Splitters, shooters and Sowetan pride: Why Kaizer Chiefs vs Orlando Pirates is more than a game

It may only be 40 years old, but the Soweto Derby is one of the fiercest around – and it's no friendly... as Andy Mitten found out for the November 2008 issue of FourFourTwo...

A policeman bangs his knee as he struggles to climb onto a riot van roof clutching a loud hailer. The pain adds to the frustration in his voice. “Don’t push forward,” he shouts, his words barely audible above the non-stop shrill of vuvuzela horns which create a uniquely African atmosphere.

Beneath him, a dangerous, swelling crowd of Kaizer Chiefs and Orlando Pirates fans crowd around a temporary ticket checkpoint. The policeman’s pleas are ignored. “I don’t know why he speaks in English,” says a concerned news photographer, “these people speak Xhosa.”

I don’t know why he speaks in English, these people speak Xhosa

With just one main checkpoint for 30,000, the crowd pressure continues to build until several crush barriers buckle and twist to the floor. Screaming, frightened fans are pulled free. Others take advantage of the panic and run for the turnstiles, while some blow into instruments which produce a plaintive, unsettling sound like a baby crying.

“I nearly died!” hollers a hysterical Chiefs fan as she’s helped to her feet by a Pirates supporter, but the majority are unfazed by the crush. Their nonchalance is surprising, especially given that fans of these Sowetan giants, by far the biggest clubs in South Africa, were involved in a stampede which led to the death of 43 fans at Johannesburg’s Ellis Park in 2001. A decade earlier 42 fans died in similar circumstances when the two teams met for a pre-season friendly in Orkney, a provincial town 125 miles from Soweto.

South Africa has the world's second highest homicide rate, you're 40 times more likely to be murdered than in Britain and rape levels are the highest on the planet

It’s no surprise then, that safety and security are the main issue facing South Africa as they prepare to host the 2010 World Cup finals. The country has the second highest homicide rate in the world after Colombia, you are 40 times more likely to be murdered in South Africa than Britain and rape levels are the highest on the planet.

And that’s not all. “I have serious reservations about policing for the 2010 World Cup,” says a security guard on spotting FourFourTwo’s media pass. “Police here react to any problems with pepper spray. Write that.”

Two teams, one country

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

While rugby is easily the most popular sport among South Africa’s four million whites, football is undoubtedly the major passion of the other 42 million. And such is the popularity of the two biggest teams that the rivalry between them divides the whole nation, not just their home city.

“Chiefs and Pirates can meet anywhere in South Africa and there will be a huge crowd,” says football agent Glynn Binkin. “Both have fans all over the country and that’s why games have been played in Durban or Port Elizabeth on the Indian Ocean, which is at least five hours from Soweto."

We’re in ‘PE’ for tonight’s game, which although only a pre-season friendly, carries a reward for the winners of a game against Manchester United in the final of the Vodacom tournament. With the Nelson Mandela Bay World Cup Stadium in the seedy north end of this city of 740,000 behind schedule, the game is being held in PE’s main rugby stadium in a middle-class white area just a mile from FFT’s hotel on the palm-fringed seafront. Throw in the fact that PE is dubbed ‘the friendly city’ and shanks’s pony seems the most viable transport option for tonight’s game. The hotel receptionist has other ideas.

That’s not a good idea. It’s not safe for a lone white boy

“Where are you going, Sir?” she asks.

“I’m walking to the football game.”

She looks aghast. “That’s not a good idea. It’s not safe for a lone white boy.”

“It’s ten minutes to walk,” I reassure her. “I’m carrying nothing but my match ticket.”

“It’s not safe,” she insists. “Best to drive and park as close as you can to the stadium.”

The main road which links the ocean, airport and stadium has been blocked by the ticket check so I drive a little before joining the fans making their way to the match. Some dance and move slowly, others sing and perform a rhythmic, almost hypnotic hopscotch movement which gradually takes them closer to the four giant floodlights. I feel conspicuous as the only white person, but that paranoia will evaporate by kick-off, which is still two hours away. Time for a bit of background.

“This is where the madness happened, that’s where the Chiefs and Pirates fought,” says Lucas Radebe, pointing at Soweto’s vast FNB stadium in the shadow of an old goldmine slagheap – hence the miners’ helmets worn by both sets of fans. The FNB will be renamed ‘Soccer City’ and will host 2010’s opening match and World Cup final. Currently under reconstruction, a new roof and extra tier will boost the capacity from 70,000 to 95,000.

Unfortunate trouble

A township of around four million, Soweto sits like a colostomy bag, detached but linked by necessity to the economic hub of nearby Johannesburg. It is where Nelson Mandela and Archbishop Desmond Tutu have houses on the same street, the only one in the world housing two Nobel Peace Prize winners, and where Radebe grew up.

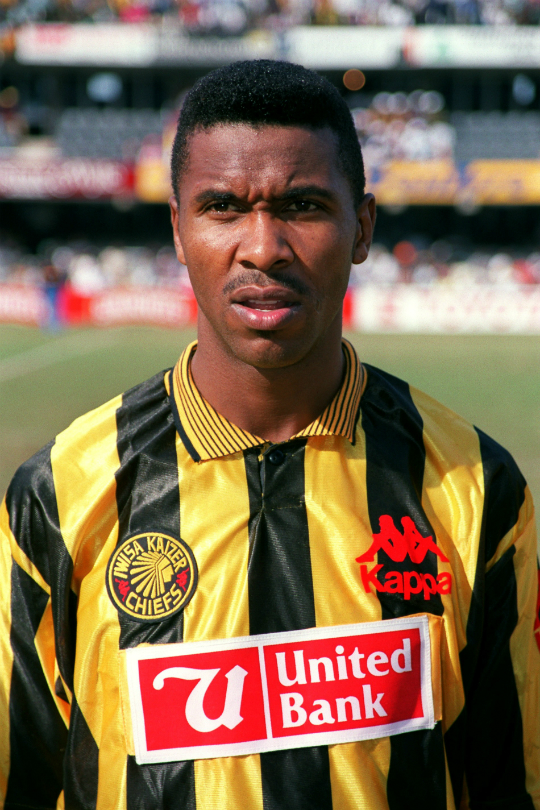

The former captain of South Africa was an Orlando Pirates fan who played for Kaizer Chiefs before joining Leeds United in 1994. He was such a hero at Elland Road that the Leeds-supporting band named themselves after Radebe’s former club – though they spelt it ‘Kaiser’.

“Sowetans love football and the rivalry was fierce between the Amakhosi (Chiefs) and the Pirates,” recalls ‘the Chief’. “The build-up would start in the township weeks before the game. Fans would bet illegally on the result and taunt each other.

"The derby even divided families – like mine where I was one of 11. I was Pirates and some of my brothers were Chiefs. I could never watch a game with them. Matches would sometimes be abandoned because of the trouble – though it was more against the authorities than among rival fans.”

At 15, Radebe was sent to Boputhatswana, a black independent homeland in northwest South Africa, by his concerned parents. “There was a lot of violence in Soweto and no proper education,” he explains.

“I was getting into a lot of mischief with my friends and we would take government cars from people. I carried a knife, we’d stop them, tell them to get out and take the car. Then we’d burn or vandalise it or sell it for scrap.”

Radebe played football as a goalkeeper for “something to do” in Bophuthatswana, later moving to outfield where a Chiefs scout spotted him. Professional terms were offered, but his mother was unconvinced.

“Mum didn’t want me to play football,” says Radebe, “she thought it was an excuse to party and sleep with different women. She eventually gave in on the condition that I studied too.”

NEXT: "This is where I got shot"

Radebe joined the Chiefs in 1990, the year Nelson Mandela was released after spending 27 years in jail, and soon played in his first Sowetan derby. “The memory sends shivers down my spine,” he recalls.

“I was living at home, sleeping on the kitchen floor and everyone recognised me in the area. It was a big deal for a township boy to play for the Chiefs and even Pirates fans would come to my house to for a chat before the game.”

It was the players who caused him problems. “Some from both sides were proper thugs,” explains Radebe. “They carried knives and hung around the streets after games. They tried to intimidate me and demanded, ‘Let us win or we will beat you up’.

"I wasn’t intimidated, coming from where I did. I’d grown up witnessing violence and tension in Soweto between the different tribes. I’d seen real hatred against the police and a lot of them were killed. So were any informers. They were helping the government, which people were against under apartheid.”

Radebe is still recognised everywhere. His luxury car is conspicuous among the poverty of Soweto and fans make signals to him – crossing their wrists to copy the Pirates’ skull and crossbones badge or giving the ‘V’ for victory sign to denote Chiefs’ allegiance.

He drives to the district of Orlando, where more Pirates fans recognise him, but they are reverential toward a man who captained Bafana Bafana in the 1998 and 2002 World Cup finals and once came second to Mandela in a poll of the most respected South Africans.

We pass the sprawling settlements of immigrants where there is no running water or electricity. And his old school, where a cow has been tied to a lamppost painted in African National Congress colours, awaiting slaughter. We meet old school friends, all of whom look 10 years older than Radebe, and visit his old house.

This is where I was shot in 1991. To this day I don’t know why. I felt a pain in my back and saw blood...

“This is where I was shot in 1991,” he says quietly, pointing to the street outside the house where a brother still lives. “To this day I don’t know why. Maybe someone was hired to do it so I wouldn’t leave the Chiefs. Punishments were common then.

"I just remember hearing gunfire and looking around to see who had been shot. Then I felt a pain in my back and saw blood. I was taken to hospital and lost a lot of blood but luckily no vital organs had been hit.” The bullet passed through Radebe’s thigh. He could play football again.

An icon creates a rival

Despite its ferocity, the Sowetan derby is relatively new. The Pirates, South Africa’s oldest club, were formed in 1937 by the offspring of migrant workers who moved from rural areas to work in the gold mines.

Playing in the State taught him that football could be far more professional. He changed his mind: ‘Kaizer’s Chiefs’ would continue

Radebe was just nine months old when former Pirates player Kaizer Motaung formed a new club which took his name in January 1970. Born in Orlando, Motaung left Pirates for a successful career in North America with the Atlanta Chiefs before returning to South Africa where he discovered that four of his close former team-mates had been expelled by the Pirates.

Using the banished players, Motaung set up his own all-star XI to play in friendly matches, though he never intended for this to be permanent, considering it a betrayal to the Pirates. But having seen the success of the friendly matches and the positive reaction of the crowds who considered them a football equivalent of the Harlem Globetrotters, Motaung gave his idea more thought.

Playing in the States had taught him that football could be far more professional and he was keen to apply his know-how in South Africa. Influenced by his father, friends and the former Pirates players, he changed his mind; ‘Kaizer’s Chiefs’ would continue.

While they could not have expected Pirates to welcome the rival set-up, Motaung’s decision was made easier by the Pirates’ apparent dismissive attitude and arrogance. Emboldened, the Chiefs began to poach players from the Pirates under the auspices of playing for a ‘more professional club’.

If you defeated Pirates at Orlando Stadium, chances were that it would be difficult to leave the stadium unharmed

“Kaizer Chiefs was formed at the right time,” says Motaung. “We were living through a politically repressive and violent era. If you defeated Pirates at Orlando Stadium, chances were that it would be difficult to leave the stadium unharmed. Then along came Chiefs. Our dress code (black and gold) appealed to a lot of people. Maybe that is why we had such a large number of women supporters. We also promoted the concept of love and peace.”

The Pirates didn’t quite see it like that. Cast as “rebels”, the Chiefs were admitted to South Africa’s top black league in 1971 and won their first national title in 1974 with Motaung as manager. He still runs the club he started 38 years ago. Jomo Sono, another former Pirates player who moved to the American NASL, also started his own club: Jomo Cosmos, who also play in the top flight.

While their record defeat was a 5-1 loss to Pirates in 1990, Chiefs boast a better head-to-head record against their foes and have won five more league titles. The Pirates, though, remain the only Southern Hemisphere club to have won the African Champions League in 1995.

The PA system plays a continuous stream of house music and most fans dance along. It’s like Pacha in Ibiza at 5am, but without the drugs

While the Chiefs are known as ‘the Glamour Boys’, the Pirates – who are known as ‘The Happy Club’ and ‘the Buccaneers’ and their fans as ‘The White Ghosts’ – "are more rural and poorer,” says agent Glynn Binkin, “and the Chiefs probably shade it in terms of numbers.”

A clubbing atmosphere

It seems that way tonight in Port Elizabeth, as the 30,000 cram inside the ageing stadium, many of them die-hard fans who have main the train journey from Soweto. The public address system plays a continuous stream of house music and most fans dance along. It’s like Pacha in Ibiza at 5am, but without the drugs.

Fans from both clubs bounce around in unison without segregation. Although the rivalry is fierce, hooliganism is not a major feature. The authorities, as Radebe says, have provided the historic enemy.

Some fans sport outlandish costumes – personalised miners’ helmets, horns, badge-covered butchers’ coats similar to those worn on the Stretford End in the 1970’s, plus outrageous plastic glasses. Like Colombia’s birdman, the fans are available for hire and opposing fans put aside differences to appear in adverts together, their hats carrying the logos of mobile phone companies.

Despite the lack of anthemic terrace chants, the atmosphere is vibrant, with virtually every fan dancing throughout the game. For reasons known to himself, one man walks around the terraces with a giant inflatable baby’s dummy, while another, to general applause, brandishes a placard saying “No one can stop us Sowetans”.

At half-time, an enormous lady in bulging Lycra pants spills onto the pitch flanked by two gorgeous dancers. She does the splits, gyrates and dances, strutting her stuff magnificently and the crowd love it.

Aside from FFT, the referee and the two imported coaches – Dutch legend Ruud Krol at Pirates and the Chiefs’ Turkish manager Muhsin Ertugral – the only other white person in the stadium appears to be the 19-year-old Pirates midfielder Michael Morton. “For us, playing against Chiefs is a motivating factor in itself,” he says. “We hate to lose against them.”

Unfortunately, his fears are realised as the Chiefs dominate to win 2-0, with their Player of the Season scoring the second goal for his dad’s side. They go on to meet Manchester United in Pretoria where a sell-out crowd of over 50,000 sees them beaten 4-0.

NEXT: "There was a Foreigner XI, a white XI, a black XI and an Indian XI"

The future looks bright for South African football, largely thanks to the investment and rising crowds brought about by the World Cup. Apartheid and segregated and breakaway leagues are a fading memory as the country’s four main racial groups – black, white, Indian and ‘coloured’ (‘mixed race’ in the UK, but slightly more complicated in Africa) – are represented in the ABSA Premiership.

'Coloured' players have tended to be the best, identified by their European surnames like McCarthy, Pienaar, Bartlett and Fortune. Though much of their development happened outside of South Africa, they are homegrown, a situation which contrasts with 40 years ago when fading British stars were imported to play in a white-only league.

Player development

“Guest players like George Best, Johnny Haynes, Jess Astle, Bobby Moore and Derek Doogan came,” explains Paul Mathews, whose father Roy played 161 games and scored 52 goals for Charlton Athletic between 1959-67. “My dad moved here and was placed in a Foreigner XI. There was also a white XI, a black XI and an Indian XI – it was all a bit confusing.”

There can be 70,000 for a Soweto derby, but at the other end of the scale you can get crowds of 150 for a top-flight game at Witts University

“Now, there’s one league and the best supported teams are the Chiefs, Pirates and Mamelodi Sundowns who all average between 10 and 15,000,” says agent Glynn Binkin. “There can be 70,000 for a Soweto derby, but at the other end of the scale you can get crowds of 150 for a top-flight game at Witts University.”

“What concerns me is that there’s not enough player development,” adds Binkin, of a country which sees its best players leave for Europe before they turn 18 because of a lack of serious, well organised competition at youth level.

“In terms of player development, the light at the end of the tunnel should have been 2010, yet a lot of the people involved in 2010 will leave straight after the World Cup. The people who love football will be left to pick up the pieces.”

Chiefs, who have used nine stadiums in Johannesburg as their home ground in their short history, should benefit directly as they will move into the 55,000-capacity Amakhosi Stadium 30 miles west of Johannesburg in 2010, becoming the first team in South Africa to own their stadium.

The Pirates will remain part-owners of the redeveloped 70,000-capacity Ellis Park, though they have applied to play in a new 45,000 stadium in their own Orlando suburb which, although completed and top-class, will only be used as a training venue in 2010. An indication of the different attitudes to stadium use in South Africa is that another club, Moroka Swallows, have also applied to use the new Orlando venue.

Half of the country’s 16 top clubs come from the economic hub around Johannesburg and Pretoria. This included the Sundowns, the Chelsea of South Africa, who are owned by mining entrepreneur Patric Motsepe – Forbes’ 503rd richest person in the world, no less – and have broken the Chiefs/Pirates duopoly on domestic football, winning five league titles in the last decade and attracted crowds to match the Sowetan pair, as well as paying for a full-strength Barcelona side to play an exhibition game against them in 2007.

With league success more difficult to come by, the Sowetans have focused on the cup competitions. “That sums up the mentality of many in South Africa,” claims Rob Moore, South Africa’s leading football agent. “Fans are happy with the quick fix of a cup. They like the sprint of a cup rather than the real acid test of a good side, the marathon of a league campaign.”

While Chiefs versus Pirates remains the jewel in South African football, there are growing concerns about the exploitation of its popularity.

Driven by powerful club owners Motaung and Irvin Khoza of the Pirates, both clubs co-operate out of commercial interest to attract joint sponsors. Vodacom’s logo appears on the both teams’ shirts and the mobile operator has created the pre-season competition to which clubs like Manchester United and Spurs have accepted lucrative invitations.

It means Chiefs and Pirates can play each other six times a years, the derby transported to various venues. “This has watered the rivalry down,” claims Moore. “Too much of a special thing ceases to be so special when it happens all the time.”

Try telling that to the Chiefs fans, resplendent in black and gold, loudly celebrating victory over the Pirates in Port Elizabeth.

This feature originally appeared in the November 2008 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe!

Andy Mitten is Editor at Large of FourFourTwo, interviewing the likes of Lionel Messi, Eric Cantona, Sir Alex Ferguson and Diego Maradona for the magazine. He also founded and is editor of United We Stand, the Manchester United fanzine, and contributes to a number of publications, including GQ, the BBC and The Athletic.