Portuguese men o' war: why Benfica vs Sporting is more than a game

When Eagles meet Lizards, there's plenty of venom but rarely violence at Lisbon's fiercest derby. For the December 2008 issue of FourFourTwo, Sergio Krithinas went along to experience it first hand...

“We will eat them,” yells a Benfica fan standing outside a food van next to the Stadium of Light – and he’s not talking about the burgers.

It’s three hours before the big game in Lisbon and ‘them’ are Lagartos, ‘The Lizards’, the nickname given to Sporting fans due to their green-and-white striped kit.

Other jokes and comments fly through the air: one Benfica fan shouts out “Anything less than a 3-0 win will feel like a loss for us,” while another promises to shave the head of Sporting coach Paulo Bento, on account of his latest dodgy hairdo. On the whole, though, here in the Alto dos Moinhos area of the city, the mood is quiet and respectful. Fans seem more interested in their pre-match ritual, eating a pig-skin sandwich, the coirato, and sipping a small bottle of beer, known as a mini.

As the tension grows, the chants become more venomous. “Benfica is crap, Benfica is crap,” sing half of the group, while the other half proclaim, “The hooker, the hooker, the hooker is your mother...”

Benfica and Sporting have hated each other for the last 100 years, but theirs is a unique kind of hate, a Portuguese way of hating, typical of the country whose military-led pro-democratic coup d’etat in 1974 was nicknamed the Carnation Revolution because of its lack of violence.

In the hours before this, the first derby of the season, both sets of supporters share the areas around the stadium peacefully. The Benfica fans are in the vast majority and their strength in numbers gives them the confidence to start the chants. “SLB, SLB, SLB… Glorious SLB, Glorious SLB!” is their anthem.

The Sporting fans walk by, seemingly indifferent, but make no mistake: getting one over on Lampioes, ‘The Lamps’ – a nickname given to Benfica fans because their home ground is the Stadium of Light – is all that occupies their minds.

This tranquil picture dramatically changes following the arrival of Sporting’s biggest ultra group, the 2,400-strong Juve Leo, who have walked the one mile from their own Jose Alvalade Stadium to get here. Many are wearing T-shirts bearing a pig’s face and the slogan: ‘Lampioes? No, thank you!'

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

As the tension grows, the chants become more venomous. “Benfica is crap, Benfica is crap,” sing half of the group, while the other half proclaim, “The hooker, the hooker, the hooker is your mother...”

The large police presence quickly becomes visible and the ultras are swiftly shepherded into the stadium. A small scuffle breaks out, and three fans are arrested for throwing stones at the police. As usual, though, there is very little violence: once again, the Portuguese fans prefer carnations to fists.

Make peace, not war

You don’t find much physical hostility between fans in this corner of south-western Europe, as the history of clashes between these two sides demonstrates. The hatred is intense, but only once has it spilled over into tragedy, when Benfica’s ultras, celebrating their first goal in the 1996 Portuguese Cup Final, hurled a fire-cracker into the stand where the Sporting fans were gathered.

It landed on Rui Mendes, a 36-year-old father of two, and gored his chest. He died instantly. Sporting fans shouted, “Killers, killers!” at the Benfica fans, but astonishingly the game continued. Benfica went on to win 3-1, but their celebrations were quickly replaced by mourning which, briefly, united the city and its two biggest teams. The man who hurled the missile, Hugo Inacio, was given a four-year jail sentence.

One of Portugal’s most famous authors, Antonio Lobo Antunes, explains that Benfica’s history is more steeped in keeping peace than causing violence: “I served in the war with Angola in the 1960s and I saw some extraordinary things. When Benfica played, we switched on the radio, turned the speakers towards the woods, and we were never attacked. Even the MPLA [the Angolan party fighting for independence] supported Benfica.

I can understand that you would shoot a Porto fan, but how could you do it to a Benfica fan? Does it ever make any sense to shoot a Benfica fan?

"It made the war very strange: it didn't seem to make sense to want to fight people that supported the same club as us. It’s true, Benfica was our best protector in the war: [the ceasefire] never happened when Porto or Sporting played. I can understand that you would shoot a Porto fan, but how could you do it to a Benfica fan? Does it ever make any sense to shoot a Benfica fan?”

Like so many rivalries, the distinctions between Sport Lisboa e Benfica and Sporting Clube de Portugal has its genesis in class. Sport Lisboa was founded on February 28, 1904 by a group of students who added the name Benfica in 1908. The club was poor and always struggled to provide their athletes with the best conditions.

Sporting, founded on July 1, 1906, was immediately bankrolled by the grandfather of their founder, Jose de Alvalade, who happened to be a viscount. “Sporting is a more elitist club, and they are run in a very particular way,” says Joao Pinto, one of the best Portuguese players to have represented both teams. “Benfica are the biggest club in Portugal, they are more ‘the people’s club’ with a huge fanbase, and therefore their expectations are always more demanding.”

Benfica’s directors claim that they have the biggest number of card-carrying members in the world. Their entry in the Guinness Book of World Records cites over 170,000 registered members, many of them from the city’s lower classes, much to the amusement of their rivals. “When the Stadium of Light is full, there are 65,000 teeth in there: one for each of their fans” is the popular gag among their rivals.

The class difference was apparent before the first meeting between the two teams on December 1, 1907. Sporting are alleged to have signed (or stolen, if a Benfica fan is telling you the story) eight players from their rivals, after offering them better pitches to practice on and, the clincher, warm showers after the games.

That game was played in torrential rain, at Quinta Nova, Sport Lisboa’s ground. At half-time, Sporting emphasised the gulf between the teams by providing their players with fresh shirts to replace their dirty ones. They won 2-1 and Sporting’s sartorial influence was once again apparent on July 18, 1911 when their players refused to welcome Benfica to their stadium, saying their scruffy opponents were not fit to appear on their hallowed pitch.

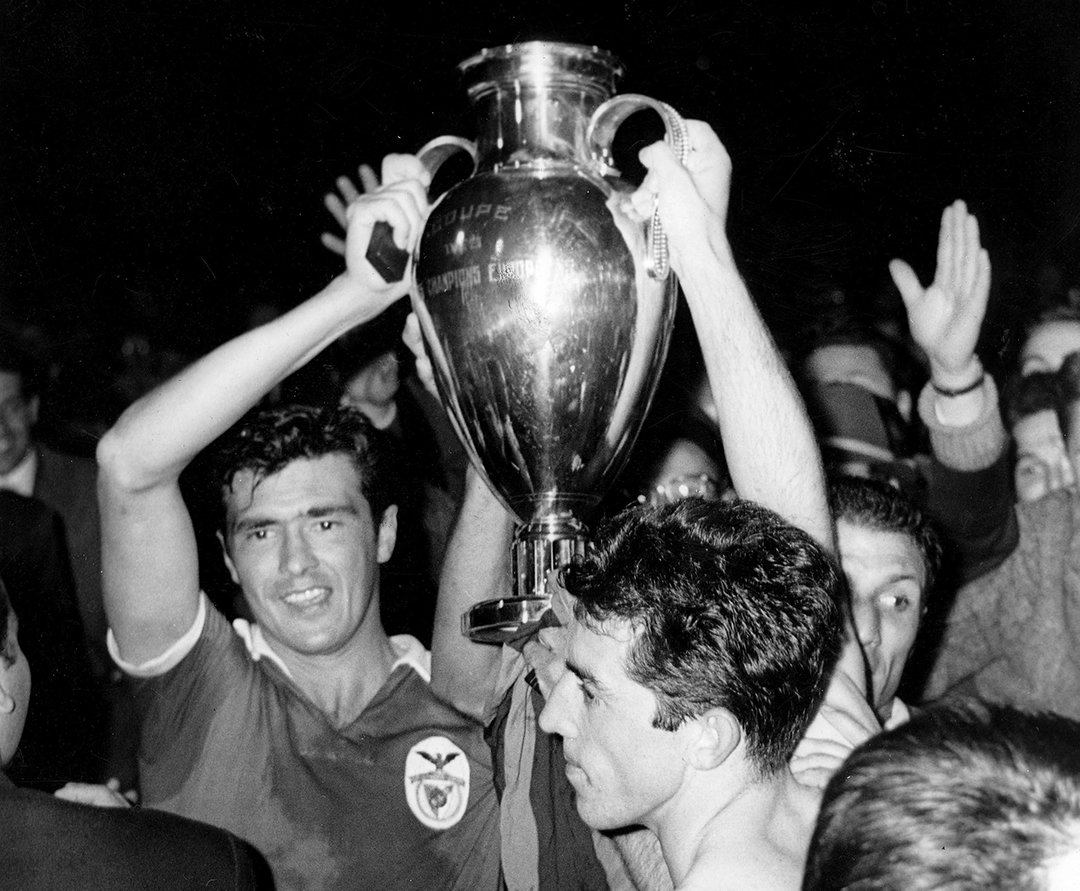

Despite losing those early encounters, history has more often smiled on Benfica: in 352 games, including friendlies, the Reds have won 151, drawn 66 and lost 135. They’re also ahead in the honours stakes, having won 31 league titles to Sporting’s 18 and 24 Portuguese Cups to Sporting’s 19. Benfica have also won the European Cup twice, finishing runners-up a further five times. Sporting have just the 1964 Cup Winners’ Cup to show for their European exploits.

And yet for this match, the first official derby of the season, Sporting are the favourites. It’s round four of the league and the visitors have won their first three matches of the season, and also beat Benfica 2-0 in an August friendly. It’s the first real test for Benfica’s new Spanish coach, Quique Sanchez Flores, after a disappointing start to the season: his side drew two of their first three league matches and lost a UEFA Cup tie to Napoli.

The pre-match press conferences have passed with a few niggles, with Sanchez Flores suggesting some irritation with his opposite number Paulo Bento. “I’m a humble guy and I don’t like to open out my chest and talk big,” he said in response to Bento’s simple observation that “Sporting haven’t lost on their last three trips to the Stadium of Light”. But the pressure is mounting: defeat will leave Benfica seven points behind their rivals after only four games.

NEXT: The Black Pearl and Benfica's dominance

The Black Pearl

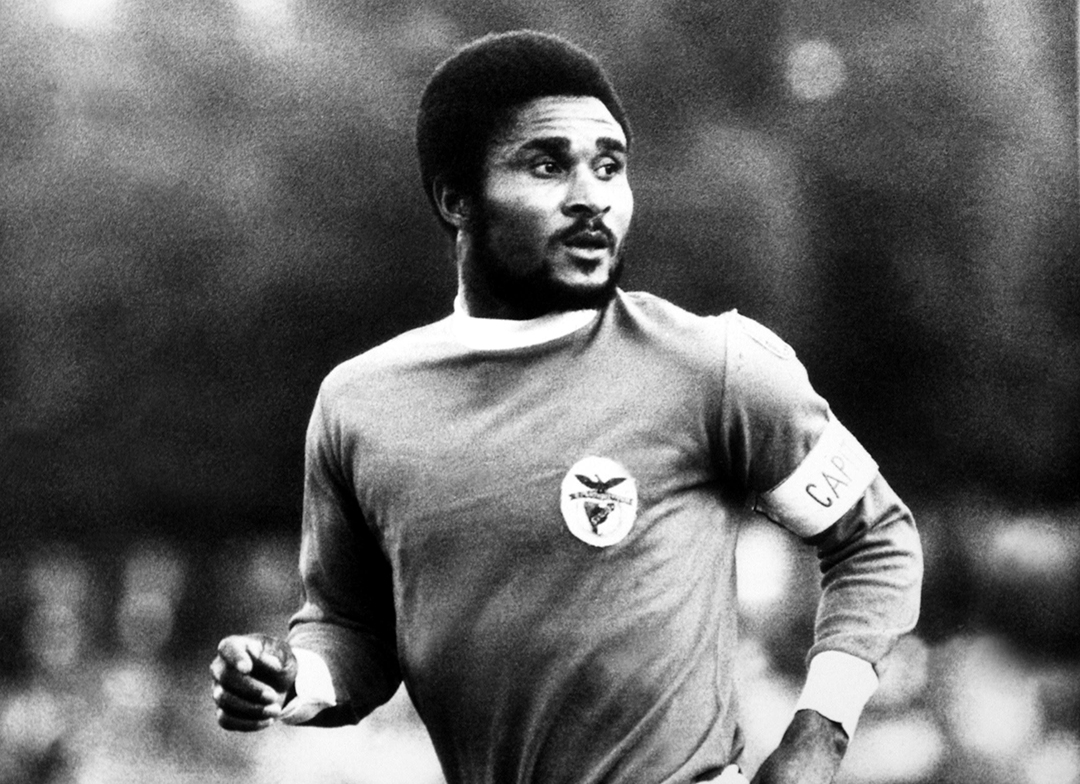

Benfica’s dominance over Sporting really started in the 1960s, when the Eagles – Benfica’s nickname for themselves – had Eusebio on their books. Arguably Portugal’s greatest ever player, ‘The Black Pearl’ originally played for Sporting de Lourenco Marques, Sporting’s nursery club in Mozambique, but in 1961, Benfica ended up signing him after convincing his mother that they were the better club for her little boy.

Benfica offered me a professional contract and Sporting wanted me to do some trials with their reserve team. So my mother signed the contracts with Benfica

Sporting fans still claim that Benfica stole Eusebio with the help of the fascist police, who allegedly sped through the paperwork. “All lies,” Eusebio tells FourFourTwo. “I never understood where that story came from. Benfica offered me a professional contract and Sporting wanted me to do some trials with their reserve team. So my mother signed the contracts with Benfica. Later, someone at Sporting must have made up that story to explain why they failed to sign me.”

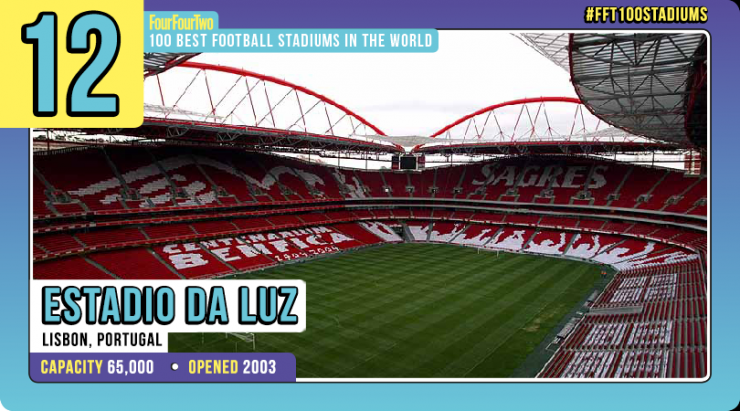

Sporting had been the more successful until Eusebio came along. Benfica’s early days were characterised by financial struggles and regular stadium changes. In 1952, their problem was solved when fans got together and helped to build ‘Estadio da Luz’ – translated as the Stadium of Light and named after the area of Lisbon that Benfica call home – a project that was completed in 1954. Finally, Benfica could now compete with their neighbours.

Their stadia are just a mile apart and connected by one of Lisbon’s most important roads, the Segunda Circular. Both were inaugurated in 2003, shortly before Euro 2004, and became the butt of mutual jokes. “Our stadium has just one problem: the toilets are a mile away,” say Benfica fans, while the Sporting fans, referring to the concrete walls that surround the the Stadium of Light, respond: “The Benfica stadium will be fantastic... when they eventually finish building it.”

Sporting's revenge

It took just over 30 years, but Sporting eventually took their revenge for the Eusebio saga. It was 1993, and with Benfica again struggling financially, Sporting swooped to sign Antonio Pacheco and Paulo Sousa, two of the most promising players in Portugal.

It could have been worse: Benfica wonderkid Joao Pinto was close to moving as well, and even sent a fax asking to be released from his contract because he had not been paid, but someone smart at Benfica unplugged their fax machine so they never received his request.

The club’s directors also took the player to Spain to keep him away from any Sporting temptation. It was a trip worth taking: Joao Pinto stayed and was crucial in helping Benfica win the league that season, even scoring a hat-trick in the 6-3 win at Sporting that clinched the title.

And yet in summer 2000, Sporting finally got their man. Just before Euro 2000, Joao Pinto moved across the city, and two years later, helped his new side win the Portuguese league. “I never expected to be made to feel so welcome by the Sporting fans,” he admitted.

There were some tough times. I was chased by some fans and got through some pretty tricky situations. I never had police protection or bodyguards: it was more a case of people simply having different opinions

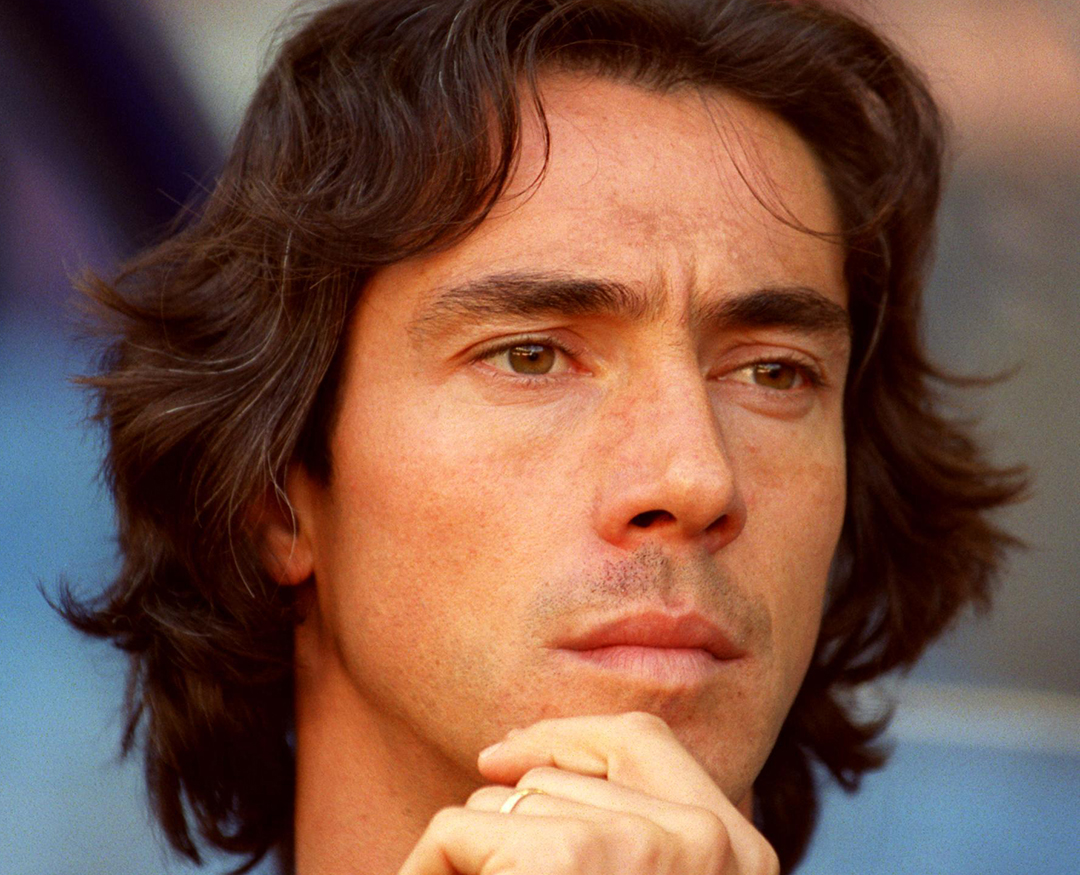

Paulo Sousa had helped Benfica win the league title in 1991 and the Portuguese Cup in 1993 before moving to Sporting. He was the number one hate figure in the Stadium of Light clash played under tragic circumstances, as a recent car accident had left Sporting’s Sergey Cherbakov forever confined to a wheelchair.

“There were some tough times,” Sousa tells FourFourTwo. “I was chased by some fans and got through some pretty tricky situations. I never had police protection or bodyguards: it was more a case of people simply having different opinions.”

Sousa chatted with his former team-mates in the tunnel before the game, and was relieved that board members and former youth-team coaches all greeted him like an old friend.

“There was no tension there at all,” he says. “It was built up by the press probably to rile the fans. It was said that objects were thrown onto the pitch at me, but I was playing in the middle and nothing hit me. I just tried to focus on the game.” Now, Sousa prefers not to have to choose between the two sides, and instead claims he supports Portugal. “The national team is my club,” he says with a smile.

NEXT: "I'd rather see a Benfica defeat than a Sporting win"

It's all gone quiet over there

Back in the Stadium of Light, the big-game atmosphere has fallen flat. The stadium goes quiet soon after the traditional flight of the Benfica Eagle, as Sporting take control of the game early on. The Juve Leo may be in the minority, but they are out-singing the hosts as their optimism grows. You can hardly hear the biggest Benfica ultra groups, the No-Name Boys or the Diabos Vermelhos, Red Devils.

Sporting’s Yannick Djalo misses a clear chance in the first minute with only goalkeeper Quim to beat, but Benfica’s fans rise as one when Oscar Cardozo tries his luck from distance, before Nuno Gomes somehow misses from two yards out.

Referee Duarte Gomes comes in for regular stick from the home fans, who haven’t forgotten the penalty he awarded Sporting in April 2002 after Mario Jardel dived to earn a last-minute equaliser. When Helder Postiga looks to have fouled Benfica’s Yebda in the area, the penalty screams engulf the arena. Gomes waves play on, and the tension mounts.

It’s a tight game, but on 68 minutes, the deadlock is broken: former Arsenal winger Jose Antonio Reyes hits a left-footed shot from outside the area which flies past Sporting goalkeeper Rui Patricio. Four minutes later, Benfica double the lead, Sidnei converting Carlos Martins’s cross to make it 2-0.

Martins, more than anyone else, celebrates the goal as if it’s the winner in the Champions League final: the Juve Leo had singled him out for abuse in the first half, and during corner-kicks had hurled objects at him (failing both times, as a lighter and a ham sandwich end up striking the pitchside photographers).

The home fans finally find their voice: “SLB, SLB, SLB… Glorious SLB, Glorious SLB!” goes the chant, as the majority of the 60,022 crowd stamp their feet and create the fearsome atmosphere that was so lacking early on. The stadium feels ready to explode.

The post-mortem among Benfica fans conveniently forgets the early stages of the game, instead focusing on the overlooked penalty appeal. Sports director Rui Costa is fined €200 for criticising referee Gomes at half-time. The newspapers agree that Benfica’s three points are deserved. “Actually, I’m a bit upset with Quique because he didn’t give me any moments of concern, there was no shot against the post, nothing,” writes Portuguese satirist Ricardo Araujo Pereira. “It was the calmest last 15 minutes I ever had in a derby.”

It ain't like the good old days

While Benfica fans wallow in today’s victory, Sporting’s have to reminisce about past triumphs, like their biggest ever win against Benfica, in December 1986.

“I was on the Sporting board during that period and I turned up to that match in a red shirt,” recalls lawyer Dias Ferreira, who represents Sporting on the chat shows that dominate the Portuguese sports channels. “The Benfica president saw I was wearing his team’s colours and said I looked like I was going to sign for them. I told him it was a lucky shirt and it was. We won 7-1.”

Ferreira plays up to his anti-Benfica persona – “I tell people I would rather see a Benfica defeat than a Sporting win,” he says – but the Reds fans seem to have a grudging respect for him. “They say they like what I say and wish I supported their team.”

The one exception is Benfica president Jose Vieira, who has sued Ferreira for defamation, and been sued by him. Their row began when Ferreira doubted the legality of a venue-change for Benfica’s 2005 match against Estoril in the season they won their first title for 11 years. Vieira is alleged to have called him “a gangster” and a court case will ensue.

Pereira, you could say, is the Benfica equivalent of Ferreira. The comedian, famous for his routines as part of comedy-group Gato Fedoronto, meaning ‘Smelly Cat’, travels home and away, and abroad, for Benfica matches. “The derby is the happiest day of the year for me. Even if we lose, the hours beforehand are just so exciting,” he says.

Pereira’s greatest moment supporting Benfica came last season, after his side were knocked out of the Portuguese Cup following a 5-3 defeat to Sporting. The TV cameras focused in on his miserable face after the match, while in a corner of the screen, Benfica boss Fernando Chalana was being interviewed.

“At that moment, when I was taking up the main screen and Chalana was in the small box in the corner, I felt that I had become a symbol of Benfica. I had achieved my life’s objective. I could now die happy – and after that result, that’s actually what I wanted then.”

Paulo Sousa admits that he has played in cities where the intensity of the derbies is more intense. “The biggest was in Greece between Panathinaikos and Olympiacos,” he says.

“It was always very emotional, and very problematic, both before and after the game. In Milan, the derby there was also intense. I was at Borussia Dortmund and in Germany, the derbies were quieter although they were big games. It’s just a matter of culture.

"We all know that the fans behave according to their emotional state of mind, whether they have concerns about their jobs or their families. But they are influenced by what they read, what they hear. Fortunately, I think that the press is better behaved in how they build up the game and then how they present it – not only in Portugal, but across Europe.”

But any thoughts that this rivalry is not a serious one can be banished following the comments of football commentator and journalist Rui Santos, who launched a debate on his Sunday chat show Tempo Extra, ‘Extra-Time’, on SIC calling for a merger between the two clubs.

The reason Portuguese football has so many financial problems is because people make decisions based on their hearts and not their heads: it’s all about passion but no rational thought

“I know they refuse to share the same stadium but that has been proved to be the best solution for teams,” he said. “The reason Portuguese football has so many financial problems is because people make decisions based on their hearts and not their heads: it’s all about passion but no rational thought. I truly believe that football can’t survive without a bit more rationalisation.”

The phone-lines were jammed as furious fans of both clubs called to criticise him. Some fans who were wearing masks even tried to assault him as he left the studios one night.

“I knew there would be negative reactions to this,” Santos responds. “But banks are closing all over the world and Portuguese clubs are dependent on their survival. Benfica and Sporting are both on life-support machines at the moment: a merger may seem a bold idea now, but in one year, five years, or 10 years, time will prove that it’s the right thing to do.”

Thankfully for fans of these two great clubs, he seems to be in a minority of one.

This feature first appeared in the December 2008 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe!