The incredible adventures of Romario and Stoichkov in Barcelona

They were the greatest strike partnership ever seen, but their mercurial relationship tore them and Barça apart after just one year

Please note: this feature originally appeared in the February 2010 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe today! 5 issues for just £5

For once there were no excuses, even though there was an excuse. There was no ranting about the ref, no bemoaning bad luck, no recriminations over the foreigner rule that forcibly left Peter Schmeichel on the bench. November 2, 1994, and Manchester United had been sliced apart by Barcelona in a performance of such brutal beauty, such wonder, that there was no point complaining. There was just acceptance. The best team had won, and won brilliantly. “We have been well and truly slaughtered,” admitted Alex Ferguson. “In the end, it was a humbling experience for us.”

So humbling, in fact, that Paul Parker still refuses to set foot inside the Camp Nou. He continues to have nightmares about the 4-0 hammering his side suffered. Parker’s United team-mate Gary Pallister remembers it as “the one time in my career when I came off the pitch and just had to accept that I hadn’t been able to get anywhere near my opponent. I was completely shell-shocked afterwards.”

Barcelona’s performance had been awe-inspiring, La Vanguardia describing it as a “recital.” “Barcelona humiliate United,” added The Times.

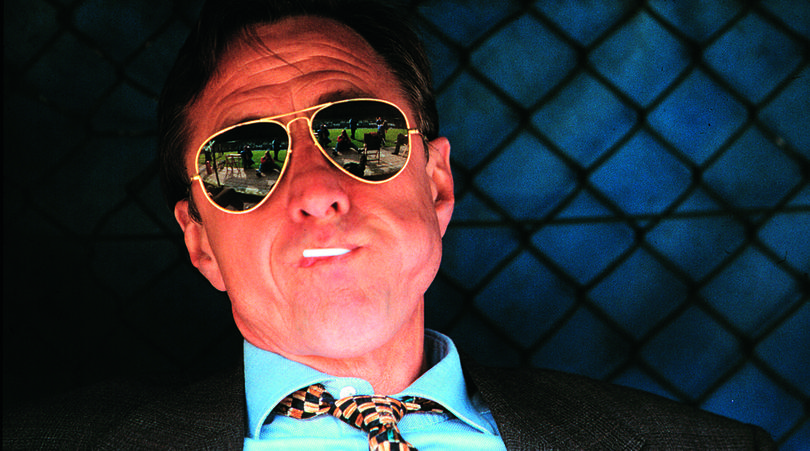

At the heart of that world were the most dashingly impressive strikers on the planet, the outstanding performers from that summer’s World Cup – Romario and Hristo Stoichkov. Romario was Brazil’s best player, Stoichkov USA 94’s top scorer as Bulgaria incredibly reached the semi-final.

A month after the United game, Stoichkov was named European Footballer of the Year. Together, they were arguably the best partnership the Camp Nou had ever seen. They were certainly the most excitable, as swift with their tongues - and sometimes even their fists - as they were with their feet.

That night, the Brazilian scored one and the Bulgarian two – the second, his 100th for the club. “We just couldn’t handle the speed of Stoichkov and Romario,” Ferguson recognised. “The suddenness with which they attacked was a new experience.”

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

“United had no answer to the skill, speed and imagination of Stoichkov and Romario, at times moving through their defence with an ease as impudent as it was embarrassing,” wrote David Lacey. “Pallister and Bruce were both auditioning for the role of Juliet: Romario, Romario, wherefore art thou Romario? And nobody had a clue about Stoichkov’s whereabouts.”

“When Barcelona are on their game, their superiority is insulting; they leave the opposition looking utterly ridiculous,” said the former Barcelona player Lobo Carrasco. “Tonight, Barcelona took revenge for what happened to them in Athens.”

What had happened in Athens six months earlier was that Barcelona had unexpectedly lost the European Cup final to Milan. Not just lost it, been defeated 4-0. Now, they had learned. Now, the four-time Spanish league champions and European Cup runners-up, the greatest side in the club’s history, were ready to go one better, led by this incomparably brilliant pairing. Humbling United was a warning; a glimpse of a future in which Stoichkov and Romario, Romario and Stoichkov, would rule the world.

Last dance

Only, it wasn’t. Instead, it was the last waltz; a brilliant final performance from a once great side. Two months later, Romario had gone. Six months after that, so had Stoichkov. And Andoni Zubizarreta. And Michael Laudrup. Soon, coach Johan Cruyff would go. The trophies went too – it was three years before Barcelona won anything again. Athens would prove a watershed, not a lesson. The dream partnership had presided over the death of the Dream Team.

It had all been so desperately short lived. Romario partnered Stoichkov for the 1993/94 season, plus the opening months of 1994/95, demolition of United included, and that was it. They had barely been together for a year.

But what a year. A kidnapping. Punch-ups. Fallings-out. Tears and tantrums. A proud father. An even prouder Godfather. A Scandal. A mistress. Or five. Paparazzi. Betrayal. Red cards. A league title, won in the final minute of the final day. A historic thrashing of the eternal enemy. A European Cup final. And goals. Loads; more than 50 between them, Romario finishing the 93/94 league season with 30 in 33 games, having scored a stunning five hat-tricks (one on the opening day, another, against Atletico Madrid, despite having two goals disallowed), and finishing his Barcelona career with 53 in 82 games.

Ask fans to name the best 10 Blaugranas in history, and virtually all of them will include Stoichkov and Romario. So important was their impact, so intense the reverence with which they are remembered, that the inescapable fact they only played together for a year seems somehow perverse. Surely, it must have been longer. And yet it wasn’t. They’d packed a hell of a lot in a year and then fallen out, each going their own way, never to speak again. Together, Romario and Stoichkov did it all. They became legends.

Bad milk

In March 1995, Stoichkov went on Spanish radio and declared: “It’s Cruyff or me.” The tensions that simmered below the surface were laid bare; in a phrase, Stoichkov had revealed that he was preparing to leave.

The Real Madrid goalkeeper Paco Buyo was quick to try to capitalise. “If it’s true that Cruyff doesn’t want him, and I can’t for the life of me believe it can be, then I will talk to whoever I have to make him join us. I’ll do whatever it takes.” “Stoichkov,” insisted Jorge Valdano, now general director at Real Madrid, “is a predator – a beast who is only satiated by the flesh of his victims.”

“He is the best forward in the world,” added Carrasco. “He can do everything. He has talent and class, he can run like Carl Lewis, play passes like Ronald Koeman, and finish every bit as well as, or better than, Gary Lineker – and on top of it all, he’s got mala leche.” Mala leche literally means bad milk; it is edge, a fearsome temper, aggression, competitiveness… and a touch of madness.

It is also exactly the point: Cruyff had focused on Stoichkov as much for his temperament as his talent. “I could talk about Stoichkov forever. He came to Barcelona because we needed him,” Cruyff recalled. “He had speed, finishing and character. We had too many nice guys, we needed someone with mala leche.”

Stoichkov had it in urn-loads. During his first ever game against Real Madrid, he was sent off for stamping on the ref, an act that earned him a six-month ban, later reduced to two. Another red card came for two yellow cards – just six minutes into a game. During a pre-season friendly, another ref approached the Barcelona bench to warn Cruyff: “Either calm that bull down or I’ll send him back to the corral.” Cruyff replied: “What am I supposed to do?”

He was, recalls the man who received the infamous stamp, “an angel off the pitch but the devil himself on it”. “If he’d been an actor, Stoichkov could have been Mel Gibson in Mad Max, Clint Eastwood in Unforgiven or Harrison Ford in Blade Runner,” noted one Catalan columnist – and the fans loved him for it.

It was his character that made him such a hit; the ability to embrace barcelonismo; the fact that he lived every match so intensely, that he boasted a hatred of Real Madrid so visceral, so public, that he kicked a seven-year-old boy out of training once when in charge of the Bulgarian national team because he turned up in a Madrid shirt. “Every game against Madrid was life and death for me,” he says, “the injustices of the past [against Barcelona] became mine, too.”

La Vanguardia hit the nail on the head when it declared: “We’re all Stoichkov; his story could be the story of the millions of Barcelona fans who are transformed when they come to the Camp Nou.”

Covered in Vaseline

Romario’s charms were different. With his wide hips, big, low-slung backside and powerful thighs, he was unique; electric, precise, utterly unpredictable. No one had ever seen a player like him. Technically impeccable, in small spaces he was unstoppable. He did things that appeared barely plausible and had never been seen before - from back-heels, to flicks, to incredibly delicate lobs known in Spain as vaselinas. Valdano famously described him as a “cartoon footballer”. “He is a juggler, a magician, a penalty area artist, a virtuoso,” cheered the Catalan daily Sport. “He does what others can’t – and does it with alarming ease.”

“I always regretted not wearing a hat so that I could take it off to him after he left the Osasuna goalkeeper covered in vaseline and solitude,” wrote the intellectual Manuel Vazquez Montalban. “He has feet as sensitive and soft as Dalí’s clocks. His finishing should provoke ridicule and hatred in goalkeepers but Romario inspires a kind of religious feeling instead. It would not surprise me if goalkeepers carried a notebook and pen around with them so that they could ask him for an autograph after every goal. He bends space and time. We have been lucky enough to see him out on the turf and unlucky enough not to have a poet like William Wordsworth around to describe him.”

Not that Stoichkov was overly impressed. When Barcelona signed Romario from PSV, the Bulgarian made his feelings perfectly clear in the media; league rules meant that only three foreigners could play at any one time and Barça already had Stoichkov, Koeman and Laudrup. “Signing a fourth foreigner is plain stupid,” Stoichkov snapped, “but if the board think it is absolutely necessary and they asked for my opinion I would tell them to sign [Bulgarian Lubo] Penev. How much does Romario cost? 600m Pesetas? I’d take 200m from my own pocket and sign Penev.”

It was classic Stoichkov; blustering, outspoken, emotional. It also threatened to cause problems - especially with Romario, a man who came with a reputation that he didn’t hide. “If saying things to people’s faces and saying what I think without holding my tongue, if having a strong character and not accepting impositions is controversial,” Romario told the Spanish media, “then yes I am controversial.”

It appeared set for a disaster. Romario and Stoichkov were contrasting personalities but, in Cruyff’s words, had the “same problem”: they both thought that the team was there to serve them, not the other way round. “They constantly battled to see who would get more goals,” remembers the former Barcelona director Josep María Minguella, who represented both players.

Neither could take being left out. “When Stoichkov was on the bench,” one team-mate recalls, “he could start a fight with his own shadow. And when Hristo’s angry, he’s dangerous.” “Hristo was peculiar,” says Minguella. Another team-mate describes him simply as “a bit dense”.

“I remember one time that Romario was left out and I couldn’t even talk to him, he was in such a funk,” remembers Stoichkov. The problem was that being left out was inevitable. With four foreigners in his squad – and four brilliant foreigners too – Cruyff adopted a rotation policy that satisfied no one, the front two least of all.

Unlikely friends

It appeared a recipe for disaster. And yet, oddly, Romario and Stoichkov became the best of friends. “Romario basically never spoke to anyone in the squad,” one team-mate recalls, “he did his own thing on his own terms all the time.” The one person he did speak to was Stoichkov. “It seems bizarre and I ask myself even now how it was possible,” Stoichkov says. “He was introverted and I was the reverse. He likes to sleep, I like to live. We were night and day. But we became good friends right from the start. We were inseparable.”

Their kids attended the same school, their wives, Monica and Mariana, became best friends. They protected each other; when Romario got a red card for punching Diego Simeone, Stoichkov admiringly remarked: “It was worthy of Mike Tyson.”

And Stoichkov knew a thing or two about punching people. He even did so in defence of Romario’s honour. The Brazilian was in Rio on international duty when his wife gave birth to a baby boy imaginatively named Romarinho. He was determined not catch a first glimpse of his son through the media and appealed for journalists not to get too near. Stoichkov played Romarinho’s bouncer to make sure of it - and one photographer at the hospital got a Bulgarian right hook for his trouble.

When Romario arrived – “two flights late, which was typical Romi”, as Stoichkov recalls – it was the Bulgarian who collected him from the airport and took him to the hospital. When Romario found out his father had been kidnapped, it was Stoichkov he was with and who offered support. When he found out that his father had been liberated it was Stoichkov he smothered in relieved kisses. And when it came to chose a Godfather for his son, it was Stoichkov who was the obvious choice.

Together, they were a devastating partnership on the pitch too: “Hristo enjoyed that year with Romario more than any other,” says Minguella. The goals are a testament to that. So too the league title and some of the most glorious nights in Barcelona’s history, none more so than a 5-0 win over Real Madrid in which Romario scored a hat-trick and produced a play that, Stoichkov insisted afterwards, “would go down in history”.

He was right. Turning almost a full circle, Romario dragged the ball with him, his foot never losing contact with the leather, pulling it across the floor, gliding like a bowling ball on a varnished lane, before finishing. No one had ever seen it before; it became known as the cola de vaca – the cow’s tail, forever associated with the Brazilian.

“I have never known a player able to do the things in the area that he did,” Stoichkov recalls. From that day on, Barcelona were unstoppable. They collected 28 of their final 30 points to win the league after Miroslav Djukic missed a last-minute penalty for challengers Deportivo de La Coruna on the final day. Barcelona’s cracks had done it again. “We silenced those who said the Dream Team was dead,” Stoichkov declared.

Not so fast

In fact, the critics were right. Other cracks were appearing – both for the club and their dynamic duo. Defeat in Athens was humiliating and unexpected but it was not an accident.

Cruyff’s rotation policy had angered men as mild-mannered as Michael Laudrup and Ronald Koeman, even if the results were often spectacular. Stoichkov missed four Champions League games and was subbed in 15 of his 30 league games. The fact that it is Stoichkov himself who points that out says it all. Laudrup missed the European Cup final.

Worse were Cruyff’s public attacks on them. “When we win it’s down to Cruyff, when we lose it’s the players’ fault,” Stoichkov snapped. Goalkeeper Zubizarreta was told he wouldn’t continue; Laudrup decided he couldn’t continue.

Meanwhile, Stoichkov was growing increasingly concerned by Romario’s lifestyle and the company he kept. “People came between us and I tried to warn him,” Stoichkov says. Romario resented the intrusion. He had ignored Stoichkov’s advice and decided to stay in a suite on the 17th floor of the Hotel Reina Sofia rather than move into a house next door. Later, he moved to a hotel in Sitges but kept his room at the Princesa Sofia (for, said the gossips, his mistresses). The wives remained close friends but the footballers drifted apart; Stoichkov sided with Mrs Romario more than Mr.

“Romario’s lifestyle, his constant coming and going caused problems with his wife,” Stoichkov recalls, rather euphemistically. The Brazilian was teetotal but had other vices. A team-mate puts it bluntly: “Romario was only interested in two things: football and fucking.” A few years later, Romario insisted: “If I don’t go out at night, I don’t score goals.”

Increasingly, he appeared not to be that interested in the football. One former Barcelona player recalls training sessions when the Brazilian “could hardly move” and was “practically falling asleep” after the previous night’s exertions. Cruyff sent him home from one session and had another confrontation with the Brazilian after he overslept and arrived an hour late to a team meeting. Cruyff had warned that Romario’s attitude in Holland used to be one of “If I don’t want to train, I won’t train”.

Used to be? Still was. “He lacked discipline,” a resigned Cruyff later admitted. Romario didn’t care. “It’s not the first time I’ve had an argument with Cruyff and it won’t be the last: I say what I think and no one will ever change me,” he said.

One night Romario was caught with a girl. A week later she was on the front cover of the magazine Interviu. A charitable soul pushed a copy under his hotel room door. The first person to see it was Romario’s wife. “Romario’s skill on the pitch was in lying with his body,” Valdano says, “in the end it was his undoing off it too: he lied to his president to go off with two blondes.” For Stoichkov the magazine under the door summed it up: “Someone had,” the Bulgarian insists, “taken advantage of their ‘friendship’ with Romi and sold him out.”

So long

The last straw came after the World Cup, dominated by the Barcelona forwards. Romario failed to return to the Catalan capital. In the Camp Nou dressing room, the rest of the squad took it out on Stoichkov, sniping: “Some friend you’ve got!”

By then, though, the friendship had almost died; saddened, desperate, the Bulgarian had tried ringing the Brazilian to plead with him to return to Catalonia. But the calls went unanswered, the messages ignored. This time it was Romario who felt aggrieved. Stoichkov and his family were supposed to be travelling to Brazil after the tournament for Romarinho’s baptism, before heading off on holiday together. Hotels and flights were booked. But the Bulgaria squad was called to a reception with the president Jelei Jelev and Stoichkov didn’t make it to Brazil.

When eventually, two weeks late, Romario appeared in Barcelona, everything had changed. “He trained alone and we hardly spoke,” says Stoichkov. “Then we had another argument because I didn’t like his friends at all. I tried to split him from them but I failed. It was never the same again.”

The United match apart, the Bulgarian was right: that following season Romario scored just four before departing. Stoichkov got only nine. Barcelona finished fourth. “Romario never came back after the World Cup. His body was there but his mind was still in Rio,” Stoichkov says. “Some joked that the man in Barcelona was a lookalike, his performances were so bad.”

It had been good – very, very good – while it lasted, but it was all over. There was just time for one last dance for old times’ sake; a moment’s glory that, beneath the perfect veneer, was a sad lament for what could have been. A virtuoso display, just like the good old days. A display so good that even Alex Ferguson couldn’t complain.

This feature originally appeared in the February 2010 issue of FourFourTwo.

While you're here, why not take advantage of our brilliant new subscribers' offer? Get 5 copies of the world's greatest football magazine for just £5 – the game's greatest stories and finest journalism direct to your door for less than the cost of a London pint. Cheers!