Why the real history behind The English Game matters – and what it tells us about modern football

The long-forgotten Blackburn Olympic's achievements are fictionalised in Netflix's The English Game – but the real story is important to know

The English Game, the new Netflix show from Downton Abbey creator Julian Fellowes, has landed at an opportune time. The show examines the early history of football in England and the class element of the game's progression, as a sport with rules laid down by the upper class became increasingly popular with the working class.

It was also a time where the topic of whether footballers should be paid was a genuinely controversial topic. As players' wages becomes a genuine bone of contention in a way not really seen since the lifting of the wage cap 50 years ago, Netflix must be pleased with the coincidental relevance.

WHAT TO WATCH The best football films and documentaries to watch on Amazon Prime

The final episode of the series culminates with the 1883 FA Cup Final – although events are re-arranged for the show's narrative.

So what about the real story of Blackburn Olympic? And why was that final so important?

Blackburn’s football history is a little less celebrated than many other places, but the town has had an important role in both the development and the export of the game, and many clues of that remain. Dynamo Kiev, the most successful club in Ukraine and the former Soviet Union, still play in blue and white because it was founded by a Blackburn Rovers fan. Grasshopper Zürich, the most successful club in Switzerland, still play in what is essentially a Rovers kit for the same reason.

In Spain, Athletic Bilbao and Atletico Madrid both only lost their Rovers-inspired blue and white halves when the person they sent to England to pick up more Blackburn shirts for each club returned with Southampton kits instead (so the story goes, anyway). Atletico retain the blue shorts from the original kit to this day.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

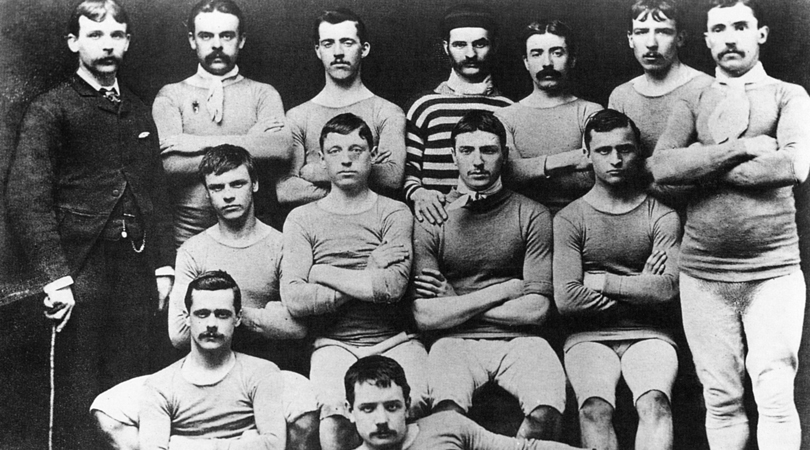

But global Blackburn couture isn’t the only thing the town gave to the beautiful game. More important is the FA Cup final of 1883, where the now-defunct team Blackburn Olympic beat the Old Etonians to become the first northern football club to win the competition, the first working-class club to win the competition and — most importantly — the first team to win the cup by employing a revolutionary new tactic. It was called “passing”. You may have heard of it.

In David Goldblatt’s comprehensive history of the game, The Ball Is Round, he writes that Olympic and “other working-class teams of the Lancashire cotton belt were associated with the ‘alternation of long passing and vigorous rushes’” — essentially a rudimentary counter-attack — while Old Etonians’ cup final victory over Blackburn Rovers in 1882 was “the last in which a predominantly dribbling side beat a predominantly passing side”.

The turning point that the 1883 final proved to be only a year later should not be understated. It gets its own match report in The Ball Is Round, and makes up the first chapter of former Scottish Labour leader Jim Murphy’s 10 Football Matches That Changed The World. In Jonathan Wilson’s history of football tactics, Inverting The Pyramid, he writes that the match was “the final flourish of the dribbling game” as it was superseded by passing.

Olympic were not the first to use passing — as well as fellow Lancastrian teams, Queen’s Park in Scotland were probably the foremost passing side — but they were the first in England to see real success by employing it as a tactic. Taking on a generally fitter, upper-class side who employed a basic ‘kick-and-rush’ approach, Olympic players would knock the ball past their opponents to teammates who had more space, tiring the other team out: Wilson says that the Old Etonians were “unfamiliar” and unable to cope with Olympic’s approach of “hitting long, sweeping passes from wing to wing”. They won with a goal deep in extra time, after a ball from the right flank found Jimmy Costley in space on the left. It was not passing for beauty’s sake, but for winning’s. The Old Etonians were not outfought by their class inferiors, but outthought.

This, too, is political. To dare not to play the proper Etonian way was essentially a class rebellion. The Old Etonians looked down on passing as ungentlemanly and against the spirit of the game. The way they played was likely not that different from how the uncultured Eton wall game looks: a sport in which decades literally go by without a point being scored.

Olympic, an XI of cotton weavers and plumbers, played as a team. Nothing could be achieved without the solidarity of the block. It rejected moments of individual brilliance in favour of collective action. Upon returning to Blackburn, the side was greeted with street celebrations and brass bands.

That match set a template for the game. It showed what could be achieved against the odds by the deployment of passing football. It caught on: the cup returned to Blackburn in the following three seasons, as Rovers became the only ever side to win the FA Cup three times in a row between 1884 and 1886, playing passing football. As the game was exported around the world over the following decades – including, as mentioned, by the blue-and-white clad Blackburnians – it did so with this new style of playing. The pass had won.

The omission of Olympic from any sort of common knowledge is also political. The club has not existed for over 100 years – the FA opted to only allow a single team from any town to join the inaugural Football League, and Rovers’ subsequent success meant that they were invited, and Olympic went bust – so it is easy to explain away why no one has heard of them.

Today, few people know what role Olympic played in the shaping of modern football. Even in the town itself, the side is remembered less than it ought to be. Their old ground, at Hole I’th Wall, now has a sixth form standing on the site. Thousands have played football on its enormous playing fields out back without knowing its significance.

Playing on the same turf without knowing what Olympic did there. Without knowing that this was not, technically, where the pass was born, but where the foundations for the modern game won out.

The erasure of working-class achievement from our shared, everyday knowledge is always political. While Blackburn Olympic’s story remains in the history books, it is absent from our common consciousness. The elision of working-class innovation from our understanding of progress is an old problem – it is why Manchester’s People’s History Museum is so important – but when it comes to the working person’s game, it feels even worse.

While you're here, why not take advantage of our brilliant new subscribers' offer? Get 5 copies of the world's greatest football magazine for just £5 – the game's greatest stories and finest journalism direct to your door for less than the cost of a London pint. Cheers!

NOW READ...

SCOTLAND How Graeme Souness kick-started a Rangers revolution

QUIZ Can you name the 58 players to score 30+ Premier League goals during the 1990s?

DEAL Three ways to (safely) get FourFourTwo magazine right now – with special offers

Conor Pope is the former Online Editor of FourFourTwo, overseeing all digital content. He plays football regularly, and has a large, discerning and ever-growing collection of football shirts from around the world.

He supports Blackburn Rovers and holds a season ticket with south London non-league side Dulwich Hamlet. His main football passions include Tugay, the San Siro and only using a winter ball when it snows.