Remembering Harry Gregg: the Manchester United legend and reluctant hero of Munich

The Northern Irish goalkeeper, who bravely rescued team-mates and passengers following the Munich Air Disaster, has passed away, aged 87

“Harry, you’re my hero and I mean that,” said George Best about Harry Gregg.

“A great athlete and a great man who was a true friend to my father. Harry’s actions (at Munich) sunk in and he continued to rise in my estimation. Bravery is one thing – all goalkeepers must have it – but what Harry did was more than about bravery. It was about goodness.”

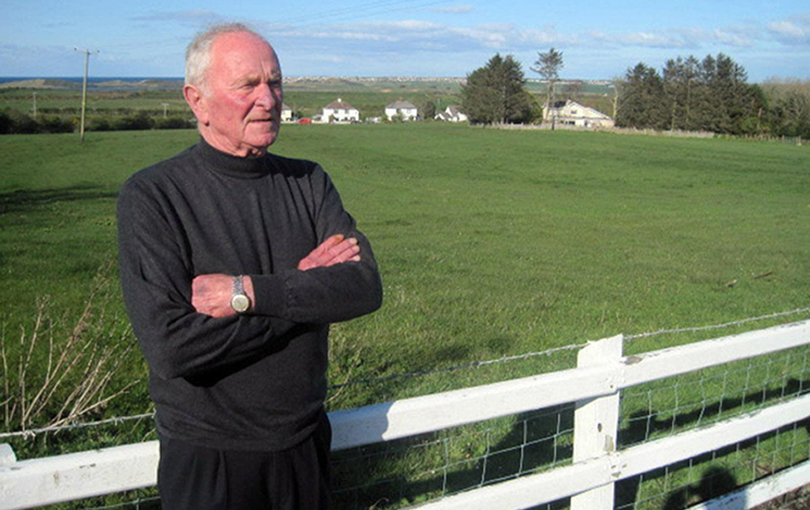

Gregg, who died on Sunday aged 87 in his native Northern Ireland, dreaded the calls on every anniversary of the disaster, he believed some people had a strange kind of morbid fascination with it. “If they want to be part of it, they can have the horror that goes with it.”

But Manchester United’s big keeper – signed only three months before the disaster - was the reluctant hero. Though only lightly injured, in the ripping, sparking, sliding black confusion of its immediate aftermath, he was convinced he had died and was now in the other place.

“Munich is not my life,” he said, “After the crash, I was dubbed the hero of Munich. That notoriety has come at a price. For Munich has succeeded in casting a shadow over my life that I’ve found difficult to dispel. I might have escaped the wreckage on that runway in Germany, but from that day until now there has been no escape.”

Gregg’s description of the actual crash when the chartered Elizabethan aircraft skidded off the end of the runway, smashed through the perimeter fencing, clipped a house and broke in half, its fractured pieces settling into marshy ground beyond the runway, was as visceral as it was vivid. “Bang!” he recalled of 3.04pm on Thursday 6th February 1958.

“There was a sudden crash and debris began bombarding me on all sides. One second it was light, the next dark. There were no screams, no human sounds, only the terrible tearing of metal. Sparks burst all around. I felt something go up my nose. Then something cracked my skull like a hard boiled egg. I was hit again at the front. The salty taste of blood was in my mouth and I was terrified to put my hands up to my head. I thought I’m dead, I’m in hell, hell fire, damnation and all that. I could feel the blood coming down my face.”

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Gregg was in the front half. Most of the 21 people who died instantly were in the back. Several of them had deliberately headed there because they thought it was safer.

Recovering his wits, Gregg crawled from the wreckage to be confronted by one of the crew who shouted at him that if he had any brain he would run before the whole plane exploded. Instead, he stood for a moment, considered the scene and then, shouting “There’s people alive in here”, went back into the buckled, broken fuselage.

“In the distance I could see people running away through the snow,” he recalled. “They shouted at me to run. Suddenly, from the cockpit came Captain James Thain. He has a little fire extinguisher in his hand and when he saw me he shouted: ‘Run, you stupid bastard it’s going to explode!’

Gregg heard a cry.

“I recalled a baby in the seat just across and I began shouting at the people running away to come back. I was angry and roared: ‘Come back, you bastards, there are people alive in here’. They kept going.”

“I climbed back into the aircraft. Scrabbling in the darkness, I came across a child’s coat. I thought of my daughter and was terrified of what I might find underneath it. There was nothing there.”

He heard another cry and went further into the wreckage and found a baby under a pile of debris.

“Unbelievably, the child only had one bad cut over one eye,” he recalled. “I crawled out with the child and headed to the direction of the people who’d been running.”

He handed the baby over and went back into the wreckage.

“As I dragged myself through, a woman exploded from underneath a pile of wreckage,” he recalled. “I forced the woman along with my legs. She was in a terrible state. There was a gaping wound to her eye, and I later discovered she has also a fractured skull and two broken legs. When she eventually regained consciousness this poor Yugoslav woman heard German voices and though the war was still on.”

Gregg couldn’t comprehend the scene around him. Much of the aircraft had been destroyed. He found Ray Wood, a fellow goalkeeper. He tried, but could not move him. He saw Albert Scanlon.

“His injuries were so severe I had to prevent myself from being sick. I left thinking Ray and Albert were dead.”

He desperately began to search for his childhood friend Jackie Blanchflower. Instead, he stumbled across Bobby Charlton and Denis Viollet.

“I thought Bobby and Dennis were dead,” he said. “Even so, I grabbed them by the waistbands of their trousers and trailed them through the snow for about 20 yards, away from the smouldering front of the plane. There were explosions everywhere, sending huge plumes of flame into the sky. It was horrifying.”

Gregg found Matt Busby “lying between what remained of the aircraft and the burning building. He was conscious. He was rubbing his chest and moaning: ‘my legs, my legs.’ His foot was pointing the wrong way.”

Gregg propped him up and continued to look for Blanchflower. He found him 30 yards away, lying in a pool of water and crying out that he’s broken his back and was paralysed. Blanchflower couldn’t move because the captain Roger Byrne was draped across him. Byrne was dead.

“There wasn’t a blemish and his eyes were open,” said Gregg. “I have always regretted that I didn’t close his eyes.” Blanchflower had been watching the seconds tick by on Byrne’s watch.

Eventually, people started coming to help, ordinary people, not firemen or ambulance crews. A local turned up in a VW coal lorry. The dead and the living were loaded onto the truck which sped so fast to the hospital that Bill Foulkes punched the driver’s head and told him to slow down.

“Despite what I’d witnessed on the airfield it was only in that hospital that the enormity of the situation hit home,” he said. “I stood at the window, bewildered and staring as the cars in the street below gradually disappeared under a blanket of snow.”

“To me, Harry Gregg has always been Superman,” said Mrs Vera Lukic, the Yugoslav woman he rescued.

Just thirteen days later, Gregg played in United’s first game after the disaster.

Three months later, he was in the World Cup finals in Sweden (he travelled by rail and sea) where 478 out of 600 journalists voted him the best ’keeper in the world. Runner-up was the great Lev Yashin with 122 votes.

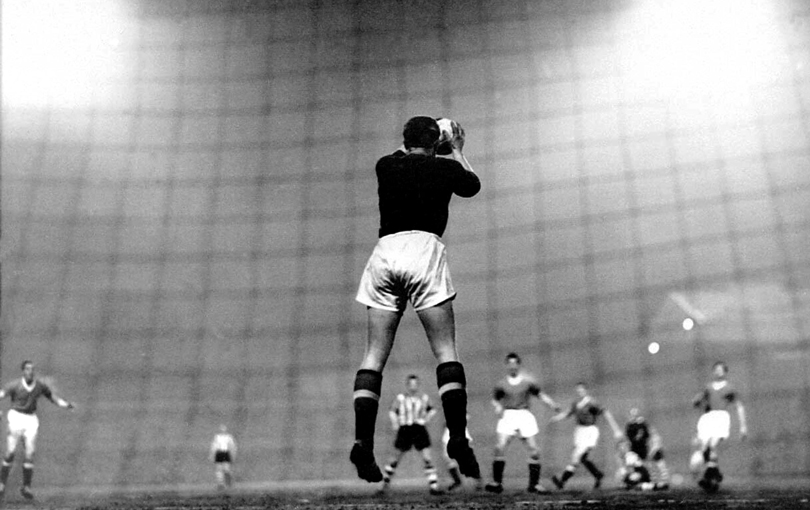

Gregg was bolshie, highly articulate, a fearless and sometimes highly unorthodox goalkeeper. He would stress the importance of what he called ‘moral courage’ – players not shirking responsibilities on the field – to new signings.

Gregg never won a trophy. Munich decimated the best team he played for, he was dropped for the 1963 FA Cup final and didn’t play in the 1964-65 title winning season. United bought Alex Stepney for a record fee for a goalkeeper in 1966, the year Gregg left - after years of a frayed relationship with Busby.

“It wasn’t just his fitness and amazing reflexes which made Harry a great keeper,” said his former teammates Paddy Crerand. “He read the game so well he could anticipate what most players were going to do with the ball, and when it came to tactics his views were always worth listening to. This made him unusual as the goalkeepers I had come across before had very little idea about the tactical side of the game.”

In his second 2002 autobiography, Gregg’s greatest wrath is reserved for those who sought to exploit and distort the Munich tragedy and its legacy. For survivors like Johnny Berry and Blanchflower, asked to vacate their clubhouses, it was ‘a constant battle against grief, guilt and eventually…bitterness’.

Gregg forgave the lack of support at the time, which he explained as possibly stemming from the chaos into which the club was plunged, but denounces what happened over the next four decades, where he feels the club exploited the disaster without helping the victims and their families.

After undistinguished spells as a manager with Shrewsbury Town, Swansea and Crewe, Gregg returned to Old Trafford as goalkeeping coach under Dave Sexton. He’d earlier played a part in the transfer of Jim Holton to Old Trafford and recommended that United to sign Bruce Grobbelaar well before the latter made his way to Anfield. He was particularly welcoming of new players.

“Harry was my good friend and told me that I had come to the club at the wrong time because things were changing there,” recalled Yugoslav international Nico Jovanovic, who was closer to Gregg than anyone else at the club. “There’s nothing a player can do about that.”

“Harry Gregg came in as a goalkeeping coach and we used to analyse videos together in the afternoon,” recalled Gary Bailey. “I liked that, but the other players thought that I was a bit of an idiot. Harry was good for me. My dad made me a goalkeeper and I was already good technically, but Harry worked me and got me stronger physically and mentally. He got me coming for high balls because he was an arrogant goalkeeper who had done that himself.”

His old teammates knew him best.

“Harry Gregg was a serious character, but I loved him devotedly,” said Paddy Crerand. “He was a tremendous goalkeeper, especially when you consider that he played for years with a damaged right shoulder. Time and time again he dislocated his shoulder until the surgeons decided the only way they could fix it properly would be to put steel pins through the bone. The operation was a success, but for years Harry was unable to raise his left arm much above his head. People saw him as indestructible, but he often played in tremendous pain.

“He lived around the corner from me and used to bring his family round. They were like the Von Trapps from the Sound of Music, forever playing various musical instruments. He wasn’t a big drinker, but he loved to sing. I’ve never heard anyone play the guitar and sing ‘Danny Boy’ like Harry Gregg. He was a Protestant, but his favourite goalkeeper was John Thompson at Celtic, who died after receiving a kick on the head after a collision with Rangers’ Sam English in 1931.”

Gregg could be very funny.

“The great (Manchester City goalkeeper) Frank Swift taught me a valuable lesson about how to win over even the most ardent away fans,” he said. “I put it into practice against Everton at Goodison Park. Instead of hurling a bit of abuse back as I would have normally done, I tried to appeal to that famed Scouse humour. One guy had been calling me all the names of the day. I decided to wind him up and asked him for a fag. His witty response was, “Fuck off you Irish bastard!” Eventually, though, he gave in and passed me a match and a cigarette…within minutes the Evertonians were chanting my name.”

A 2012 testimonial match at Windsor Park was well attended as United sent a strong team. He’d previously confronted his demons by going back to Munich and visiting the derelict airport.

“Because of what happened when we left this building,” said Gregg, pacing round the empty hall, an uneasy look on his face, “Manchester United changed from a football club into an institution.”

Rest in peace, Harry.

While you’re here, why not take advantage of our brilliant subscribers’ offer? Get the game’s greatest stories and best journalism direct to your door for only £12.25 every three months – less than £3.80 per issue! Save money with a Direct Debit today

NOW READ...

LONG READ Inside Lazio’s ultras: on the ground with Italy's most notorious fans

QUIZ Can you name the starting line-ups from the opening weekend of the 2019-20 Premier League season?

GUIDE Premier League live stream best VPN: how to watch every game from anywhere in the world

Andy Mitten is Editor at Large of FourFourTwo, interviewing the likes of Lionel Messi, Eric Cantona, Sir Alex Ferguson and Diego Maradona for the magazine. He also founded and is editor of United We Stand, the Manchester United fanzine, and contributes to a number of publications, including GQ, the BBC and The Athletic.