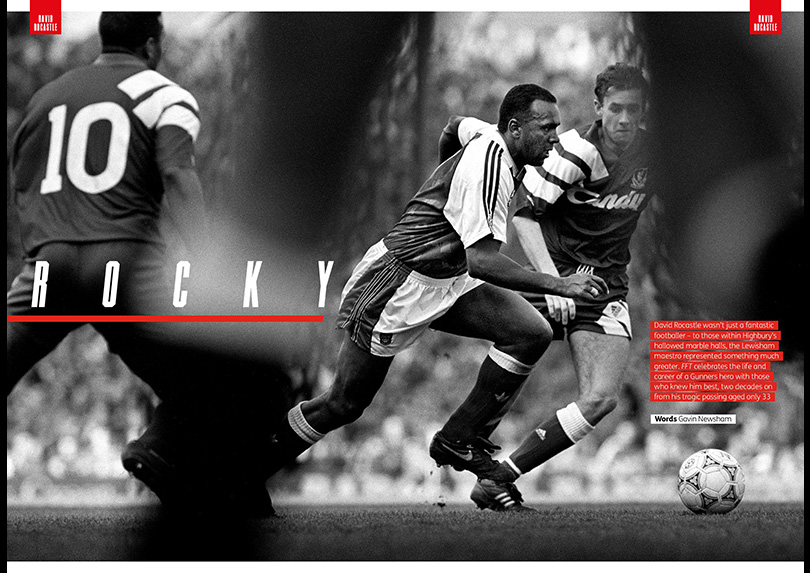

David Rocastle remembered: Celebrating the life and career of the Arsenal hero with those who knew him best

David Rocastle wasn't just a fantastic footballer – to those at Arsenal, the Lewisham maestro represented something much greater. On the anniversary of his tragic death aged just 33, FFT celebrates a genius

This feature on David Rocastle first appeared in the April 2021 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe now and get your first five magazines for £5

David Dein has a coffee table in his study. At first glance, it’s an unremarkable piece of furniture. Have a butcher’s underneath, however, and you will notice something unusual propping up the simple square of mahogany. There, dressed in Arsenal socks and shorts, are a pair of actual legs. These are no ordinary appendages, either – they are life-size replicas of David ‘Rocky’ Rocastle’s.

Dein’s table was a present from wife Barbara. Knowing how much her husband admired the Arsenal midfielder, she had also bought him a new wallet with a photograph of Rocastle inside, rather than one of, say, her or their children.

“As a member of the Arsenal board and in a position where you shouldn’t really have favourites, Rocky was unquestionably mine,” the former vice-chairman tells FourFourTwo.

But then again, David Rocastle always had that effect on people.

It is now over 20 years since Rocastle passed away after a battle with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, an aggressive variant of cancer which affects the immune system, aged just 33. Ask anyone who knew him and they all offer the same opinion without exception: not only was he an extraordinary player but, more than that, he was also an exceptional human being. Rocastle’s famous ethos was simple: “Remember who you are, what you are and who you represent.”

Born in the London Borough of Lewisham, Rocastle was brought up in Brockley on the same Honor Oak estate as friend and future team-mate, Ian Wright. When Rocastle was five, his father Leslie died from pneumonia aged just 29, leaving mother Linda to bring up her five children. David, as the oldest, was now the man of the household, and he had to grow up pretty quickly.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

“He was our role model and we all looked up to him,” his brother Steve explains to FFT. “He always had our back.”

At school, Rocastle was a model student. Although he thought about becoming a PE teacher one day, it was clear that his gift for football would take him in another direction. He soon found his weekends taken up by representing local club Vista, then Lewisham Way – a club set up specifically to give young black boys from the local housing estates an opportunity to play.

Nominally a central midfielder, Rocastle’s obvious talent meant he could play anywhere on the pitch. “It was hard to pin him down,” says Steve Rocastle. “If they were winning, Dave would be upfront, trying to score more. If it was tight he would drop back, making sure they didn’t concede. I know I’m biased, but he could do it all.”

Word started to spread about the boy from Brockley. He was offered a trial at Millwall, but the Lions declined to sign him. Instead, Arsenal scout Terry Murphy was impressed by Rocastle’s boundless energy and balletic grace on the ball, and eventually persuaded Gunners boss Terry Neill to offer him a place in the club’s academy.

Dein, meanwhile, first saw Rocastle play for the youth team a year later, in 1983.

“I remember coming home excitedly from the match and telling all my family, ‘I’ve just been watching the nearest thing to a Brazilian footballer you’re ever likely to see – and he comes from Lewisham!’” chuckles the former Gunners chief.

Arsenal striker Charlie Nicholas had also seen the teenager in action and subsequently frogmarched him over to his agent, Jerome Anderson, for a chat.

“In walked this kid with a big afro, maybe 15 years old, and Charlie said to me, ‘I want you to look after this young man as if he was your son – he’s a special player and a special person’,” Anderson recalls to FFT. “Knowing he had lost his dad at such a very young age, I took it upon myself to do whatever I could to help him.”

They became friends, and in time, Rocastle would even jokingly call Anderson ‘dad’ as he helped to negotiate his first professional contract with Arsenal. That day, in December 1984, Anderson had met Rocastle outside Arsenal tube station before heading across the road to Highbury.

“He was just like any little boy fulfilling his dream,” reminisces Anderson. “The contract was peanuts – I’d be surprised if it was £200 a week. But it wasn’t about the money, it was about the opportunity. ‘You do the business,’ I said, ‘and the money will look after itself’.”

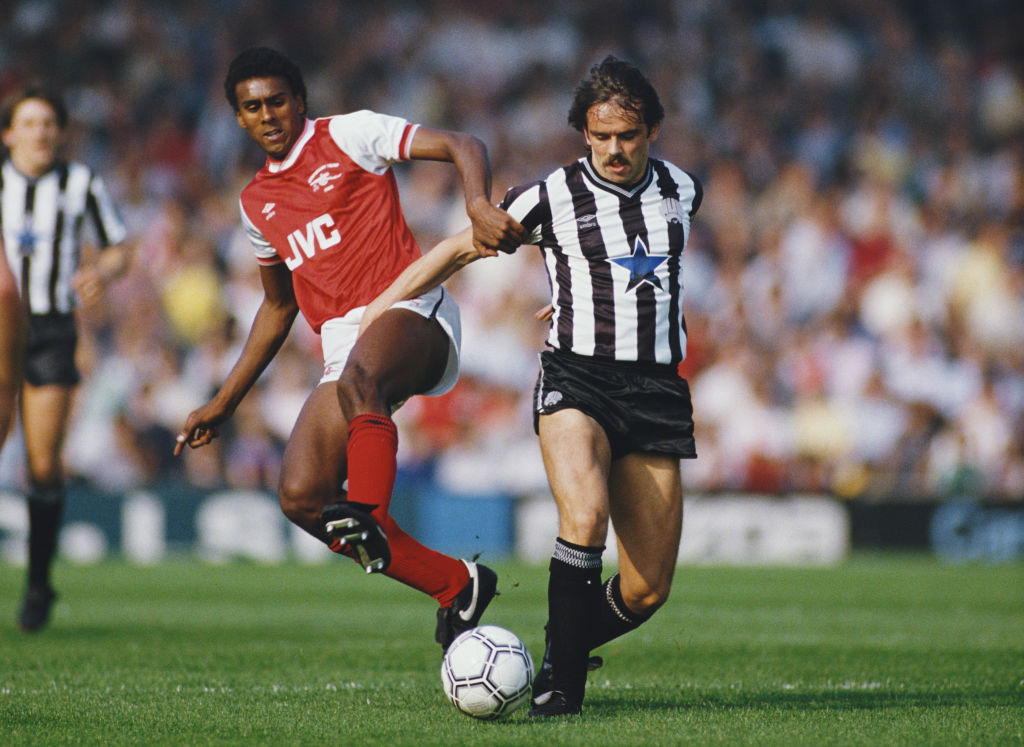

Rocastle didn’t have to wait very long for his first-team bow. Aged 18, he lined up against Newcastle at Highbury in September 1985, and although the game ended goalless, the teenager made enough of an impression to make 26 league appearances in his maiden season. He had everything. Yes, Rocastle was naturally strong and capable of bulldozing his way past opponents, but he was also blessed with a rare touch and an array of skills that infuriated some of his managers.

“You watch Cristiano Ronaldo’s stepovers, yet Rocky was doing 20 a game in his prime,” former team-mate Perry Groves tells FFT. “It drove George Graham mad.”

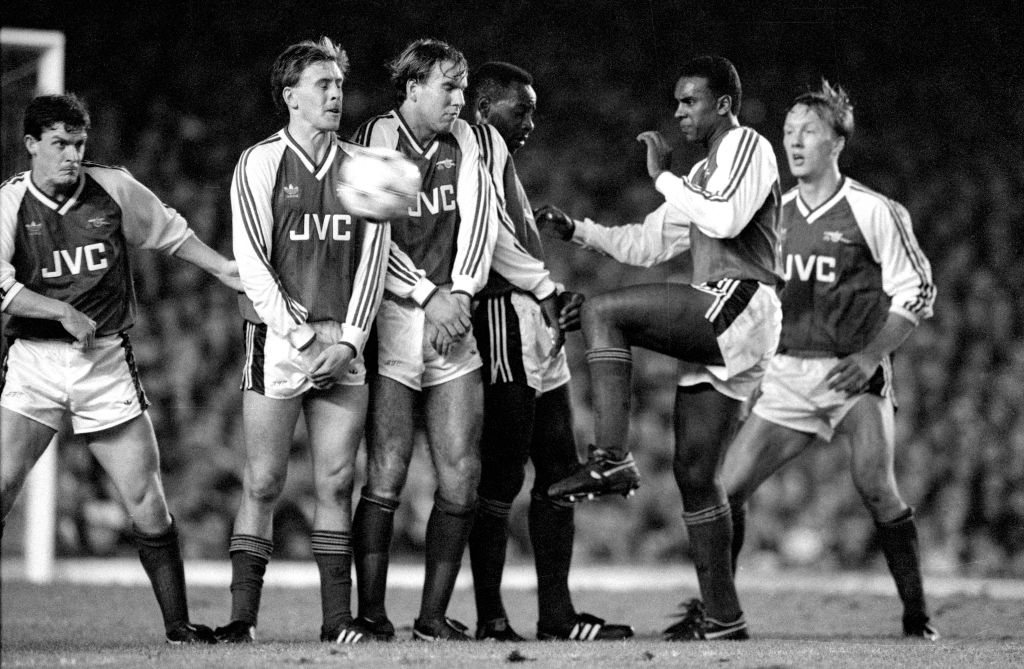

Rocastle could mix it as well. Tough in the tackle and possessed with what Tony Adams called “thighs like tree trunks”, he was in the midst of the infamous brawl at Manchester United in October 1990 for which both sides were docked points. “We went in there and stuck up for each other,” stated Rocastle. “At the Arsenal, we never, ever started any brawls – we just finished them.”

Rocastle landed his first winners’ medal in the 1987 League Cup Final, as Arsenal beat Liverpool 2-1 at Wembley. It was his display in the semi-final against arch enemy Spurs, however, that secured his place in Gunners folklore. Having lost the first leg at Highbury 1-0, Arsenal conceded in the return clash at White Hart Lane but rallied to win 2-1 and force a replay three days later. Again, Arsenal trailed to Clive Allen’s opener, but pulled level in the 82nd minute courtesy of Ian Allinson. Then it happened: with extra time looming, Rocastle slid home a memorable clincher to send the travelling mob wild.

By the 1988/89 season, Rocastle was in the form of his life – ever-present in the wondrous campaign which came down to one heady Friday night at Anfield.

That week, as the nation braced itself for a nail-biting title decider Arsenal had to win by two clear goals, Rocastle visited his agent. “He was completely unfazed,” says Anderson. “He looked me straight in the eye and said, ‘We’re going to win. It’ll be 0-0 at half-time, we’ll score early in the second half and we’ll win by two clear goals’. He was convinced.”

But everything was stacked in Liverpool’s favour. Kenny Dalglish’s side were unbeaten since New Year’s Day, hadn’t lost by two goals at Anfield in three years, had just lifted the FA Cup against Everton and had the public’s affection only six weeks after Hillsborough.

Rocastle felt the Gunners had their rivals’ number after a hat-trick of narrow League Cup third-round meetings earlier that season.

“Rocky was unplayable in the first game at Anfield and smacked one in the top corner – a proper worldie,” says Groves. “I remember him telling everyone after the game that we were the better team and had nothing to fear.”

He was right. Eight minutes into the second half of the title decider, Rocastle was fouled by Ronnie Whelan 40 yards out. His reaction to the high boot wasn’t anger or frustration, though – quite the opposite.

“You can just see the sheer determination in those steely eyes of his,” continues Groves. “He raises both fists – you can see how much he wants it.”

Sure enough, the Gunners scored from the free-kick as Alan Smith glanced home Nigel Winterburn’s centre. Up for grabs as Michael Thomas secured an improbable 2-0 victory in injury time, Rocastle’s prophecy had come to pass. The following morning, when most Arsenal players were nursing post-celebratory sore heads, Rocastle turned up at his mum’s house, bag in hand, like it was just another day. “We were all beside ourselves but it was like nothing had happened for him,” says his brother Steve. “He had his dinner and carried on as normal.”

However, just as it seemed everything was going Rocastle’s way, a knee injury late in the 1989/90 campaign halted his momentum – especially on the international front. Rocastle had earned his first senior call-up – after 14 appearances and two goals for the under-21s – alongside Des Walker and Paul Gascoigne in September 1988, when Bobby Robson picked the 21-year-old to play in a friendly against Denmark at Wembley. He quickly became a mainstay, playing in all but one of England’s six qualifiers for Italia 90.

The Three Lions advanced to the World Cup unbeaten, but Rocastle’s injury threatened his hopes of featuring in Robson’s final 22-man squad. He returned in late April, and scored a second-half winner off the bench against Southampton in his third game back. Sweeter still, Robson was watching on at Highbury. “I saw Bobby in the car park after the match, and he reassured me that as long as Rocky was fit, he’d be one of the first names on his list,” says Anderson.

The squad announcement now imminent, Rocastle headed to Singapore with Arsenal alongside two more England hopefuls: Alan Smith and Tony Adams.

“We hadn’t been there long when all three of us were summoned back to join a 26-man provisional squad, four of whom would later be culled,” Smith explains to FFT. “We’d had a few days’ training when Bobby stopped me and Tony on the way to breakfast and told Tony, face to face, he wasn’t going. But me and Rocky had to wait for the team flipchart meeting to discover our fate. Rocky was very unlucky not to go. We certainly had a good moan about it that summer.”

“It really annoyed him – and me,” laments Groves. “Rocky was in great form for club and country, so to miss out in the way he did just made no sense whatsoever. I remember him saying, ‘What’s happened?’”

Instead, Rocastle watched the tournament at Anderson’s house as England came within a whisker of reaching the final. It changed the lives of midfielders Gascoigne and David Platt – yet Gazza had only played twice during qualifying, and Platt not at all.

“To say Dave was disappointed about that is an understatement,” adds brother Steve. “He felt it wasn’t fair. I don’t know if it was an Arsenal thing, but for all three players to miss out a year after they’d won the title? It didn’t make any sense.”

Rocastle would never get to play at a major international tournament but did claim his 14 caps without experiencing defeat. His final England appearance came two weeks after his 25th birthday, when he took on Brazil at Wembley in a friendly best remembered for Gary Lineker scuffing a penalty and spurning the chance to tie Bobby Charlton’s record as the Three Lions’ joint-top goalscorer.

The knee injury that had all but cost Rocky his place in England’s World Cup squad soon proved an issue at Arsenal, too. An operation to resolve it hadn’t really worked, and while Rocastle’s trademark touch and technique remained, he wasn’t as mobile. It limited him to a paltry 18 league outings in the 1990/91 season as Arsenal won the First Division title again, losing just once. Arsenal boss Graham, however, was hell-bent on evolution. Twelve months after that second title in three years, Rocastle was now surplus to requirements. The Scot ushered his midfielder into his white BMW at London Colney.

“I’d parked out of the way because I was late and didn’t want to catch the manager’s eye, but as I walked over I noticed Rocky sat in the gaffer’s car,” recalls Groves.

“I thought he must be getting a bollocking, but as I got closer I could see that Rocky was in tears. At the time, I thought it might have been a personal reason. It didn’t occur to me that he was leaving.”

Eventually, Rocastle joined his team-mates where, voice wobbling, he told them that he was being sold, after 10 years and 277 games for the Gunners. “He was heartbroken,” says close friend Smith, “but Rocky took it on the chin like he always did.”

Boyhood pal Ian Wright was less impassive. “Wrighty was fuming,” smiles Smith. “He’d not long arrived at the club and yelled, ‘The only bloody reason I signed for Arsenal was to join up with you, Rocky!’”

Freshly crowned champions Leeds made their move, sealing Rocastle’s services in July 1992 for a club-record £2.5 million. Having driven the hardest of bargains with his Leeds counterpart Bill Fotherby, Arsenal vice-chairman Dein arranged for Rocastle to be transported to his new club for a medical – but not before he’d had a bit of fun. When the Gunners first opened their megastore in 1990, Dein commissioned Madame Tussauds to make life-size waxworks of Rocastle and captain Adams to promote the club’s latest kits. Now, though, Arsenal had no need for Rocastle’s doppelganger.

“I sent the waxwork up to Leeds with Rocky in the car and said to the driver, ‘When you get to Leeds, make sure David remains in the car, take the waxwork up to Bill Fotherby and tell him Mr Dein has sent David Rocastle for you’,” chuckles Dein. Fotherby was straight on the phone: “Deino! What’s this f**king waxwork?!” “Well, Bill,” said Dein, “what do you expect for £2.5 million?”

Overseen by gaffer Howard Wilkinson, the Whites’ success was built around formidable midfield quartet Gary McAllister, Gary Speed, David Batty and Gordon Strachan, the man who Rocastle had been recruited to replace. “David accepted that he would be trying to break into the best midfield in the country,” Wilkinson tells FFT. “But his track record was there for all to see.”

The trouble for Rocastle was that Strachan wasn’t quite so close to the end as expected. The 35-year-old carried on playing regularly for another two seasons and even collected Leeds’ player of the year award in 1993. With regular opportunities limited, Rocastle and Leeds chose to part company just 18 months after his move north.

“We didn’t really see the best of David at Leeds,” admits Wilkinson. “We never saw him consistently reproduce what he’d shown at Arsenal, where he was world-class.”

Leaving Elland Road for Manchester City in December ’93 signalled the beginning of the end for Rocastle’s playing days. The switch to Maine Road also failed to reignite his career, and he headed back to London the following August with Chelsea. There were also trials at Southampton and Aberdeen, plus loan spells with Norwich and Hull, where he scored on his debut against Scarborough.

Rocastle was still only 30 but nowhere, it seemed, could ever match what he had with Arsenal. “I don’t think he was the same again once he’d left Highbury,” says Groves. “It may sound over-sentimental, but I think leaving broke his heart.”

English football was apparently done with Rocky, but a fresh opportunity beckoned in the summer of 1998 as he joined Malaysian side Sabah after his Stamford Bridge release. Life, for a short time at least, was sweet. The Rocastles enjoyed the warmer weather and new experiences that Malaysia offered, and the locals took him to their hearts as Sabah reached the Malaysian FA Cup final.

In September 2000, though, Rocastle rang Anderson and mentioned in passing that he had a problem. “He said, ‘Dad, I’ve got a little lump on my neck’ – when he said that, I just went cold,” says Anderson.

Rocastle returned to the UK, and when the test results finally came back, his worst fears were confirmed. He had been diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

“The next few months were terrible,” says Anderson. “But he never moaned once, not even when he was having chemo and lost all his hair. He still had that big smile on his face. But he was very protective, too – I don’t think he wanted the people closest to him to know how ill he was.”

Brother Steve concurs. “I think we assumed that, as he was always very positive, he was receiving the right treatment and would be fine,” he says. “Looking back, I don’t think he really wanted to accept that it was terminal. He believed he would beat it.”

In early March 2001, Anderson contacted Dein about Rocastle’s illness, suggesting the pair visit him at his Ascot home. When they arrived, Dein was stunned into silence.

“To see what that disease had done to him was frightening,” he recalls. “You think, ‘Of all the people in the world...’ and wonder, ‘Why Rocky?’”

While there, Dein presented Rocastle with a new Arsenal shirt, signed by the squad with his name on the back. “Rocky never played for us in the Premier League and never wore the red shirt complete with his name on,” continues Dein. “He was thrilled with it.”

As Rocastle’s health deteriorated, he was moved to Wexham Park Hospital in Slough. Anderson visited him again, meeting up with Rocastle’s wife Jan. They sat together in silence, holding Rocastle’s hands as he lay motionless on the bed.

“We knew that he didn’t have a lot of time left,” explains Anderson. “Suddenly his eyes opened, his face lit up and that smile of his broke across his face. I don’t know if he had seen the bright light they always talk about, but it was an almost spiritual moment – I’ll never forget that.”

David Rocastle died on March 31, 2001. The same day, Arsenal beat rivals Tottenham 2-0 at Highbury. Robert Pires – wearing Rocastle’s No.7 shirt – opened the scoring.

Five days later, Rocastle’s funeral was held at Windsor Parish Church. There was neither a spare seat, nor dry eye in the house as both the football community and Rocastle’s family gathered to pay their respects. “It was tough seeing these big, strong guys that David used to go into battle with every week, standing there crying,” says Steve Rocastle.

“South London must have been empty that day,” says team-mate Smith, who was one of the pallbearers alongside Adams, Wright, Thomas and Paul Davis.

Anderson, meanwhile, provided the eulogy. “I’ve no idea how I even managed to speak,” he remembers.

Rocastle’s son Ryan – Arsenal’s mascot for the 2001 FA Cup Final against Liverpool – was only nine when his father passed away. Two decades on, recollections of his dad remain sketchy – especially his playing days. Clips on social media and YouTube have been helpful, as have the endless memories shared by his family and dad’s old team-mates, including his godfather Smith.

“I was so young when he died that I didn’t really realise how popular he was – not just at Arsenal but at the other teams he played for,” he tells FFT. “It only dawned on me in Arsenal’s last season at Highbury when they had a day in aid of the David Rocastle Trust, the charity set up in my dad’s name.

“I started seeing all these people with No.7 shirts and ‘ROCASTLE’ on the back. I guess he will always live on.”

Of that Ryan can be sure. It’s 20 years since his dad fought his last battle, but Arsenal fans will forever know what Rocky represented.