The strange story of Newport County

Eastern Europe, expatriation and rebirth: Three moments that encapsulate a club, city and region

March 1981: A European quarter-final against East German giants, under the floodlights in South Wales. After the first leg, a contemporary German match report had noted favourably that one of the visiting forwards ran more than 15 kilometres. Interviewed after that match, a player from the Welsh team, understandably heady with a late equaliser - arguably the club's best result in their history - had dreamed aloud of a semi-final against the might of West Ham United.

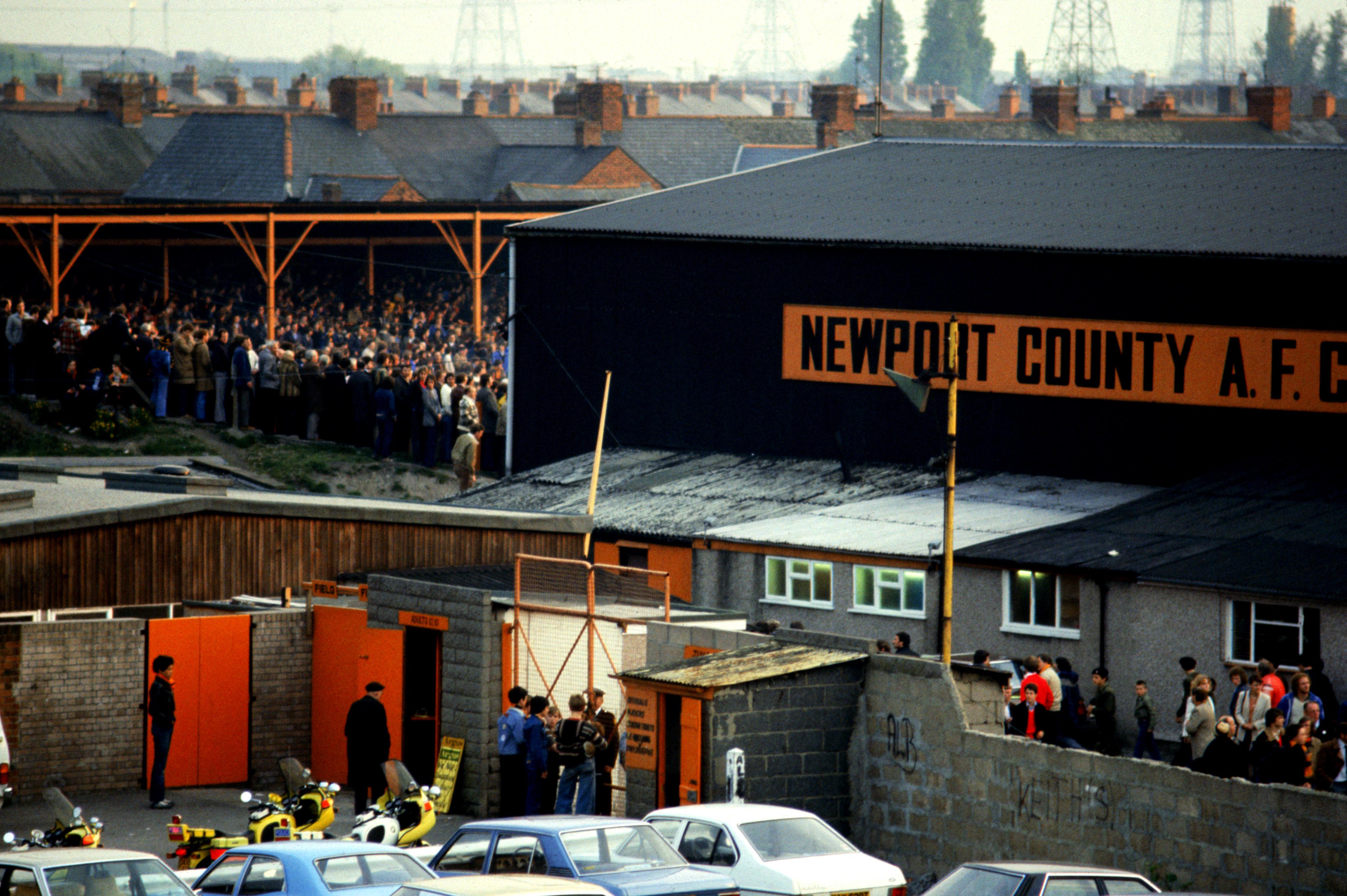

For the second leg, an unpretentiously dilapidated ground in Monmouthshire is crammed with more than 18,000 - nearly four times the average gate that season. With a dynamic vibrant squad - including a young striker who would go on to win titles with Liverpool - the future looks bright. The future looks amber.

Fast forward seven short years to April 1988. Newport are bottom of the Fourth Division, on their way to conceding more than 100 goals. Having lost three successive games 4-0 in South Wales, they travel to Torquay and put out a scratch youth team: all the first-team players have long since been sacked to save money. After they lose 6-1, the brave but demoralised youngsters have to wash the dirt off their kit themselves: there isn't even any cash for washing powder.

That weekend, a 6-0 loss at Bolton confirms Newport's second successive relegation, this time to non-league for the first time since the 1930s. Less than a year later, after failing to fulfil their fixtures with debts of £330,000 dwarfing their three-figure crowds, County finally go out of business on 27th February 1989.

***

On 2nd July 2009, wreaths were laid in Newport. Not to mark two decades since County's liquidation but to commemorate the centenary of the Newport Docks disaster, in which 39 workmen lost their lives when a retaining wall collapsed during excavations to extend capacity.

The 1909 rescuers included 12-year-old paper-boy Thomas 'Toya' Lewis. He was included because he was small and brave enough to crawl into the collapsed trench. He spent two hours with a hammer and chisel trying to free a man whose arm was trapped by a beam. Unfortunately it was to no avail. The boy survived: the man didn't. But the extension to the docks were built, are still busy, and contribute to the local economy even today. As the docks' director put it: 'The men did not die in vain. What was built was built to last.'

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

A century ago, money was raised through public subscription. In gratitude for young Lewis's efforts, he was sent on an engineering scholarship. King Edward VII even gave him a medal for his bravery, and there's still a pub in the city called The Tom Toya Lewis.

The young man's effort all those years ago is ripe with symbolism: the people of Newport, Monmouthshire do not give up. Ask the supporters of Newport County AFC.

In the summer of 1989, months after Newport County FC had been wound up amidst acrimony and absurdity, 400 proud Newportonians met at the Lysaght Institute to re-form the club. Even the building they met in encapsulated the town's defiance. Built by the firm of John Lysaght to commend the contribution of its workforce to the area's largest employer the Ord Steelworks, it opened in 1928, became a vital part of the community and even boasted a ballroom with a maple wood dancefloor. (The club's original nickname was the Ironsides, a nod to the area's strong steelmaking tradition.)

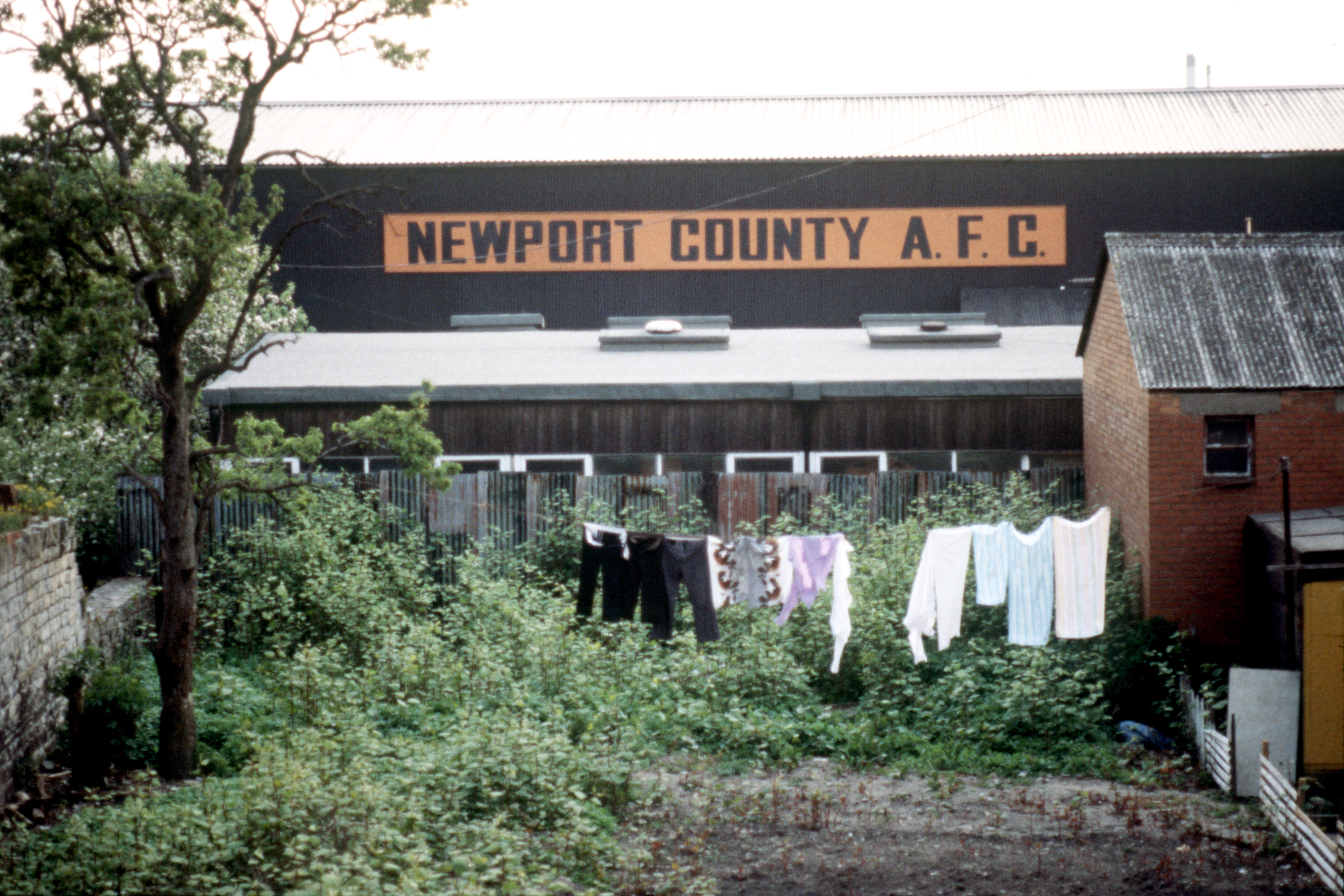

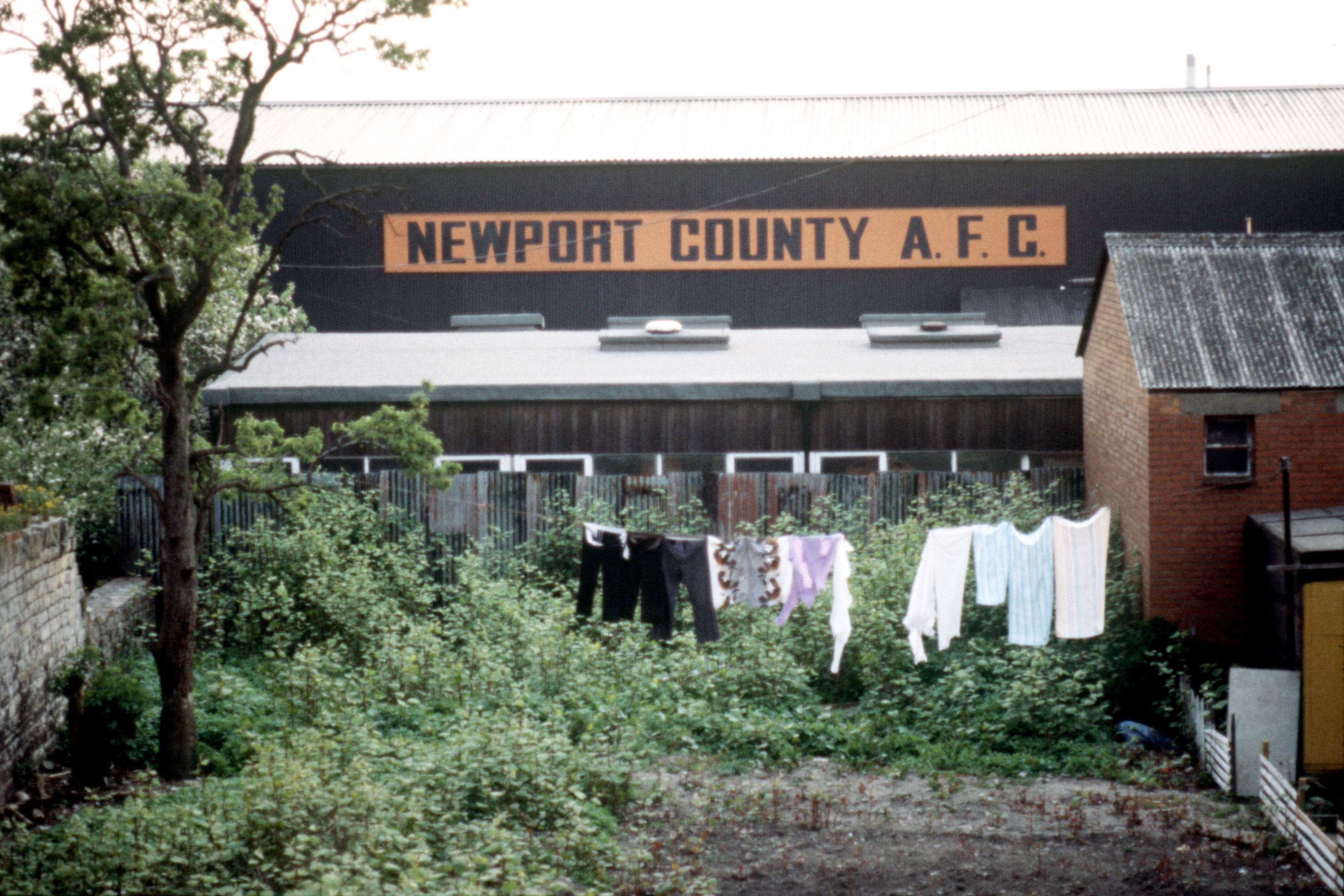

Yet by the start of the 21st century the Lysaght had fallen into disrepair. Plans were made to replace it with housing - similar to what had happened to County's historic ground at Somerton Park, which is now a residential area. Yet the locals roused themselves to prevent such an iconic building being razed: the venerable old building has had a re-fit and once again sits proudly in the city's consciousness.

There was standing room only at the Lysaght that hot June night in 1989, as the supporters of County refused to countenance their city without a football club. Their determination led to the re-formation of Newport AFC (they would become Newport County AFC in 1999) with their long-term goal of returning league football to this depressed, staunchly working-class area of South Wales. But being back among the 92 seemed a remote possibility when Newport AFC started their inaugural season in the Hellenic League, five tiers below the Football League.

Building a club from nothing was hard. Newport were compelled to play their first season in the improbable location of Cotswold market town Moreton-in-Marsh, their enforced expatriation to Gloucestershire earning them a new nickname of 'The Exiles'.

'Every game was effectively an away game,' recalled Newport president David Hando. 'Even though we had 400-plus supporters follow us up to Moreton in the beginning we needed to come back to Newport. We've fought a lot of battles to get back.'

They were forced onto the road by two considerable opponents. Newport Council, who considered the new club to have inherited the old club's debts, refused permission to play at Somerton Park until rent debts were cleared. More crucially, they were forced out of the country by the Football Association of Wales, who refused to let them operate west of the border.

'We had Newport Council telling us we were the old club in disguise and that we had to pay debts,' said Hando. 'But the FAW were saying we were a new club and we had to play on the local parks and work our way up the Welsh system. They couldn't both be right but we knew if we were to have any future at all we had to go into exile. And when we won our first promotion the FAW couldn't say we didn't exist.'

When we won our first promotion the FAW couldn't say we didn't exist"

Newport returned to Somerton Park for the 1990/91 and 1991/92 seasons, but then the craving to return to the Football League meant the club refused the FAW's invitation to join the brand new League of Wales.

'It was a worthy venture but we politely declined because our aim was the Football League,' said Hando. 'They wouldn't sanction us playing in Wales so we went into exile a second time. But when we saw they wouldn't relent we took them to court for restraint of trade.'

The club were once again ejected to England, spending two seasons groundsharing 50 miles away at Gloucester City's Meadow Park while fighting the FAW in the courts (along with fellow dissidents Colwyn Bay and Caernarfon Town) until a 1994 High Court injunction permitted their return to Wales.

In 1995, back in the city at the newly-built Newport Stadium, they romped to promotion again to the Southern League Premier Division - three tiers below the 92. Nine seasons on, a reorganisation of the non-league pyramid saw them land in the Conference South; in 2010 Dean Holdsworth's side stormed to a 103-point title triumph and promotion to the Conference National, just one tier below the Football League.

On 6th May 2013, a day short of 25 years since they last appeared in the league, Newport beat their compatriots Wrexham at Wembley to secure promotion to the Football League via the Conference play-offs. In the first ever Wembley final between two Welsh teams, Justin Edinburgh's side won 2-0 with the first goal scored by Christian Jolley, who was born five days after that last league game. After a generation in the wilderness, the Exiles had finally reached the Promised Land.

Colin Addison, who led the club over two spells in their time as a football league club talked of the impossible dream to return to the League which stemmed from that fateful meeting at the Lysaght Institute: 'People said that was our dream but we weren't dreamers. It was our mission'.

With Cardiff City having been promoted to the glamour and riches of the Premier League, Swansea City consolidating their place in it while winning the League Cup to get into Europe, and a Gareth Bale-inspired Wales again gaining critical acclaim, Welsh football is on the rise again.

But the Exiles story doesn't end there.

***

March 1981: A European quarter-final against East German giants, under the floodlights in South Wales. The old Newport County came within an ace of beating Carl Zeiss Jena in the European Cup Winners' Cup.

The German club had been founded in May 1903 by workers at the Carl Zeiss AG optics factory. They had already beaten Italian giants Roma 4-3 on aggregate in the first round, impressively overturning a 3-0 first leg defeat in Rome (which included a goal by a young lad called Carlo Ancelotti). They then beat the holders Valencia, who had beaten Arsenal on penalties in the previous season's final at the Heysel Stadium.

They had already beaten Italian giants Roma, and holders Valencia"

County had beaten Northern Ireland side Crusaders 4-0 in the opening round, the Belfast leg played amid bombings and hunger strikes, before seeing off Norwegians Haugar 6-0 on aggregate. Two strikers who played and scored in those games have gone down in County folklore: the potent Tommy Tynan complemented a young John Aldridge, who would miss the quarter-finals through injury (and later be sold for a club record £88,000 to Oxford United).

Promoted to the Third Division the previous season (while also winning the Welsh Cup), County were a settled side: only Tynan and Dave Gwyther, who had been a consistent goalscorer at Swansea, hadn't spent the majority of their careers at Newport. And now they were in the quarter-finals with Feyenoord, Benfica, Dinamo Tblisi, West Ham and Jena, who had been champions of East Germany only 11 years before and hadn't finished outside the top five since 1964.

Newport may have been forgiven for underperforming on a muddy pitch in front of a sold-out East German crowd, eight years before the Berlin Wall fell. But under wily boss Len Ashurt's leadership, they pressed as though their lives depended on it, and even a goal against the run of play failed to dampen their spirits. With a minute left the indefatigable Welsh were losing 2-1, with an away goal in the bag and a single-goal deficit to turn over at Somerton Park.

Then Gwyther skipped a tackle on the half-way line and ploughed towards the box, inviting a tired lunge before beating his man, then beating another on the by-line and playing it into the middle. A predatory Tynan, his long blond hair flowing, was waiting at the edge of the six-yard box to turn his man and slot past the keeper. There was just about time to kick off before the referee blew his whistle. County had achieved arguably the best result in their history.

Despite a valiant effort, they lost the second leg 0-1. Jena scored through East German international Lothar Kurbjuweit, then beat Benfica in the semis only to lose the final to West Ham's conquerors Dynamo Tblisi. As Ashurst said at the time: 'The boys gave it their best shot. I am so proud of them'. The tie was to live on in the hearts and minds of County fans - but also in East Germany.

In 2013, Carl Zeiss Jena celebrate their 110th anniversary. A quirky club, they now play in Germany's third tier, charging their spectators a princely €7. But they never forgot the bravery of County, nor their subsequent struggles. And as part of their 110th anniversary celebrations, they have asked the Exiles to play a friendly against them on 13th July.

As Jena president Rainer Zipfel says, 'We're very pleased about Newport County. This is quite a special game for us and for our fans. It is something very emotional.' County director of football Tim Harries agrees: 'Going to Carl Zeiss Jena will bring back so many memories.'

Newport County and their long-suffering, but unwavering fans have been through many intense lows over the last 25 years. Yet with promotion back to the Football League and a re-kindling of their friendship with the unlikely allies of Carl Zeiss Jena, they deserve to enjoy their moment in the spotlight: a reformed club built to last.

Layth Yousif is a freelance writer, followable on Twitter @laythy29

Also by Layth Yousif: Triumphs, bitter defeats and curiosities: Heynckes, Bayern and the Foals