Shah vs Ayatollah and queues at 5.30am: Why Esteghlal vs Persepolis is more than a game

A country caught in the shadow of political unrest, football is Iran's escape. For the July 2009 issue of FourFourTwo, Ben Lerwill attended their biggest football derby - including "only" 95,000 spectators, and a lot of armed police...

Early afternoon, the Embassy of the Islamic Republic of Iran, London. The waiting area is warm and full of fidgety visa-hopefuls. Naturally enough, the room feels foreign. Chandeliers dangle next to banners embroidered in Farsi. Two clocks look out from the wall – one gives the wrong time in London, the other the wrong time in Tehran.

Eyes, however, are focused elsewhere. Above the windowed counter, a large widescreen TV beams out live league football from the fatherland. Every face present stares up at the game. Men in smart shirts stick their heads in to check on the score and josh each other. For the hour or so that FourFourTwo is there, attention barely wavers from the screen.

When FFT is able to leave, we walk to the string of Persian grocery stores on High Street Kensington and fall into conversation with Kamran, a twenty-something shop assistant marooned behind a bank of nuts and sugared pastries. An Iranian flag stands by his till.

Iran loves its football, man. Esteghlal and Persepolis: There’s a lot of football in the world, but that game does not compare

We talk about his native country. I tell him I’ve just come from the Embassy, and they were showing a game. “Sounds right,” he smiles. “Iran loves its football, man. But the big one’s in a couple of weeks. The two Tehrani teams. Esteghlal and Persepolis.”

When I explain that I’m travelling out to watch it, his eyes bulge. He apologises to the customer he’s serving and strides over to shake my hand. “Man, that game! I’ve been twice and I’ve never seen anything like it. I’m serious. There’s a lot of football in the world, but that game…” He pauses to find the right words. “That game does not compare.”

A derby which extends beyond the city

Almost 3000 miles away, a vast city lays spread at the foot of the snow-capped Alborz Mountains. Tehran is home to one of the fiercest and most controversial football rivalries in Asia. Iran’s Persian Gulf League has 18 clubs and in terms of popularity, 16 of them exist in the shadows.

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

The two that draw the light do so emphatically. Their support bases extend not just among the 15 million people that live in the city but across the entire country, the continent, even the world. If you’re a football fan in – or from – Iran, it’s almost a given that you’re either a Persepolis red or an Esteghlal blue.

Sport in the country is dominated by football. Locals need precious little excuse to bring up the 2-2 draw with Australia that took the national team to France 98. Once they got there, the 2-1 victory over (who else?) the US resulted in the biggest crowds seen since the Iranian Revolution two decades earlier.

Iran have been to three World Cups: 1978, 1998 and 2006. At Argentina 1978, they famously came friom behind to earn a draw with Scotland. When they hosted Japan in the qualifying rounds for the 2006 finals, 110,000 turned out to cheer them on, becoming that tournament’s largest crowd under any confederation. Street kiosks sell almost a dozen newspapers dedicated solely to football; Esteghlal and Persepolis both have dedicated publications.

There are two Irans. The first is a country defined by unsettling headlines, a nation embroiled in debates over nuclear armament and state-sponsored terrorism. Its president makes breathtakingly undiplomatic comments on Israel and homosexuality. Women are bound to keep their heads covered at all times in public and forbidden from attending men’s football. Liberal values are denounced by officialdom.

In the eyes of many, the country is a scowling theocracy with hardline global ambitions. Alcohol is illegal. The nightclubbing chapter in the Lonely Planet guidebook is just two words long. It reads: “Dream on.”

The second is street-level Iran, where introducing yourself as British is likely to meet with nothing more threatening than an invitation to tea. “Ah, Manchester! Liverpool!” It’s a country where genial hospitality to strangers is a way of life, where mutterings over governmental ineptitude are commonplace and where elegant girls in coloured headscarves turn heads on the pavement.

Again and again, the people you meet are charming, trusting and endlessly inquisitive. There’s a deep pride in the Shia faith and Persia’s ancient culture, just as there’s an astute awareness of outside perceptions.

The strange truth is that both faces – the cold-eyed fundamentalism and the humbling warmth – exist in full. A five-minute walk can take you from rabid anti-Western murals (sample slogan: “Let the US be angry with us and die of this anger”) to craft stalls where women in jeans sell handmade love-hearts.

Fearsomely stubbled policemen melt into goodwill when asked for directions. One of the first billboards you see on the drive from Iman Khomeini International Airport shows Michael Owen advertising watches. Axis of evil? There’s a Debenhams.

Pouring with passion

And somewhere in this odd, welcoming, traffic-clogged city runs a hot-headed football conflict: the reds of Persepolis and the blues of Esteghlal. Derby day is unlike any other in the sporting calendar. Twenty-four hours before the game, over a cup of sugary tea in a carpet shop in Tehran’s teeming bazaar, I meet with Hussein. He’s a red.

Lots of Persepolis fans don’t care about anything except beating Esteghlal. Crazy things happen when we play them: riots, match-fixing, fighting...

“What you need to understand is that lots of Persepolis fans don’t care about anything except beating Esteghlal,” he says. He has a habit of laying his palm across his breast when he talks about Persepolis. “We could be mid-table or lower, but if we win the derby they’ll be happy.

"Crazy things happen when we play Esteghlal. Riots, match-fixing, fighting. You know the government get scared by the passion of the fans? These days they only allow 95,000 to attend.” Right. Only?

The tale of the derby is tied up in the tale of the country. A quick history recap: in the middle part of the 20th Century, Iran was governed by Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, a dapper monarch fond of social reform and lavish living. Tourists were drawn to Tehran’s bars and discos, while the shah’s enemies (of which there were many, both secular and religious) saw him as a wasteful puppet of the West.

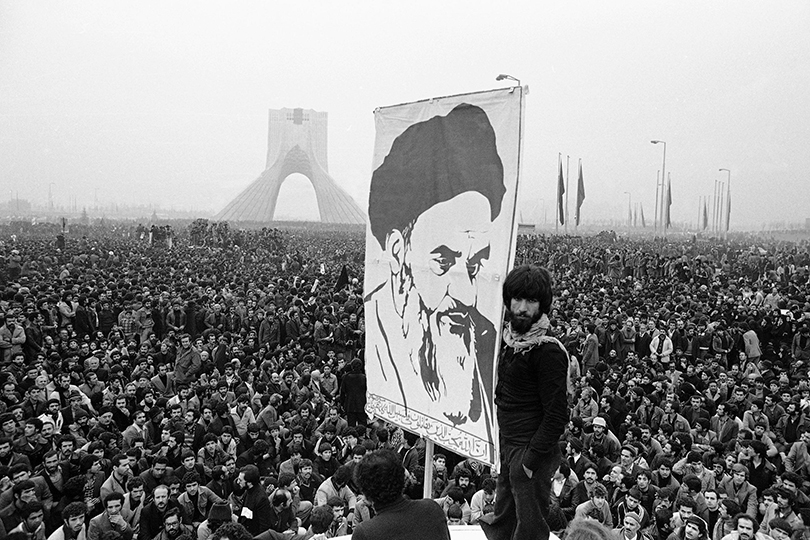

Things came to an epoch-changing head in 1979, when spiritual leader Ayatollah Khomeini tapped into public sentiment and spearheaded a now infamous revolution. The shah fled; the country became the world’s first Islamic Republic. The thirtieth anniversary of the Iranian Revolution has just been celebrated.

NEXT: How the teams reflect Iran's divisions

Here’s how the football ties in. The club that is now Esteghlal was founded in 1945 and was for decades named Taj, meaning ‘crown’. It was, in other words, the shah’s team, and became a major outfit.

The club’s name was changed to Esteghlal immediately after the revolution, when Iran’s new rulers went about purging the influence of the ousted royal family: the word ‘esteghlal’ translates as ‘independence’. The club are still traditionally seen as the team of the powerful classes; they have topped the Iranian league five times.

The blood-red shirts of Persepolis, meanwhile, have a shorter history. It wasn’t until 1963 that the club officially came into being. Their emergence coincided with the decline of the once-dominant Shahin FC, and as a bona fide rival to Taj they went on to become the working-class team of choice.

A poll carried out by a Persian television programme found that more than 60% of all Iranian football fans counted Persepolis as their preferred team. The club are therefore either loved or hated – there are few half measures. They also go by the semi-official name Piroozi, or ‘victory’. Aptly, they’ve won the league on eight separate occasions and are also the current champions.

It’s a release, a way of getting rid of your frustrations. That atmosphere – I love it. You can scream, you can sing from your heart

The first derby didn’t take place until 1968, but what the fixture lacks in long-term heritage it makes up in intensity. “It’s a release,” says Esteghlal fan Saeed, a young engineering student at the University of Tehran. He comes from a family of blues.

“It’s a way of getting rid of your frustrations. That atmosphere – I love it. You can scream, you can sing from your heart. The derby’s like a long game that’s been going on for decades. You’re down, then you’re up. You understand? There’s a history.”

Crunching the numbers

Going into this match, there have been 65 meetings between the two sides. Esteghlal have come out on top 20 times, Persepolis 16. (You might notice this leaves rather a lot of draws – more on which shortly.)

The 65 head-to-heads have not been short on controversy. Twice in the early 1970s, Taj were “awarded” games 3-0 after Persepolis refused to continue, the reds citing referee bias. In 1973, meanwhile, Persepolis walloped their opponents 6-0, a scoreline gleefully celebrated to this day – chants of “Shh-shh-shish” (“Ss-ss-six”) are still regularly audible.

A dangerously large crowd of some 125,000 poured into the ground in 1983, but more notable still were the riots of 1995 and 2000

A dangerously large crowd of some 125,000 poured into the ground in 1983, but more notable still were the riots of 1995 and 2000. The former witnessed Esteghlal pull back a two-goal deficit in the last 10 minutes, resulting in a melee of punches and a full-scale pitch invasion. The latter, which also finished 2-2, was marked by a mass on-field brawl that spilt into the stands and surrounding area. Shops and buses were trashed. Police arrested several players as well as fans.

The 1995 game is also notorious for being the last derby match in which an Iranian referee was employed – accusations of favouritism had become too widespread. Since then, the fixture has been officiated by Italians, Germans, Spaniards, Russians, Kuwaitis and Slovakians.

Until now. In a move to improve the standing of domestic officials on the international stage, the 66th Tehran derby is to be handled by Mohsen Torki, the first time for 14 years that an Iranian referee will lead the teams out.

Pre-match talk on internet message-boards is sympathetic – in a way. One fan writes: “I hope he’s sent his mother and sisters to a safe place”. Torki has other things to think about, too. The last four derby games have all finished 1-1, which has been grist to the mill of those who feel the results are being engineered to keep fans calm. Alleged match-fixing has become a hotly speculated issue, and one that the fixture has found difficult to shake off. After this game, it will prove even harder.

Tickets go on sale at 5.30am

The man selling the jester hats is bathed in moonlight and making a killing. Day hasn’t yet broken, but he and several dozen of his contemporaries – flogging everything from flags and face-paints to sandwiches and cigarettes – are doing brisk business.

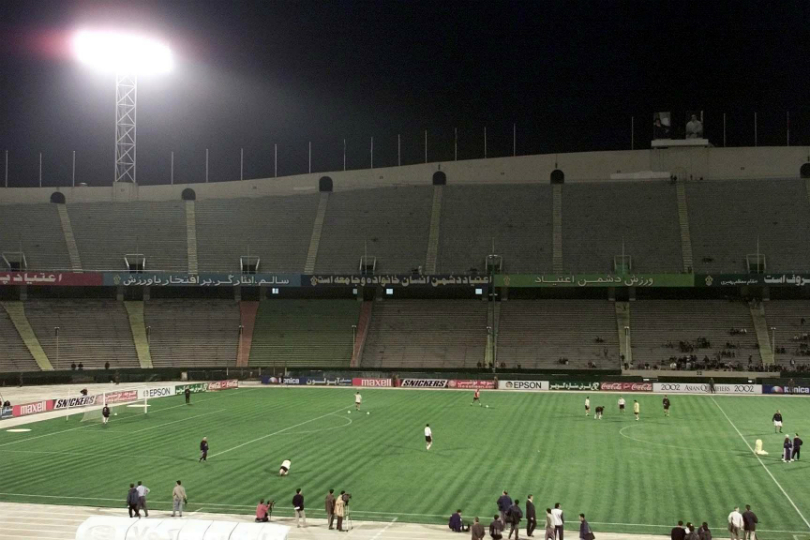

Fans file past in numbers towards the Azadi, an enormous but unglamorous lump of a stadium on the western edge of the city. It is the Friday of the game, some eight and a half hours before kick-off, and the faintest glimmer of morning light hangs above the ground. A few traders have started fires to keep warm. Armed riot police look on in the gloom.

Of all the quirks surrounding the 66th Tehran derby, perhaps the most alien to the British way of doing things is this: in a bid to counter touts and unscrupulous turnstile staff, who in years gone by have caused severe overcrowding by waving in anyone willing to slip them cash, tickets are only available on the day.

But that’s not the best part. They go on sale – get this – at 5.30 in the morning, and the vast majority of fans stay around for the day once they’ve got their tickets. At 5.45, many of those passing through the turnstiles aren’t just moving in to the ground, they’re running in.

We got dropped off by taxi at 5.30am. It’s good to get here early because you can save a spot and let the atmosphere build around you

“We got dropped off by taxi at 5.30am, but you can usually get a ticket if you arrive by 10,” says Kamyar, a blue-hatted fan joining the queues. He and his friends have just bought a silk pennant that reads ‘Esteghlal Footbool Colup’. They have a long day ahead.

“It’s good to get here early because you can save a spot and let the atmosphere build around you.” There are already small pockets of fans chanting in the dawn. “We start singing with the birds,” he laughs. It’s one ticket per person. There’s no buying them in for your mates. If you want to get in, you need to get up.

By 7am, daylight has arrived. There’s still a high moon, but the chain of mountains around the ground is visible now. A continuous stream of buses pull in, dropping off thousands of supporters not just from the city but from all over Iran – Shiraz in the south, Tabriz in the north, Kermanshah out west.

Fans cover themselves in drapes and blankets to stave off the morning chill. Anything goes: there are EU flags, Arsenal shirts and Winnie-the-Pooh rugs. One Persepolis fan wears a blue banner wrapped around his shoe – the ultimate insult.

The steady human flow runs by for hours, getting increasingly animated as the day gets warmer. Sure enough, by 10am there are 95,000 tickets sold, precisely 100% of them to blokes. That’s a lot of testosterone. All they need to do now is wait for 2pm.

NEXT: The match

The contest is nicely poised for drama. Going into the derby, Esteghlal lead the table on 52 points; Persepolis are third on 43. Both have nine games remaining. If Persepolis are serious about retaining their title, and if they want to rely on any sort of winning momentum for the run-in, this is the day to make it happen.

“Would I prefer to win the league or to beat Esteghlal? That’s hard,” ponders Amin, a middle-aged Persepolis fan whose first derby was in the 1970s. He remembers watching Liverpool-born midfielder Alan Whittle, who spent a season with Persepolis just before the revolution. “That’s really hard. When I was younger I would have said to beat Esteghlal. The dream now is always to combine both.”

First impressions of the stadium at capacity are breathtaking. If sitting around for eight hours has taken its toll on the fans, it doesn’t show. Thirty minutes before kick-off, the noise has swelled to an urgent medley of drums, horns and chanting. The panorama is split into swathes of red and blue. Persepolis fans outgun their opposite numbers by around three to two, but both sets of supporters are running their vocal cords raw.

The sun is hot now. There are flags everywhere. There are whistles everywhere. There are police everywhere. High above, soldiers stand at intervals around the entire rim of the ground while giant photos of Ayatollahs Khomeini and Khamenei preside over the whole scene. A few people perform quiet lunchtime prayers on the stadium’s outside walkway. It is a big, big ground.

Songs of praise (and hatred)

When the teams come out it is into a bowl of colour, clamour and tension. The referee looks assured. There’s a prayer, a national anthem, then the match gets underway. The stands are hung with long banners. Persepolis fans unfurl a huge flag emblazoned with the legend “The Imams Are Helping Us”.

Another reads “The Blues Are Our Servants”. On the other side of the stadium, meanwhile, the sun beats down on “Praise Be To The God That Created Esteghlal” and “Every Heart Loves Esteghlal.”

But if the painted slogans bear a kind of stirring poetry, the chants ringing around the stadium have an edgier flavour. Alireza Nikbakht, a former blue now playing for Persepolis, is greeted with a ditty that translates roughly as “The dicks of all the Esteghlal fans in Nikbakht’s mother”.

Persepolis fans respond with “Esteghlal only win trophies by giving arse”. Torki, meanwhile, attracts the nothing-if-not-creative “The exhaust pipe of an eighteen-wheeler lorry up the backside of the referee”. Charmed all round.

Referee Torki attracts the nothing-if-not-creative chant “The exhaust pipe of an eighteen-wheeler lorry up the backside of the referee”

The first half, speaking frankly, doesn’t match the billing. Obvious nerves make it a turgid affair, brightened only by a few flashes from Persepolis playmaker Ali Karimi. The crowd have become eerily muted. Half-time entertainment comes courtesy of a man in a suede jacket singing “Peace Be Upon The Martyrs Of The Revolution”.

Then, in the 56th minute, bedlam. Esteghlal break down the left, the ball is slipped to Iranian international Mojtaba Jabari and a first-time shot squeezes inside the post. The blue half of the Azadi explodes.

The next half-hour is fiery stuff. Fans barrack the referee, the players and each other. The Persepolis support become increasingly jittery – they’ve been here all day and want a result to show for it. With minutes to go, Esteghlal striker Siavash Akbarpour is presented with a simple one-on-one. It should be game over. He skies it.

And as the clock rolls into injury time and desperation sets in, a Persepolis corner finds Karimi’s head, which in turn finds the outstretched hand of Esteghlal’s Ali Alizadeh, substituted on minutes earlier. It is a plum penalty. The referee has no option. It is slotted home and the final whistle blows. For the fifth time running, the Tehran derby ends a goal apiece.

The flags left flying are red. Esteghlal fans begin ripping up seats and hurling them onto the pitch. Police rush sections of the crowd to calm them and, inevitably, skirmishes spill outside. While the vast majority of fans restrict their emotions to vocal expression, there are numerous arrests for violence (as many as 100, according to the next day’s press).

“We want football, not politics”, goes up a chant. On the main road back into town, groups of youths on scooters square up to each other. In the eyes of the fans pouring home – particularly the blues – there seems little doubt they’ve been had.

There’s always a late equaliser in the derby. A guy comes on and two minutes later there’s a handball like that? And the missed one-on-one? There was a lot of trouble after the last match that didn’t finish drawn, so for me, yes, it’s arranged.”

The media fall-out begins in force the next day. Almost all papers splash with a photo of the handball, and headlines are accusatory. Iran Varzeshi leads with “The gift – a bouquet of flowers from Ali Alizadeh”. Donya Futbol reads “Alizadeh: the special envoy for the derby”, and Navad says simply: “Inevitable”. So was it pre-arranged?

“To my mind, yes,” says Salar Vafaian, a writer for PersianFootball.com. “There’s always a late equaliser in the derby. I mean, a guy comes on and two minutes later there’s a handball like that? And the missed one-on-one? Akbarpour’s usually a good finisher. There was a lot of trouble after the last match that didn’t finish drawn, so for me, yes, it’s arranged.”

Not everyone agrees, of course – the papers are full of managers and players denying any funny business and internet message boards are split between those angrily denouncing a “clown show” and those who feel a fix sounds too far-fetched.

I meet again with Saeed, the philosophical Esteghlal fan, the day after the game. Looking down at the front pages on the newsstands, he gives the final word. “The derby’s bigger than the result. If it’s being arranged, that’s terrible for the league and for the country.

"But I like to think it’s honest. The passion of the fans won’t go away, the derby won’t go away. I guarantee that next season, early morning, we’ll all be back. It’s too big.”

This feature originally appeared in the July 2009 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe!