The secret lives – and hilarious stories – of football's player liaison officers

The popular perception of professional footballers as pampered prima donnas is over-simplistic and wrong... except when it isn’t. Meet the player liaisons who must cater to their every whim

The judgement that rained down upon them was Old Testament Biblical in its fury. England had been eliminated from Euro 2016 by Iceland, and the nation’s pundits – expert or otherwise – sharpened their tongues against all of the players involved.

Radio rager Danny Baker went bananas about “useless, over-indulged, mollycoddled sh*ts”. Rent-a-gob Julia Hartley-Brewer, who should perhaps invest in a dictionary, fumed about them being “overpaid nonces”. (She later confirmed she meant ‘ponces’.)

Of the ex-pros, Chris Waddle bizarrely said the players were “all just headphones”, while Ryan Giggs called them “robots” and Paul Scholes claimed they were “treated like world champions before being successful”. Jamie Carragher then dubbed today’s players “the academy generation”, adding that they are “soft physically and soft mentally”. The former Liverpool defender explained: “With personal assistants, Player Liaison Officers, nannies and agents organising every detail, players don’t even know how to book a holiday or a dentist’s appointment.” Our brave Lions, it seemed, were hapless, helpless man-babies.

Several notorious stories have been told over the years to reinforce such sentiments. Patrice Evra – who, it should be noted, made it to the final of Euro 2016 despite being what some might dub mollycoddled – once praised Manchester United fixer Barry Moorhouse by saying: “Whether you have a problem with your car, jacuzzi or the light, he is there.”

And, suggesting it isn’t a new phenomenon, Bolton’s Player Liaison Officer (PLO) was once tasked with helping new recruit Les Ferdinand find somewhere to plonk his helicopter so that the striker could commute from London.

PLOs themselves have produced some fine yarns of player idiocy, too. Manchester City’s Layachi Bouskouchi recalls being phoned by one who had been stopped by the police for driving at 130mph, asking whether he should give a false name, and another instructing him to walk his Golden Retriever, adding that the dog “only spoke French”. Perhaps, most famously, Alain Goma once called Fulham PLO Mark Maunders because his goldfish was “swimming round the wrong way”.

But is it fair to blame a new generation of helpful employees for footballers being able to score a worldie but not plug in the telly, or are they performing a vital function? Are we getting ourselves close to the diva-hell realm of a cocaine-era Elton John, who once ordered his manager to stop the wind blowing outside his hotel window? And what’s it like to be the person who the footballers keep on speed dial? Taking a rare break from their round-the-clock pampering, a few of them sat down with FourFourTwo to explain.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

“Even on my day off, I get a thousand calls. It’s endless”

“You can do a thousand things right, but one thing goes wrong and you get criticised,” says West Ham’s PLO, Tim De’Ath. “You need a thick skin, and you have to learn that you can’t please everyone at once"

Bournemouth’s PLO, Peter Barry, suggests things have been blown a little out of proportion. “I’ve got a smashing group of boys,” he says. “There’s no doubt that footballers do live in a bit of a bubble. It’s not a bubble of their own creation, but it’s there nonetheless. There are times that they just can’t do things that you or I can. But they get a bad rap. A large percentage of them are normal guys trying to do a high-pressure job.

“You have to remember that they live on the edge. Right now, there are players who think they’re certainties to stay at this club. But then suddenly, overnight, they’re gone. That’s hard. It can be a crazy lifestyle. Their family have to move to a new city. They need schools, accommodation, doctors – all that normal stuff. Their welfare is paramount. If they aren’t happy at home and their family is stressed, they certainly aren’t going to play well. Getting things right as a PLO helps the whole team. It’s an area that is only slowly becoming valued for its importance.”

Asked for a snapshot of his typical day, Barry laughs. “I’ll send you a chart,” he says. Opening the email attachment about his ‘roles and responsibilities’ is enough to bring on an immediate tension headache. Barry must co-ordinate travel for away games, tours, visiting officials, trialists and guests. He’s the guardian of visas and passports. He books hotels. He’s the first point of contact for squad members with the media, commercial teams, recruitment, community projects, finance, the PFA, Premier League and FA. He liaises with the chairman and chief executive. He sorts out rentals, mortgages, relocation expenses and repairs. He arranges language lessons, career development and personal issues. On matchday, he arranges ticket allocation, appearances, interviews, mascot visits and even car parking.

“You have to be a juggler, a plate-spinner, and ready for anything,” Barry admits. “You can prepare for a day, but then something completely different comes up. A plane breaks down. A dishwasher doesn’t work. It happens at all times, day and night. I don’t advertise myself as being available 24/7, but I am.”

Patience is a key asset, too. “You can do a thousand things right, but one thing goes wrong and you get criticised,” says West Ham’s PLO, Tim De’Ath. “You need a thick skin, and you have to learn that you can’t please everyone at once. You’re dealing with 28 squad members. They’ll have a puncture, or a player will call who doesn’t understand the Congestion Charge, or cannot get car insurance because companies won’t touch young footballers, or they’re on holiday and want to move hotels. Even on my day off, I get a thousand calls. It’s endless.”

Sorting out housing issues happens at the start and the end of the season but travel, communication and welfare issues occur all year round, adds Barry. “I even help out with weddings,” he says. “We have had four this summer, so I’ve been dealing with suits, cars, organists, making sure the church is booked...”

Life is unpredictable. Nothing, for example, could have prepared him for the bereavement that Harry Arter and his partner went through in 2015 after losing their baby daughter.

“It completely blindsides you,” says Barry. “It was tragic and it needed to be handled very sensitively. But we all pulled together – the players, wives, manager and staff. We pointed Harry to someone who had expertise in the field of bereavement, and our club chaplain did a great job. There was a general feeling of ‘right, Harry and his girlfriend really need us now’. Family came first and football second in that situation. It affected everyone. It still makes me emotional now, but we protected him, and the group stayed tight. I’m sure it helped them get through it.”

“I’ll get players calling to say: ‘The lights won’t come on’

McClelland went on to face the full gamut of PLO challenges, including an individual who called petrified from his hotel, convinced that it was haunted because the bed had been made while he was out

PLOs are a relatively new breed – many clubs still don’t have them – and if some think they’re a scourge, we can blame another favourite English whipping boy: Graham Taylor. In 2002, the then-Aston Villa boss created the position to help look after Juan Pablo Angel’s wife and son, who both became ill after the player moved over from River Plate to the Midlands. Lorna McClelland got the gig. “Graham was influential,” she said at the time. “He understands the layers that make up a footballer, and he knew that good support can prevent homesickness and anxiety, thus a player can perform well.”

McClelland went on to face the full gamut of PLO challenges, including an individual who called petrified from his hotel, convinced that it was haunted because the bed had been made while he was out.

It’s a typical example of player naivety. “A young lad phoned me once and said – and these were his exact words – ‘There’s a rat in my kitchen; what am I going to do?’” Wolves PLO Paul Richards tells FourFourTwo. “I collapsed laughing. Of course, he’d never heard the [UB40] song, although everyone sings it at him now. It wasn’t even a rat; it was a tiny field mouse. He had a rural property, and we explained that this would happen if he left his doors open.

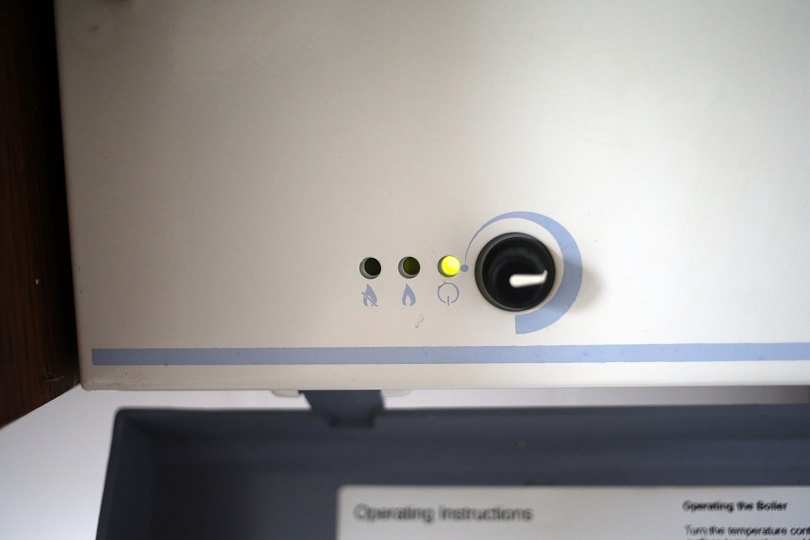

“I’ll also get things like: ‘The lights won’t come on’. And, of course, the bulb has gone. Or the kettle isn’t plugged in. But you need to remember that these are often young kids who have been in the football system since they were nine. The club want to keep them, so that they are guided through life, and they don’t need to learn about regular things. They get better with time, though. With most of them, you only have to show them once.”

Nadia McAulay is entering her 10th year as a PLO at Sunderland, and says that the arrival of a new manager usually causes the biggest upheaval. “They have different ways of working, and like to recruit from different areas of the world, so you’ll end up with individuals from new cultures,” she says.

“The key thing is to get to know them. I sit down and find out whether they’re married, if they have kids, what’s important to them. They may want a city apartment, or a village and private education for their children, or they may want to locate a mosque. I tend to accompany them to look at places.

“You learn not to assume anything. I had a foreign player who spoke great English, but couldn’t write it, which was an issue when he made out a cheque or filled in forms. As you learn these little things, it makes dealing with welfare easier.”

McAulay’s even become a plumbing expert. “‘I’ve got no hot water’ is such a common complaint,” she says. “They probably don’t know what a boiler is, let alone where it is. It’s got to the point that I will know their apartment in my head, so I can guide them to the boiler and get it fixed over the phone.”

Such is the mundanity of many situations, says McAulay, that she often forgets she’s dealing with a celebrity: “I’m around them all day, so I end up thinking about them as work colleagues. It’s only when I see a starstruck child who wants a photo that it hits home that they're idols.”

The position is, in many ways, the modern equivalent of the old-school ‘fixer’ – who was often the club manager themselves, or one of their close staff. “We’re just taking issues out of the manager’s hands, really,” says De’Ath. “It’s about making their life easier so they can focus on football.”

For Richards, a former policeman, it’s social media that has changed his job the most. “Footballers are under a microscope,” he says. “They’ll retweet something innocently, but if you look behind the tweet, there might be a group of people they shouldn’t be associated with. We need to be on top of what they’re doing on Twitter, Snapchat, Periscope – and who they’re following.

“You’ve also got them being put up on the internet by fans. What looks bad in a picture might not be the reality. And it’s especially difficult after the team lose. Suddenly you’ve got a photo of a player in a nightclub. They might just want to go out and forget about the game, but fans are passionate and ask why they’re socialising when they should be at home re-running the game in their heads!

“We’ve all had pictures where you don’t look your best – and a photo might be months old, anyway. But they have lives, and the right to some downtime.”

“The players say I’m like a dad to them”

It’s excellent when someone comes to West Ham, maybe unable to speak English, but they learn the language slowly and in a few months’ time they thank you for everything that you’ve done

Amid such 24/7 madness, why be a PLO, whose salaries are rarely above £50,000 per year? “It’s the buzz of being in football, of looking after people, and seeing those people that you have helped doing well,” says De’Ath.

“Take someone like Dimitri Payet, who has been such a pleasure to deal with. It’s excellent when someone comes to West Ham, maybe unable to speak English, but they learn the language slowly and in a few months’ time they thank you for everything that you’ve done. It’s very rewarding. And the players are great. I have never met one that I didn’t like.”

McAulay agrees. “When you get a parent coming over, saying: ‘Thanks for looking after our son so well’, it really means a lot. They’re generally all lovely guys. In 10 years doing the job, there’s only been one player that I would never work with again.”

For Barry at Bournemouth – a father of three – being a PLO is very similar to being a parent. “Some of the lads do say I’m like a dad, and that’s a real compliment,” he says. “PLOs tend to be above 40, with some life experience. The rise of this club’s been ridiculously quick, and we’ve all been through a lot together. So I appreciate it.”

Losing the dressing room: empty cliché or a real-life phenomenon?

Wiki Geeks: Meet the men keeping football's Wikipedia pages up to date

The long read: Guardiola's 16-point blueprint for dominance - his methods, management and tactics

And McAulay insists that the en-masse slamming of English players as unintelligent is a cliché, too: “It’s unfair,” she says. “We've got a lad with an honours degree in our squad. They are all different.”

Perhaps, then, if the people who bear the brunt of the problems footballers face, and who work with them day in, day out, have nothing but praise and affection for their employers, we should be slower to condemn all footballers as spoilt brats? After all, that Goma goldfish story was, in fact, no more than a prank.

“Alain thought it would be funny to ring up and say that,” explains Fulham’s Mark Maunders. “I replied that he’d have to wait, because I was out walking the terrapins. The press jumped straight on the story, using the angle that footballers are all mollycoddled, but it had all been a joke.”

Just don’t tell Danny Baker and Chris Waddle.

This feature originally appeared in the September 2016 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe!

Nick Moore is a freelance journalist based on the Isle of Skye, Scotland. He wrote his first FourFourTwo feature in 2001 about Gerard Houllier's cup-treble-winning Liverpool side, and has continued to ink his witty words for the mag ever since. Nick has produced FFT's 'Ask A Silly Question' interview for 16 years, once getting Peter Crouch to confess that he dreams about being a dwarf.