Opinion: Wake up – it’s time to acknowledge that the notion of a super-coach is nonsense

The football world bubbled with hysteria at the prospect of Mourinho, Guardiola, Conte and Klopp in the same league this season – but only one of them is enjoying success so far this season. It’s time to get a grip, writes Alex Hess

Given how the Premier League’s entire identity has depended on expunging everything that happened before 1992, it’s fair to say that top-flight football in England has a fairly dubious relationship with history.

It’s a relationship that isn’t just played out in this erasure of a century’s worth of events, though, but also in how the Premier League – and much of its media coverage – likes to think history works.

The ‘great man’ model came from the work of a number of historians in the 19th century. It is the idea that the course of human history is carved by influential leaders – great men – who impose their will on the rest of society. According to this theory, it is men like Julius Caesar, Alexander the Great and Che Guevara who, by starting revolutions, leading armies into battle and striking trade deals, chart the course of human progress and whittle civilisation into the shape it’s in today.

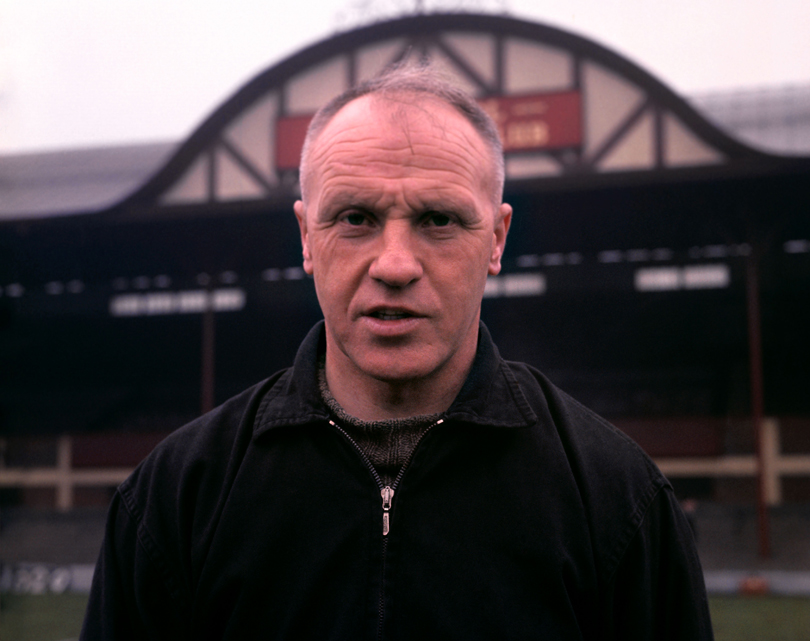

England’s national game has always lauded the cult of the manager: Chapman, Shankly, Clough, Ferguson and Wenger are just some of the men whose legends have them single-handedly rebuilding entire clubs from their foundations

Cloudy comparisons

You might see where we’re going here. Swap the above names for those of Jurgen Klopp, Jose Mourinho and Pep Guardiola, and you’ve got a cursory model of how British football likes to believe its world functions. In comparison with Che Guevara & Co., the magnitude of men like Klopp, Guardiola and Mourinho is minor (though you wouldn’t know it from some of the coverage, or fanatical followings they inspire) – but the role in which English football has cast them is broadly the same: right now, we’re told, it’s these men who are plotting the course of sporting history.

There’s nothing new about this. For pretty much as long as it’s existed, England’s national game has lauded the cult of the manager. Chapman, Shankly, Clough, Ferguson and Wenger are just some of the men whose legends have them single-handedly rebuilding entire clubs from their foundations, bending British football to their iron will, and it’s their shoes into which the Premier League’s recent influx of super-coaches have stepped.

But with these coaches having arrived at their new clubs to the sort of fawning fanfare that would have made Caesar blush, the opening months of the season have provided a sturdy counterpoint to the heady expectations prompted by their appointments.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Manchester is blue

Lately the Manchester City crowd, rather than murmuring their gratitude for Guardiola’s possession-at-all-costs playing style, have taken to berating their players’ high-risk defending

At both Manchester clubs, the man in charge has found himself straightjacketed by the culture he’s landed in. At United, Mourinho (whose ‘Special One’ moniker on these shores could hardly put our adherence to the ‘great man’ theory in plainer terms) has been powerless to rectify the structural incoherence at club level. He is a coach whose success relies on his players’ unquestioning, selfless subservience, put in charge of a squad assembled according to a galacticos-style model of egos and profile.

The result has been predictably disjointed. Before the season started, Mourinho’s singular greatness convinced many that United would march to the title; halfway through, they’re already 13 points off the lead.

Manchester City were chosen by Guardiola partly due to their lack of history and expectation, but his introduction to England hasn’t gone as smoothly as he’d hoped. Lately, the City crowd, rather than murmuring their gratitude for Guardiola’s possession-at-all-costs playing style, have taken to berating their players’ high-risk defending, most likely prompted by the suspicion that encouraging Aleksandar Kolarov to channel his inner Franz Beckenbauer may not always end well.

So far the suspicion has proven entirely rational: City started like a steam train but have fallen away amid a tide of defensive ineptitude; they currently sit fourth after a 4-2 humping at Leicester in which they were three down inside 20 minutes.

Jurgen Klopp came into a far more welcoming culture – no club deifies its manager the way Liverpool does – but again this great leader has been thwarted by a distinct lack of greatness among his servants. Make no mistake, Klopp’s effect on Liverpool has been impressive, but this season has shown that finely tuned gegenpressing routines only count for so much when you have a keeper who’s chucking them in every week.

The outlier to this rule is of course Antonio Conte, whose management has taken Chelsea from 10th to top, and whose tactical switch instigated a nine-game winning run. Even if Conte’s achievements have been warped by the aberration that came before, the transformation has been spectacular. Right now, he is a one-man argument in favour of the Premier League’s ‘great man’ theory.

Correlation and cause

Conte is drawing huge praise for turning Chelsea around, but this praise is assigned by a media which struggles to comprehend any other model than the ‘great man’ one. In almost every analysis, the unspoken presumption is that Chelsea’s hot streak is the result of Conte enacting his masterplan, rather than it simply being a collection of very good footballers playing very well.

It’s hard to know how much we mistake correlation for causation in these instances. Is Conte a great coach, or is he simply in change of a great team? Was Mourinho the great man who turned Chelsea into a winning machine in the mid-noughties, or was that someone else? Is Guardiola a visionary aesthete on a par with Kubrick and Coppola, or is he simply football’s James Cameron, leapfrogging from one megabucks project to the next and lapping up the applause when his all-star cast inevitably deliver success?

4 – This is the third time a team managed by Pep Guardiola have conceded 4 in a league game (Atlético in 2009 & Wolfsburg in 2015). Upset.

— OptaJoe (@OptaJoe) December 10, 2016

The answers are impossible to know, and almost certainly a bit of both, but the point is that this huge expanse of middle ground goes largely ignored by a football culture whose default setting is to attribute a team’s performance entirely to the man in charge.

Not long after it had been popularised among historians, the ‘great man’ model was dismissed as a simplification by a group who argued that social, economic and political factors would always outweigh the influence of an individual. These so-called ‘great men’, according to the critics, are society’s products as much as they are its forgers. And so the model gave way to a more nuanced one – a moment of enlightenment that English football is yet to reach.

Reality check

The great irony here is that there are few, if any, industries where the leader figure is as dispensable as in the Premier League. For a world that spends so much time expounding the ‘great man’ model, British football tosses these great men aside with astounding frequency.

This suggests either a lack of faith in the individual – that he was never great in the first place – or, more likely, the underlying, unspoken knowledge that the whole thing carried a whiff of nonsense to begin with. That a coach, great as he may be, is only ever a coach.