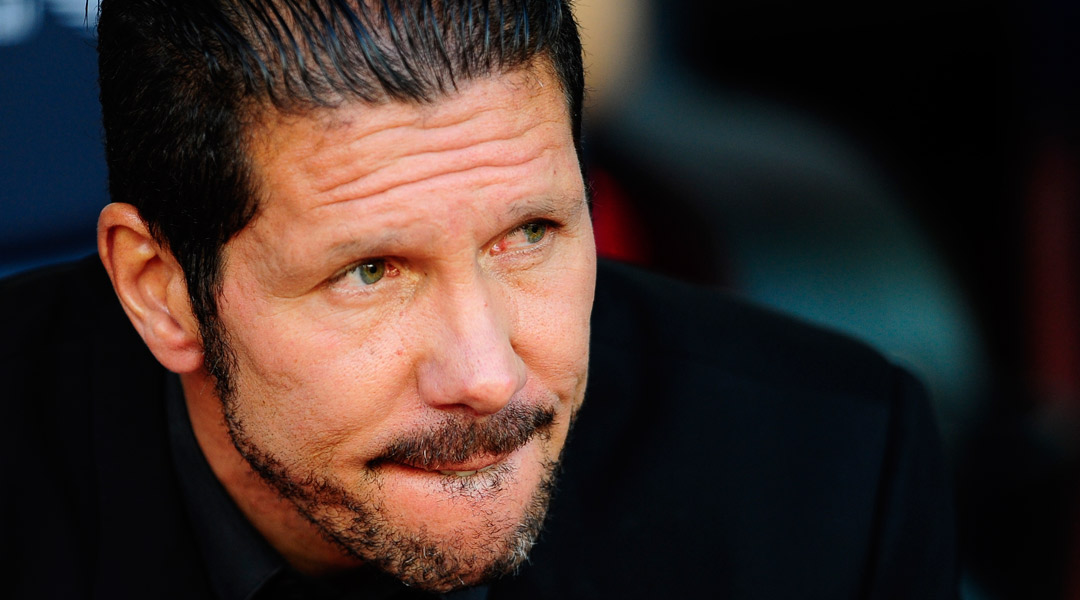

Revolutionary, family man, idol: inside the fascinating mind of Diego Simeone

Atletico Madrid's revered boss is no ordinary man, as Andy Mitten finds out from those who know him best...

Diego Simeone was a cult hero for his performances on the pitch when the Rojiblancos last won the league (and the cup) in 1996, bringing 250,000 out onto Madrid’s streets to celebrate. Simeone returned to Atleti as coach in December 2011 when they were 10th in the table, four points above the relegation zone and dumped out of the cup by lowly Albacete.

They’d just sacked Gregorio Manzano, who had been there only six months, the 49th managerial change under the club’s current ownership regime.

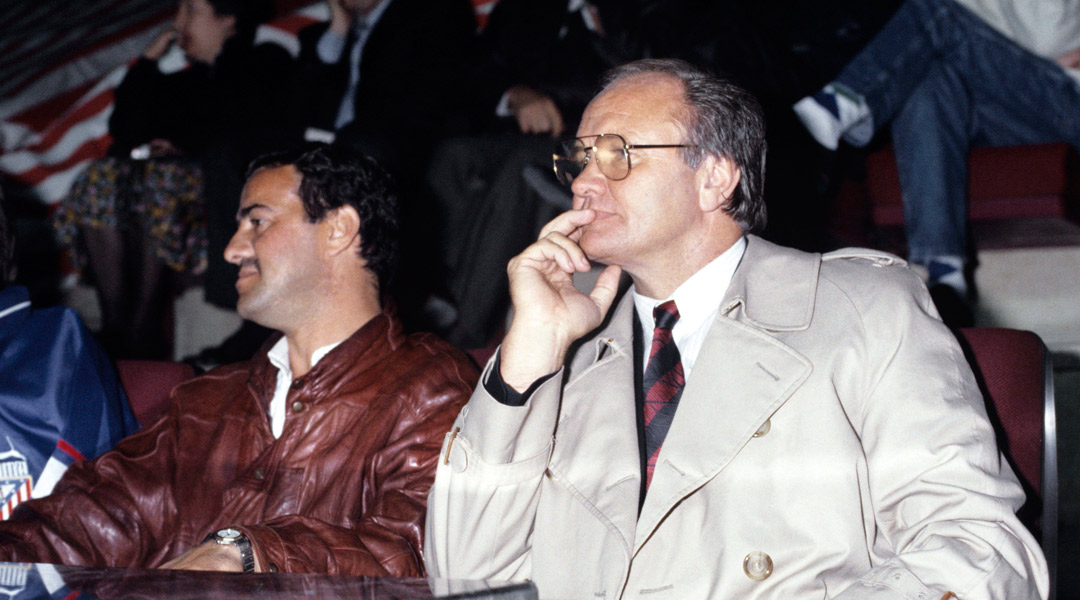

One of many was Ron Atkinson, appointed in late 1988. He propelled Atletico from near the bottom of the league to third, but was sacked after 96 days by a president he called ‘Mad Max’, aka Gil, who oversaw a vividly chaotic reign.

“Jesus was a big man, around 6ft 5in, built like a fighting bull with a larger-than-life personality – almost beyond the normal rules of sanity,” said Atkinson. “Controversy was his favourite, almost obsessive game and he did love hogging those headlines. He strutted around and left me with the impression of what Benito Mussolini must have been like in his early days of power.

“One morning the local edition of Marca dropped on my desk. There on the front page was my boss, dressed in a convict’s uniform, his huge jowly face peering through the bars of a prison cell.” That mocked-up tabloid stunt was prophetic: Gil would later be sentenced to jail for a litany of financial crimes, the chief being embezzlement from his own club.

Atkinson won 11 and drew two of his 15 games in charge but was dismissed, he suspected, because he refused to play the injured defender Andoni ‘the Beast of Bilbao’ Goicoechea. Atleti’s former doctor of 25 years had been sacked and taken legal action against the club. In one of his statements, he said that Goicoechea wouldn’t play again. Gil wanted to prove him wrong.

Although Atkinson had still not been told he was fired, Gil offered the job to assistant Colin Addison, who accepted. Atletico paid up Atkinson’s three-year contract in full. “Jesus Gil was an impressive character,” said Atkinson. “He was just too powerful for the stability of the club.”

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Atkinson next saw Gil three years later when he was commentating on an Atletico versus Manchester United match – which television viewers in Britain didn’t get to see, as Gil pulled the plug on the cameras 80 minutes before kick-off.

So Atkinson had no game to commentate on, but that didn’t stop Gil describing him as his favourite enemy, bursting into laughter and crushing him in a giant bear hug. “By that time Miguel Gil, the son of Jesus, took executive control of the club and the whole place seemed to reflect far more stability,” said Atkinson.

Gil Junior is still chief executive. Twenty-two years and 34 coaches after Atkinson, the hero of the first Spanish team to win the league and cup double took charge.

Warrior

“Milinko Pantic was the playmaker, but Simeone was the main man at the club – apart from Jesus Gil,” recalls Quinton Fortune, who played at the Vicente Calderon before joining Manchester United. “He did everything to win.”

Of his own style, Simeone said he played as if he was “holding a knife between his teeth”. He still does everything to win.

Simeone’s predecessor, Manzano, had lasted six months but his attempts to rebuild a side after the sales of Sergio Aguero, Diego Forlan and David de Gea in 2011 had faltered. That said, a bright spot had been the form of €40 million new signing Radamel Falcao, the Colombian striker from Porto.

Asked to compare Manzano with Simeone, the Brazilian Miranda, the best central defender in Spain this season, says: “There’s no comparison. It’s like I moved to a new team. Simeone is a great coach and is always trying to get the best out of every player. I’d say our side is 70 per cent better now. In all we’ve achieved these last two years, we owe a big part to him.”

Simeone doesn't do it all alone, though; assistant manager German ‘Mono (Monkey)’ Burgos is also credited with having significant influence inside the dressing room. The rock music-loving 44-year-old – and 35-time Argentina and former Atletico goalkeeper – is a formidable character.

When Jose Mourinho was complaining in a December 2012 Madrid derby, Burgos rose from the rival dugout, pointed and said “I’m not Tito [Vilanova] – I’ll tear your head off.” There was little chance that Mourinho would have tried pinching the giant monkey, though he did offer verbal retribution when asked about the incident. “Mono Burgos? Who is this?” he asked.

Burgos, a former bin man and AC/DC fan, once said: “I couldn’t play at Real Madrid because of how I look. They’d make me cut my hair. Atletico is synonymous with workers. Atletico fans are brickies and taxi drivers.”

“He [Burgos] compliments the Mister really well,” says midfielder Gabi. “They’re both very strong characters, but they share their knowledge and strategies. We trust him. It’s important to trust an assistant.”

Father and sons

Simeone has had to sacrifice a great deal to return to Atletico. In 2011, when the club came looking for him to take over, he phoned his nine-year-old son Giuliano at the family home in Buenos Aires. “Dude, I have to tell you that Atletico Madrid called me. They want me as coach.”

“Really? You’ll get to go against Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo?” replied Giuliano.

“Yes, sure, but I have to move to Spain.”

“But we’ll be able to see the matches?” A long silence follows. Simeone knows his family will have to stay in Buenos Aires. It’s too risky to keep moving them around the world with different jobs.

Besides, all three of his sons are footballers with River Plate – one of five clubs he coached before Atletico – with the eldest, 18-year-old Giovanni, having broken into the first team. He knows nothing will be more painful than losing day-to-day contact with his boys and his wife, a model. Giuliano realises he’s not moving to Spain. “But if you win, you’ll not come back,” he says.

“That killed me,” says Simeone, “I didn’t know what to say to him.”

Simeone had started in management in his home city of Buenos Aires at Racing, the club he supports and where he finished playing in 2006. He moved to Estudiantes (who he led to a first league title, the Apertura, in 23 years), River Plate (he won the 2008 Clausura) and San Lorenzo.

In January 2011, he joined Catania and fulfilled his brief of keeping the Sicilians in Serie A. He went back to Racing, his sixth job in four years, and led them to second in the league before Atleti came in for him. After family discussions, he was soon on the plane to Spain, charged “with positive energy”.

“I was called in an emergency, but the team was good. They just needed a little change,” he explains. “There were similarities between Atletico and Racing. Both have an unconditional following of fans and they want to win the title but historically lose out. Atletico fans feel that they should win like Barcelona. Fans, eh? They told me that I had to make the Champions League.”

Simeone met his players and got straight to the point. “He told us that he’d always pick the best team,” says Brazilian full-back Filipe Luis. “What I appreciate about him is that he doesn’t have any commitment to anyone, agent or director.

"He picks the team he wants to. If he thinks our most decisive player, Arda Turan, is not doing well, he’ll take Arda out. He feels free to change the team whenever he wants.” That’s not a given in Spain, where presidential influence can have a bearing on team selection.

But then Simeone has never been one for compromise, defining the terms for his team and players in relentless competition. “There is only one form of motivation, the lifeline of any team: internal competition. If there is no competition between players, the team dies. It’s the only situation which strengthens the coach.”

The Argentine is experienced enough to draw from his early work in management. “I don’t forget Estudiantes,” he says. “We managed to capture the football with which I most identified: practical, committed, simple, talented and from a collective effort.”

Respect

A club synonymous with talented individuals is now united with an unbreakable bond. “People would leak stories to the media which could be very damaging to the dressing room,” explains former player Diego Forlan. “I felt that the dressing room was tight, but I didn’t trust everyone close to it. We’d read negative stories – some true, some not – about us which undermined the team spirit. That was very frustrating as a player.”

Atleti’s shifting plates of power have long been their Achilles heel, yet even the seemingly eternal battles between Enrique Cerezo, the club president, and the chief executive, Miguel-Angel Gil, have calmed under Simeone.

Away from his family, Simeone works intensely on his project. “He does such an excellent job before the games,” explains Miranda, one of three Brazilian regulars in the team. “He is always asking the players to give 100 per cent on the pitch, he practically neutralises opponents’ strengths and he takes advantage of defensive weaknesses so we go onto the pitch knowing what to do. He’s one of the best coaches I’ve worked with.”

As many a coach has found to his cost, coming to a new club and installing a meritocratic selection system is fraught with potential problems. But then it helps if you’re a club legend.

“Manzano had a difficult situation from his first day as he had never been accepted by the fans,” says Filipe Luis. “He cared too much about not letting anyone be mad at him, rotating the team every single game. Simeone – no. He arrived when the team faced a relegation risk, but he had been an idol of the club as a player and that helped.”

An Atletico idol he certainly is; beat Real Madrid in Saturday's Champions League final and he'll become a god at the Vicente Calderon. Whatever the result, he's not far off that status already.

This feature is an extract from our December 2013 cover story, when we found out what makes Spain's new kings tick (that's official now and everything - don't say we didn't tell you so). Download the issue for iPad here.

Andy Mitten is Editor at Large of FourFourTwo, interviewing the likes of Lionel Messi, Eric Cantona, Sir Alex Ferguson and Diego Maradona for the magazine. He also founded and is editor of United We Stand, the Manchester United fanzine, and contributes to a number of publications, including GQ, the BBC and The Athletic.