Our Manc on the Kop: Why Liverpool vs Man United is More Than A Game

Can FFT's Andy Mitten, diehard Red Devil, survive behind enemy lines?

My head feels like it’s going to explode. Barely 10 yards in front of me, John O’Shea is wheeling away in celebration and the stunned Scouse silence means the joyous screams of the United’s players are audible.

We’ve beaten arch rivals Liverpool in dramatic and, many will say, undeserved circumstances: 1-0, at Anfield, with a killer late goal after defending for much of the game. We’re now 12 points clear in the race for a title most fans considered out of reach last August.

As the players shout at lung-bursting volume and exchange frenzied hugs, I have to contain the euphoria of this perfect, body-tingling buzz, not showing the slightest sign of joy. I’m on the Kop, a lone Mancunian in a mass of 12,000 fuming Liverpool fans.

After glancing one last time at the ecstatic United players and 3,000 delirious travelling fans in the Anfield Road stand, I jog back to the car through the streets of dilapidated and boarded-up Victorian terraces which surround Anfield, past pubs, the ones closest to the ground teeming with fans from Bergen and Basingstoke, with their painted faces, jester hats and replica kits. It reminds me of Old Trafford.

Finally, in the relative safety of the car, I let my emotions go and punch the air repeatedly, before looking out to see a man staring at me from his front room window. He raises his two fingers. It’s no ‘V’ for victory and I don’t need assistance from a lip reader to know what he’s saying. It’s time to get on the East Lancs Road and back to Manchester.

My mood had been so different before the match as I queued to get onto the Kop for the first time in my life. I’d not seen a United fan all day, save for the Mancunian ticket touts working alongside their Scouse counterparts behind the Kop.

“We’re in the same game and we all know each other,” explains one. Whether you’re at the Winter Olympics in Japan or Glastonbury, the vast majority of spivs will be Mancunian or Scouse, an unholy alliance of wily, streetwise grafters.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Like me, 95% of the United fans at Anfield wore no colours, but paranoia gripped me as I reached my seat. It would take just one person to suss I wasn’t a Liverpool fan and I’d be in serious trouble. I wasn’t going to attempt to fit in by trying a Scouse accent, mutilating words like chicken to a nasal ‘shickin’ or calling people ‘la’, ‘soft lad’ or ‘wack’, but I wasn’t aiming to advertise my allegiances either.

“Alright mate,” said the lad next to me in a North Wales accent.

“Alright mate,” I replied, cagily. They were the last words I spoke all game.

When the fans sang You’ll Never Walk Alone I focused on events on the field. I did the same when they chanted, “You’ve won it two times, just like Nottingham Forest,” in reference to United’s two European Cups compared with Liverpool’s five.

I ignored the constant anti-Gary Neville abuse, was surprised that Ronaldo wasn’t booed once – “We don’t go for that ‘little Englander’ nonsense,” a Scouser explained later – and stunned that the Kop applauded Edwin van der Sar as he took to his goal. The Dutchman applauded back warmly.

All around me, Liverpool’s flags continued the European theme: ‘Paisley 3 Ferguson 1’ reads one. Liverpool are obsessed with flags. One piece of cloth even has its own website; others try hard to be examples of the famed Scouse wit.

At half time, I met Peter Hooton, former lead singer of The Farm, and lifelong Liverpool fan by the Kop’s refreshment kiosks where the Polish catering staff struggle to decipher the Scouse brogue.

“What are you going to do when we score?” he asked.

“When?”

“When.”

But Liverpool didn’t score.

It is commonly agreed that there is rising tension between fans of Liverpool and Manchester United. At Old Trafford last October, both clubs sought to defuse the increasingly fraught atmosphere.

During an FA Cup game at Anfield in February 2006, a Liverpool fan had hurled a cup of excrement into the 6,000 United fans on the lower tier of the Anfield Road, hitting one on the head. After the game, Liverpool fans rocked the ambulance carrying United striker Alan Smith to hospital – though Smith later received hundreds of cards from well-wishing Liverpudlians, keen to stress that this was something which made them ashamed.

At Old Trafford, greats like Denis Law, Ian Callaghan, Bobby Charlton and Roger Hunt were paraded on the pitch before the game and a penalty competition was held between rival fans. It didn’t work. Not that anyone was too surprised given the levels of animosity. Liverpool fans approaching Manchester that day had been greeted with freshly-painted ‘Hillsborough ’89’ graffiti on a bridge over the M602 in the gritty United heartland of Salford. Closer to the stadium, another sprayed message bore the legend: ‘Welcome to Old Trafford, you murdering Scouse bastards.’

The teams were led out by Gary Neville, punished for the crime of celebrating in front of Liverpool fans the previous season, and Steven Gerrard. Both understand the United-Liverpool rivalry acutely, given their lifelong affinity with the clubs they captain. Both would rather stick pins in their eyes than join the enemy. Both were subject to plenty of abuse in the songs which rang round the stadium, which also rehearsed some enduring stereotypes about the two clubs and the inhabitants of their cities.

United fans: “Gary Neville is a Red, he hates Scousers.”

Liverpool fans: “Gary Neville shags his mam, up the shitter.”

United: “Steve Gerrard, Gerrard, he kisses the badge on his chest, then puts in a transfer request, Steve Gerrard, Gerrard.”

Liverpool: “Walk on, walk on, with hope in your heart, you’ll never walk alone.”

United: “Sign on, sign on, with hope in your heart, you’ll never get a job.”

Liverpool: “We won it five times in Istanbul, we won it five times.”

United: “We’ve won it two times without killing anyone, we’ve won it two times.”

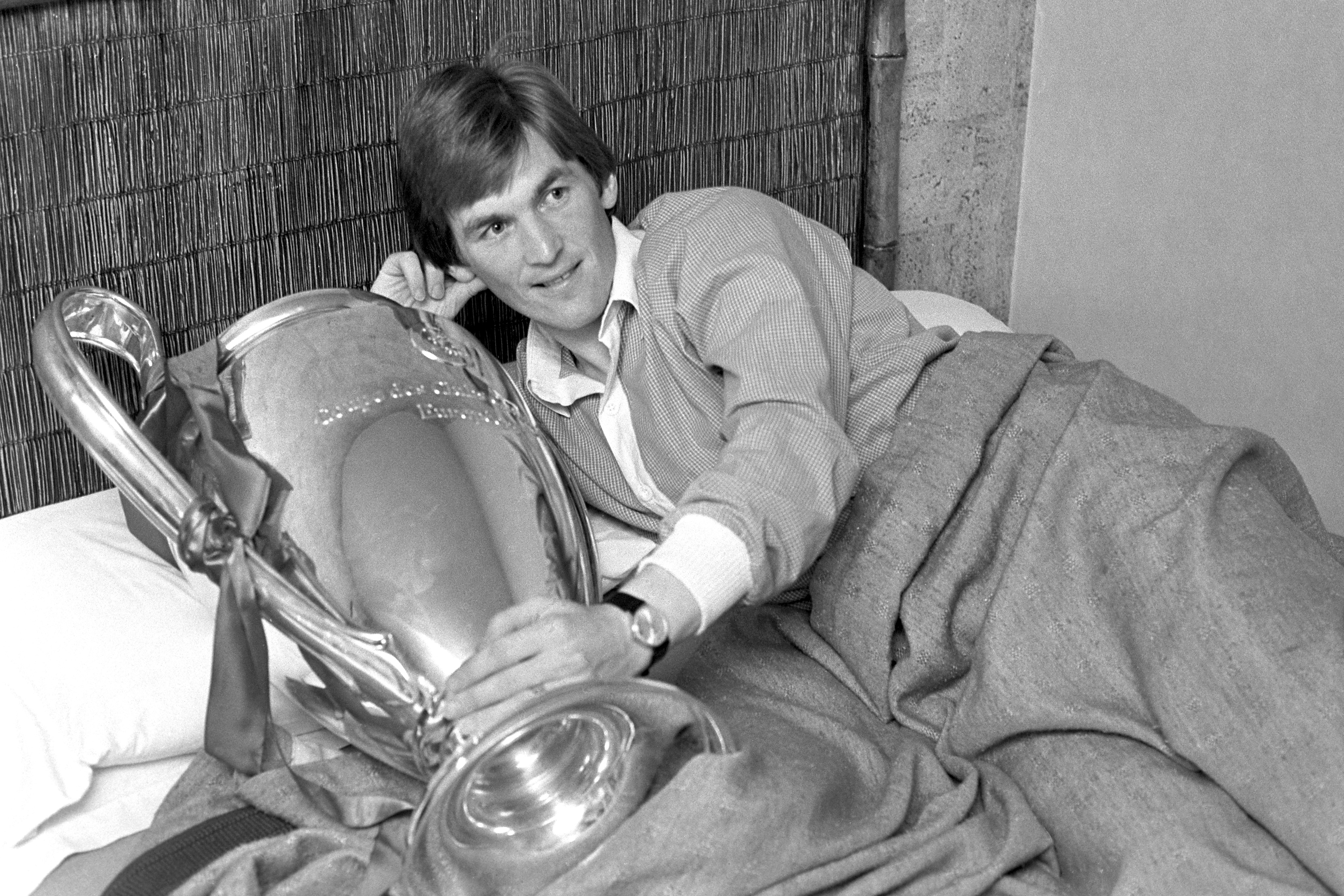

Liverpool: “All around the fields of Anfield Road, where once we saw the king Kenny play – and he could play...”

United: “Murderers, murderers.”

Liverpool: “S**t on the Cockneys, s**t on the Cockneys tonight.” [A surprising reference to United’s perceived out of town support – United are usually loathed precisely because they are Mancunian].

United: “If you all hate Scousers clap your hands.”

Liverpool: “We all hate Mancs and Mancs and Mancs.”

United: “Park, Park wherever you may be, you eat dog in your own country. But it could be worse, you could be Scouse, eating rat in your council house.”

Liverpool: [To Wayne Rooney] “Once a blue, always a Manc.”

United: [For Rooney] “Once a blue, always a Red.”

Liverpool: [To Rooney] “You fat bastard.”

United: “City of Culture, you’re having a laugh.”

Liverpool: “Oh Manchester, is full of s**t.”

United: “Does The Social know you’re here?”

Liverpool: [After their team had gone 2-0 down] “Who’s that lying on the runway, who’s that dying in the snow? It’s Matt Busby and his boys making all the f**king noise, because they can’t get the aeroplane to go.”

United: “You killed your own fans.”

NEXT: The common ground that divides

Divided by common ground

Like all the greatest rivalries, it’s the common ground that divides the most. United and Liverpool both hail from largely working-class, immigrant cities with huge Irish populations. Just 35 miles apart in England’s North West, both were economic powerhouses who enjoyed a friend/foe relationship by the 19th Century.

Liverpool considered itself the greatest port in the world, gateway to North America for millions and a key trading post for the Empire. Manchester was ‘Cottonopolis’, the first city of the Industrial Revolution – hence the phrase ‘Manchester made and Liverpool trade’.

Civic co-operation in anticipation of greater wealth ensured that the world’s first passenger railway was opened between the cities in 1830, but by late 1878, the year Manchester United were formed as Newton Heath, a worldwide trade depression left Manchester grappling with economic stagnation and labour migration.

Liverpool was blamed for charging excessively high rates for importing the raw cotton spun in Lancastrian mills and Manchester’s solution was to give the city direct access to the sea to export its manufactured goods, thus cutting out the middle man of Liverpool.

The proposal of a canal big enough to carry ocean-going ships infuriated Liverpudlians. Scouse backlash against the canal ranged from music-hall songs and pantomime references to reasoned economic argument.

None of it prevented the Manchester Ship Canal being built and the city became Britain’s third busiest port, despite being 40 miles inland. This is why the United crest has a ship on it. But this was only a temporary respite for Manchester.

With the end of the British colonies and the introduction of container ships, Liverpool’s port became less viable, while the disintegration of the textile industry hit Manchester and both cities suffered generations of economic decline.

Extreme deindustrialisation and suburbanisation was coupled with growing unemployment and poverty among the proletariat. The nadir was marked in 1981 by violent riots in Manchester’s Moss Side and Liverpool’s Toxteth districts.

Yet when it came to football and music, both cities punched above their respective demographic weights, making them special to millions around the globe, but also reinforcing and extending the rivalry.

On the pitch, enmities were not clear cut. Manchester City were the bigger Mancunian club until the Second World War, while Everton were often the pre-eminent Merseyside force. Indeed, the rivalry between United and Liverpool was respectful until the 1960s, with United players even going to watch Liverpool when they didn’t have a game.

“We’d stand on the Kop,” recalls Pat Crerand, a hard-tackling midfielder turned pundit. “The Scousers would have a word, but it was good-humoured.” Bill Shankly used to call Crerand at home every Sunday morning for a friendly football chat. Shankly and the United manager Matt Busby, who both hailed from Lanarkshire mining stock in Scotland, were also close and Busby had played for Liverpool.

“I always had great respect for Liverpool Football Club and Bill Shankly,” adds Crerand - although the respect didn’t stop him, in his early ’70s role as United’s assistant boss, from snaring Lou Macari in the Anfield main stand just as he was about to sign for Liverpool.

Liverpool and Manchester are working-class cities that have produced two of the greatest football clubs in the world"

"When I go to Anfield now, I speak to long-standing Liverpool fans who can’t put up with what the rivalry has become: the hooliganism and the nastiness. Liverpool and Manchester are working-class cities that have produced two of the greatest football clubs in the world. People should be proud of that, but they’re not.”

United had the hegemony in the 1960s – twice league champions and the first English team to win the European Cup. Not since that decade has a player left United for Liverpool or vice-versa (Phil Chisnall was the last, in April 1964).

Liverpool were far superior to United in the 1970s and ’80s, winning four European Cups and 11 league titles as United endured 26 title-free years, but United were usually the better-supported club and matched Liverpool in head-to-head encounters. And even as Liverpool had the success, United enjoyed a reputation which rankled with Liverpool fans who thought it undeserved.

By the ’80s, the rivalry had become vicious, with United’s Scouse manager Ron Atkinson describing a trip to Anfield as like going into Vietnam. Big Ron’s experiences fighting the Viet Cong have not been fully substantiated, but he can be forgiven for exaggerating – he’d just been tear-gassed.

We got off the coach and all of a sudden something hit us. I thought it was paint fumes, but it was tear gas"

“We got off the coach and all of a sudden something hit us,” Atkinson recalls. “I thought it was paint fumes, but it was tear gas. In our dressing room before the game there were a lot of fans, Liverpool fans too, kids, all sorts, eyes streaming. Clayton Blackmore was so bad he wasn’t able to play. I was in an awful state.

"I’d run in and there’d been two blokes standing in front of the dressing-room door. I was blinded and I’d pushed one of them up against the wall. Afterwards, [assistant manager] Mick Brown said ‘What have you done to Johnny Sivebaek?’ I said, ‘What are you on about?’ We’d signed Sivebaek the week before and in his first game, against the European champions, he was gassed as he got off the coach and then hurled against the wall by his new team manager. No wonder he didn’t perform that day!”

Liverpool fans frequently sang songs about the 1958 Munich air crash, but stopped for a time after the 1989 Hillsborough disaster. United fans barely sang about Hillsborough until a minority changed that recently. Yet for every United fan who stoops so low, you’ll find one who respects the continued boycott of The Sun on Merseyside and the continuing campaign for justice for the 96 who perished.

For United, no matter how dangerous the trip to Anfield became, it remained one of the most eagerly-awaited games of the season because it contained all the edge, passion and vitriol you’d expect from a long-standing cultural and social enmity between two teams whose cultural influence extends far beyond their city boundaries.

In the 1990s, Liverpool’s demise coincided with United’s ascendancy under Alex Ferguson. Asked to list his greatest achievement at United, Fergie once replied: “Knocking Liverpool off their f***ing perch. And you can print that.” That wasn’t quite how Scousers intended it to be when they unleashed their ‘Form is temporary, class is permanent’ banner in 1992 as United squandered a league title at Anfield.

In contrast to the hooligan-blighted ’70s and ’80s when Liverpool were on top, the Sky-led football boom allowed United to capitalise on their success and accelerate into a different financial league by regularly expanding Old Trafford while Liverpool were hampered by Anfield’s capacity. United were so commercially successful that fans objected to the 2005 Glazer takeover on the grounds that they were not needed, while Liverpool fans welcomed their new U.S. owners in 2007 because they are.

Both clubs fill their grounds but Old Trafford has over 30,000 more seats than Anfield, allowing United to make more than £1.4 million per home match than Liverpool. Liverpool only have to look east for the justification for building a new stadium.

NEXT: Drinking with the enemy

Drinking with the enemy

It’s three hours before kick-off at Anfield and I’m sitting in a pub full of Liverpool fans in Liverpool city centre. Among them is the novelist Kevin Sampson, author of seminal tomes like Away Days and Powder. Reading Powder and knowing that Sampson was a Liverpool fan, I interviewed him for the United We Stand fanzine in 1999.

I met him at Lime Street and it remains the most popular interview in the fanzine’s 18-year history, although we received three letters from readers appalled at us for ‘fraternising with the enemy’. It should have been a lunchtime pint, but extended to an overnight stay as Sampson introduced me as a curiosity figure to assorted Liverpool characters who claimed they’d never met a Mancunian United fan before.

Some didn’t want to socialise; they didn’t want to like what they had spent a lifetime loathing. They were content with the status quo: happy to reinforce stereotypes, exaggerate prejudices and ignore the evidence that the two clubs are almost too alike to admit it.

United fans were the same, perpetuating the clichés of Scousers as employment-shy thieves and passing over the statistic that you are twice as likely to get your house burgled in Manchester (which has burglary rates three times the national average) than in Liverpool.

It’s the same in the pub today but there are signs of grudging respect.

“Is there anything you respect about Manchester United?” I ask a table of hardcore Liverpool fans.

“Paul Scholes,” comes one reply.

“Ryan Giggs,” another.

“I don’t like Gary Neville, but I respect the way he signs contract after contract at United. We’d love a player who celebrated so passionately against his main rivals.”

“Why are United fans obsessed with Liverpool?” asks another. “All your songs are about Liverpool. Ours are too, but we support Liverpool.”

One thing we do all agree on is a decline in the atmosphere inside both grounds. Sampson is now behind a campaign to ‘Reclaim the Kop’. In October 2006, he wrote an impassioned plea on a Liverpool website regarding his club’s support. It came after Liverpool had played Bordeaux, when sections of the Anfield crowd taunted 3,000 Frenchmen with chants of “Who are ya?” and “You’re not singing anymore”.

“It was embarrassing,” reads the website. “These fans had welcomed travelling Reds, and here, at Anfield, we were ridiculing them. This is NOT the Liverpool Way. We led from the front. We never followed. Be it pop music, terrace chanting, fashions; we were pioneers in the British game.

"The aims of ‘Reclaim the Kop’ are to promote the Kop’s traditional values, its behaviour and its songs. It aims to encourage fair play and respect towards the opposition; to promote the Kop’s traditional songs and chants; to encourage wit and creativity; to rebuild the camaraderie and individuality of football’s greatest terrace.”

“Our support needs sorting out before the quilts [the antithesis of the streetwise fan] have watered us down to nothing,” added Sampson.

Our support needs sorting out before the quilts have watered us down to nothing"

It would be easy to attempt to score cheap points at the idea of organised spontaneity, but United fans have gone through exactly the same. Despite great success on the pitch, the atmosphere inside an increasingly commercialised Old Trafford withered throughout the 1990s. The ‘singing section’ in the Stretford End is contrived, but was needed to kickstart a lame atmosphere which still pales alongside past decades.

Like Liverpool fans, long-standing United fans cringe at elements of the club’s glory-hunting support. There is tension and in-fighting within both fan bases – hardly surprising given that they are so big. Like Liverpool, United hate the way opposing clubs bump up the price of tickets for away fans – a rich club doesn’t mean rich fans. Both clubs are regular visitors to Europe and have similar tales of police brutality.

Many on both sides are indifferent to the fortunes of the England national team, preferring pride in their own city and team. The laddish fan elements dress in a similar way, listen to the same music and note the same cultural influences.

When news filtered through recently that the Salfordian ‘Mr Madchester’ Anthony H Wilson had cancer, there was as much respect on Liverpool websites as on any United one – despite Wilson once presenting Granada’s regional news wearing an FC Bruges rosette on the eve of Liverpool’s 1978 European Cup Final against the Belgians.

Both fans talk with pride about the renaissance brought by new developments in their cities after decades of decline. Yet for all the similarities, there remain stark differences between the cities. “Liverpool has a very small middle class,” explains one Anfield season-ticket holder who lives in Manchester. “As soon as people get money they leave.”

Several Liverpool and Everton players live in Manchester’s suburbs and shop and socialise in the city; no United players live near Merseyside. You don’t see neon signs offering ‘quality perms’ in Manchester.

Liverpudlians seem more maudlin, with the popularity of the deceased measured by the number of tributes taken out in the bulging obits column of the Liverpool Echo. Mancunians are more inclined to adopt a harder exterior – and not just to the thousands of Scousers who flood the Trafford Centre, Manchester’s superior concert venues (the Liverpool team booked their Take That tickets for the MEN Arena on the day they came out) or Manchester Airport, now that Scousers look beyond North Wales for their holidays.

Three days after the game at Anfield, I receive a text from the Liverpool fan who sorted me with a ticket for the Kop.

“The lad next to you knew who you were,” he writes. “He couldn’t think where he had seen you but he clicked after the game. He’d seen you covering Wrexham vs Chester for FourFourTwo last year and knew you were a Manc. He told the others after you’d gone.”

It wasn’t just Manchester United who got lucky at Anfield...

NEXT: The view from The Kop, by Peter Hooton

A View From The Kop

By Peter Hooton, Anfield season-ticket holder

I have an admission to make: I do not hate and have never hated Manchester United. George Bernard Shaw wrote that “Hatred is the coward’s revenge for being intimidated,” and I have never been intimidated by the propaganda machine of England’s second most successful club.

Instead I have been amused and bemused by United’s hatred of all things Liverpool, an enmity based on which club is the biggest/most famous/most successful. Easy: they have the biggest ground, we are the most successful – you’d have to ask an Eskimo which club is the most famous.

The bitterness is a modern phenomenon. As a Liverpool season-ticket holder since the 1950s notes: “Rivalry did exist before the ’70s but it was a healthy rivalry, devoid of hatred.” Indeed, a 1966 poll in supporters’ magazine The Kop named Matt Busby as captain of an all-time Liverpool team. Times have changed.

The trip to Old Trafford was a birthday treat from my dad. It was September 1973, the season United went down. Bill Shankly’s second great team were the champions, whereas United were a club in turmoil. Before kick-off, hundreds of tartan-clad Stretford Enders resembling an army of Bay City Rollers invaded the pitch to attack Liverpool fans in the Scoreboard End. For a wide-eyed youngster, the age of innocence was dead. Now I knew what this fixture meant to United fans: jealousy and pure unadulterated hatred.

As Liverpool FC continued to collect trophies, their loathing increased accordingly. Little did they know that this would be the start of 20 years of domestic and European dominance for Liverpool and a similar period of humiliation and false dawns for the self-styled most glamorous club in England.

This period explains why United fans are so obsessed with Liverpool FC and relentlessly sing about Scousers. Liverpool’s main rivals during the ’70s and ’80s were Leeds, Forest, Arsenal, Ipswich and Everton. Apart from the odd cup, United weren’t on the radar.

Mancunians, though, are used to jealousy. In the 1960s, Liverpool spawned the Beatles and shaped popular culture worldwide while Manchester danced awkwardly to Freddie and the Dreamers. What about The Hollies? Like ‘uber-Manc’ Gary Neville, most actually came from small mill towns around Manchester.

Municipal rivalry started before Beatlemania, but I don’t buy this revisionist Ship Canal vs Docks nonsense. If that’s so, why don’t United hate Everton or Liverpool hate Man City?

In the 19th century Liverpool had sea-shanties, bustling docksides, clipper ships and the romance of the sea. Manchester had dark satanic mills, black pudding, Morris dancers and clogs. Now, it’s a damp, ugly industrial city with no discernable landmarks apart from the mushrooming Old Trafford and hideous Trafford Centre. Liverpool’s landmarks are world-famous: the World Heritage-status Liverpool Waterfront, two magnificent cathedrals, St George’s Hall, the Walker Art Gallery, the Albert Dock and the highest number of listed buildings outside London.

Liverpool fans believe that the club’s achievements have never received the credit they deserve, whereas United’s success since the ’90s has been totally overstated. The ‘Theatre of Dreams’ tag and the Hollywood-style film premiere of their 1999 season documentary Beyond the Promised Land are two examples of their conspicuous vulgarity and red-carpeted arrogance.

After years of denial, Liverpool fans gave United grudging respect for their comeback against Juventus in the 1999 Champions League semi-final. But throughout their success United were bad losers and even worse, bad winners. Liverpool may have had an air of superiority, but they were never as universally despised as United.

The late victory against Bayern Munich in the Nou Camp prompted United fans to repeat that ‘The Champions League is harder to win than the old European Cup’ – a phone-in/fanzine mantra conveniently dropped when Rafa Benitez led Liverpool to a fifth European triumph. United fans even had to fold away the ‘You’re not famous anymore’ banner into the attic.

That hurt them, because for all their domestic success, United have never dominated Europe like Liverpool, Real Madrid, Milan, Bayern and Ajax have in the past. They might be able to attract 76,000 to Old Trafford and spend £30m on a player but you can’t buy European success. That’s why they’re stuck on two European Cups, like Porto and Forest.

That fifth European Cup has silenced the idea that Liverpool are living in the past. At Anfield this year, Alex Ferguson paid Liverpool the ultimate compliment of coming for a goalless draw, something he hadn’t done for years. United know that with Rafa and new investment, Liverpool will again be a force.

That’s why they sing about Liverpool all the time. At Middlesbrough in the FA Cup, it took 30 seconds before they started singing anti-Scouse songs; unless we’re playing United, they’re never mentioned.

Their infatuation reveals a deep-rooted inferiority complex. It’s a cry for help: they really want to be Scousers, evidenced by their adulation of Rooney. As the Romans said, ‘They hate whom they fear.’

Of course Liverpool fans are concerned that United are closing in on our 18 League titles but we’re confident that United will never reach five European Cups before the ice caps melt. As the flag stated after Istanbul: ‘Fergie, we’re back on our f**kin’ perch!’

Andy Mitten is Editor at Large of FourFourTwo, interviewing the likes of Lionel Messi, Eric Cantona, Sir Alex Ferguson and Diego Maradona for the magazine. He also founded and is editor of United We Stand, the Manchester United fanzine, and contributes to a number of publications, including GQ, the BBC and The Athletic.