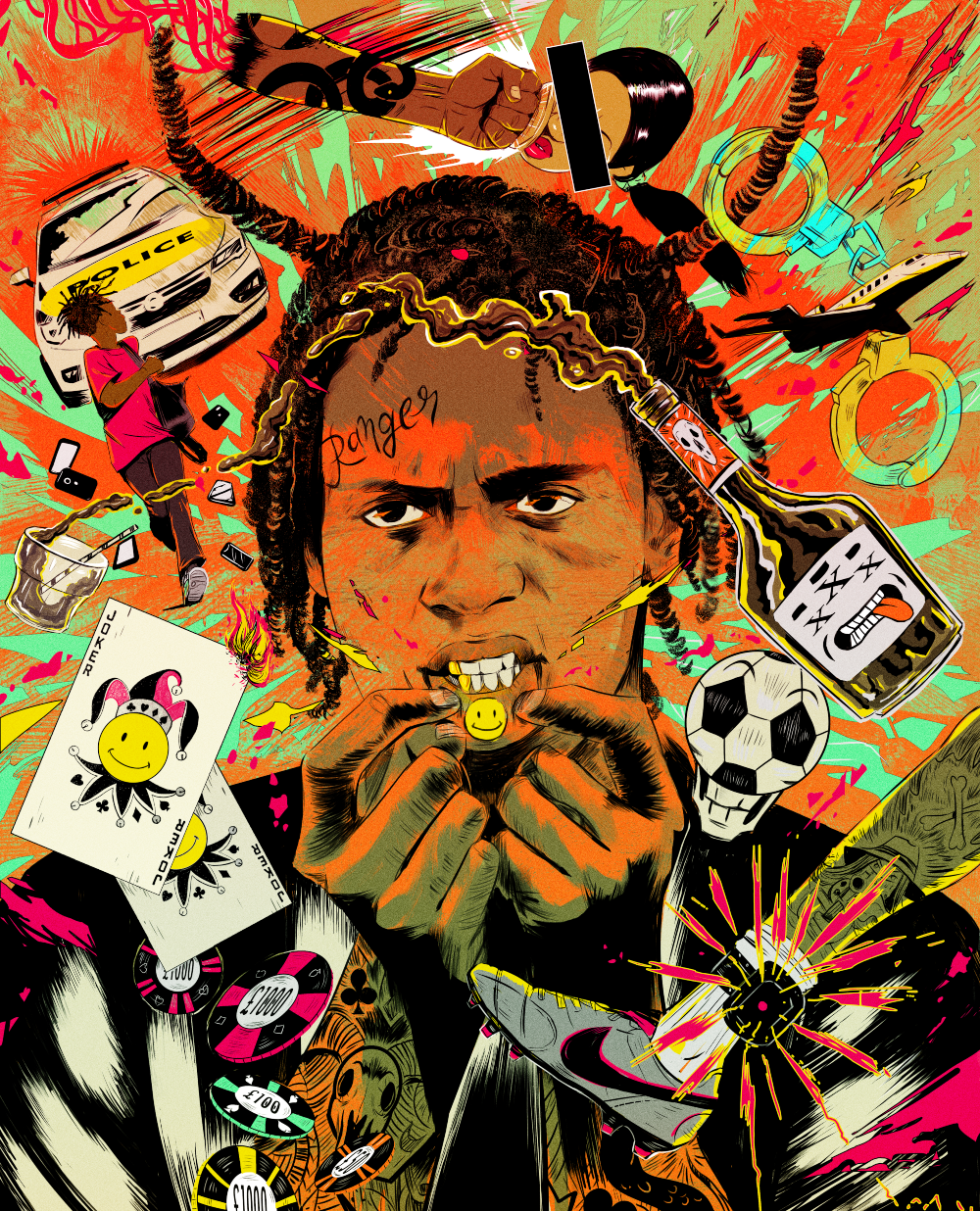

Nile Ranger's long journey back to football: "I’ve reflected on everything I’ve done wrong – and everyone I've hurt"

Nile Ranger was tipped for the very top after making his Newcastle debut aged 18, the striker tells FFT about his troubled past, long list of regrets... and what he'll do with his final chance

This article was first published in August 2020. Interview by Alec Fenn

For as long as I can remember I’ve been trouble, which is strange for a boy whose earliest memories are going to church with his mum as a toddler. In primary school, I’d tell the teachers to ‘go f**k themselves’ and often fight in the playground.

Then in Year 6, I was permanently excluded for hitting a teacher with a dinner tray and almost breaking one of her hands.

Like for many kids, football was an outlet, but it wasn’t enough to keep me on the straight and narrow. Crystal Palace signed me when I was 10 and I played in the same team as Wilfried Zaha and John Bostock, but I lasted only two years there before they released me because of my bad behaviour at school.

People often talk about street footballers who learn their skills on the concrete, but I learned a different trade in the darkest corners of north London.

Nile Ranger's school years were rather unusual

People often talk about street footballers who learn their skills on the concrete, but I learned a different trade in the darkest corners of north London.

In Year 7, while the other kids played football in the playground, I’d steal mobile phones from the blazers being used for goalposts. After school, I’d head straight to Finsbury Park and sell them to a group of Albanian men I’d met through various acquaintances.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Later, I’d roam the streets to steal phones, and the money would just keep rolling in. My mum gave me £2 a day for pocket money, but I didn’t use it to buy sweets – I went to the bookies.

I’d spend hours in a trance watching my cousin playing on brightly-lit slot machines, and then give him my money to gamble for me.

When I was 13, the teachers asked my mum to come to school and sit at the back of the classroom to try to correct my behaviour. It didn’t work. In Year 9, I was kicked out for good after burning my classmates with a Bunsen burner.

I enrolled at a special school, The Octagon, for kids with learning difficulties or behavioural problems. It felt like a mini prison, with smaller classes and more staff to police the lessons and make sure we didn’t run riot.

I was surrounded by bad lads just like me, and it wasn’t long before I was up to my old tricks.

Ranger started out at semi-pro clubs

Football was my one hope of making something from my life. I joined a semi-professional team called Haringey Borough, where there was a decent standard of football and somewhere to channel my pent-up energy.

At least, that’s what should have happened. I was still mixing with the wrong crowd, and one night was among a gang of lads who robbed a nearby high school. I was arrested, bailed for seven months and put on curfew – but that still didn’t stop me. I repeatedly flouted the curfew to rob more houses.

Mum grassed on me to the police, and soon I was arrested for another robbery. They fitted an electronic tag on my ankle but I found a way of slipping it off using some fairy liquid, so I could loot more homes.

I joined another semi-pro club, Romford FC, where I trained during the week and scored goals at weekends, and also enrolled at a football academy run by [former QPR and Nigeria centre-back] Danny Shittu.

The hours in between were spent either robbing houses, gambling or smoking weed, and it was inevitable that those worlds would collide. After one training session at the academy, I stole every mobile phone in the dressing room and was caught red handed with them in my bag. ‘How did these get in here?’ Shittu asked me.

I denied everything, but he wasn’t stupid and banned me from the academy. The next time we met, I was playing for Newcastle and he was at QPR.

It was another self-inflicted f**k-up, but I enjoyed a slice of luck after both of my earlier burglary charges were dropped. That should have been the moment I turned my life around, but instead I went on the rampage with my friends.

Once, we all hopped on a bus and started robbing phones by any means necessary. After looting the top deck we jumped off, boarded another bus and carried out the same attack.

We had more phones than a call centre – but it wasn’t enough. We headed down a street and ripped phones out of people’s hands. A few seconds later, a police car came flying around the corner. S**t. We legged it and chucked our haul into the bushes, but couldn’t get away quick enough.

"I spent three days in the cells."

The officers discovered the stash. I was arrested and taken down to a station, where I spent three days in the cells. Police quizzed me but I had one answer for every question: ‘No comment’. They charged me with armed robbery and I was bailed again, pending a date for a trial. This time it was serious.

While I waited for a letter to arrive in the post, I continued to break my curfew. On one successful afternoon I came away with a laptop worth £700, but was then caught in possession of a stolen iPod and arrested again.

I was 15 and my mum was considering chucking me out. I begged her to give me one more chance, so in 2007 she sent me to a football academy at Southgate College – they provide academy-level training and have links with pro clubs.

We played a pre-season match against Southampton’s youngsters and I came off the bench, scored twice and won us the game.

Weeks later my coach got a call from Southampton, who wanted to take a closer look at me. I trained with the youth team and was offered a two-year scholarship within days.

Southampton was a fresh start away from the temptations of north London. They paid me £110 a week and put me up in a lodge with the rest of the academy players, where I became good mates with Bradley Wright-Phillips, Nathan Dyer and David McGoldrick.

I was soon scoring goals for fun and having fun off the pitch, too. At night, I sneaked out of the lodge and jumped into McGoldrick’s car with Wright-Phillips and Dyer, before heading to nightclubs. Eventually, my landlady grew wise to my disappearing act and told the club, which led to a fine.

Southampton didn’t know anything about my chequered past, and the academy director got a shock when the club received a letter from the Crown Prosecution Service ordering me to stand trial over armed robbery.

In court, the club told the judge about my talent and how I’d begun to mend my ways, but the damage was done. I was sentenced to four months in a Young Offender Institution. My legs turned to jelly in the dock, and I cried as I heard my aunt sobbing in the gallery.

Her son and my cousin, Michael, would be joining me behind bars. We were locked up for 23 hours a day, although I tried to stay sharp by playing for the prison football team.

I was released after two months of my sentence and went back to Southampton, where the club moved me into a flat with my mum so she could keep an eye on me.

I started scoring goals again, but hit the self-destruct button when I pinched a hoard of boots, training kit and even a staff member’s box of chocolates. I hid them in a bush and was planning to go to London, but a coach found them.

Nigel Pearson wouldn't give Ranger another chance

It didn’t take long to find the perpetrator, and despite begging first-team manager Nigel Pearson, Southampton showed me the door.

Agents didn’t seem bothered about that. My phone kept ringing with offers and I was quickly on trial at Swindon. I scored an overhead kick and they offered me £250 a week, but before I could accept, my agent called and asked me to meet him at a nearby Burger King.

There was a two-year contract on the table from Newcastle worth three times as much, plus a £20,000 signing-on fee. On paper it was a no-brainer, but I was in two minds about living so far away from home. It took several chats with [executive director] Dennis Wise to get me to sign.

I stayed in digs with two other youth-team players and had a really strict landlord called Glenn, who insisted that we all ate at the dinner table every night and went to bed at certain times. The routine helped me, and I soon started scoring goals for the under-18s and reserves.

Kevin Keegan called me up to train with the senior team. The first time I ever met him, I didn’t know what to say and ended up blurting out, ‘All right, Keegan!’ He bent over double laughing, but warned me that I was to call him ‘gaffer’ from then on.

Months earlier I’d been in prison – now I was getting changed next to Alan Shearer and Michael Owen. It was mad. I kept my head down, and within a few weeks was named on the bench for a Premier League game against Arsenal at the Emirates Stadium.

We travelled down on a private jet, and I remember Owen and Nicky Butt shaking hands on a £500 bet for whose bag would appear out of the luggage carousel first. It was a different world. We lost 3-0 and Keegan resigned weeks later, but I stayed around the first team while scoring 15 goals for the U18s and seven for the reserves in 2008-09.

I was rewarded with a new three-and-a-half year deal. The contract was worth £10,000 a week and included a string of bonuses if I scored goals and made a certain number of appearances. I was still only 18 and hadn’t made my first-team debut.

That changed in August 2009, though, when I came on in the 89th minute of a Championship game at West Bromwich Albion. It took me until December to score my first goal, away at Coventry, but I added a second in a January victory over Crystal Palace at St James’ Park.

I made 30 appearances that season as we won promotion to the Premier League at the first time of asking, but that didn’t paint the full picture.

Off the pitch I’d been in trouble with manager Chris Hughton, who’d been appointed at the beginning of the 2009-10 season. I turned up late for training more than once after developing a taste for midweek nights out, and was also spending far too much free time in casinos.

I gambled £30,000 in a two-month period and borrowed £70,000 from Hatem Ben Arfa, Steven Taylor and Fabricio Coloccini to pay my debts. The club found out and instantly banned me from every casino in Newcastle, while Coloccini sat me down and warned me about the dangers of gambling.

"I was banned from driving for a year."

Mark Viduka was a positive influence too, often advising young players to save their money. Alan Smith was another good role model who drove a battered old car despite his big earnings. I still didn’t listen.

A £96,000 promotion bonus landed in my bank account and I spent a chunk of it on a brand new Range Rover. It soon caught the gaffer’s eye. Andy Carroll then got hold of my car keys at training and parked it in Hughton’s space.

The gaffer warned me to spend my money wisely and not let it go to my head, but it went in one ear and out the other. I was still doing my bit on the pitch, and scored in a 4-3 League Cup win at Chelsea in September 2010. After the game, I was pulled aside by a club official and told that several tabloid newspapers were going to print a photograph of me holding a gun the next day.

My WhatsApp profile picture was me posing with a BB gun, and someone had sent a screenshot to a journalist. The club fined me two weeks’ wages, but that was loose change compared to the new five-year contract I was given just three months later.

"When officers tried to arrest me, I panicked and shoved them away."

Newcastle had shown me loyalty but I only repaid them with hassle. After another midweek night out, I drove home with my girlfriend in the passenger seat.

Police stopped and breathalysed me – I was over the limit and locked in a cell until the morning, handed a £3,000 fine and banned from driving for a year. Alan Pardew succeeded Hughton, who had been sacked in December 2010, and grew tired of my poor timekeeping, making me train with the academy kids as punishment.

To make things even worse, I ended up in court after hitting two men who had racially abused and then tried to attack me in the city centre.

When officers tried to arrest me, I panicked and shoved them away – so got charged with assaulting the men and the policemen.

I pleaded guilty and thankfully CCTV footage supported my story, meaning I was given a 12-month conditional charge.

I spent 2011-12 on loan at Barnsley and then Sheffield Wednesday [scoring on the last day of the season to help the Owls win promotion to the Championship], which meant I at least played a bit of football, but winning my place back at Newcastle appeared impossible.

I was growing frustrated, and lashed out at fans on Twitter for criticising the team during a disappointing run of form. They turned on me, and after that there was no way back. I was arrested again in January 2013 on suspicion of rape after sleeping with a girl on a night out.

That was no more than a one-night stand, but the police decided to charge me and it was enough for Newcastle to cancel my contract. F**k.

Newcastle – 2009-2013

Barnsley (loan) – 2011

Sheffield Wednesday (loan) – 2012

Swindon – 2013-2014

Blackpool 2014-2016

Southend –2016-2018

Spalding – 2020-2021

Southend – 2021

"I was fined £3,000 for criminal damage"

Teams didn’t want to come near me. I had a rap sheet longer than a shopping list and a rape charge hanging over me, but after spending five months as a free agent I signed a 12-month deal with Swindon on £4,000 a week.

By this point you’d think I’d have learned my lesson – you’d be wrong. I scored eight goals in 23 League One games, but was dropped multiple times for turning up late to training or not turning up at all.

There was some good news when I was cleared of rape in March 2014, but I was arrested again for hitting a female friend in the face after drinking three bottles of Hennessy Cognac.

Fortunately she didn’t press charges, but I was fined £3,000 for criminal damage after kicking in my door at the end of that night having lost my keys. Unsurprisingly, Swindon terminated my contract in May.

Given my love for a bet and night out, joining Blackpool three months later wasn’t a great decision – but I was desperate and they knew it.

I was given a deal worth £150 a week and £3,000 a game if I played. I scored two goals in 14 Championship appearances between August and November, but I wasn’t happy.

I was living in a hotel attached to the stadium, and my girlfriend left me after finding out I’d cheated on her in Blackpool. She drove back to London, and I sped after her down the motorway for about 30 minutes before the police pulled me over.

I went back up north, but after being left out of the squad for a home match against Birmingham in early December, I returned to London and stayed there for the next six months.

The club fined me every time I missed a training session, but I didn’t care any more. I only had a 12-month deal and figured they wouldn’t extend it at the end of the season.

Strangely, they then activated the one-year option in my contract and told me to return for pre-season. I turned up four weeks late, by which point they’d already played four friendlies. I was made to train on my own, running up and down sand dunes on the beach, but couldn’t get anywhere near Neil McDonald’s first team despite issuing a public apology about my behaviour.

I was eventually released in February 2016.

Phil Brown gave Ranger a lifeline

I didn’t play again until August – my first game since November 2014 – after signing a one-year deal with Southend. My contract was worth peanuts, but after scoring two goals at Bury and another at Oldham, Phil Brown gave me a new three-year contract on £3,000 a week.

He probably regretted it when I was charged with online bank fraud a few weeks later. With another court case hanging over me I ploughed on, scoring in four successive league games from mid-March to early April. But the joy was short-lived.

In May, soon after the season had finished, I was sentenced to eight months in jail after admitting conspiracy to defraud. I spent 10 weeks in Pentonville prison before being released for good behaviour, but had to wear a tag on my ankle for five weeks and was given a 7pm curfew which meant I couldn’t play in any midweek evening games.

Southend showed great loyalty towards me and I played 21 times during the first half of 2017-18, but my contract was terminated in January after they finally ran out of patience with my lateness.

"I’m treated as the Osama bin Laden of football."

Since then, the game has pretty much washed its hands of me. I’m treated as the Osama bin Laden of football. I went to train with Oxford for several weeks in 2018, but rejected a contract there because I felt the terms weren’t good enough.

Rochdale offered me £1,000 a week last season after a brief trial, but I turned it down because they wanted me to live in an apartment with a new team-mate and his girlfriend to make sure I didn’t slip back into my old ways. In hindsight, they were both really stupid decisions.

After leaving Southend, I moved back home with my mum and played five-a-side a couple of times a week just to stay fit – but it’s a world away from professional football.

I’ve had two long years to reflect on everything I’ve done wrong and the people I’ve hurt along the way. I can’t blame anyone else – it’s all been self-inflicted and I’ve had more than my fair share of chances to change. I turned 29 in April and know I don’t have time to waste.

I hope and pray I’ll get one last chance. If I do, I’m ready to grab it with both hands.