Tony Adams' demons: "The sweats, hallucinations, terrors... the voices... this is not normal"

In a brutally frank account, Adams recalls his turmoil in the build-up to Euro 96, the horror of his suicidal bender after England’s exit – and how Paul Merson of all people helped him sober up

Illustration: Paul Lacolley

He’s missed. I don’t believe it.

What a bloody... wait, I’m captain of England – I can’t get too angry with Gareth. I can’t show him how much this hurts. He’s going to be in bits. I need to protect him and rally all the players – think of the team and not myself.

I can remember seeing Gareth walking from the halfway line towards the penalty box. He had seemed really confident. I’d been standing next to the coach, Terry Venables, when he’d come over to us. I was due to take the first sudden-death pen, but there’s Gareth looking at us both and saying, ‘I’ll have the next one’. Super confident. Tel looks at me and we both nod. Go on then, son.

But he’s missed. I don’t even watch as Andreas Möller steps up and wins it for Germany. My arms are around Gareth – I have to help him. If I look after everyone else, my own agony isn’t real. Nobody is going to have a go at Gareth. I’ve got his back.

We take the lap of honour. No, it’s a lap of sadness, really. Here we are on this beautiful, balmy summer’s night in London. We should be celebrating England’s first major final in 30 years but instead, despair. Not me, though. I have to look after everyone. I push Gareth around the pitch. Literally push him around.

I clap the crowd and then head back inside the dressing room. Shin pads and towels hit the floor and there’s the sound of running showers. Team-mates sit, heads in hands. Those who didn’t play try to console, try to find the words, but there are just none. I try to rally the troops. I stand up and make a captain’s speech.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

"Lads, get those heads up," I say. "We have been absolutely brilliant and done this country proud. Each and every one of us should hold our heads up high… except you Gareth." I turn to Gareth Southgate. "Gareth, you f**king idiot. You’ve cost us the European Championship." The room explodes with laughter. I look over to my right and there it is. The fridge with all the drink. That’s what I want. I pull the ring from the can and lager slips down my throat. It’s only Carling, but it tastes like Dom Perignon.

That was my first drink in weeks and it’s bliss. It had been a difficult build-up to Euro 96 – from the January I'd been in the shit. Turmoil. My wife had left me and taken the kids, I was injured after having an operation on my knee and not playing for Arsenal. I was in a bad place where I don’t want to drink, but I’m still getting drunk.

I was worried about even making the England squad but Terry was great, keeping in touch, telling me that I was his main man. One day we meet up in the West End at Scott’s, a lovely fish restaurant. "Fancy a drink, Tone?" he asks. "Yes please, Tel."

We have a couple of bottles of nice wine and Terry leaves. It’s 4pm. I’m in town, make some phone calls and am on a bender. Disappear for a bit. The club can’t find me, but that was the norm – dark places. I’m basically in the shit.

But come April, I’m literally ticking off all the days on my bedroom calendar until the tournament starts. What I could do is use football as a way out. So I get to work. Train like a madman. On the treadmill, running around the pitch, tunnel vision. It’s the only way I know and I’m getting fit, ready to play. Terry made me the team captain, which wasn’t easy as David Platt was pissed off. I would have been. But I’m captain now.

What I could do is use football as a way out. So I get to work. Train like a madman

Then we go to Hong Kong for a pre-tournament tour and that's tough. I’d been out there in 1995 with Arsenal for a debauched trip – sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll.

I knew how crazy this place was and I’m struggling as the lads have been given a night off and they want me – the captain, big Tony – out with them as well. "Come on, skipper," says a young Robbie Fowler. "We’re all going out." I know where they’re going but I just can’t. I’m terrified but still give it the big responsible captain act. "Not for me, lads. I’ll get drunk with you after we win it."

I must have looked like the most focused man around. The perfect role model. But inside I’m in bits. I get in the lift and go up to my room on the 14th floor. I lock the door behind me and then go out onto my balcony.

I look out over the city. I know what's going on behind all of those flickering lights. I want to be out there, I want to be with them. I can’t wait for morning. That’s such a long night – ‘white-knuckling’ as we call it in AA.

I would always be first to the bus for training, knocking on players’ doors to wake them up – an hour early. Driven. Addicts can be really driven and that’s what I was that summer. But now we’ve lost in the semi-finals against Germany, we’re out and we’re back at the hotel. There are options. We can go home that night but no one wants to.

The team sit around the bar, drinking beers, talking about what had happened. I sit down with Don Howe and Terry, and we drink and talk. Slowly people go to bed, but not me – 3am, 4am, I’m up and drinking. I’m an alkie so that’s normal. Nothing out of order, but I drink to pass out. Eventually it’s what I do. In the morning, people are leaving. Team-mates pat each other on the back, say their goodbyes and drive into the summer sunshine. Off to see their families, off on holidays with their wives or girlfriends.

I sit in my room and it feels barren. I’ve got a packed suitcase but I don’t have anywhere to go. I’ll call some mates. Where’s the nearest pub? That’s it. A pub garden. It’s a beautiful day. I go to the pub, and that’s the start of a six-week bender. Benders like that are hard to explain: I’m lost, bewildered, confused.

You know what? There's no use in over-analysing it – I’m just getting smashed the whole time, day after day. Some of it's fun, and I’m sure I think I’m having the time of my life. The whole country wants to buy me a drink, shake my hand and have a word. I’m captain of the best England side in a generation. "Everyone’s talking about you at school," my 12-year-old says. "Everyone loves you."

I don’t feel any love. I don’t feel nothing. Everything was suppressed. Leading up to the tournament I'd suppressed all my feelings with football. That had finished, so now everything is about the booze and it becomes a blur. Out in a pub garden or at a club, sometimes eating, often not. Personal hygiene? That goes out the window. Wake up and stand in a shower. Sometimes just splash some water in my face. Get back out and start again.

NEXT: " I ended up out on Grafton Street and in an argument with three Chinese guys"There were odd times when I tried to look after my responsibilities. Since the January I'd wanted to woo my wife back. I’d bought her a flat in Fulham and rented us a flat in Hampstead, thinking that was cool. I had five houses, two boats, three cars, no driving licence and my head firmly up my arse.

One day, I took the kids down to Cornwall. A five-hour drive, settled them into the house, put them to bed, got pissed and passed out, was woken up by the kids, couldn’t handle it and so got in the car and drove them home. Madness.

I needed another op that summer. I sat in the private hospital bed, ordered two bottles of Chablis, had a shot in my arse and was away – cracking jokes and chatting up all the nurses. But what goes up must come down, and rather than getting fit for the new season I’m in pubs in Bethnal Green more than I’m at training.

Niall Quinn got married that summer and I flew over to Dublin. I can’t remember much about it, but I did end up out on Grafton Street and in an argument with three Chinese guys. I must have said something because they want to fight me. I pick up an empty bottle off the floor and smash it on my head. They’re thinking, ‘If he does that to himself, what might he do to us?’ and they walk off.

I can talk about these stories now and laugh as I survived, but I was getting into serious situations. I’d leave strip clubs with numerous girls, paying for sex and hating every minute of it. I’d wake up having pissed myself or worse. The thing is, if you'd knocked on my door on one of those days and said: ‘Come on, Tone, look at you, you’ve shit yourself, you’re a mess,’ I’d have laughed it off.

Then there was Arsenal. Bruce Rioch was our boss and, to be fair, he had a big job on his hands. He's joked since that he felt like an agony aunt as so many of his squad had issues, and I’ve apologised to him as I let him down. On so many occasions, he and the club couldn’t find me. We had a terrible pre-season and Bruce was fired.

So what? I might have shown some remorse, and now of course I’m sorry, but at that time it was back to the pub. I hated my life, so why not do things that are fun, or what I thought was fun? Now I can see that I was out of control. Loads of people go out and get drunk. They even have benders, but then they stop or they grow out of it. I crossed a line and couldn’t come back.

Suddenly, I wanted to give it up, but I couldn’t. I’m Tony Adams, centre-half and England captain. I thought I could beat anything, but now it had dawned on me I couldn’t. I’m stuck here and that is f**king terrifying.

It’s the Four Horsemen-of-the-Apocalypse terrifying. Bewilderment, terror, confusion. I thought of ending it. I certainly didn’t want to live, but I was scared of killing myself. The pain was all too much but I just couldn’t bring myself to do it. No man’s land. I had hot sweats, I had panic attacks, I thought I had AIDS because of some of the people I’d been with. I’m lying in bed thinking there is someone coming out of the cupboards. The phone’s ringing and I can’t answer it. There are voices inside my head saying things. Proper gone. This is not normal.

Suddenly, I wanted to give it up, but I couldn’t. I’m Tony Adams, centre-half and England captain

My dad called by and I’m a mess. ‘You’re a drunk, son,’ he says to me. I can hear his words and I feel ashamed, but I still go to the pub anyway. I get smashed and the self-loathing quickly returns. Then on Friday, August 16 at 5pm I head off home, buy myself some fish and chips and get into bed with them. I pass out and go through hell over that weekend.

The sweats, the hallucinations, the terrors – I can’t do this any more. I wake up on Monday morning, those fish and chips still next to me, and get ready for training. I order a cab, reach the car park and there’s Paul Merson. Say something. "Merse," I whisper to him. "I’ve got a bit of a drink problem." "Join the club," he replies, and recommends an AA meeting nearby in St Albans.

I did a bit of digging and discovered there was a meeting in Fulham close to my flat, so later that day I stood outside this building, staring and wondering. It was a warm summer’s evening – the sort of night that would normally draw me to the beer garden, but here I am. Shall I? Shan’t I? I’ve got no one, nowhere. I start to move and walk inside. I had surrendered.

I walked in and from there I found a way not to drink. I loved the meetings. Something there connected with me and I found a way. I was injured, so I kept going to meeting after meeting. Soon I’m able to start training and I’m getting fit. Going to meetings, training, getting strong, more meetings.

I hadn’t planned or thought about going public with my alcoholism, but a few weeks later, one day after training, I was walking in the car park and a reporter approached me. "Are you an alcoholic, Tony?" he asks. They’d found out I was at AA meetings, and the pack’s arrived. I get in my car and they’re shouting. "Twenty grand! Fifty grand! One hundred thousand for the exclusive." Piss off.

It was never going to be about money, but right there I felt strong enough to stop and say, ‘Yes I am an alcoholic, and yes, I’m attending AA meetings. Not only that, it’s the best thing I’ve ever done.’ It felt good. It felt good to be able to admit that I had this illness.

For far too long I’d thought it was a weakness, but now, having got into AA and made friends there, I had the tools to cope. For so long I'd been the standing joke at Arsenal. All the benders, followed by me saying, ‘I’ve got this, I’m stopping now,’ and then two weeks later I’m back on it again.

Now, though, I’d found a way. And so that day when the reporters stopped me, I felt good enough to tell everyone what the problem was in the knowledge I wasn’t going to fall off the wagon in front of the whole nation.

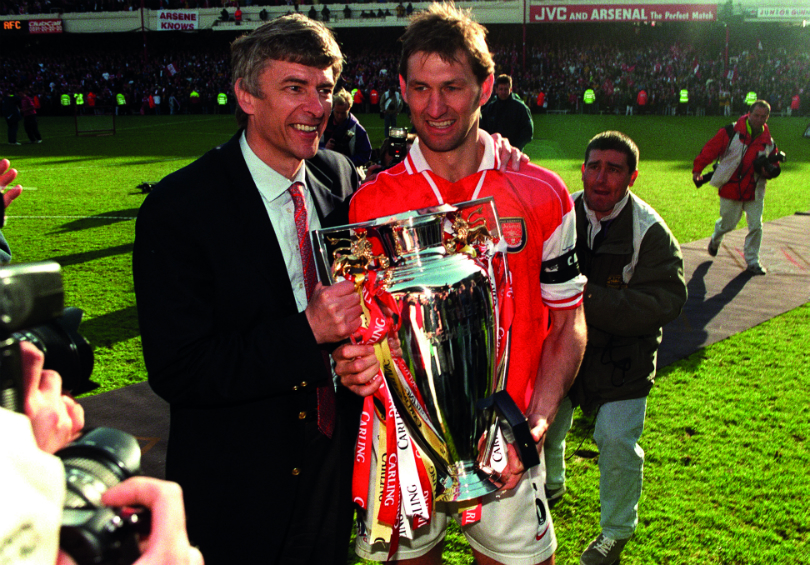

And then Arsenal appointed a new manager called Arsene Wenger. It was the perfect timing. We all felt a bit scared at first, this strange French bloke in glasses, but it was great timing. As a squad, we were ready for major change. Players who had issues were working through them, so this new guy with his new methods that were going to help us immediately got everyone’s attention, and on we went. I wonder what might have happened if Arsene had got the job when Rioch did, as not many of us were ready to listen then.

Looking back today, 1996 was such a traumatic, life-changing year for me. I went through a lot and became a totally different person. In there of course is the European Championship, and I am so proud of captaining such a fluid and tactically flexible side. Despite everything, I played really well that summer.

I watched our brilliant win over the Netherlands the other day and I actually wasn’t very good – Dennis Bergkamp could have had a hat-trick, but overall I did all right. I was kind of jealous when Matthias Sammer was named as the player of the tournament. He was great, but it could have been me! I’m proud of how I played, but two months later I was such a different person.

My treatment had seen to that. As Merse always says, you can’t stop diarrhoea with willpower. It needs medical help, and that's how we see our addictions. I'd got that help and taken it on board, though I still need to make the right decisions each day.

But from there I could enjoy my football, not because it was blocking out all the other crap, but because it was simply the sport I loved the most and the thing I did best.

My next six years at Arsenal and with England were brilliant. I loved them, as I was free then. Free as a bird.

Tony Adams’ second autobiography ‘Sober’ is available to buy now

This feature originally appeared in the December 2017 issue of FourFourTwo.Subscribe!

New features you'd love on FourFourTwo.com