The extraordinary story of Arthur Wharton, the first black professional footballer

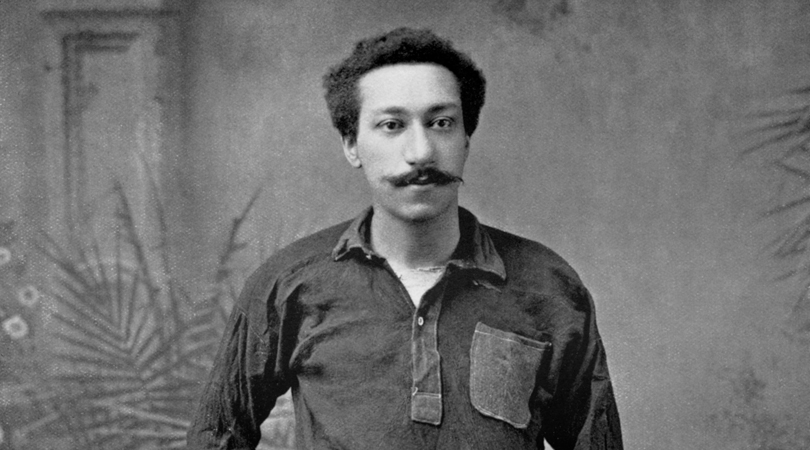

The amazing life of a goalkeeper with superhuman speed was lost for so long - but Arthur Wharton deserves recognition

Many who have walked through a particular churchless Doncaster graveyard will never have known of one its inhabitants’ extraordinary stories.

Arthur Wharton was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in 1930. He was born into conflict, as his country - then known as the Gold Coast, now Ghana - fought back against its British oppressors. Wharton was one of the lucky ones, able to flee to London, with the intention of becoming a missionary. In some ways, he never stopped running.

He flitted from one football club to the next as a young man but Wharton’s journey started at Darlington. He was a keen sportsman who’d equalled the amateur world record of 10 seconds for the 100-yard sprint, though curiously, he was most often used in goal, despite his lightning speed. He could play on the wing but would rather guard a net, showing incredible speed to close down attackers and supreme punching ability.

To equate Wharton to a modern-day equivalent is difficult. Imagine a custodian with Manuel Neuer's presence, just as fast as Theo Walcott. Now factor in that according to accounts, Wharton could jump, grab his crossbar and catch a ball between his legs. It certainly puts Rene Higuita’s scorpion kick to shame.

INTERVIEW David James: More data is needed to understand why there are so few BAME coaches

The famous Preston North End were said to be perplexed by him when they played against him. They offered him an opportunity to join their team and it was there that Wharton became part of the legendary side that managed an unbeaten league season in the 1880s, becoming the original 'Invincibles'. After that, Rotherham Town were impressed enough to give him a shot, making him the first black professional in the game.

This was an alien era of football; one where the rules that we argue about in pubs today were yet to fully crystallise. Wharton’s exploits came between stints as a professional cricket player - playing multiple sports wasn’t uncommon back then - and he even beat the record for the cycling the quickest time between Preston and Blackburn.

Imagine your club’s goalkeeper doing that. The past, they say, is another country; Wharton’s era was as foreign to us as he may have seemed to his team-mates.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Yet despite this incredible story, Arthur Wharton didn’t have so much as a headstone – let alone a footnote in the footballing history books. This was a man who played football as daringly as anyone before him or after. Opinion towards immigrants in the Victorian era was unkind, to say the very least. The mountain that Wharton had to walk up to prove his worth as a sportsman was steeper than many, if not all, of his peers.

He became the understudy to William “Fatty” Foulke, another goalkeeper-come-cricketer, who became a legendary Victorian figure. He later coached Herbert Chapman, the pioneering manager who became the father of the modern game. He was an Invincible at Preston North End. Yet for so long, history neglected to mention Arthur Wharton and his contributions to sport alongside these other men.

How many more aspiring black sportsmen and women like Wharton will we never hear of? How many were denied opportunities in the Victorian age? What else could Wharton have achieved were it not for the colour of his skin? An international cap, surely, would have been one of those things. His tale is one of struggle and strife, of brilliance and individuality but equally, it’s one of colonial rule and how minorities were treated in our country.

Arthur Wharton retired in 1902. He became a colliery haulage worker and joined the Home Guard when war was declared in 1914, pledging his life to the country he had made his home 30 years before; the country of his wife and children.

His latter years were crippled by a drinking problem and he died, penniless, at the age of 65 in Yorkshire.

In 2011, the FA invited his granddaughter, Sheila Leeson, as a guest of honour for England’s friendly against Ghana. The FA had plenty to thank Leeson for, too - Wharton’s story was kept alive from her own family photos. She helped to uncover one of the great stories of sporting history and now it’s immortalised in British footballing folklore.

Today, Wharton has his gravestone. He is also the subject of a beautiful 16-foot statue at St. George’s Park, depicting him leaping to touch a shot over a crossbar. Chronologically, he is the first footballer recognised in the English Football Hall of Fame. It’s the least that he deserves.

While you’re here, subscribe to FourFourTwo and save 48% – available until Christmas. It’s the perfect gift idea for anybody who loves football (including yourself)!

NOW READ

RICH JOLLY Are Marcelo Bielsa's Leeds Premier League innovators – or throwbacks?

ARSENE WENGER EXCLUSIVE Manchester United wanted me to take over as manager

FIFA 21 Essential tips from FIFA experts, pro players and YouTube stars

Mark White has been at on FourFourTwo since joining in January 2020, first as a staff writer before becoming content editor in 2023. An encyclopedia of football shirts and boots knowledge – both past and present – Mark has also represented FFT at both FA Cup and League Cup finals (though didn't receive a winners' medal on either occasion) and has written pieces for the mag ranging on subjects from Bobby Robson's season at Barcelona to Robinho's career. He has written cover features for the mag on Mikel Arteta and Martin Odegaard, and is assisted by his cat, Rosie, who has interned for the brand since lockdown.