Take note, Premier League: Serie A's radical quota changes could save Italian football

It's not just Greg Dyke looking to improve things for local youth. Serie A clubs are suffering from a lack of homegrown talent more than ever, but the introduction of new quotas and ban on third-party ownership of players could save Italian football, writes Adam Digby...

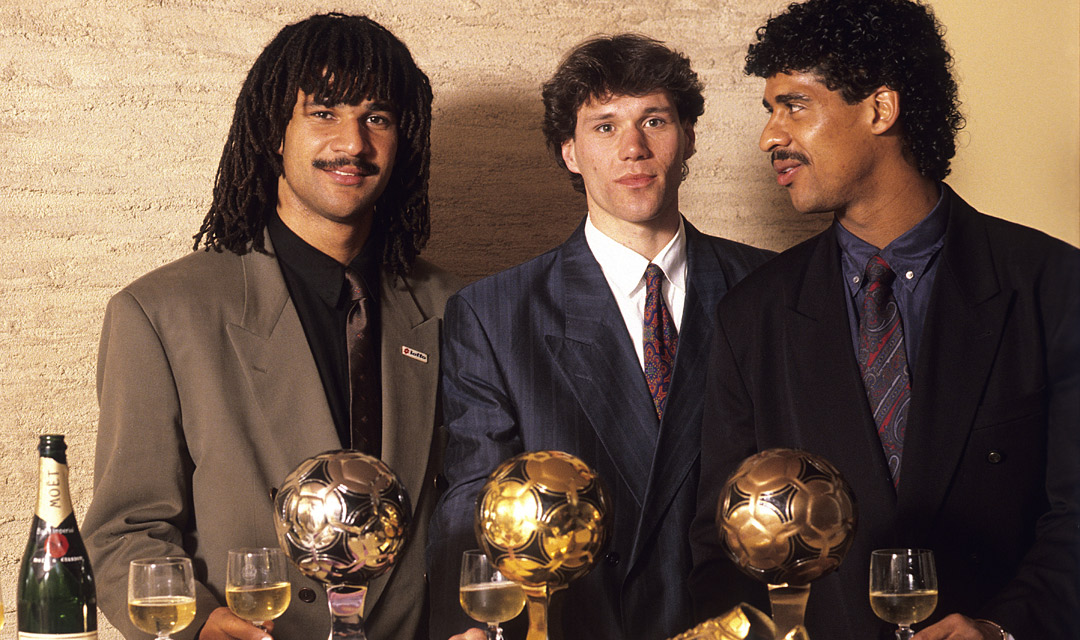

The great Milan team of the late 1980s remains one of world football’s most revered sides.

Led by the magnificent Dutch trio of Ruud Gullit, Frank Rijkaard and Marco van Basten, the Rossoneri's back-to-back European Cups were testament to their superiority.

Despite the emergence of some wonderful sides from Barcelona, Madrid and Munich in recent years, that feat remains unmatched more than two decades later.

If that fact highlights their dominance, the latest edition of the Derby della Madonnina merely reinforced the idea. In late November, Milan's current incarnation met cross-town rivals Inter – both pale in comparison to their iconic forebears. Where those brilliant Netherlands internationals were surrounded by the finest Italian talents, only three Italy-born players were in the Rossoneri line-up... still two more than Inter.

With Silvio Berlusconi no longer willing or able to compete for the most expensive players, the club is a shadow of its former self, its 38 points so far dwarfed by leaders Juventus's 67, and has never seemed further away from unearthing the next Franco Baresi or Paolo Maldini.

It's a similar story at Inter – currently two places below Milan in mid-table – and the once-great clubs reflect the wider malaise currently enveloping Italian football in general.

While it's no surprise to see an absence of Italians in the Inter team – the clue's in the club name – it reflects a rising league-wide problem. Last autumn, BBC research showed that just 45.4% of the minutes played in Serie A were from Italians, down by an incredible 19% since the 2007/08 season.

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

That figure compared unfavourably with those across Europe, with 59% of La Liga minutes claimed by Spaniards, 51.1% French players in Ligue 1, 50% Germans in the Bundesliga... and just 32.26% of Premier League playing time going to Englishmen.

Rejuvenating Italy

The lack of Italians in Italian football forced governing body FIGC to act. As Greg Dyke has recently done for the English FA, they studied the problem and upped the quota levels – but whereas Dyke's proposals for the island nation suggesting lowering the "club-trained" age bar from 21 to 18, the Italian model introduces a national restriction. In order to combat the alarming dependence on foreign imports, the FIGC decreed that from 2016, each club's 25-man squad has to include four homegrown players and four more club-trained players who were also Italian-born, putting the insular into peninsula.

With Italy’s dismal showing at the World Cup still fresh in the memory, Azzurri coach Antonio Conte has spoken publicly about the lack of young players being developed by the nation’s clubs. "You do not want to face up to certain things, that is the big problem," he said after the recent win over Albania. "Our product is dying out. We're going through a difficult generational change."

Those feelings were backed by Giorgio Chiellini, the Juventus defender discussing "a generational gap in the squad" and noting the absence of players aged between 20 and 27 in the national side.

The new regulations define ‘homegrown’ players as those who spent at least three years between the ages of 15 and 21 at an Italian club, whether in a youth sector or first-team squad, or even away on loan so long as an Italian club still holds the player's contract.

The ‘club-trained’ rule refers to a player who spent three of those formative years with the team currently holding their registration. While the first definition is commonplace – Premier League clubs are required to have eight such players in their squads – the second goes beyond those rules.

As things stood when the rules were announced, only eight teams – Atalanta, Cagliari, Empoli, Genoa, Juventus, Milan, Roma and Sampdoria – would meet those regulations.

The other 12 have work to do, with Inter possessing just one club-trained player of any kind – Joel Obi, a Nigeria international who therefore wouldn't count. Fiorentina had a startling 27 non-Italians, Udinese 26, Lazio 23 and Napoli 19.

Even Sassuolo, who had only three non-Italians in their squad, could only claim that two of the other 24 passed through their youth sector.

Under-21 boss Luigi Di Biagio lamented the lack of opportunities granted to his own squad by top-flight clubs, telling La Repubblica that the situation had improved but adding that "they still don’t play as much as they should". The former Inter midfielder went on to state that "clubs in Serie A lack courage" to grant young players space in which to grow and improve.

Third-party gatecrashing

Significantly, Italy’s long-standing and often confusing co-ownership system ends permanently this summer after FIFA outlawed the practice.

That should help clubs fall in line with the rule changes, giving them the opportunity to bring some of the talented players they have developed back into their squads rather than continually sending them around the country. Parma, later declared bankrupt, are most guilty of over-loaning: at the time of the rule change, they had no fewer than 104 contracted players out at other clubs.

SATIRE Parma forced to release 976,000 players

That Juventus and Roma lead the way is no surprise: Serie A’s top two clubs are benefiting once again from their forward-thinking management teams.

As the rules were revealed, the champions boasted the requisite four club-trained players plus a further 10 homegrown members of their squad, with the Giallorossi possessing five Italians.

The likes of Milan and Inter have little choice but to change course. If they can, Italy's biggest clubs could once again become competitive and grow just as Roma and Juventus have after their own recent struggles. With it, Serie A can slowly recapture the lustre and glamour that made it Europe's most feared league.