When Portsmouth’s 6.57 Crew tried to hijack the general election – and accidentally helped the Tories win

Docker Hughes’s notorious firm were better known for causing chaos wherever they went in the 1980s, but made headlines of a different kind when their leader ran for office with a madcap manifesto

“I suppose Marty wasn’t your average election candidate,” says Mark Dewing, the founder of one of British politics’ most short-lived parties. “In fact, I’m not too sure he would have recognised Maggie Thatcher if you’d shoved a picture of her in his face.”

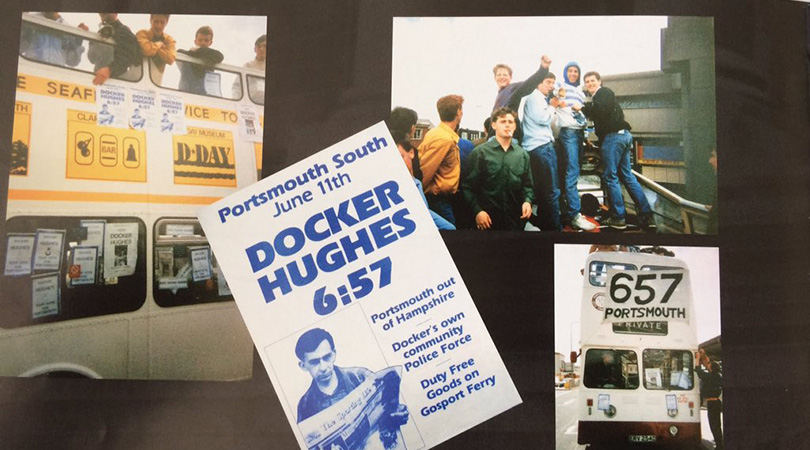

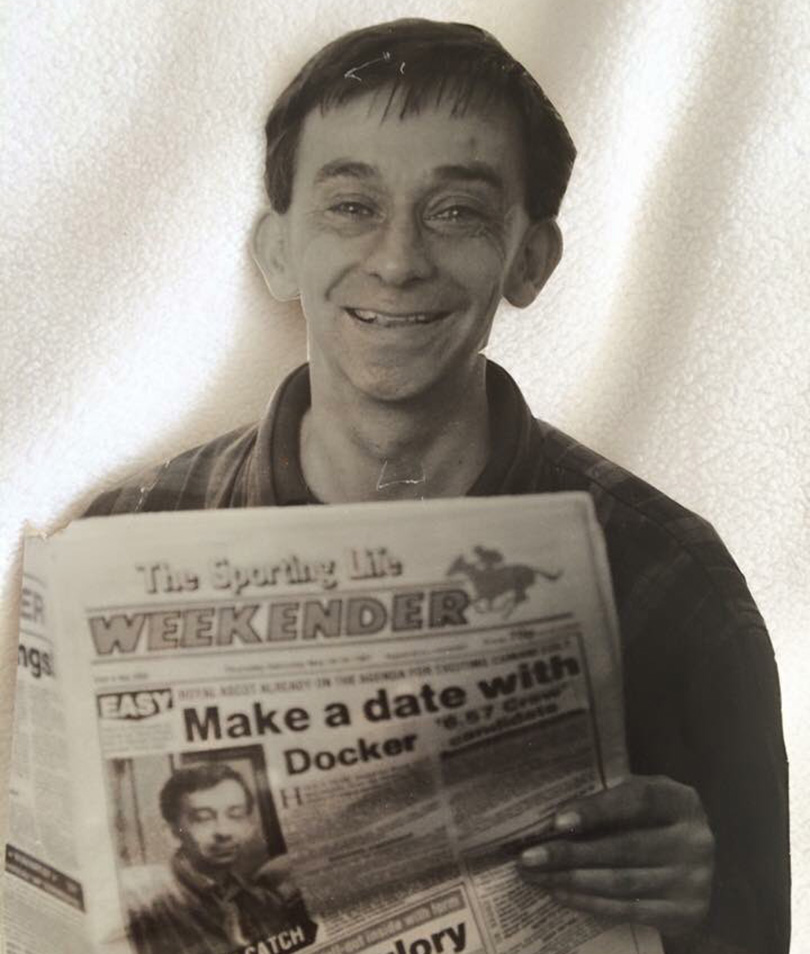

In the South Portsmouth constituency in summer 1987, though, that didn’t matter. He might have been short on intellect and general knowledge but, with the backing of Portsmouth’s infamous 6.57 Crew (a name apparently derived from the time of the first train up to London on a Saturday), Marty ‘Docker’ Hughes was suddenly the man that everyone was talking about.

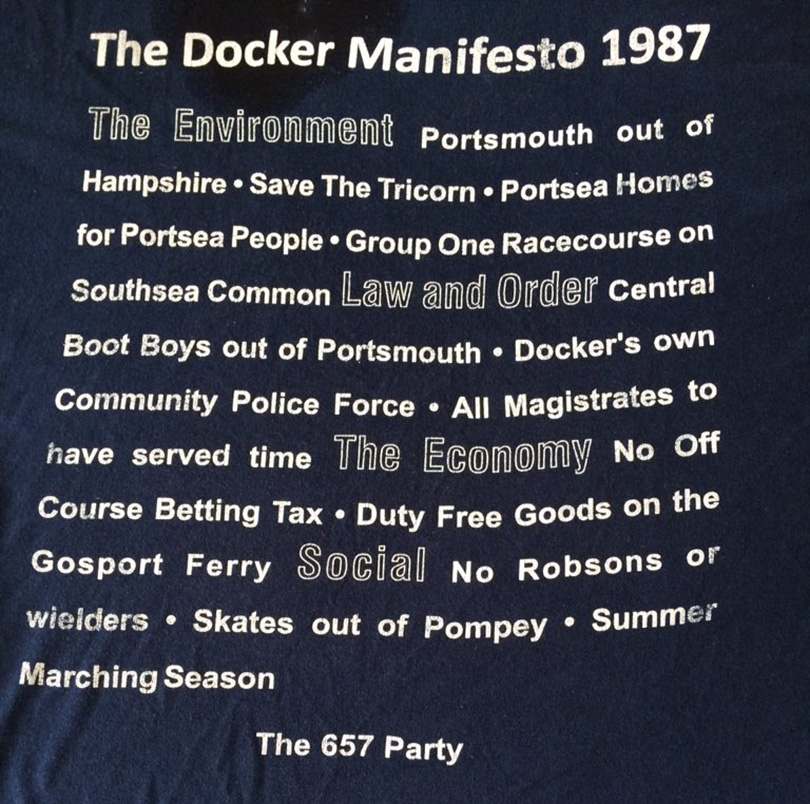

Armed with a manifesto that promised duty free booze on the Gosport ferry, getting Portsmouth out of Hampshire, employing only magistrates who had done a stretch behind bars and scrapping off-course betting tax, Hughes promised revolution in a city beset by high unemployment and massive distrust between supporters and a local police force that had long grown tired of their antics.

“That was the motivation behind it, really,” says Dewing. “We hated the police and they hated us. We just sat down one night and talked about how we could really get one over on them. Someone mentioned the general election and that was that. Marty was the perfect candidate.

“We marched off to the council offices from the pub that we used as our base the next morning, paid our £500 deposit and signed him up there and then. As soon as we did, all hell broke loose.”

From the bar of the Sir Robert Peel – a pub which was demolished in 2004 – Hughes’s ‘campaign team’ were soon fielding calls from the nation’s media. TV crews descended for interviews with a candidate who made Screaming Lord Sutch look like a political heavyweight.

There was just one problem.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

“Marty was a man of few words,” says Dewing. “We played five-a-side football at the Somerstown Estate in Pompey on a weeknight, and TV South turned up to try to get a word with Marty one night. We locked him in a cupboard in the changing rooms until they’d gone. When he finally got out we were waiting outside and pelted him with footballs.”

He might not have been much of a conversationalist but that didn’t stop the political establishment from spouting off over his candidacy. Thatcher herself said that Hughes standing in the election was ‘a rubbish idea’. Her stance was hardly surprising given her outright enmity towards footballers supporters throughout her time as PM.

Neil Kinnock, the Cardiff City-supporting leader of the Labour party at the time, suggested that the government should intervene to ensure that Hughes wasn’t allowed to stand and potentially divert votes away from the major parties. They were strangely prescient sentiments given what eventually transpired.

And the police? Well let’s just say that Hughes’s appearance on the ballot paper did little to reduce simmering tensions between supporters and the local constabulary.

“We just couldn’t believe what we were hearing and seeing,” says Dewing. “We had the country’s top politicians giving their opinion on whether Marty should be standing for election, then the police were wading in telling anyone who would listen that it was a shit idea.

“The whole thing was just bonkers. Even before the election we had achieved everything that we set out to achieve. Marty had barely needed to open his mouth.”

Hughes and his mates even managed to hire a bus from a local company so they could spread his message across the city. That tour took them past the Tricorn Centre – a building so grotesque it was once voted the third-ugliest in Europe. Making sure it was preserved was another of Hughes’s election promises.

As June 11 drew near, Hughes’s rivals for the election – namely Michael Hancock of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) and Tory candidate David Martin – harboured genuine concerns that any protest vote for the 657 party could have a direct bearing on a seat won by the SDP in a by-election three years before.

That, though, was the least of Hughes’s concerns – his pub-based party was revelling in its newfound fame.

“Looking back now, you struggle to believe that we managed to achieve so much in what was basically a three- or four-week campaign,” says Dewing. “We had t-shirts printed, the manifesto was everywhere you went in Portsmouth and we had the prime minister talking about us. What wasn’t to love?”

On the night of the election, only 30 members of any party were allowed in the counting hall as the votes were totted up. There were another 200 people outside, the majority having walked directly from the Sir Robert Peel, well-oiled, to the Portsmouth Guildhall.

“I don’t think anyone there knew what to make of us but the atmosphere was amazing,” says Dewing. “It was absolutely electric inside the hall and outside too.”

The pub was boarded up and subsequently demolished in 2004.

It was early morning by the time the votes had been cast in an election that would ultimately be won by the Tories with a reduced majority. With Docker periodically dropping off to sleep on stage, following a warning about his behaviour from the police, the counting of 76,292 Portsmouth South votes was finally completed.

And the leading parties’ worst fears were about to be realised.

Just 205 votes separated Hancock and Martin, with the Tories wrestling the seat from the SDP after two recounts. Hughes polled 455 votes, bringing him tantalisingly close to 1% of the constituency’s vote.

Looking gaunt through a lack of shut-eye and a few too many sherbets in the warm-up, the diminutive and unlikely political wannabe addressed the crowd as the Tories celebrated.

“I would like to thank all the supporters who have come out to vote for us tonight,” he said, to cheers from 15 members of the 657 party who’d forsaken sleep and remained in the hall. He then, to the surprise of his mates and also the Portsmouth police force, added that he hoped they would vote for him “in the future”.

As it was, the 657 party would never run again.

Docker Hughes died in his mid-30s in the summer of 1992. Quite what he'd be making of the UK's current political landscape is anyone's guess – but he'd probably be raising a glass to it in some way.

THEN READ...

STORY The best thing you'll ever read about Millwall

WHAT'S IT LIKE TO... Have your entire life ruined by injuries?