Squad rotation, tear gas and a bucketload of medals: How England flopped at Euro 80

Boasting 19 European Cup winners' medals, England went to the 1980 European Championships sure of success. But as Daniel Ruiz explains, things quickly fell apart for Ron Greenwood's team, with poor performances on the pitch and chaos in the stands...

As Ron Greenwood made his preparations to take his England team to the 1980 European Championship in Italy, he had good reason to feel confident. The first man to lead England to a major international tournament since Alf Ramsey's team fell to Gerd Muller's volley in the World Cup in Mexico, he could also boast a group of players, in terms of honours at least, far superior to Ramsey's 1970 vintage.

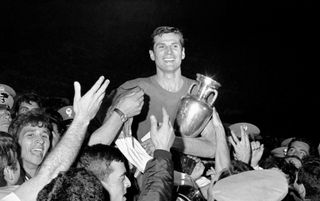

With Liverpool and Nottingham Forest providing nine of Greenwood's 22-man squad, which also included Forest old boy Tony Woodcock and ex-Anfield stars Emlyn Hughes and Kevin Keegan (the double European Footballer of the Year at Hamburg), the group boasted a staggering 19 European Cup winners' medals between them [editor's note: England's 2016 vintage have just four].

Greenwood had taken charge in the summer of 1977, arriving too late to steer England to the 1978 World Cup finals in Argentina, but had built an impressive-looking team by focusing on the fundamentals.

"Football's a simple game, you don't have to complicate it, and Ron brought that simplicity back to the national set-up," recalls Southampton centre-half Dave Watson, a survivor from the last days of the Ramsey era. Unlike Don Revie, he didn't play players out of position."

Carrying national hope

England looked in good shape. A 2-0 friendly win over fellow qualifiers Spain was followed by a 3-1 Wembley victory over World Champions Argentina.

With qualification confidently sealed from a group featuring Denmark, the two Irelands and Bulgaria, England were among the favourites to lift the trophy, but their involvement in the Championships was not top of the domestic agenda. It was a time of social and political unrest. Unemployment had moved above two million for the first time since 1935, and would rise by a further half a million by the end of the year, while the siege of the Iranian Embassy in London was gripping TV viewers worldwide.

On the sporting front too, the footballers were overshadowed by the forthcoming Olympics, and in particular, by the decision to send a British team to Moscow. The British Olympic Association was defying new Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher's efforts to back the US boycott in response to the USSR's invasion of Afghanistan the previous year.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Nevertheless, England looked in good shape. A 2-0 friendly win over fellow qualifiers Spain in Barcelona that spring was followed by a 3-1 Wembley victory over World Champions Argentina, a game that introduced a 19-year-old Maradona to England fans and players.

"He made this great run, similar to that second goal against England in Mexico 86," recalls Forest striker Garry Birtles, who made his England debut as a late substitute. "On this occasion he put it into the side netting, but we were all looking at each other on the bench, having never seen anything like it. You could see this guy was going to be a massive talent."

"Leopoldo Luque, their centre-forward, told me off for tackling him on one occasion," chuckles Watson. "He said, 'He's only a boy.' But as far as I was concerned, if he was playing, he was big enough to take a tackle."

Even a 4-1 defeat away to Wales just days later, England's heaviest since 1964, could not dampen the enthusiasm. But with the Forest contingent in Madrid for the European Cup final against Keegan's Hamburg, Greenwood was unable to field his first 11 for the rest of the Home Internationals, and the Wales loss was followed by a fortunate 1-1 draw at Wembley against Northern Ireland, and an unconvincing 2-0 win over Scotland.

Next came the nonsensical decision to send a makeshift 16-man squad to Sydney for the Australian FA's centenary celebrations less than a fortnight before the start of the championship. Of those 16 who returned home after a 2-1 victory, only Joe Corrigan, Trevor Cherry, Paul Mariner and Glenn Hoddle were included in the squad for the finals. Bryan Robson, capped for the first time in the qualifier against Ireland, was surprised to be told he was left out. Robson described the flight back from Australia as 'perhaps the worst journey I've ever had'.

Another 23-year-old was luckier. Birtles, fresh from a second European Cup success with Forest, was so convinced he had no chance of making the squad that he had gone to stay with [Forest reserve keeper] Chris Woods in Lincolnshire when he got the call telling him he was going to Italy. It would be quite some adventure.

Derby day and Downing Street

The squad spent their last days in England holed up in a large hotel in Hertfordshire, finding ways to amuse themselves as they prepared for the biggest games of their lives. One focal point became the stereo that Dave Watson insisted on taking to all England get-togethers (Steve Coppell had drawn the short straw as room-mate).

"I was a big Quo fan, but that summer some of the players would gather in my room to listen to the latest Gerry Rafferty album, Night Owl," recalls Watson, whose fabled hi-fi included not only the usual tape-deck/radio, but also a television. Eighteen inches long, six inches deep, it was so big that he had a flight case specially built for it.

Horse racing enthusiasts Emlyn Hughes, Mick Mills and Phil Thompson took their minds off things by hiring a helicopter to fly them to Epsom for the Derby.

"It was all the rage back then," he says, "and I still have it to this day."

Meanwhile horse racing enthusiasts Emlyn Hughes, Mick Mills and Phil Thompson took their minds off things by hiring a helicopter to fly them to Epsom for the Derby, where a record 400,000 crowd saw Willie Carson win for the second year in a row. "It was a superb day, one of those things you can't believe you can do," recalls Mills. "We'd just had a full training session and got cleaned up, and shortly after midday the helicopter was buzzing its way into the hotel grounds."

The players landed in the centre of the course just before the first race was due to start. "We all had the Derby winner and we had a couple of other little bets that allowed us to pay for the helicopter," says Mills. "As we waited for it to take us back, we met up with Willie Carson and had a little chat."

As they landed back in the hotel grounds, Keegan came sprinting over. "He'd been entertaining a young boy with a terminal illness, giving him a special day out where he got to meet the players. Kevin had a quick chat with the pilot and it was quickly arranged for the boy to go up in the helicopter for a spin."

The social whirl continued with a cocktail party at number 10 thrown in the squad's honour. "It was a nerve-wracking evening," says Kenny Sansom. "We were all there in our suits looking very smart and meeting the 'Iron Lady'. I was very shy back then and a little tongue-tied. On meeting the Prime Minister, what do you say?"

Watson, minus stereo, didn't seem to have a problem, finding himself on a private tour of Downing Street with the PM as guide. "She seemed to take a liking to me for some reason, and came over and took hold of my hand. Suddenly we were off on this excursion. She showed me these paintings of the ex-Prime Ministers that were hanging on the walls and gave me their history. It was very enjoyable - we didn't talk football at all."

Mills remembers being taken aback by the size of the place. "The most amazing thing is that, when you see that door on television, it looks a pretty small building, but inside it seems to take off and go on for miles."

Though the PM expressed concern about the team playing in such high temperatures, she needn't have worried. Northern Italy had been hit by four days of non-stop rain and thunderstorms, and the narrow, cobbled streets of Asti - the nearest town to where England would stay, and famous for its sparkling Asti Spumante - were awash. The squad were to stay in a small hotel perched on a hilltop; but unlike the local drink, England's finals would be anything but sparkling.

The eight qualifiers were divided into two groups of four. With no semi-finals, the top team in each group would contest the final, while the second-placed countries fought over third place. The favourites were Jupp Derwall's West Germany, rebuilt after a poor defence of their World Cup title in Argentina, and drawn in Group A alongside a Dutch side in sharp decline, holders Czechoslovakia and surprise qualifiers Greece.

Group B saw England up against Belgium, Spain and Italy, whose fans expected a repeat of the 1968 success when they had last enjoyed home advantage. But the hosts were in turmoil, with 33 players - including some internationals - due on trial in Rome charged with fraud, having allegedly accepted money to fix the results of two games.

Italy coach Enzo Bearzot threatened to resign unless his Federation told him who would be available for selection, but on May 19 he got the news he didn't want. Paulo Rossi, so vital to Italian hopes, was banned for three years, later reduced to two on appeal.

Greenwood would also be without his first-choice striker, a ruptured Achilles ruling out Forest's £1m man Trevor Francis, while Keegan's knee ligament was giving cause for concern. An exhausting season with Hamburg and endless commercial commitments had taken their toll on the England captain.

Sansom, however, was in heaven. "I remember the buzz I felt when we were all handed our identity badges - that's when you realised you were part of something. The fact that the finals were in Italy made it even bigger for me as I felt Italian football was the best in the world."

In the evening of June 12th, the streets of Turin played host to a running street battle between 200 English and Italian hooligans.

Sansom was rooming with Tottenham star Hoddle, but while Hoddle was an early bird, the Palace youngster found himself seeing out his evenings in the card school. "I was playing with the big boys," he says, "Kevin Keegan, Terry McDermott and Peter Shilton. When we travelled to the games, we just played seven-card brag for points, but back in the hotel we'd go down to three-card brag where we played for a little more."

As England relaxed, Group A kicked off on June 12 with 1-0 wins for West Germany over Czechoslovakia and Holland over Greece. By that evening though, a new international phenomenon had taken centre stage, the streets of Turin playing host to a running street battle between 200 English and Italian hooligans. Though 36 people were detained, the fighting, the first of what would become a familiar sight on the continent over the next decade, made only a small column on page six of The Times. The following day, however, England fans made front-page news.

June 12: England v Belgium

Greenwood's men were overwhelming favourites to beat the unfancied Belgians, but Guy Thys' men had defeated Scotland in the qualifiers and were going into the championship on the back of seven straight victories and a 13-match unbeaten run.

The game started well for England. After 26 minutes, Ray Wilkins chipped the ball over the Belgian back four, ran through them and lobbed home over the advancing Jean Marie Pfaff to make it 1-0. But the lead lasted a matter of moments, striker Jan Ceulemens stabbing the ball home from a corner. Almost immediately, fighting broke out behind the England goal.

"The violence seemed to begin when the Italians cheered the Belgian goal," wrote Norman Fox in The Times.

Italian police fired tear gas into the crowd. "All of a sudden, for no apparent reason, my eyes started to water," says goalkeeper Ray Clemence. "A horrible feeling came over me and I couldn't see anything. Then I realised there was a problem behind me."

As yellow smoke clouded the terraces, police waded into the England fans and Greenwood appealed to UEFA officials to stop the match. "We just made our way towards the middle of the pitch," says Sansom. "I don't think any of the players were hurt, though a couple of them had sore eyes."

The game restarted five minutes later, both sides struggling to get back into their rhythm before half-time. After the break, though, England pushed hard for the win. With 15 minutes left, Tony Woodcock got in ahead of his marker to score, but unknown to him, the linesman had raised his flag before lowering it again.

The England players were back at the halfway line before they realised that West German referee Heinz Aldinger had disallowed the goal. It was to prove a key decision: England were prevented from getting off to a quick start, and Belgium took heed of the warning to hold out for a draw.

Ceulemans feels that England didn't take Belgium seriously, but concedes that they expected to be beaten. "England had a better side so we were surprised to hold them to a draw. It was then that we started to believe in our chances."

The result wasn't the main talking point, however. The hooligans were. "We are ashamed of people like this," said a furious Greenwood. "We have done everything to create the right impression here, then these bastards let you down."

UEFA hit the FA with an £8,000 fine for the crowd disturbances. "It could have been a lot more serious," said FA chairman Professor Sir Harold Thompson. "It is a lamentable disgrace that the work Ron Greenwood has done can be jeopardised by a few silly louts. They are not fans at all."

June 15: Italy v England

The Mayor of Turin, Signor Diego Novelli, threatened to cancel the match in the event of any more trouble from English fans

In the circumstances, a crucial game between England and Italy was the last thing the Italian authorities needed. The Mayor of Turin, Signor Diego Novelli, threatened to cancel the match in the event of any more trouble from English fans, and banned the sale of alcohol in the Stadio Comunale. Margaret Thatcher, in Venice attending an EEC summit, described the events as 'disgraceful'.

Meanwhile the players tried to stay focused on football. Many felt the hooligans were harming the team's chances, but Mills admits they were largely unaffected by the trouble.

"We'd grown up with it. Crowd violence was one of those unfortunate things that was around in the '70s and early-'80s."

Italy been beaten at home in a decade, and were unbeaten on the mainland since England's 3-2 victory in Rome in 1961.

Italy were having their own problems, outplayed by Spain in a goalless draw, but England faced an enormous task. The hosts hadn't been beaten at home in a decade, and were unbeaten on the mainland since England's 3-2 victory in Rome in 1961.

Greenwood made three changes for the game. Up front, David Johnson made way for Birtles, whose ability against man-to-man markers in Forest's European Cup campaigns had impressed Greenwood (the manager had brought the young striker along mainly with this game in mind).

Ray Kennedy came in for Trevor Brooking in midfield, and Peter Shilton replaced Clemence in goal, continuing Greenwood's unusual practice of alternating his keepers every game. For many, this was the most glaring example of his weakness as a manager - niceness.

"Ron should have chosen one ahead of the other," says Mills. "I think he was trying to be fair because they were both capable of being the England goalkeeper."

But, as Mills points out, when Greenwood finally settled on Shilton for the World Cup two years later, the side only conceded one goal in five games.

Boosted by Kevin Keegan's recovery from a stomach upset, Greenwood was in confident mood as kick-off approached. "Somebody has to win," he declared, clearly believing it would be England.

As over 60,000 fans squeezed themselves into the Stadio Communale, supervised by a massive police presence, fighting broke out on the terraces 90 minutes before kick-off, but was quickly quelled. The England team had other problems. Pre-match, Birtles was interviewed by Bobby Charlton for English TV. "There I was being interviewed by one of the game's greatest players, and I was wearing purple trousers and these really loud purple shoes. Quite what Bobby made of me, I don't know."

Nor was it the only fashion disaster. "We came out in our Admiral tracksuits, who were among the leading kit makers at the time," says Sansom. "Then the Italians, fantastically suntanned, appeared in these incredible ice-blue silk tracksuits and Ray-Bans - we felt like we were 1-0 down already."

Once the game got underway, however, England showed no signs of an inferiority complex as Wilkins and Kennedy set about interrupting the Italians' rhythm, and Birtles got stuck into the bruising encounter he had expected.

"[Claudio] Gentile did everything he could to stop me scoring. If anybody was wrongly named, it was him," he laughs. "He was one of the greatest defenders in the world but he had his methods. He was kicking and pinching and he certainly let me know in no uncertain terms that he was going to get the better of me."

As the game wore on, Bettega and Scirea missed chances for the Italians and England, too, came close, Kennedy's shot crashing off the bar. But Antognoni's influence in the Italian midfield was growing, and 11 minutes from time, the Fiorentina playmaker fed Graziani near the left flank.

Right-back Phil Neal went in clumsily, and was brushed aside by the Italian wide man, whose low cross was headed into the back of the net by Marco Tardelli. England almost snatched a point, but Dino Zoff brilliantly pushed out Keegan's last-gasp overhead kick.

After Belgium's 2-1 win against Spain, the best Greenwood's men could now hope for was the third-place play-off

"It was a very quiet dressing room after the game," says Birtles. "To lose to such a late goal was very flattening, and things weren't quite the same afterwards."

That evening, goals from Gerets and skipper Cools were enough for Belgium to beat Spain 2-1, making the Belgians' forthcoming clash with the hosts a decider for the final. The best Greenwood's men could now hope for was the third-place play-off.

Greenwood put on a brave face "I am only pleased we have been part of a game which has shown the best of football," but England's difficulties were far from over.

The day after the match, Italian newspaper Tuttosport reported that Keegan had accused Romanian referee Rainea of taking a bribe. "Nobody can take it out of my mind that he has accepted money," England's skipper was alleged to have said. Keegan fumed that the Italian press had misunderstood him, but the row rumbled on, disrupting preparations for the Spain match, until finally, the journalist who had written the piece admitted he had misquoted Keegan and apologised.

June 18: England v Spain

Criticised for the first time as England boss, Greenwood was reeling. "If I've failed, I've failed,"

For Greenwood, the knives were out. Though his team managed a 2-1 win over Spain in their final game, suddenly all of his methods were being questioned. The six changes he made for the match were seen as weakness.

"A manager who had produced a reliable and little-altered group for so long was suddenly breaking up under the real strain of competition," wrote Norman Fox. "He used 19 players in three games. His argument that all 22 players in the squad were equals was wrong and told of a nice guy who didn't like to hurt feelings."

Criticised for the first time as England boss, Greenwood was reeling. "If I've failed, I've failed," he said. "I'm certainly not making excuses for the team selection. We did our best, but it just wasn't good enough."

Nor did the players escape the accusatory fingers. "The media reaction upon our return was vitriolic," says Steve Coppell.

"I remember I was heavily criticised by former England players who'd played in my position. It was very hurtful."

We were handicapped by missing out on tournaments after Mexico. The Germans and the Italians had been there and done it over the years, and that was reflected in their performances.

Greenwood stayed on for the final in Rome, where Horst Hrubesch's late goal saw West Germany beat Belgium 2-1. Rumours that he would resign proved unfounded, but his honeymoon period was definitely over. The following season, the qualifiers for the 1982 World Cup would yield three defeats and five matches without a win at Wembley, the worst run in England's history.

Despite its promise, the squad had fallen foul of its woeful inexperience of international tournaments. Aside from Hughes, an unused member of Ramsey's 22 in Mexico, none of the squad had experienced a major finals. "Even though we'd had so much success at club level in Europe, our failure to make it to the 1974 and '78 World Cups, and the Euros in '72 and '76, meant we were lacking," says Clemence.

Sansom agrees. "We were handicapped by missing out on tournaments after Mexico. The Germans and the Italians had been there and done it over the years, and that was reflected in their performances."

Whilst the past three years have seen a great deal of progress in the art of building collective spirit and confidence, nevertheless the raw material with which he [Greenwood] is working remains much the same as that which he inherited," wrote Norman Fox. "In spite of all the medals the squad could muster, as a team they were not versatile enough to win even when the opposition was mediocre."

Coppell puts it rather more succinctly. "The Italy game was always going to be the big one," he says. "And we failed."

But for England, the true legacy of the 1980 European Championship was far longer-lasting: hooliganism. Despite the trouble, the FA optimistically made it clear they were keen to host the 1984 finals; UEFA gave the idea short shrift, awarding the tournament to France.

'The English Disease' overshadowed the football for more than a decade and, to this day, can cause bigger headlines than any group of players - even if they have got 19 European Cup winners' medals.

This article was originally published in the June 2004 edition of FourFourTwo. Subscibe!