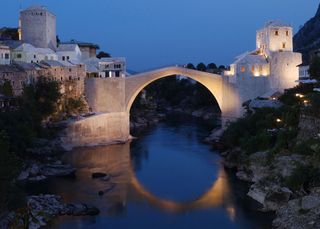

Although few things divide a city like a river, nothing segregates people so completely as a civil war. Mostar is as recognisable for its ethno-cultural partition as it is for the famous Ottoman bridge spanning the Neretva River.

The rupture between the primarily Catholic Croat west bank and the largely Bosniak Muslim east is exemplified by the intensity of the Zrinjski-Velez derby. The animosity between the teams is rooted not only in sectarianism, but also in their divergent political views. More than any other in the Balkans, the Mostar derby is a microcosm of a century or so of Bosnian history, with the clubs defined as much by politics and war as by players or fans.

In 1905, the year of Zrinjski’s foundation, the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires were entering their death throes, heralding the end of their shared dominance of the Balkans. Situated in the middle of the two, Bosnia-Herzegovina had been annexed to Austria-Hungary in 1878 but remained Ottoman in practice until the end of World War I – an event precipitated by the assassination in 1914 of Austro-Hungarian Archduke Franz Ferdinand by Bosnian-Serb Gavrilo Princip in Sarajevo.

Nationalism had been on the rise for a while, particularly among Croats and Serbs, resulting in the proliferation of ‘cultural societies’, which were formed to spread each ethnic group’s separatist message. It was from ‘Hrvoje’, one of these societies, that Zrinjski emerged.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Separatist nationalists v left-wing anti-monarchists

Zrinjski’s existence has forever been linked with Croat nationalism. Its name is a reference to the Zrinski family, the most celebrated of whom was Nikola Subic Zrinski, a Croatian ban [viceroy] who died defending his country from Ottoman sultan Suleiman.

Bosnian social commentator Miljenko Jergovic wrote that an opera about Zrinski’s life even attracted a football-style audience in post-WWII Yugoslavia: “The premiere passed without problems, as did the second, third and tenth showings, before masses of fans began coming to see Zrinski. The first to appear were young men who clapped and cheered the protagonist through his heroic exploits, something which greatly worried the militia…

"However, after some time, an enemy appeared from a different direction. These young men, who were indistinguishable from the first [group], began to cheer the main villains of the opera, namely the Turks, thus angering the first [group of] young men, who responded by yelling, clapping and crying all the more loudly when Zrinski appeared. These events were repeated for a few shows before the opera was removed from the schedule.”

The early days of Velez reflect an entirely different cultural awakening. Early in the 20th century, socialism and communism had presented themselves as an alternative in predominantly monarchist/imperial Europe; given the Balkans' proximity to Russian/Soviet influence, left-wing politics inevitably rose to prominence.

By the end of the 1910s, Mostar’s working classes had started to form their own football clubs, such as Omladina and Zeljeznicar (not to be confused with the Sarajevo club of the same name). These teams were founded on principles different to those based around cultural societies or the mahala [old Ottoman districts]. The focus of these new clubs was inclusiveness and the representation of the working class, regardless of ethnicity.

In 1921, having recognised a threat to the monarchy, King Aleksandar Karadjordjevic of the proto-Yugoslav Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes tried to put an end to communism, leading to the dissolution of Omladina and Zeljeznicar. But a year or so later, a mixed-ethnic group of men established Velez at Omladina’s Sjeverni Logor ground. The club was soon taken over by the local Communist Party, with local party head honcho Savo Neimarovic installed as club secretary. For their crest, Velez chose a red star.

Hijackings and 'hibernations'

Come the first Zrinjski-Velez derby in the early 1920s, the incompatible identities of the two rivals had been instituted. Yet the two clubs have shared a vulnerability to the whim of the authorities; their respective bans and periods of non-existence help define their identities, their recurrent dunking and resurfacing an illustration of the region’s political flux. Each new government’s propensity for picking on whichever team didn’t fit their ideology is part of what defines each club.

Velez’s first ‘hibernation’ was a result of Karadjordjevic’s 1929 ‘January 6th dictatorship’, which abolished the country’s constitution, effectively making him a dictator. Political dissent became near-impossible, meaning that many associated with Velez ended up in prison or ‘indisposed’, paralysing the club. Only in 1936, two years after Karadjordjevic’s assassination in Marseille, did Velez re-emerge.

Another side-effect of the dictatorship led indirectly to the much more lasting disappearance of Zrinjski: the establishment of Croat nationalist group, the Ustasa. Set up by activists exiled by the king’s abolition of nationalist parties (the group later played a part in Karadjordjevic’s assassination), in WWII the movement was the power behind the short-lived Independent State of Croatia (NDH), a puppet of Mussolini’s Italy and Nazi Germany that annexed Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and parts of Serbia. Fervent Catholics and extremely right-wing, Ustasa helped turn Croatia from Yugoslav province to fascist state.

Zrinjski, as symbol of Croat nationalism, became part of the NDH football league. Upon the formation of the new, communist Yugoslavia in 1945, this caused the club to be stigmatised by the party leadership. Zrinjski’s emblematic nature and favour under the NDH made them a distasteful reminder to those driving Yugoslavia’s left-wing resurgence. Come the war’s end, Zrinjski ceased to be, their archives destroyed and their memory left to wane over time.

Velez, on the other hand, did not prosper during WWII. The birth of the NDH saw the club forced once more into whichever abyss it is that Balkan clubs tend to disappear. After a friendly game turned into an anti-fascist rally, the Mostar authorities responded ruthlessly. Against the background of a general strike, police reprisals and demonstrations, Velez slipped not-so-quietly out of sight.

Long-time member Mesak Cumurija hid the club’s archives and trophies, the secret location of which was lost upon his arrest and subsequent death in Sarajevo. Many associated with the club ended up in a nearby concentration camp at Lepoglava; more than 80 Velez players and functionaries are believed to have died in WWII, either in the camps or fighting alongside Tito’s communist Partisans.

Clubs at war – literally

During this period, supporters and affiliates of Velez and Zrinjski were literally on the opposing sides of a war – and not for the last time, either. But unlike Zrinjski, the post-war years proved a renaissance for Velez. Within 10 days of the war’s conclusion, the Communist Party restarted sporting activity in Mostar, re-forming Velez in the process. By the mid-1950s, the club was competing in the top division of the united Yugoslavian league.

There was to be another twist in the tale, when in 1992 war returned to Mostar. The city, brought to a standstill by shelling and sniper fire, was gradually split into separate, ethnically distinct parts loosely based around the frontline, taking the Neretva’s natural border into account – Croats in the west, Bosniaks in the east. Most of Mostar’s Serb community were forced to leave the city during the war. Although pockets of people remain on the ‘wrong’ side, Mostar was to all intents and purposes torn in two by the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s.

As is often the case, the spoils of war were not evenly distributed. Despite initially fighting alongside Bosnian-Muslim forces (ARBiH) against the Serb-led Yugoslav People’s Army, the HVO (Croatian Defence Council) wound up in direct conflict with the Bosniaks after the Serbs’ defeat and retreat. Soon, the HVO were in control of west Mostar, where the ARBiH had previously been headquartered. A series of official acts issued by the HVO seized a vast swathe of property in the west, including Velez’s Bijeli Brijeg stadium, assets and equipment. In an echo of Zrinjski’s dissolution, Velez were essentially mandated out of existence by the Croat administration in Herzegovina.

They wouldn’t reappear until 1994, when the search began for new players and equipment. With the war ongoing, many of those involved were still on active duty. They were assisted by donations from abroad, particularly from the Bosnian diaspora in western Europe. The derby, however, had to wait, as Bosnia’s separate Bosniak and Croat leagues weren’t merged until 2000 (with clubs from Bosnia-Herzegovina’s Serb province Republika Srpska joining in 2002), allowing Velez and Zrinjski to contest their first derby since 1938.

NEXT: A shift toward Islam

Velez and Zrinjski in the modern era

Having been outlawed for 47 years, Zrinjski re-formed the same year the HVO took control of west Mostar. They ‘inherited’ the Bijeli Brijeg stadium from Velez. Born of a separatist movement and banned by a federalist, multi-national state before a rebirth that capitalised on a wave of nationalism, twice Zrinjski have come to represent the Croat desire to step out from the shadow of a much larger authority, albeit in different circumstances.

Regardless of political outlook, this is something that resounds with many Croats, most of whom understand what it means to be part of a secession movement, whether from Austria-Hungary, Karadjordjevic’s Yugoslavia, the NDH, or socialist Yugoslavia. Having always been part of a bigger whole, Croats have struggled for a collective identity, and Zrinjski represents in part that longing to have something of their own.

More difficult to quantify is the identity of Velež today. The sectarianism of modern Mostar leaves the club’s left-leaning, non-denominational nature in doubt. Some deny that Velez is now the preserve of a single community, maintaining that the club still upholds the socialist Yugoslav principle, but this is probably mere idealism. Given most Serbs left Mostar at the start of the war, and that the majority of Mostar’s Croat fans support Zrinjski, Velez – with its location now in a distant outskirt of east Mostar – has been left with a mostly Muslim fan-base.

“Older people like to say how nothing is the same anymore – and I’m afraid to say they are right,” says journalist and Velez fan Sasa Ibrulj. “However, I wouldn’t say that Velez’s identity is completely lost, especially in comparison with the situation at other clubs or the fan movement of Yugoslavia. Velez is still the closest club to the ‘left wing’ movement, which has almost ceased to exist in Bosnia-Herzegovina, and is one of the rare clubs that identifies itself with the anti-fascist movement, and on whose stands you can see images of Tito and Che.

“When it comes to the national make-up of supporters, it is clear this is something that has changed, but I think that is a logical consequence of war. Over a third of the city’s population left Mostar during the 1990s, and this has obviously influenced the fanbases. It is a fact that the city is divided and that Velez exists and functions in the Bosniak-dominated part, so I think it is logical that most of its fans are Bosniaks. However, I do not consider Velez to be an exclusively Bosniak club, and I stand firmly against labelling Velez as anything other than Mostar- and football-oriented.”

A shift toward the Muslims

Correctly or incorrectly, though, Velez have become a device through which Mostar’s Bosniaks find a counter-balance to the explicit identity of Zrinjski. This is common in Bosnia-Herzegovina, where elements of each demographic express themselves through football, whether by supporting Borac Banja Luka in the capital of Republika Srpska, Zeljeznicar in Sarajevo, Zrinjski or Velez.

Velež’s tacit shift towards the Muslim community, and Zrinjski’s long-standing connection to the Croat community, is represented by the makeup of their respective youth teams. “Something I always bring up as an example of the city divide is the youth category,” says Ibrulj. “The junior divisions are, almost without exception, single-national, simply because Croats live near Zrinjski and Bosniaks near Velez. Of course there are exceptions, but they merely serve to prove the rule.”

For Ibrulj, another important influence on modern Velez was the collapse of the Yugoslav political system and the subsequent effect of the city’s politics on the club: “A large number of people are not happy and are nostalgic for the better times. As a typical victim of, firstly, the war, and then the transition period that almost destroyed the club, Velez is part of that nostalgia – not just in Mostar but throughout the former Yugoslavia.

Mostar is a slave to politics. This is the way of things throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina; politics uses sport for all it can get

“Velez’s connection with socialism in Mostar cannot go away, as there are still those among the fans who are left-oriented, and I believe that the fans and the club will always be proud of what was achieved during socialism. However, a group of people that small cannot change society and Velez is just a small part of everything that has been happening.

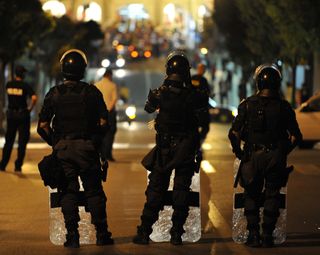

“Mostar is a slave to politics, which dominates the utility and emergency services, nurseries and, of course, the football clubs. Through Velez and Zrinjski the parties can influence everyday happenings and influence supporters in order to collect votes. Unfortunately, this is the way of things throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina; politics uses sport for all it can get.”

Rarely does the path of a single club, let alone both sides of a derby, so poignantly correspond with the zeitgeist of a city and its constituents. The two teams’ histories and identities are so wildly different, forging a relationship between both sets of fans steeped in mistrust and polarity. However, the Mostar derby is more than a mere case of ‘us’ versus ‘them’. There are added dimensions that set it apart from other derbies: geo-political history, ideology, profiteering, circumstance and war.

Fans of both teams might object, but it is to a certain extent politics played out on the pitch. It’s a clash that deserves recognition as something more than a quaint Balkan curiosity or another far-flung derby to titillate western fans. The truth is it’s much more than that.

'When PSG went 1-0 up against Liverpool, all of a sudden I started getting abused. At the end of the game, I felt like I grew 10 feet walking around Anfield!': Manchester United legend reveals sitting in home end of Champions League clash

'It’s unacceptable for Arsenal to be making the same mistakes year-after-year with the same manager': Gunners legend makes huge Mikel Arteta claim after Premier League failings