Random byes, four-team finals and even easier qualifying: The early days of the Euros

Richard Edwards charts the untidy history of the European Championship...

It says much for the slow-burning nature of the European Championship that the man who first suggested the creation of the tournament was dead by the time the competition finally became a reality.

Had he been around today, it’s unlikely that Henri Delaunay – sporter of a corking moustache and wonderful pair of spectacles – would have featured highly in a list of potential drinking partners for Euro sceptic-at-large Nigel Farage. But the man after whom the tournament is still named remains one of the most visionary European administrators of any era.

It's a shame that his successors didn’t appear capable of organising a hearty drinking session in a Belgian, French, Dutch or German brewery. The original tournament was as long and winding as the whiskers that adorned Delaunay’s French face, and qualification bordered on the farcical.

Messy beginnings

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

The UEFA congress of 1957 in Stockholm had rubber-stamped the notion of a continental competition, but only if a minimum of 16 countries agreed to enter.

That looked some way off as West Germany (then the world champions), Italy and England all took a dim view of a tournament that captured the imagination about as much as the appointment of Jean-Claude Juncker as EU commissioner had earlier this year.

A late rush of entries ensured that magic number was reached, although the two-legged ‘preliminary round’ clash between Ireland and Czechoslovakia kicked off almost a full year after the first qualifying ball was kicked in anger by the USSR against Hungary, in a stadium fittingly named after the revolutionary Vladimir Lenin.

The USSR, the tournament’s inaugural victors, would win that opening match 4-1 on aggregate, although whether anyone could remember the score from the first leg must surely be a moot point: the return leg in Budapest was played 364 days after the first match in Moscow.

To cap a bizarre qualifying campaign, the USSR made it through to the final four after Spain refused to travel to Moscow for their quarter-final match, all courtesy of General Franco’s innate distrust/pathological hatred of left-wingers.

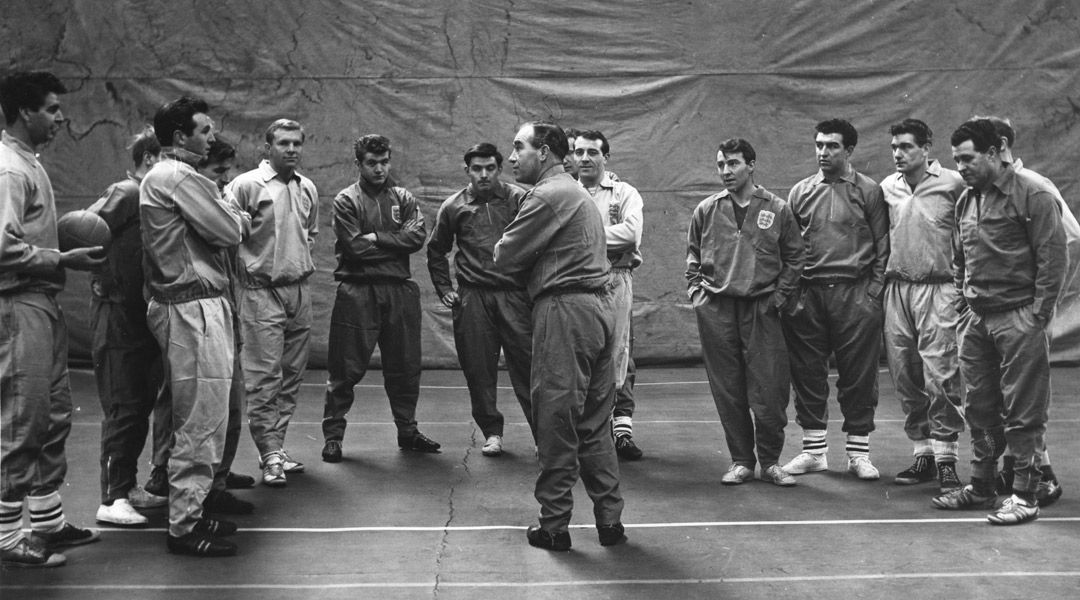

With the competition up and stumbl- er, running, the 1964 edition was the first to feature the home nations, with England, Wales and Northern Ireland all taking part.

There were even signs that UEFA was getting the hang of this qualifying lark, with the preliminary round – necessary to accommodate the 26 countries that had entered – even taking part before the first round of two-legged qualifiers.

For England, entering the tournament was seen as a gateway into a brave new world, following a root-and-branch review of the game after a disappointing World Cup in Chile (ring any bells?).

“The FA will therefore enter in principle and study a memorandum which I have prepared,” said Sir Stanley Rous, then FA honourary secretary and the newly elected president of FIFA in the autumn of 1962.

The English fall-out

It wasn’t long, though, before this brave new world was causing Rous and his fellow FA members a rather large headache. No sooner had their opening qualifier against France been announced than England were squabbling with their friends across the Channel over venues and dates.

“Already, all the brave new plans by the Football Association and the Football League for recasting a new football world within these shores seem to be disintegrating,” wrote The Times' football correspondent.

“Disagreement over the dates for England’s entry into the European Nations’ Cup because of league club demands, and the quibbling over two added international matches to the programme, throw the whole situation back to where it was before Chile and the World Cup. Everything seems to remain as cynical and selfish as it was before.”

England needn’t have worried, with their 1-1 draw against France at Hillsborough in October 1962 swiftly (perhaps the wrong word...) followed by a 5-2 mauling at the Parc des Princes the following February in Sir Alf Ramsey’s first game in charge.

“No time now for any quasi-political comment,” wrote The Times. “This a moment to forget not only in Sheffield but Brussels.”

Still, at least England had tried to reach the tournament’s four-team denouement (this time in Spain); the Scots still hadn’t seen the point of entering.

Keeping it British

Perhaps the high note of qualifying was the performance of plucky little Luxembourg. Bafflingly not required to take part in the preliminary round, they beat the Netherlands – who would be World Cup finalists just over a decade later – in the first round before eventually missing out on the finals after a 1-0 replay defeat to Denmark following a breathless 5-5 aggregate draw.

By the time 1968 rolled around, the European Championship finals were still a four-team affair despite eight qualifying groups being needed to whittle the 31 teams down to the last eight.

In keeping with the home nations cynicism of anything that didn’t resemble fish n’ chips, haggis or leeks, it was decided – not by UEFA, but by the FA itself – that the Home Nations Championship, rather than qualifiers involving teams away from these shores, would provide their passage to the quarter-final stage.

“We have every indication that the European authority will accept this recommendation,” said then FA secretary Denis Follows. If only the home nations carried such clout now.

England – then, of course, the reigning world champions – scraped their way into the last eight, despite the Scots' famous 3-2 Wembley win in April 1967. A 1-1 draw at Hampden Park in front of over 130,000 fans eventually saw Ramsey’s men home.

“If there was anything to be learned from the occasion it was that the reigning world champions cannot in the future afford to dabble in a similar show of brinkmanship,” wrote The Times’ Geoffrey Green.

Rise of the minnows

It was in qualifying for the 1972 tournament – still featuring a final competition unfathomably consisting of four teams – that the qualifying format we now recognise and, let’s be honest, tire of – first came into being.

England were drawn in a group which sent them to Switzerland – their opening opponents in qualifying for Euro 2016 on Monday night – Greece and Malta. The emergence of the latter, alongside Cyprus, signalled the start of the minnows’ invasion of the European game, although San Marino, Liechtenstein, Andorra and the Faroe Islands were still a mere glint in UEFA’s eye.

Fresh from their quarter-final heroics of 1964, Luxembourg appeared intent on consigning that success to history, with a disastrous campaign ending with them plum last in Group 7 (the football alphabet had yet to be invented) and harbouring a goal difference of minus 22.

In keeping with a decade to forget, England flunked qualifying and missed out on the last eight, although finishing below eventual champs Czechoslovakia offered some solace. The Welsh, meanwhile, finally had something to cheer after topping their group to make it through to the final qualifying knockout stage, where they lost, somewhat predictably, to Yugoslavia.

Inflation

With the number of World Cup participants expanding like a field of rabbits on Viagra, UEFA finally doubled the size of the competition in 1980 – although it was still only the top team from each group that progressed.

Only in 1996 did the European Championship expand to 16 teams, in reaction to the increasing number of countries created by the collapse of the USSR and the breaking up of Yugoslavia.

Now, with qualifying for Euro 2016 involving 53 teams and welcoming Gibraltar for the first time, the tournament in France will involve 24 countries. That format might not be to the taste of everyone, but the visionary Delaunay would surely approve.