Robert Plant: Sing When You're Winning

"I was born in West Bromwich but they soon smuggled me out. It all started with Billy Wright’s wave..."

Normally, the word “seething” is spelt with just two es, but rock legend and Wolves fan Robert Plant enunciates it with such intensity that the best way to transcribe it is to throw a few more vowels in. “Seeeething – that’s how I’ve been these past few weeks.” Yet again, Wolves’ promotion campaign has gone down like a lead zeppelin. It was a season made all the worse for Plant and his side by ending so magically for local rivals Birmingham and West Brom.

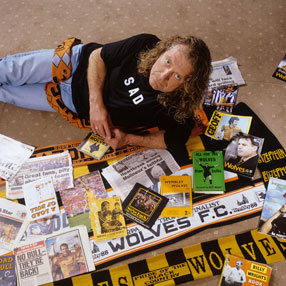

A sports bag stuffed with the souvenirs of almost half a century of supporting Wolves at his feet, Plant catalogues the many consequences of the season’s fatal finale with grim relish. “Some of my friends can only move under cover of darkness. When I play tennis, every time the ball comes over the net my opponents go ‘boing boing’ like the West Brom fans. The libido might be affected – getting it up might be a problem…”

While Wolves’ end–of-season ‘house of cards in a hurricane’ impression is now a traditional feature of the football calendar, so is their support among the Plant saplings beginning to wilt, as the patriarch is forced to admit. “My son Logan, who played for Inter Cardiff, came to me when he was about 22 and said, ‘Dad, I don’t want to do this anymore’.”

Logan opted for the academic life while Plant’s youngest son, after Wolves failed to do the necessary in the second leg of the playoffs, suggested that his weekends might be better spent sharpening his tennis. “He’s a good player,” sighs Plant senior. “But they can’t give up now. I’ve been going through this for 50 years and I can’t give up.”

He has, though, come damn close. In the decisive game at Molineux (which he attended after pulling out of a concert with the Gallagher brothers in front of 300,000 fans in Rome), he was so enraged by Norwich’s cavern-mouthed striker Iwan Roberts that “I started shouting, ‘Roberts, you prick!’ almost as if I was saying, ‘Come on – eject me!’ You can get banned for using language like that now. That might be my only way out.”

In a vain bid to make sense of it all, Plant jotted down a lengthy work of free verse drawing on the significant moments of his years as a Wolves fan on the back of the artwork for his new album, Dreamland. “Who gives a fuck about the artwork at a time like this?” he laughs, before reading out his poem, accompanied by emphatic hand gestures and a few shakes of the trademark tousled hair.

“At age five, Billy Wright waved to me ? my dad told me. First floodlit European matches in the UK versus Honved and Moscow Dynamo. 105 caps for England.

Like many of us, Robert Plant can’t really explain his choice of club. “I was born in West Bromwich but they soon smuggled me out of there. I think it all started with Billy Wright’s wave.” Wright was almost the David Beckham of his day: a player who symbolised England with a showbiz wife – Babs, of the Beverley Sisters. “I met him later,” says Plant. “Nice bloke, liked a G&T, told me his daughter was making a record. But I couldn’t get over the fact that here I was talking to Billy Wright.”

Plant was “too busy singing” to enjoy Wolves in the 1960s but his attachment to the club deepened throughout the 1970s. “We lost Peter Knowles to the Jehovah’s Witnesses but we had Kenny Hibbitt, an icon, who looked like a character out of Beowulf.”

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

In the close season of 1975, Plant and his then wife, Maureen, were badly injured in a car crash on Rhodes. Plant was not fully fit for two years, recording the vocals for his 1976 album, Presence, from his wheelchair.

“Physio Kevin Walters, Julie’s brother, and Wolves manager Sammy Chung helped me walk again,” he says. He walked, finally, into the Molineux directors’ box, which he found full of “furniture removers, insurance brokers and clueless fogies living in a scotch and soda, curled-up sandwiches world of self-congratulation.” He’s never returned to t�hose dizzy heights, preferring the simpler joys of a regular season ticket, the company of his friends and family and the freedom to give Iwan Roberts some verbal.

The board’s cluelessness became obvious as Wolves slumped to the Fourth Division. The lowlights are recorded in Plant’s poem – “Dougan’s consortiums, dodgy managers, official receivers, can’t afford to print programmes – we lose to Chorley, a team from the Pennines, who don’t even have a turnstile”. It took Steve Bull to turn things around.

“Bully jumped me once, against Bolton at the Reebok, and shouted ‘Here’s Planty, who’s this then?’” he recalls with pride. “He brought the place together with his charisma, with the way he’d leave two defenders behind him knocking heads with each other, and the way he would run back and dispossess an opponent while our midfield looked on in sleepy awe.”

Some of Bully’s observations on Wolves’ clubcall line have been immortalised at the end of the Plant B-side Oompah (Watery Bint) - Plant’s Pythonesque take on the lady in the lake. In 1988, ‘Planty’ wore his devotion to Wolves on the sleeve of his album Now And Zen, decorating the cover with a wolf motif. One of the most prized items in Plant’s record collection is a disc commemorating the club’s appearance in the semi-final of the Sherpa Van Trophy.

In football, as in music, Plant isn’t content to be a golden oldie. “OK, we won a couple of League Cup finals in the 1970s and it was great but it wasn’t amazing. That was so long ago; what matters is now.” That 1970s Wolves side did stop Leeds winning the double, although with typical perversity they then lost the 1972 Uefa Cup final to Spurs.

And what about Wolves’ traditional rivals from the Villa? A derisive snort: “Villa are…” he waves his arms as if to clutch the right adjective to describe Villa’s insignificance. “Villa are in another universe. They aren’t even a flicker in my subconscious.”

He reserves more animus for his club’s own villains, like Mark McGhee, who he once declined to have lunch with on the grounds that he’d have felt obliged to throw food at the dour Scot. But even that pales compared to the latest tragedy. “What happened?” he laments. “From 10 points clear, was it losing to Grimsby, piddling with Preston on Boxing Day? After an hour at Carrow Road, we were 1-0 up…”

But hadn’t he and other Wolves fans foreseen disaster? He smoothes out a photo from the Wolverhampton Express & Star, showing fans brandishing a banner which simply says, ‘You’ve let us down again’. “Maybe we expect it,” he says. “I burst into tears one Sunday morning in Sheffield when it first became apparent things were going to go wrong. When we were at the top we looked comfortable on paper, but it never looked comfortable if you went to the game.

“I’ve had a very bad few weeks,” Plant says with massive understatement. He had tempted the footballing gods by applying for his season ticket in advance, “thinking I’ll be seeing Premiership football next season for the same price I’m paying now”. There’s a rueful chuckle at his naivety, and with that he’s off to play tennis, steeling himself for the cries of “boing boing!” every time a return makes it over the net.

Nick Moore is a freelance journalist based on the Isle of Skye, Scotland. He wrote his first FourFourTwo feature in 2001 about Gerard Houllier's cup-treble-winning Liverpool side, and has continued to ink his witty words for the mag ever since. Nick has produced FFT's 'Ask A Silly Question' interview for 16 years, once getting Peter Crouch to confess that he dreams about being a dwarf.