Southampton feed England's bloated big boys, but how long can they dine fine themselves?

Southampton have seen their top talent snatched away by the Premier League's big guns far more than most clubs. Alex Hess explores the science behind the Saints' balancing act, and considers whether they can sustain their success

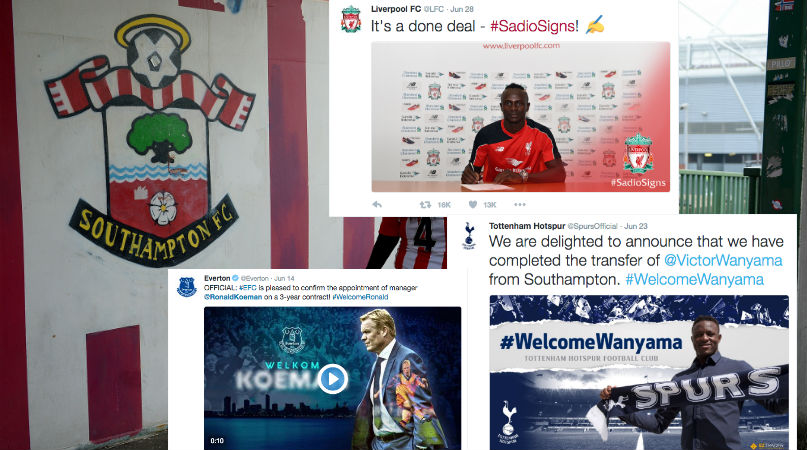

“West Ham’s our feeder club,” they used to sing at White Hart Lane, and for a time they were right. Right now, a similar bond has emerged between Liverpool and Southampton, although there have been few songs breaking out on the Kop to celebrate the matter. If Southampton is indeed their feeder club, Liverpool have spent three years gorging themselves into slothful stupor.

A recent history

The notion of a 'feeder club' – in this informal, mocking sense – implies a power imbalance; economic Darwinism in full and ruthless effect. As sung heartily in north London, it happened in the capital around the mid-noughties when Jermain Defoe, Frederic Kanoute and Michael Carrick all made the short trip from West Ham to Tottenham at a time when the latter were establishing themselves as an upper-mid-table force and the former were yo-yoing between divisions.

An even starker example occurred a few years later, when Manchester City’s megabucks takeover coincided with the era of uncompromising belt-tightening at Arsenal and acted as a prelude to no fewer than five first-teamers migrating north in as many summers. Accordingly, City won four major trophies during that time, clambering up English football’s hierarchy, while Arsenal – once the country’s dominant force – made do with one. (The mini-exodus of Arsenal players to Barcelona around the same time – five players in the eight years between Thierry Henry and Thomas Vermaelen’s transfers – could also be seen similarly.)

The case of Southampton and Liverpool is at once more clear-cut than both of these and far more nuanced. The recruiting of Sadio Mane to Anfield – after Nathaniel Clyne’s move a year ago and the Rickie Lambert-Adam Lallana-Dejan Lovren triple-swoop 12 months before that – takes Liverpool’s south-coast shopping habit to five players in just three summers.

On the face of it, then, it’s business as usual; the richer, more powerful club hoovering up the most impressive performers from the club a rung or two below, bolstering its own squad while making sizeable dents in that of its most immediate pretenders’. Except that’s where the blueprint ends. Because while the economic relationship between the clubs may adhere to convention, Liverpool have wholly failed to see a return on their investments in the currency desired: Premier League points.

Bucking the trend

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

A quick glance at the division’s final standings over the two seasons during which Liverpool have been doing their plundering does not tell the story of a big, brawny fish stuffing its face with a minnow. Instead it shows the minnow resisting consumption, administering a slap to the face of its larger relation, and accelerating away into the distance.

The season immediately after their three star players moved to Merseyside, Southampton made up 26 points and five places on Liverpool; one year – and another big-money transfer – later, and they’d made up another five points to leave their looters, now eighth in the table, gazing upwards in their direction come the season’s conclusion.

The first instinct is to point and laugh, which is of course a fair response; schadenfreude is at the heart of human nature, and, as proven by Dr Evil and David Moyes, watching power exercised blunderingly is one of life’s great pleasures.

The alternative answer however is that Liverpool are not doing very much wrong at all. All four of their buys – five if we include Mane – looked sensible at the time

But another reaction is to ask: "What exactly are Liverpool doing wrong?"

Well, the traditional bingo card tends to include the terms ‘Brendan Rodgers’, ‘Transfer committee’, ‘Moneyball’, ‘Weight of expectation’ and ‘Luis Suarez’, so take your pick from the above.

The alternative answer, however, is that Liverpool aren't doing very much wrong at all. All four of their buys – five if we include Mane – looked sensible at the time, and only the least expensive, Lambert, has been an outright failure.

Indeed, the others have been three of the standout performers of Jurgen Klopp’s nascent reign. And, as a certain superclub just down the M62 has shown over the years, poaching the best players from the clubs just beneath is a tried-and-tested means of asserting and reasserting dominance. Liverpool have been helping themselves to Southampton’s players at a time when the two clubs have passed each other at a crossroads, but correlation needn’t equal causation.

Defying gravity

Look beyond the bigger club, though, and there’s another, more significant story at work here. Namely, Southampton’s apparent ability to defy gravity; to remain upwardly mobile while being routinely disembowelled by football’s moneyed vultures. Because lest we forget, as well as the annual defections to Anfield, three more of Southampton’s most brightly glistening gems – namely Luke Shaw, Calum Chambers and Morgan Schneiderlin – have also been hoisted up the food chain and away from St Mary’s in the past two years.

That they’ve avoided sinking like a stone is, by the standards of modern football, a feat of survival akin to that famous Buster Keaton scene with the falling house. To have actually improved on their league position year-on-year since promotion (14th, eighth, seventh, sixth) makes a compelling case for the most impressive long-term project in England’s top flight.

Southampton’s secret? There isn’t one. They just spend thriftily, recruit smartly and ensure that the club’s overriding model remains coherent and unaltered. All of which is, of course, precisely what every club claims to do – it’s just that at Southampton, they actually do it.

The term ‘philosophy’ has become near-ubiquitous of late, but the Saints are one of the few clubs who can use it sincerely. When Lovren, Lallana and Shaw were lost to the wealthy elite, Dusan Tadic, Virgil van Dijk and Ryan Bertrand were picked up from either low-key European leagues or the big-club scrapheap, and with £40 million of profit in the bank for good measure.

It’s a carousel that’s been whirling steadily in recent years: lose Lambert, sign Graziano Pelle; lose Schneiderlin, sign Jordie Clasie; lose Clyne, sign Cedric Soares. Again, there’s no magic formula to any of this. Southampton’s scouts are not unearthing unknowns for a pittance, just indulging their capacity for shrewd and thorough scrutiny of any prospective purchase. Gaston Ramirez and Dani Osvaldo are proof there’s no crystal ball involved, and that each signing is merely a calculated risk.

If there is a running theme, it’s the readiness to discard the ‘proven Premier League player’ component from their equation. Four of the above names were recruited from Portugal and the Netherlands, with others coming from Strasbourg, Salzburg and Celtic. All of which leaves a delicious irony in that so many of their players, after proving themselves capable in England’s top division with a stint at St Mary’s, have gone on to struggle meekly at other Premier League clubs.

All about the Mane, Mane, Mane...

The real question, as Mane follows Victor Wanyama and Ronald Koeman in slinking out of Southampton's eternally flapping exit door this summer, is about how sustainable a model it is. In a world where information is so ludicrously accessible, how can one club continue to fly under the radar, to swoop unchallenged for their targets and to raid everyone else’s junkyards for undiscovered gold?

Southampton have gone about quietly tying up a couple of distinctly Southampton-scented deals: for Nathan Redmond, the young, skilful, but never-quite-hit-his-peak winger from recently relegated Norwich; and for the experienced coach Claude Puel

Time will have to tell. But the answer to Southampton’s continued survival, counterintuitively enough, may lie in their competitors’ steeply increasing financial might. With the effects of the Premier League’s new TV deal now in full force, England’s clubs are truly swimming in cash. And, as a quick glance over Michael Bay’s back catalogue illustrates, the one thing guaranteed to discourage innovation is a tidal wave of money. After all, why raid the Portuguese league for dicey rookies when you could go out and buy Yohan Cabaye from PSG or Xherdan Shaqiri from Inter – or Sadio Mane from Southampton.

In theory, the cash flood should leave Southampton free to practise their tried-and-tested methods unperturbed. Indeed, they’ve already been doing so: amid this summer’s noisy scramblings for the signatures of Carlos Bacca, Alexandre Lacazette and the rest, Southampton have gone about quietly tying up a couple of distinctly Southampton-scented deals. Already they've signed Nathan Redmond, the young, skilful, but never-quite-hit-his-peak winger from recently relegated Norwich, as well as the experienced coach Claude Puel, who’ll be manning the dugout next term after being headhunted from Nice.

Redmond scores in the 2015 play-off final

There may yet be more losses; Van Dijk’s splendid form last season might just have been a bit too splendid, depending on which clubs are in the market for a centre-half in the coming weeks, while Pelle’s outings spearheading Euro 2016’s outstanding side have made him an even more handsome prospect than he was before, and to a continent of onlookers.

But if the vultures start swooping once again, don’t presume it will spell the end for Southampton’s own ascent. They may well be a feeder club, but they’ve learned how to feast like kings.