Grace, pace, strength and vision: The making of Thierry Henry

Thierry Henry is not just an Arsenal legend; he is one of the Premier League's greatest ever players. FourFourTwo revisits the career of a Gooner god

This feature first appeared in the Summer 2020 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe today and pay just £9.99 per quarter

In such moments does a crowd collectively hold its breath. When spotlights inside the Bernabeu converge on Thierry Henry as he wins the ball by the centre circle, those in the stands don’t yet know what’s coming. But so few footballers in history have been so dangerous from this position.

The Arsenal captain swivels, then slides into second gear, accelerating away from Ronaldo using his deer-like stride. He slaloms between two challenges before breezing beyond Sergio Ramos’ lunge, then completes his darting act by arrowing a low shot across Iker Casillas into the bottom corner.

Henry runs to the corner flag in celebration – arms outstretched, chin raised. Arsenal lead Real Madrid 1-0 in the Champions League last 16, despite an injury crisis forcing them to field a D-list defence. And that’s how the scoreline stays – because when Thierry Henry is on your team, you always have a chance.

📅 #OnThisDay in 2006 at the Bernabéu... 🔥🔥🔥 This solo run & goal by Thierry Henry 😍#UCL @ThierryHenry pic.twitter.com/BcXSOv2NBoFebruary 21, 2019

Some players are lucky that they can run with a ball like it’s stuck to their instep, but few have been given Henry’s gifts; the precious ability to drag their team over the finish line, no matter who the opposition.

The first time Arsenal fans caught a glimpse of it was on a grey 1999 day in Southampton. Up until then, the young Frenchman was little more than a gangly, and goalless, £11 million winger haunted by Nicolas Anelka’s sour-faced ghost.

“I had to be re-taught everything about the art of striking,” he later told FourFourTwo, nudged along by mentor Arsene Wenger, who insisted he stick at it after years ‘wasted’ wide.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

But on that September afternoon at The Dell, something clicked as he spun Saints substitute Marco Almeida – making his only appearance for the club – and curled a fine effort past Paul Jones for his first Gunners goal.

It was at Southampton that @thierryhenry scored the first of his 2️⃣2️⃣8️⃣ goals for us 🌟Not a bad way to start, eh 👏 pic.twitter.com/kSetlcwP8hDecember 16, 2018

From there, habits began forming. With every strike, Henry stood a little taller; he finished his first season in English football with 17 league goals, then struck another 17 in his second. In those early days at Highbury, however, Henry was not a fully-developed star; just a swirling, nebulous force drifting in and out of matches and sometimes sprinkling them with gold dust. In a time before name-calling on Twitter and outrageous expectations, the north Londoners’ then-record buy was afforded ample patience.

Arsene knew best, after all.

Henry required time and space to find form, because he wasn’t like other strikers. The ego was deep-rooted, but he wasn’t greedy for the goal. The 22-year-old was more Road Runner than Wile E Coyote; a Clairefontaine speedster rather than Ronaldo with a sharper haircut. So many forwards of that era had the air of bland Bond villains, all boring gadgets and dreams of domination, but Henry claimed he “wasn’t born with a gift for goals” and even refused to take penalties that he’d been fouled for.

“I think it’s a shame there’s a lot of focus on the guy who puts the ball in the net,” he told FFT. It was hardly Alan Shearer DNA. So, tired of the common conjecture which made No.9s the focal point and heroes of every move – not always for the right reasons – the Frenchman became his own breed of striker. “I just wanted to be myself,” he asserted.

Henry netted 24 league goals in 2002/03, his fourth season of English football after arriving from Juventus, but the assists column reading ‘20’ was far more noteworthy – and for now, remains an astonishing Premier League record. Arsenal’s talisman could assist himself – that delightful flick and finish against Manchester United in October 2000 a perfect case in point – but he teed up goals galore for team-mates, tilting a little of the limelight in their direction like a compere on a variety show.

“Maybe I don’t have that selfishness which makes some strikers special,” he once queried. “I’ll get upset when people don’t pass to each other. To play good football is fragile.”

‘Fragile’ was a word often used in conjunction with Wenger’s Arsenal sides. They were bound by belief, that most volatile of ingredients, and everything they did had a delicate grace to it.

Henry confirmed as much, claiming, “When one player isn’t in the rhythm of the team, the team cannot exist.” But deep down, becoming a master assister was another way of showing that he could have a striker’s bullish mentality.

Henry assisted more goals simply because he refused to compromise his game.

Released by Wenger’s expression-led values, the No.14 refused to bow to the mechanics of a 4-4-2, instead bending it out of shape. Henry may not have had a selfish streak, but he did have a ruthless belief that his instinct was king. When he eventually discovered it at Highbury, opposition sides were in trouble.

The 2002/03 season was when Henry began to carry the team on his back; most famously when he surged from his own half in a North London Derby like a glowing Pac-Man, eating through Tottenham’s ranks before firing home the opener in a 3-0 Highbury success. He was becoming a complete striker.

On a wintery night in November 2002, Henry ascended to his throne, tearing Roma apart in their own colosseum with a shimmering treble. His first goal was a trademark side-footer; his second, a loose ball smashed past Francesco Antonioli. The Frenchman finished off with an effortlessly brilliant free-kick which glided over the Giallorossi wall and into the top-left corner. “When he is on fire, he is impossible to stop,” marvelled Roma boss Fabio Capello.

🗓 November 27, 2002⭐️ @ChampionsLeague😊 Roma 1-3 Arsenal🎬 @ThierryHenry stars in The Italian Job 😎 pic.twitter.com/0nax3P4UrnNovember 27, 2018

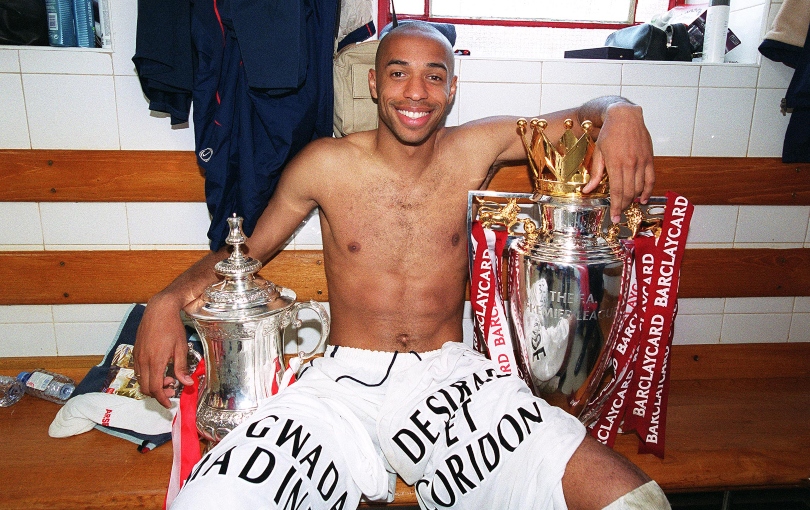

Yet even a burning Henry wasn’t enough for Arsenal, who ended that campaign with just an FA Cup for their efforts. A stellar season for some, but it stung Wenger’s men.

Henry returned in 2003/04 with a vengeance. He hit 10 league goals in Arsenal’s opening 11 league games and helped dismantle Inter at San Siro, scoring twice in the north Londoners’ remarkable 5-1 victory. The marksman looked angrier – he’d ditched the Tom Hardy grin and gone full Warrior.

Interestingly, though, Henry didn’t refine his game to become a better footballer. While so many strikers lose their teenage bombast and evolve into lethal killers in their 20s, Arsenal’s star man seemed to do the complete opposite: embracing embellishment, adding more frills and thrills. He revelled in becoming Highbury’s elected entertainer, dazzling his subjects with trickery, breathtaking speed and carnival flicks.

“Thierry’s acceleration will take him past any defender in the world,” said Dennis Bergkamp of his team-mate. With the 2003/04 title race beginning to boil, Henry handed out a lesson in exactly what the Dutchman meant.

Arsenal’s half-time break of their April clash with Liverpool was the longest 15 minutes of their unbeaten season. Losing at Highbury, the Gunners were bruised: that interlude became a reflection not just of the previous 45 minutes, but offered flashbacks of recent heartbreaks. The dust hadn’t settled from agonising defeats against Man United (FA Cup semi-finals) and Chelsea (Champions League quarters) in the past six days, and their 2002/03 title collapse still hurt. Michael Owen had slotted Liverpool 2-1 in front that Good Friday afternoon – it felt like the 2001 FA Cup Final all over again.

But less than a minute after Robert Pires had equalised, Henry did what Henry had come to do so often: pick the ball up close to halfway, take a single glance and then stride through the heart of Liverpool’s backline to put Arsenal 3-2 up. “He could take the ball in the middle of the park and score a goal that no one else in the world could,” Wenger once gushed of his prized protégé.

Henry finished the day with the matchball – an unbeaten title beckoned.

👑 Just King things... not everybody understands ✌️😎 🗓 #OnThisDay in 2004, @ThierryHenry scored a hat-trick to lead us to a 4-2 victory over Liverpool at Highbury pic.twitter.com/ckG4xitKWsApril 9, 2020

In the years that followed, the strain to pull Arsenal towards more crowns increased. The Gunners conceded their title in 2005, but won the FA Cup in a dour final against Man United, after which Wenger admitted he parked a bus; partly, because Henry was injured.

EXCLUSIVE Arsene Wenger: Manchester United wanted me to take over as manager

Patrick Vieira departed for Juventus and his compatriot took the captain’s armband. It was a natural progression from Henry’s role as the exhilarating frontman of his side, and after 30 goals in all competitions during 2004/05, the Frenchman led by example with 33 in 2005/06 – including that moment in Madrid. And so Henry’s Arsenal career came down to Paris in the spring of 2006: a clash in his home city against Barcelona for the European Cup – the one piece of silverware he had never seen his own reflection in.

At 1-0 up, the Gunners’ captain peeled away from Barça’s high line, with that familiar stride taking him close enough to see the whites of Victor Valdes’ eyes. But for once, Henry missed. Barça bagged two increasingly inevitable goals after Jens Lehmann’s early red card – and with them, the Champions League trophy. Arsenal haven’t reached a final since. “With the team that we had, we failed,” sighed Henry.

EXCLUSIVE Arsene Wenger admits "biggest regret" – never winning the Champions League with Arsenal

But he remained at Arsenal, to go again with a new four-year deal. Fittingly, after a hat-trick against Wigan to round off life at Highbury, the Frenchman scored the Gunners’ first-ever goal at the Emirates Stadium – albeit unofficially, in Bergkamp’s testimonial against Ajax. He hit a late January winner against Man United too, in the first game where the new ground rocked with the same verve that the old place used to.

🗓️A decade ago todayOur first game against @ManUtd at the Emirates...It's 1-1...It's the 90th minute...Step forward, @ThierryHenry👑 pic.twitter.com/u2u6KDN2lnJanuary 21, 2017

A month earlier, all had seemed rosy. “The club have the same ambitions as me,” he said. “Regarding the recruitment in the summer, my confidence was not betrayed. I am at Arsenal for life. I will not go to Barcelona.”

There was little doubt Henry was increasingly alone at his beloved club, however; one of few Invincibles among early 20-somethings trying to make their own way in N5. Top-two finishes had spilled into fights for a top-four place, and Wenger’s own future at the club was uncertain. Sure enough, the captain would regret his own words when he finally swapped leafy London Colney for the heat of the Camp Nou in 2007. It was time.

“The first day, I didn’t dare to look him in the face,” Lionel Messi said of his new team-mate. “I knew everything he had done in England.”

But a challenging first season in Spain awaited Henry, now 30 and having to fight for a place upfront with Messi, Samuel Eto’o, Ronaldinho, Eidur Gudjohnsen and a young Bojan.

Initially, manager Frank Rijkaard told his new signing – a top-four Ballon d’Or finisher in five of the previous seven years – that he wouldn’t get into the side.

“I went there knowing that I wasn’t going to start,” Henry later revealed. “But I thought, ‘I’ll show you that I can’.”

Although Rijkaard ended up starting Henry more than any other forward in 2007/08 after an early injury to Eto’o, the Frenchman’s debut campaign was no party-starter; 19 goals in all competitions made him Barça’s top scorer, but his tally was just one more than Eto’o’s despite making 19 more appearances. The Catalans won nothing, and Rijkaard was out.

But incoming coach Pep Guardiola had new ideas. An unused substitute when Henry took Roma to the cleaners, Barcelona’s new boss remoulded his ageing icon. “I learned how to play football again,” summarised Henry.

He rediscovered his lightning burst, studied what Guardiola asked of him and re-acquainted himself with the left wing, forming a lethal triumvirate alongside Messi and Eto’o. In December 2008 he struck a hat-trick against Valencia, but saved his most memorable display for May the following spring: a scintillating two-goal show in Barcelona’s 6-2 rout at the Bernabeu, cruelly cut short by injury after an hour.

⚡️ Lightning only strikes once. @ThierryHenry strikes twice.#OnThisDay 2009 #ElClásico pic.twitter.com/xFvJKCLif9May 2, 2020

Henry also scored against Lyon and Bayern Munich en route to another Champions League final – and this time he got to hold the famous trophy after a 2-0 win over Man United in Rome.

In 2008/09, the world acknowledged Messi as football’s new conqueror – 38 goals in one season at 23 will do that. Eto’o helped himself to 36, while Henry netted ‘only’ 26, adding 10 assists for good measure. He was back to his supporting role, and happy to do so having led the charge for so long.

Before Messi’s effortless climb to the top tier of footballing royalty, however, Henry was the most complete player that the noughties had to offer; a breathtaking mixture of grace, pace, strength and vision.

Henry smashed more goals for Arsenal than anyone else; for France, too. Kevin De Bruyne matched his Premier League assists record in 2019/20, but it’s telling that it has taken this long, while ignoring the fact Henry also scored 24 league goals in 2002/03.

But perhaps what truly set Henry apart was making it all seem so easy. He made a languid, stop-start change of pace look cool, justified a Gallic shrug with his excellence, and blazed a trail through Europe with panache. He didn’t just run with the ball – he danced with it. And he had a whole lot of fun while doing it.

While you’re here, subscribe to FourFourTwo and save 48% – available until Christmas. It’s the perfect gift idea for anybody who loves football (including yourself)!

NOW READ

COMMENT We're learning a lot from Arsene Wenger's return to the public eye – it's just not what we expected

EXCLUSIVE Arsene Wenger reveals how close he came to signing Cristiano Ronaldo at Arsenal

Mark White has been at on FourFourTwo since joining in January 2020, first as a staff writer before becoming content editor in 2023. An encyclopedia of football shirts and boots knowledge – both past and present – Mark has also represented FFT at both FA Cup and League Cup finals (though didn't receive a winners' medal on either occasion) and has written pieces for the mag ranging on subjects from Bobby Robson's season at Barcelona to Robinho's career. He has written cover features for the mag on Mikel Arteta and Martin Odegaard, and is assisted by his cat, Rosie, who has interned for the brand since lockdown.