The Player: Why captains are still important in today's game

Our mole says it’s hard for a manager to drop his skipper – and some don’t have the minerals

The Player has spent 15 years across all four divisions. He’s played in the Premier League and for his country. (Illustration by Spencer Wilson.)

Each week we'll bring you a column from our mole...

Our captain and best player wasn’t performing well. His form reflected that of the team and we struggled at the wrong end of the Premier League table.

Almost every player found himself dropped at one point as the manager tried to find a winning XI. He hoped that dropping someone would give them a kick up the backside, or take them out of the firing line of the media or fans, or send a warning to the rest of the team that none of us were undroppable.

Yet one was. The captain. He’d built up a deserved reputation as our best player, yet for three months he clearly wasn’t. The other players began to mutter about the sacred cow, the blue-eyed boy who could do no wrong. They didn’t say anything to the captain’s face, nor to the manager. Footballers can be quite feckless and it can take an argument to force a long-standing issue to a head, usually in the dressing room after a bad performance. That’s when emotions are most heated.

Handling key

The manager tried to spin it that he was showing he could leave out the captain if he wished, but none of us bought that

Players build up little power bases within a team – cliques, if you like – and they do that through private conversations. Little dirty laundry is washed in the dressing room after training. Footballers have varying opinions on team selection, but almost all feel a team should be chosen on merit. There’s a consensus as to who merits a place. And the captain didn’t.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

The manager usually named his side the day before the match, when he’d play a first-team against a group of fringe or reserve players, who wore bibs. If you got a bib, you weren’t starting. Players dreaded a bib.

One Friday morning, much to our surprise, the captain was handed a bib. His face fell – he looked like he was going to cry. The manager looked just as uncomfortable. He couldn’t bear to see it and 15 minutes into the practice game, he told the captain to give his bib to an opposing player. The captain wasn’t dropped.

The manager tried to spin it that he was showing he could leave out the captain if he wished, but none of us bought that. Instead, he looked like he didn’t have the courage to carry through his decision that the captain wasn’t worth his place in the side. The players spoke about little else after training. At a time when the manager should have been motivating us, he did the exact opposite. We lost the following day.

Clash of personalities

When Sir Alex Ferguson dropped Wayne Rooney it led to one of Manchester United’s best players wanting to leave, whatever he’s said since

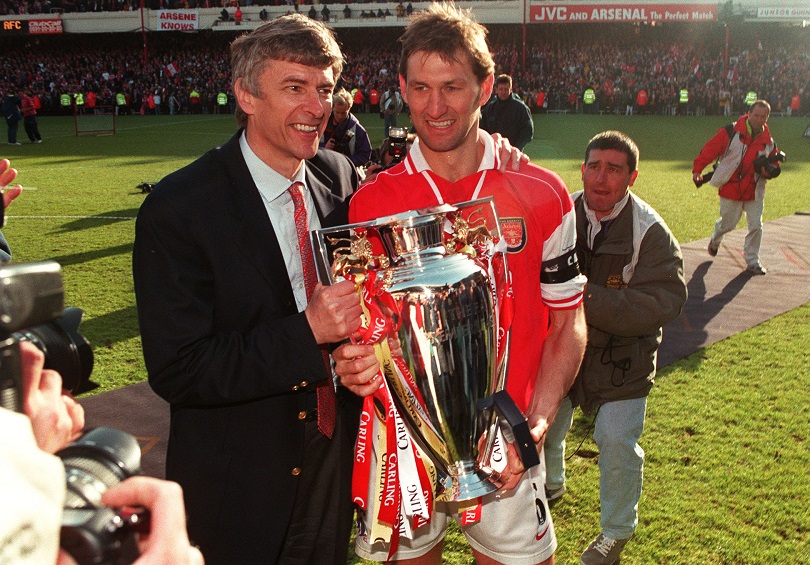

His actions were typical of most managers I’ve worked with. The best would drop any player, but they need to feel ultra-confident of their position. Think Jose Mourinho and Iker Casillas, benched despite being worshipped as skipper and icon for club and country.

But it’s not easy. When Sir Alex Ferguson dropped Wayne Rooney it led to one of Manchester United’s best players wanting to leave. Big players usually have big egos. There’s room for a few of those if they’re on the same side, as a manager and player should be, but not when there’s disagreement between the two. The best captain should be the manager’s lieutenant on the field, not an enemy in the shadows.

Most managers hope the problem of a star playing poorly will sort itself out. They are reluctant to drop him because a) they don’t have the balls; b) he’s usually very good; c) they don’t want to lose his support; d) they don’t want a miserable star in the dressing room when he’s probably more popular than the manager; and e) they hope he’ll play his way out of the bad patch. I’ve been through plenty of poor spells when my confidence was low, and I can recall Manchester United fans booing Ryan Giggs for a while.

Assistant steps up

I have sympathy for a manager, though, because they’re damned if they do and damned if they don’t. Had Manchester City persisted with Joe Hart, it would have shown the team they wouldn’t be dropped even if standards fell. Also, more mistakes can mean more bad results and bad results lose managers their job.

There’s no point in the two parties having direct contact, as their emotions will be too raw and time will be needed for the player to step back and maybe realise the boss has a point

Yet in dropping him, Hart won’t thank Pellegrini. It’s at times like this that a good assistant manager can come to the fore by trying to improve relations. There’s no point in the two parties having direct contact, as their emotions will be too raw and time will be needed for the player to step back and maybe realise the boss has a point. In the meantime, an assistant will assure the player that the gaffer still rates him (if he does) and that he will get his chance when he deserves it.

And our captain? He outlasted the manager who wouldn’t drop him.