Newcastle can never succeed with Mike Ashley's identity-draining ownership

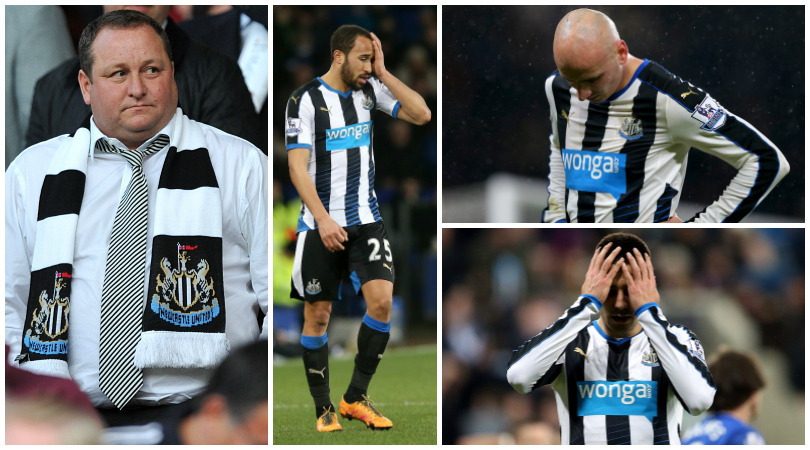

The Magpies could be drifting towards a second relegation to the Championship in seven years. Alex Hess explains why all of the club's problems can be traced back to the boardroom...

It’s fast becoming a staple part of the weekly routine, like the Sunday morning lie-in or fish and chips on a Friday. Every Saturday night, Match of the Day’s cameras will cut from highlights of Newcastle’s latest fixture to Alan Shearer, who affects that familiar expression of stoic rage.

He purses his lips, narrows his eyes purposefully, locks his stare on Gary Lineker and delivers a monologue of candid, impassioned condemnation. It’s something he’s getting very good at. He’s had a lot of practice.

“It was embarrassing from start to finish,” was last week’s instalment, delivered in the wake of a dismal 5-1 shellacking by Chelsea. “They’ve got ability in that team but ability is not enough. You need character and you need attitude and I’m not sure they’ve got enough of that. It was hopeless.”

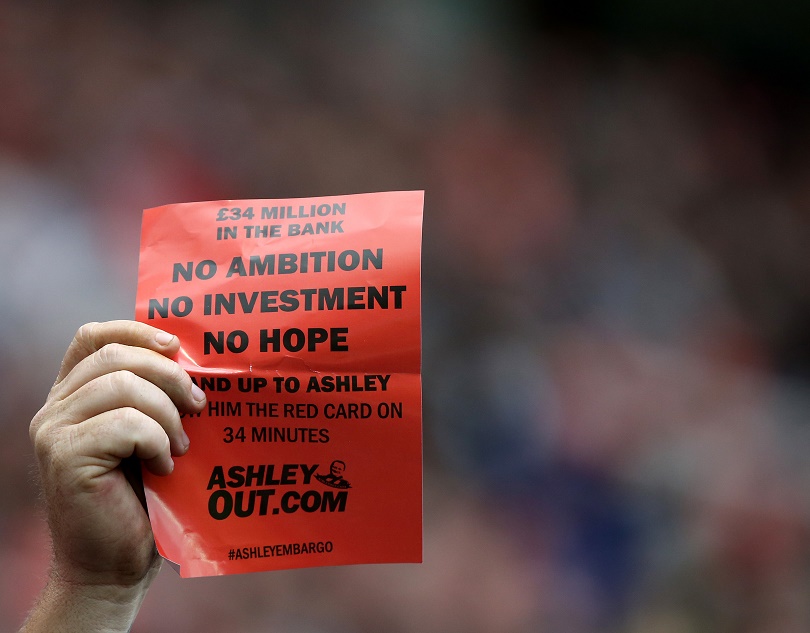

With the depressingly familiar spectre of relegation looming large, a mood of simmering discontent among the fans is starting to froth ominously. Nor is blame limited to the playing staff: “Is there anybody now who doesn’t accept Steve McClaren is part of the problem?” asked one fanzine this week.

Traore scores Chelsea's fifth

Consistent disappointment

That transfer policy, pursued dogmatically and with all the subtlety of a Sharon Stone seduction, has siphoned any sense of ambition from the club’s core

Very little of this can be argued with. And yet by hitting the target so emphatically, the criticisms tabled by Shearer and co. risk missing a much broader, much more fundamental truth.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

“The first and biggest problem at the club is [owner] Mike Ashley,” says Mark Jensen, editor of The Mag, a long-running and popular independent Newcastle site. “In the nine years since he took over we’ve been relegated once, narrowly avoided another two, and are making a good go of it this year as well. The aim remains the same as it’s ever been under his ownership: not to compete for anything, but to simply survive in the Premier League while spending as little money as possible.”

With the exception of the 2011/12 campaign – which is now looked back on as a quirky anomaly – St James’ Park's functioning as a theatre for abject defeatism has transcended any one group of players, any one manager, or any one season. At which point it should be concluded that that these men on the frontline are far more a symptom than they are a cause.

The common denominator has been an ownership regime that has infused squad after squad with a mentality of detached apathy; imbued manager after manager with the same look of weather-beaten resignation.

Buy low, sell high. That transfer policy, pursued dogmatically and with all the subtlety of a Sharon Stone seduction, has siphoned any sense of ambition from the club’s core. Its outcome is a squad full of youngsters with plenty of talent but very little top-level pedigree, and all fully aware they’re not there for the long-term – not a recipe that plays particularly well in a relegation battle.

The policy also overlooks the value of leaders, which translates into Newcastle’s worst on-field habits: a chronic inability to reverse a losing scoreline, and the 31 goals conceded – and seven scored – in just 13 away games.

Recruitment problems

Fans are hardly galvanised by the knowledge that the best they can expect from any new arrival is some impressive form followed by a hasty and profitable sale

On a micro level, the collective forfeiture of resolve and organisation during Saturday’s loss was yet more proof of a profiteering ownership having created a false economy: shorn of experienced team-mates, the young players are being made to look worse than they are and will be worth less money as a result. Which makes Ashley’s business model look self-defeating as well as simply selfish.

Fans are hardly galvanised by the knowledge that the best they can expect from any new arrival is some impressive form followed by a hasty and profitable sale, a la Demba Ba or Yohan Cabaye. And yet those players – the ones who have made a positive impact before moving on – in fact represent the glorious upside of the conveyor-belt transfer policy.

The real malignance lies in the swathes who’ve passed through without so much as a whisper. The likes of Mehdi Abeid, Romain Amalfitano, Mapou Yanga-Mbiwa, Olivier Kemen and Remy Cabella have all come and gone during the last five years, all leaving impressions as enduring as an episode of CSI. None were expensive mistakes, but the cumulative effect – painting the picture of a club with no creed or cause – is seriously costly.

There is no shame in a mid-ranking club selling itself as a stepping stone; Stoke, for instance, have shown how the ploy can lure high-end talent and fuel upward mobility. Newcastle, though, seem intent on painting St James’ Park not so much as a stepping stone but as an airport walkway, a slow-moving road to nowhere for Europe’s professional journeymen to hop on and off at their discretion.

Club and fans detached

Using the shirt to advertise a payday loan company compounded the profound disenfranchisement felt by a proudly working-class fanbase

Hoovering up low-pedigree players in the hope of seeing improvement also runs the risk of amassing difficult-to-shift deadwood. Hence why, nearly five years after joining, Sylvain Marveaux is still at the club, his contribution to the cause standing at 13 league starts and one goal.

Emmanuel Riviere, Yoan Gouffran and Gabriel Obertan all remain on the books too, the trio having collectively accrued a decade of employment at Newcastle – but just five appearances from the start this season.

These are just the squad-level symptoms of Ashley’s process of top-down soul-sapping. Refashioning the club’s famously cathedral-esque stadium as billboard space for an ethically bankrupt retail business is a process that runs in direct opposition to the community spirit of a club that, even more than most, is as much a civic institution as a sporting one.

Using the shirt to advertise a payday loan company compounded the profound disenfranchisement felt by a proudly working-class fanbase.

Same as always

The problem isn’t Ashley’s running of the club as a business, more his systematic draining of its identity in the process

Are there any signs of change? This season’s £73m outlay is the first time under Ashley’s ownership that the club has exceeded the £20m mark. The worry, though, is that it is the same underlying process, with only the fees changing hands having upscaled in accordance with the division-wide windfall.

“That so many of the big January buys were by clubs towards the bottom shows what’s motivated Newcastle’s spending, and that it isn’t unique to them,” says Mark Jensen. “Ashley only allows serious money to be spent when his long-term income stream [of Premier League TV rights] comes under threat.”

The problem isn’t Ashley’s running of the club as a business, more his systematic draining of its identity in the process. Tottenham Hotspur, for instance, is the only club in the league to have made a profit in transfer fees over the last five seasons. They are also the team most imbued with a sense of high-punching collective endeavour, and may win the league. It should not be a binary choice.

No solution in sight

The January signings of Jonjo Shelvey and Andros Townsend – both British, both of whom deal in effort and dynamism – have provided some scraps for the more optimistic fans to feed off

Of Newcastle’s 18-man squad last Saturday, 12 had been at the club for two years or less, seven for under a year. Identity may sound like a wishy-washy concept but it is rooted in real-world tangibles.

The January signings of Jonjo Shelvey and Andros Townsend – both British, both of whom deal in effort and dynamism – have provided some scraps for the more optimistic fans to feed off. “Getting two players who are proven in the division is the one glimmer of hope,” says Jensen.

“The problem is, there’s still an insistence on only buying players who will increase in value. So we end up with a midfielder and a winger when what we’re desperate for is a centre-half and a left-back.”

The real problem for Newcastle is that the source of the club’s problems is so deep than not even the negatives can take their usual, clichéd positive spin. Relegation wouldn’t “provide a much-needed shock to the system”, nor would escaping it offer the chance for “a new start”. Both have happened in recent years; neither have prompted the top-down reform that’s desperately needed.

Unless things change drastically, Newcastle’s indifferent drift into obscurity will simply thrum along, an ocean liner plummeting towards the sea bed as its captain forensically eyes the bank balance.