Narcos: When Pablo Escobar did football – and changed the game in Colombia forever

Pablo Escobar may be one of history’s most infamous criminals, but he also had a soft spot for football. Here's the story of how his passion – and money – changed the face of Colombia's game

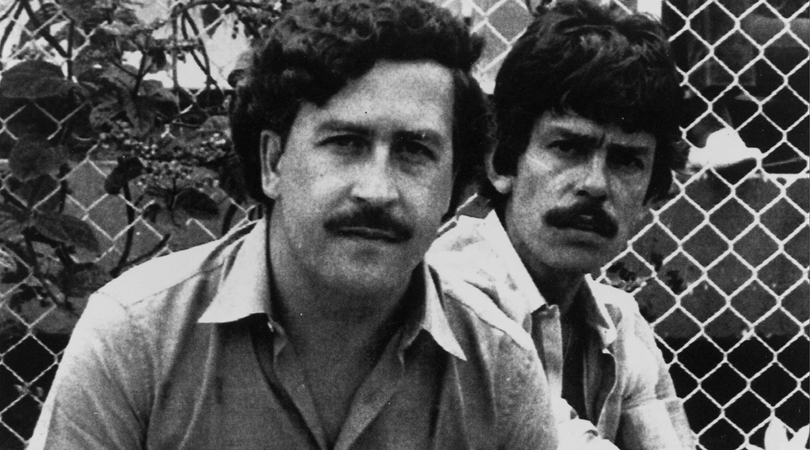

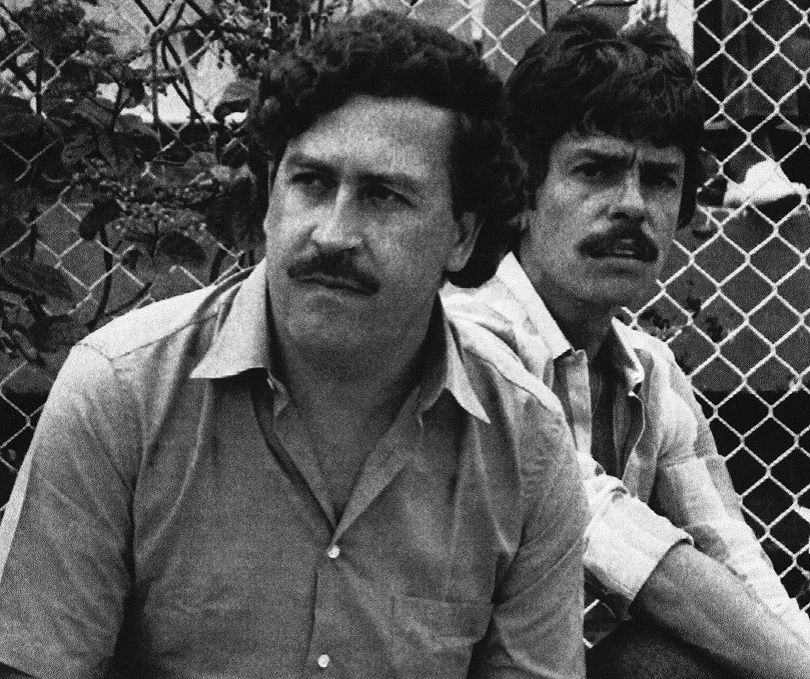

The reputation and legacy of Pablo Escobar, the Colombian drug trafficker who became the wealthiest criminal in history, is a messy knot to untangle.

As Netflix viewers worldwide gorge on his bloody journey via the superlative Narcos, passing the popcorn as he blows up planes, assassinates ministers and builds his own zoo, the people of Colombia who lived through his very real mayhem remain conflicted.

Escobar was many things: a murderer, briber, bomber and racketeer, according to his mile-long rap sheet. But to some, he remains an unlikely saint. A huge Escobar flag still marks the entrance of the barrio he built on the site of a former rubbish dump in order to house the poor. On the roadsides of his home city, Medellin, salesmen hawking car stickers – Jesus, Hello Kitty, The Simpsons – report that ‘Pablito’ remains their top seller. There’s even an Escobar children’s sticker album.

Football influence

Pablo played, watched and discussed the game at every opportunity – but he also became the shadowy figure behind the incredible rise and fall of the Colombian game between the mid-’80s and USA 94

Others cannot hide their disgust. Rodrigo Lara Restrepo, son of assassinated Justice Minister Lara Bonilla, says that selling Escobar imagery is “an example of the triumph of the culture he embodied... profit is more important than anything”. For many, this man destroyed their land. But for all, their country’s recent history is inseparable from El Patron. His influence on the underworld, the government and the police is obvious. Less well-known is how far his tentacles extended into the world of football.

Pablo played, watched and discussed the game at every opportunity – but he also became the shadowy figure behind the incredible rise and fall of the Colombian game between the mid-’80s and USA 94. “Pablo always loved soccer,” says his sister, Luz Maria, in The Two Escobars, the superb ESPN documentary about his life and that of murdered player namesake Andres, whose story is intertwined with Pablo’s. “His first shoes were football boots. And he died in football boots.”

This is what happened in between.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Awash with cash

While wads were splashed on cars, ranches and other indulgences, many attested to Escobar having a genuine social conscience, determined to use his wealth to help those in need

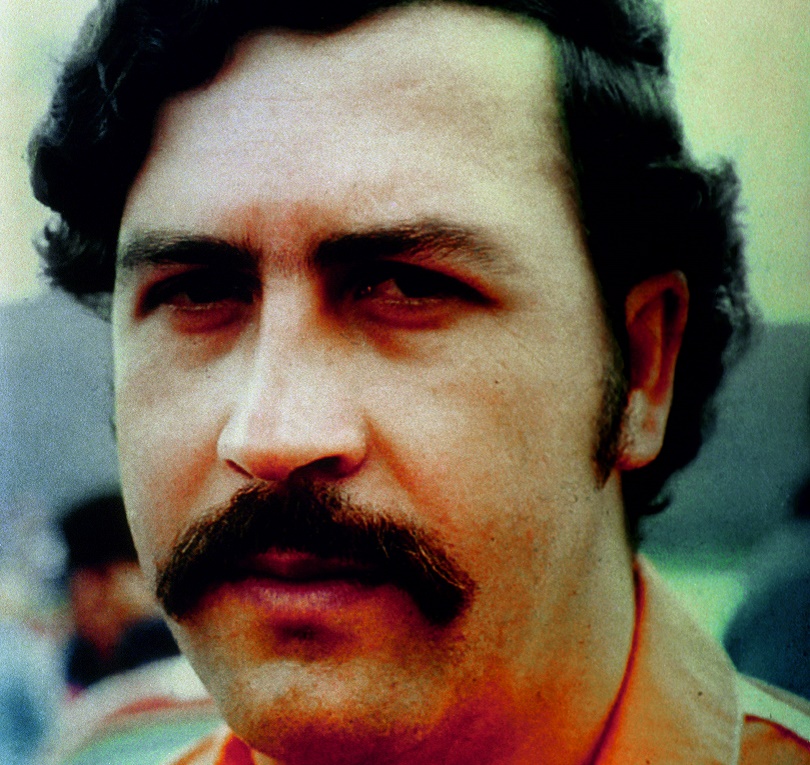

Familiarity with Pablo’s story hasn’t dimmed its power to astonish. One of seven children born to a farmer and a schoolteacher, he had a far from deprived childhood, but his ruthlessness was evident early. While committing petty crimes with his brother, Roberto, he schemed about how they could make some real money.

Early involvement in a kidnapping – Pablo netted $100,000 from the ransom – showed that he had the stomach to do whatever was necessary. And in the mid-1970s, the brothers realised that smuggling was their best bet.

A simple eureka moment, in which Escobar recognised the growing popularity of cocaine and the relative ease of flying it into Florida, would lead to a fortune eventually estimated at $50bn. At his zenith, Escobar was supplying 80 per cent of America’s coke. His equally simple strategy for getting away with it – “silver or lead” – saw him bribe willing officials and murder those who couldn’t be bought.

But Pablo had a problem: too much cash. With the government and the USA monitoring his activities, tons of notes were buried in the countryside. And while wads were splashed on cars, ranches and other indulgences, many attested to Escobar having a genuine social conscience, determined to use his wealth to help those in need. As he built houses and schools in impoverished communities, he won a reputation as a latter-day Robin Hood. His favourite act of benevolence was creating football pitches in the slums. “He focused on generosity in the community,” says Luz Maria. “In our neighbourhood, Pablo donated floodlights and football supplies.”

'Laundering heaven'

With turnstiles taking cash, they could easily declare far higher earnings than were made, often by a million dollars or more, and immediately ‘clean’ the drug money

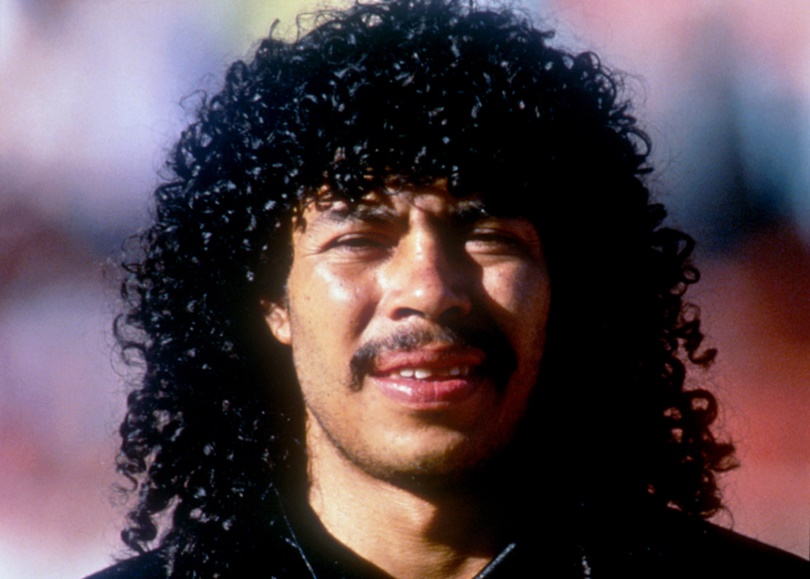

Pablo was always a keen player. Right-footed, he liked to operate on the left wing and cut inside (imagine Craig Bellamy with a dodgy ’tache). He wasn’t an athlete, but he loved to mix with genuine contenders. His pitch projects led to an early friendship with many players who went on to become professionals. “There were tournaments in the slums,” recalls Chonto Herrera, who later turned out 61 times for Colombia. “Whole communities forgot their worries. I was very poor, but on the field we were important, and lived in a perfect world.”

Alexis Garcia, Chicho Serna, Rene Higuita and Pacho Maturana were among the future internationals who developed on Pablo’s pitches, and often watched in admiration as he opened them, making speeches as if he was a benevolent mayor. “Everyone talked about who donated the field, and he was criticised for being a drug lord,” says Leonel Alvarez, who won 101 Cafeteros caps. “But we just felt lucky to be given pitches.”

Football also provided a darker benefit for Pablo. His brother Roberto – AKA The Accountant – wanted to legitimise their loot. A club was perfect. With turnstiles taking cash, they could easily declare far higher earnings than were made, often by a million dollars or more, and immediately ‘clean’ the drug money. A similar trick could be turned with player transfers. The sport was a laundering heaven.

Team-building

"The introduction of drug money into soccer allowed us to bring in great foreign players,” says Maturana, Nacional manager from 1987 to 1990

It was also a chance for Escobar to play God at his hometown clubs. Just as he was starting his empire in 1973, Medellin’s Atletico Nacional were winning Colombia’s top flight for only the second time in their history. By the ’80s, with millions rolling in, it was decided: Pablo would fund the team further, and turn them into one of the best sides in South America.

He wasn’t brazen – or dumb – enough to appoint himself director or owner, but his involvement became an open secret. “The introduction of drug money into soccer allowed us to bring in great foreign players,” says Maturana, Nacional manager from 1987 to 1990, in The Two Escobars. “It also kept our best players from leaving. Our level of play took off. People saw our situation and said Pablo was involved. But they couldn’t prove it.”

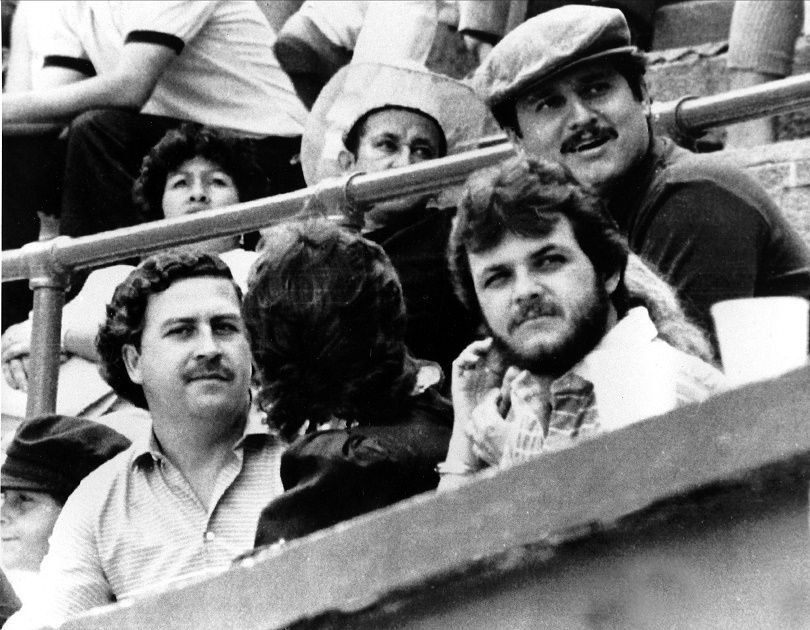

Escobar also invested in Nacional’s city rivals, Deportivo Independiente Medellin (DIM), and was regularly in the stands for games at their shared Estadio Atanasio Girardot. The budget bonanzas were mirrored elsewhere, too, as fellow drug lords saw the value. Pablo’s associate Jose Gacha (‘El Mexicano’) ploughed funds into the Bogota-based Millonarios, while Escobar’s rival Miguel Rodriguez Orejuela, head of the Cali cartel, bankrolled America de Cali. ‘Narco-football’ had arrived.

Continental kings

After all, on the pitch, Maturana’s Nacional were on the verge of something big: they were looking to become the first Colombian side to lift the Copa Libertadores

Now the big cheese at the Medellin clubs, Pablo took the concept of fantasy football to a whole new level. He’d regularly stage private matches at his home against an XI picked by El Mexicano. “The games were a friendly rivalry,” says Pablo’s cousin Jaime Gaviria. “Pablo would say: ‘Pick your dream team – we’ll fly them to the ranch and bet.’” Players were generously compensated, and the cartels would often wager a million or more on the outcome. Some players, such as Nacional’s Andres Escobar (no relation), were said to be uncomfortable about having to perform for the traffickers – and with the source of their wages. Most were happy not to think about it too deeply.

After all, on the pitch, Maturana’s Nacional were on the verge of something big: they were looking to become the first Colombian side to lift the Copa Libertadores. In 1989, they were drawn in the same group as Millonarios. El Mexicano’s Bogota outfit topped the group after a 2-0 victory at Nacional, but both sides progressed to the knockouts. Nacional then beat Argentina’s Racing Club and Millonarios overcame Bolivia’s Bolivar, only for the Colombians to be drawn against each other in the quarters. This time Nacional had the upper hand, and scraped through 2-1 on aggregate. A 6-0 thrashing of Uruguay’s Danubio set up a final with Olimpia of Paraguay. After a 2-0 defeat in Asuncion, Pablo took his place in the stands for a tense return leg – but in Bogota, with Nacional’s stadium deemed too small.

With Andres Escobar anchoring the defence and flying goalkeeper Rene Higuita performing heroics, an own goal and a strike from Albeiro Usuriaga levelled the tie on aggregate, taking the game to penalties. “This is a moment for the history books,” gushed the Colombian commentator, a nation hanging on his words.

Andres Escobar slotted home Nacional’s first, and Higuita made athletic stops and converted his own spot-kick to take the shootout into sudden death, but their team-mates wasted chances to seal the title. “I told them: stop short, because their keeper is diving early,” said Maturana. “But no one listened… except Leonel.” Following three missed opportunities for his side, Leonel Alvarez paused, read the dive, and pumped home the crucial penalty.

Nacional win the Libertadores

Growth of the game

Colombia suddenly had a true source of pride: football, which was thanks in no small part to the drug lords

It was a moment of euphoria. “Pablo jumped and screamed with every goal,” says Jhon Jairo Velasquez Vasquez, AKA Popeye, an Escobar henchman who committed more than 200 murders for the cartel. “I’d never seen him so euphoric. Normally he was a block of ice.”

Nacional’s players were summoned to Escobar’s ranch for a giant party. “They came for their bonuses; Pablo even raffled off a truck,” says Jaime Gaviria. “For Pablo, the players weren’t commodities, they were friends. It went beyond money. He wanted them to be happy.” As national team coach, Maturana started to steer a squad including several Nacional players toward USA 94.

Colombia suddenly had a true source of pride: football, which was thanks in no small part to the drug lords. But there was a sinister side already in evidence. At a November 1989 match between Escobar-backed DIM and Miguel Rodriguez’s hated America de Cali, rumours circulated that referee Alvaro Ortega had been bought off. “The ref blatantly robbed us,” says Popeye. “Pablo told us to find him and kill him.” Ortega was gunned down shortly afterwards.

Footballers in Colombia soon realised the downside of the narco millions. “When I was going back home after the game, I heard the referee was killed,” says Oscar Pareja, a midfielder for DIM. “We were numb. We knew there was a lot going on with the owners; that they were very shady. But when you’re a footballer, you don’t know too much.”

Chaotic Colombia

In 1989 Escobar’s men killed Galan, as well as blowing up a jet with more than 100 passengers (mistakenly believing Galan’s successor, Cesar Gaviria, was on board) and truck-bombing the Colombian security service’s HQ

Away from cup-winning glory, 1989 had been an extraordinarily bloody year for Escobar. His biggest fear had always been extradition to the USA. To get immunity, he’d gained election to the chamber of representatives in 1982, propelled by working-class support. His status, however, had been overruled by the crusading of the Minister of Justice, Lara Bonilla. Escobar had Bonilla assassinated.

A wave of anger followed, and Liberal Party candidate Luis Carlos Galan gained popularity thanks to his anti-cartel platform. But in 1989 Escobar’s men killed Galan, as well as blowing up a jet with more than 100 passengers (mistakenly believing Galan’s successor, Cesar Gaviria, was on board) and truck-bombing the Colombian security service’s HQ. Eventually, Gaviria was elected president, vowing to dismantle the crime syndicate of “a deranged leader”.

While Colombia’s streets descended into Government vs Cartel mayhem, the national team lost just one game in 34 in the years building up to the 1994 World Cup. And in 1991, after extradition was abolished, Pablo handed himself in – on the condition he could build his own prison, La Catedral, complete with a football pitch. Colombia’s international players – celebrities due to their hot streak – were among his visitors, playing games against the prisoner and his ‘guards’, even in the middle of a season. “Coach said practice was cancelled,” recalls Pareja. “What else could he do? He [Escobar] talked about football – he knew everything. He said to me: ‘Why do you yell at the refs so much? We pay them.’”

Guest of honour

We met in an office and he said he loved my game and that he identified with me, because, like him, I’d triumphed through poverty

In 1991, a go-between approached Diego Maradona, saying only that a very important person in Colombia wanted to pay him “an enormous fee” to play a friendly alongside the likes of Rene Higuita. “I was taken to a prison surrounded by thousands of guards,” claimed Maradona recently. “I said: ‘What the f**k is going on? Am I being arrested?!’ The place was like a luxury hotel. They said: ‘Diego, this is El Patron’. I didn’t read the newspaper or watch television, so I had no idea who he was! We met in an office and he said he loved my game and that he identified with me, because, like him, I’d triumphed through poverty.

“We played the game and everyone enjoyed themselves. Later that evening, we had a party with the best girls I’ve ever seen in my life. And it was in a prison! I couldn’t believe it. The next morning, he paid me and said goodbye.”

Pretty much the entire Colombia squad went to La Catedral, it later emerged, often covered up with towels over their heads on the road in there – but one of them didn’t get away with it. Higuita, the 5ft 9in sweeper-keeper nicknamed El Loco, made the mistake of speaking to reporters en route. A national outcry resulted. How could Colombia’s pride and joy associate with a criminal?

Higuita was imprisoned in 1993, supposedly for acting as an accomplice in a kidnapping, but, according to The Two Escobars, his association with the cartel was the true reason behind his arrest. “All they asked me about was Pablo,” he recalls of his interrogation. “He has always taken care of the poor: he built homes and pitches. But he is also responsible for an awful war. I had an opportunity to thank him personally for handing himself in. I did not think I was breaking the law.” Coach Maturana defended his player, saying: “If Don Corleone invites me to dinner, I show up.” But Higuita would miss the World Cup in the USA as a result.

No World Cup dream

But he would not live to see his country play in the USA: in December 1993, Escobar was shot dead by Colombian police on a Medellin rooftop

Pablo had bigger problems. Murders were committed inside La Catedral, and under intense pressure, the Government concluded that he needed to be ‘properly’ imprisoned. Escobar went on the run.

Even in the gravest danger, football remained on Pablo’s mind. His only break from waging war was to watch matches. Popeye recalled the pair hiding in a ditch, pursued by government soldiers, while Escobar listened to a World Cup qualifier on a tiny radio. “I could sense troops closing in, and I’m freaking out. Pablo turns to me and says: ‘Popeye!’ I think they’ve caught us, and I cock my M16, but he says: ‘Colombia scored a goal!’ Football was his joy; his escape; his cloud nine.”

But he would not live to see his country play in the USA: in December 1993, Escobar was shot dead by Colombian police on a Medellin rooftop. He was wearing football boots. His passing left a void that was filled by bloody feuding among the cartels. Football, as ever, was affected. During USA 94, Chonto Herrera’s brother was killed in a car crash. Barrabas Gomez, brother of assistant coach Hernan, left the squad after death threats demanded he didn’t play. And then young Nacional defender Andres Escobar, whose own goal against the hosts helped to eliminate the side from the tournament, was gunned down after a dispute with gangsters. “None of it would have happened under Pablo,” claims his cousin, Gaviria. “He had rules.”

Andres Escobar's fateful own goal

Colombia’s golden era of football was over before it had begun. Informed that their lives were in danger, numerous high-profile players decided to opt out of playing for the national side. Criminal involvement was weeded out of the sport, and the cashflow into the domestic game dried up. Colombia dropped from 4th to 34th in the FIFA rankings over the next three years. Deprived of their key financier, it took Nacional 11 years to win another league title, while a Colombian side didn’t lift the Copa Libertadores again until Once Caldas in 2004.

Not completely clean

“One must attribute Colombia’s rise to the influence of drug money,” says Juan Jose Bellini, President of the Colombian FA. “We all allowed it. We all participated.” Bellini himself was later convicted of money laundering. Andres Escobar’s death, a watershed tragedy, was seen as the ultimate result of a violent storm initially unleashed by his namesake.

Whether ‘narco-football’ truly died with Pablo Escobar, though, is questionable. In 2007, Colombian magazine Semana intercepted a telephone call from feared paramilitary leader ‘Jorge 40’ to a director of Valledupar FC, offering players “who have a certain gratitude towards me” to the club on loan from America de Cali. Another trafficker known only as ‘Macaco’ allegedly controls Pereira FC and attempted to buy El Mexicano’s old outfit, Millonarios. Few doubt that drug profits are still lurking; it’s just not quite as brazen as it was under Escobar.

Maturana admits that as long as there are people willing to take blood money, the problem will continue to eat away at Colombia’s soul. “We exchanged winning for our safety,” he despairs. “Our society was built on a defective foundation.”

This feature originally appeared in the January 2016 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe!

Other stuff you'd like

LIST 9 times clubs really regretted letting a star join a rival

LONG READ Ronaldinho – How the godfather of flair changed football forever

LIST 9 footballers’ brothers who were only signed to keep their siblings sweet (probably)

Nick Moore is a freelance journalist based on the Isle of Skye, Scotland. He wrote his first FourFourTwo feature in 2001 about Gerard Houllier's cup-treble-winning Liverpool side, and has continued to ink his witty words for the mag ever since. Nick has produced FFT's 'Ask A Silly Question' interview for 16 years, once getting Peter Crouch to confess that he dreams about being a dwarf.