A rich man's playground: what does the future hold for club ownership in the British game?

Jamie Ranger looks for answers as to what model best delivers a sustainable future for clubs, with so many irresponsible owners infecting the game...

The takeover, as any English football fan knows, prompts an uncertain future. For some fortunate clubs, it’s a golden ticket of admission to Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory, where Willy is portrayed by Sky Sports’ Jim White and the chocolate is some sort of ill-conceived metaphor for transfer activity.

For less fortunate clubs, a takeover is the equivalent of the witches’ curse from Macbeth, condemning once-proud institutions to self-implosion in an attempt to dethrone their rivals. Takeovers are perhaps the ultimate point of fierce contention for fans. On one side, there is the romantic, who sees football clubs as legitimate regional institutions that benefit their communities and ought to be treated with the care and caution one would reserve for an antique vase. On the other side, we have the pragmatist, who sees clubs as potentially lucrative machines for enthralling sponsors, advertising executives, and TV revenue.

Best of both worlds?

You can either have a club run for the community, or you can have a league that hosts the top players in the world game, but you can’t have both.

The debate is often framed between the preservation of identity versus the cultivation of an elite product: you can either have a club run for the community, or you can have a league that hosts the top players in the world game, but you can’t have both.

With more money in the English game than ever before, many more people are joining the football family, not for the sight of Sergio Aguero, Alexis Sanchez or Angel Di Maria in full flight, but rather as a viable opportunity to make some cold, hard cash.

However, since the recent top-flight success of clubs such as Swansea City, the prominence of fan-ownership models in the Bundesliga, and a spate of horrendously unsuccessful and unsustainable takeovers by real-life Bond villains, alternatives are being sought.

So how do the Premier League, Football League and the FA differentiate between the competent custodian who wants to build a sustainable model for a football club’s growth and the disinterested narcissist who is more interested in the quick buck? Well, essentially they don’t.

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Fit and Proper

The test is basically a ‘tick list’ to see whether an individual qualifies to be a director or an owner of a club, principally by checking previous conduct to see if they have any black marks against their name

While all three aforementioned bodies have separate tests, whether they be the FA’s Owners and Directors Test, or the (in)famous Fit and Proper Persons Test used by the Premier League, one thing remains abundantly clear: they don’t seem to be doing a very good job. As noted by prominent corporate lawyer Richard Barham of the excellent blog Law In Sport, they are all ‘objective’ tests; there is a form with a list of things you cannot have done, and if you can tick ‘yes’ next to all of them, then you pass. The problem with this approach is that it treats football club ownership as a position without any social responsibility, and ostensibly reduces competence down to a few hoops that pretty much anyone could jump through.

“The test is basically a ‘tick list’ to see whether an individual qualifies to be a director or an owner of a club, principally by checking previous conduct to see if they have any black marks against their name (e.g. criminal convictions, company insolvencies, significant involvement in another club etc).” In short, there are very few ways you can be disqualified using these tests; either you’ve already driven two clubs into administration, you’re trying to own multiple clubs at the same time, or you’re not as rich as you need to be.

Community conscious

The problem appears to be the absence of positive criteria around the stewardship of the club itself

The problem appears to be the absence of positive criteria around the stewardship of the club itself. Dr. Jonathan Michie, a professor at Kellogg College, Oxford, has written extensively on corporate governance within UK football clubs, and his assessment is unequivocal: if he could change one thing about the way clubs are run in the UK, he says he would “require them to be member-owned organisations run for the benefit of the community.”

Assuming such a model is unforeseeable in the near future, Michie argues that one question that must be asked of any prospective candidates for football ownership is: “what is their purpose in wishing to own the club, and what do they think they could and would deliver for the fans, the club and the local community.”

With television money soaring and sponsorship deals being brokered at record-breaking levels, many takeovers consist of consortiums of owners with no real interest in sport, but primarily concerned with maximising their slice of the club’s income before a quick sale to another investor.

The other prominent issue that Dr. Michie is concerned about is the diffidence of certain club owners, who often treat owning a football club as a “non-work and non-business part of their lives, along with social and other non-business activities, and therefore don’t take it as seriously as they should, and as they would if it were part of their professional work”. This serves to explain how so many billionaires with so many successful businesses can appear so useless when they are behind the reins of a football club: for them, it’s a little bit of weekend fun, or as Barham notes: “Some want to buy a club to make money. Some want to buy a club to have fun. Others do so for prestige.”

Let the fans be heard

While Barham does not favour the radical reorganisation of football clubs that Michie endorses, he appreciates that fan interaction is important, advocating an annual fan report explaining how the club is currently functioning, and would encourage football bodies to have a clear understanding of an owner’s motivations, and their exit strategy should the money or the enthusiasm for the club run out.

Some want to buy a club to make money. Some want to buy a club to have fun. Others do so for prestige.

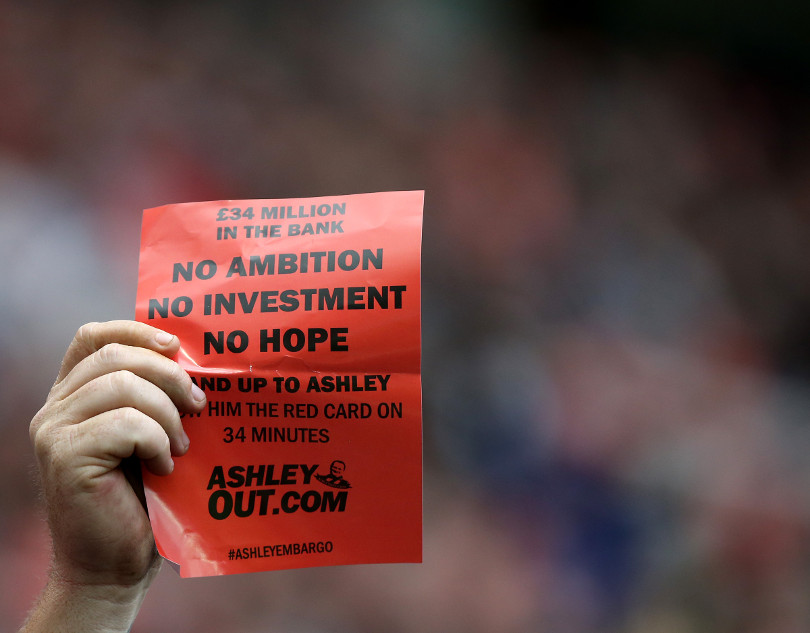

Another issue that many fans of a certain football club that definitely don’t play in orange may understand more than many is the notion of a takeover that goes wrong years later. You could start out with a perfectly competent owner, but if their business goes bust, or their decision-making gets more ethically dubious over time, there is no real way within the current rules for fans to wrestle back control, even at the point of insolvency, without having to quickly crowdsource millions of pounds.

However, the worry about changing the rules, or adding too many stipulations, would be that takeovers would take much longer to process than they do currently, and as many occur because the current ownership have run out of funds, financial instability, without league or state support, may increase.

If the only viable reform requires football associations to put more of their own time and resources on the table, it looks like the enigmatic owners, and their dugout yes-men, won’t be going away any time soon; keep the protest banners unfurled.