Uncivil war: Why Partizan Belgrade vs Red Star is more than a game

Partizan Belgrade fans start wars. Red Star supporters are the type to give it some. For the March 2003 issue of FourFourTwo, Jonathan Wilson reported from the derby that changed the world...

The first fights break out about an hour before kick-off. Away to the right, Partizan fans swarm up the seated end to hurl abuse and coins at the Red Star fans being herded through the street below. Gradually, the Partizan fans drift back to their seats, but as another pocket of Red Star fans passes, there is another charge to the top of the ramparts.

Nobody seems too concerned. People fight at derbies. That’s just what happens. There are thousands of police in riot gear in and around the ground, but they have a thankless task. Belgrade is made for football violence. Red Star’s ground, the Marakana, is only 400 yards from Partizan’s. Between them lies a park, amply supplied with small hills and clumps of trees providing cover for warring gangs.

The game kicks off at 5pm, but Red Star fans begin to gather at the Marakana from around noon. FourFourTwo has lunch with two Yugoslav journalists, sisters Milena and Ljiljana Ruzic, in a small restaurant opposite the Marakana. Nearby is a patisserie once owned by the Serbian warlord Zeljko Raznjatovic – better known as Arkan – himself a passionate Red Star fan.

When Red Star played Hearts in the Cup Winners’ Cup in 1996, Yugoslav fans going to Edinburgh received dire warnings to be on their best behaviour because Arkan, already accused of war crimes, was in their midst, travelling on a fake passport. As a result, Scottish police, primed for running battles against one of the most notorious hooligan groups in Europe, instead found Red Star among the most docile sets of fans they had ever encountered.

"To die for Red Star would be an honour"

The restaurant is packed with Red Star fans, but the mood is far from raucous. Groups are shepherded to tables not by the maitre d’, but by a tall thirtysomething in jeans and a leather jacket. Occasionally, with great politeness, he asks diners to move tables or shuffle up to make room for another guest. “He is one of the leaders of the Delije,” Milena says.

Partizan's ultras, the Grobari (‘Gravediggers’), were officially closed down after they fired a rocket into the Red Star end at a derby, killing an eight-year-old boy. It seems the rocket was smuggled into the ground by a Partizan official

The Delije (‘Strong Boys’) are the hardcore of the Red Star fans, their Ultras. Partizan used to have their equivalent, the Grobari (‘Gravediggers’, so called because of the church and cemetery that back onto the Partizan Stadium), but the group was – officially at least – closed down five years ago after they fired a rocket into the Red Star end at a derby, killing an eight-year-old boy.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

The Delije still leave the boy’s seat empty when they visit Partizan. To make matters worse, it seems likely that the rocket was smuggled into the ground by a Partizan official. These days everybody is searched fastidiously. Approaching the ground is like boarding a plane – every few yards there is another security check, another metal detector. Even a packet of Lemsip capsules is confiscated.

Every now and again an older fan enters the restaurant. Invariably he is treated with great respect as he is helped to his table. The whole thing is reminiscent of the meeting of a large Mafia family, courtesy and food masking the violence that binds the group together.

My heart is weak: my doctors have told me I can't go to games, because I get very excited. I will be in the stand if it kills me. To die for Red Star would be an honour

The day before, FourFourTwo had met met one of these grand old men of the Delije, Mile Shnuta, now a doorman at the Marakana. He is in his sixties, his face yellow and apparently in the process of being sucked into itself. “I was one of the chant-leaders, ” his voice now scarcely more than a croak.

“Everywhere Red Star went, I went too. But now my heart is too weak, so my doctors have told me I cannot go to games, because I get very excited.” I ask if he will watch the derby on television. “No,” he smiles. “I will be in the stand if it kills me. To die for Red Star would be an honour.”

When talking to Red Star fans, death crops up a lot. The scars of the NATO bombing are still obvious in Belgrade, and the memory of the conflicts in Kosovo and Bosnia still fresh; in a country so haunted by death, you might expect life to be accorded a little more respect than to be wished away on something as ephemeral as football.

Football happens to be its raison d’etre, but the Delije, anarchic and violently nationalistic as it assuredly is, is also a community. It was the Delije that got Mile Shnuta his job as a doorman. Milena and Ljiljana both have tales of how the Delije have spirited them away from trouble. The Delije look after their own.

Political football

Historically, that makes sense. Red Star was founded at the end of World War II by the Communists, ostensibly as the team of Belgrade University. This swiftly became the team of the people, for which read "poor". The club itself was so impoverished that it might never have got off the ground had FK Obilic and FK Slavija not donated footballs that they’d carefully protected through the war.

Red Star have always been the team of Serb nationalism, while Partizan were federalist, in favour of a unified Yugoslavia

Nevertheless, Red Star rapidly established themselves as one of the two dominant forces in Yugoslav football. The other was Partizan, the army club, named after Tito’s guerrilla forces who had liberated Yugoslavia from German occupation.

Tito, who ruled Yugoslavia until his death in 1980, was a Croat, and the army – and hence Partizan – were always staunchly federalist, in favour of a unified Yugoslavia in the form of the federation of Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Macedonia, Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina, Macedonia, Serbia and Montenegro.

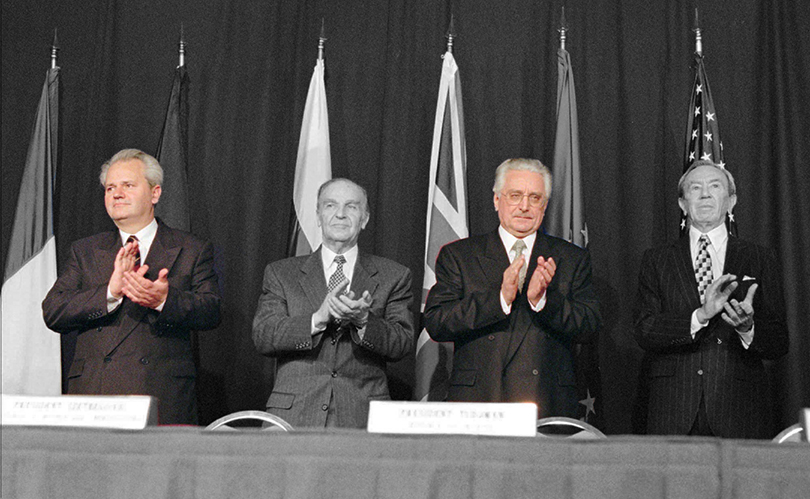

Although you’ll struggle to find reference to it today, Partizan’s president in the late '50s was Franjo Tudjman, who in 1959 changed the team’s colours from red-and-blue to black-and-white, and in 1991, leading the opposition to Serbia, became the first president of an independent Croatia.

Red Star have always been the team of Serb nationalism which, manipulated by Slobodan Milosevic, tried to seize control of the smaller, weaker Yugoslav republics with catastrophic consequences.

Three days before the derby, Yugoslavia play Finland at the Marakana. As they would in a derby, Red Star fans occupy the North Stand, Partizan fans the South. Most are in club colours; there is little Yugoslav blue to be seen. After Yugoslavia’s 1-1 draw against Italy in Naples the previous Saturday, you might expect the mood to be upbeat, yet the Yugoslav national anthem is drowned out by boos and whistles.

They hate Yugoslavia. They think it should be Serbia

“They hate Yugoslavia,” says Milena. “They think it should be Serbia.” As the game kicks off, the chant starts up, “Serbia, not Yugoslavia.” It is followed by traditional Serb songs. The nationalists may soon have their wish, although probably not in the way they want.

Yugoslavia, which once included Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Macedonia, now consists of just Serbia and Montenegro. The Montenegrin president Milo Djukanovic has already promised a referendum on independence, which could come as early as 2004.

Such is the political background, but there is also the footballing rivalry. Mateja Kezman now plays for PSV Eindhoven, but he joined them in 2000 from Partizan. He played in five Belgrade derbies, and scored in each; Red Star fans despise him. Early on, an attempted kick goes horribly wrong, and the Delzje respond with hoots of derision.

Every time he gets the ball after that, he is whistled. Even when Yugoslavia take the lead through ex-Red Star hero Darko Kovacevic, celebrations are muted in the South Stand. Kezman, prolific at club level, has never hit top form for Yugoslavia, and it’s not hard to see why. “It is never easy to play in Belgrade,” he says diplomatically. “The fans can get very excited.”

The Delije take themselves seriously – but then, in the past 12 years they have brought down a government and kick-started the bloodiest European conflict since World War Two

At times it is almost comical how seriously the Delije take themselves. But then, in the past 12 years they have brought down a government and kick-started the bloodiest European conflict since World War Two. There had been Serb-Croat clashes at stadia throughout the 1980s as ethnic tensions rose, but many consider a Dinamo Zagreb vs Red Star game in 1991 to have been the real start of the Balkan conflict.

According to Croats, the largely Serb police stood by and watched as the Delije piled into the Dinamo end. Zvonimir Boban, then a Dinamo player, tried to intervene, only to be attacked himself by police.

Exactly what happened is muddied by exaggerations and propaganda on both sides, but what certainly is true is that Arkan was arrested during the fighting – suggesting that the police were not as passive as Croats claim. A few weeks later, Red Star, who had won the European Cup with a magnificent side that included Dejan Savicevic, Nliodrag Belodedici and Robert Prosinecki, beat Colo Colo of Chile in Tokyo to take the World Club Championship.

Arkan was guest of honour at the celebratory party at the Marakana, which quickly turned into a Serb nationalist rally. After the team had paraded their trophy, Arkan held up his spoils – a street sign stolen from a Croatian village. Soon he, and the ‘Tigers’, his paramilitary group, many of them apparently members of the Delije, would be back for more.

NEXT: Turning against Milosevic

Turning against Milosevic

At that stage the Delije were pro-Milosevic, keen to push the borders of greater Serbia as far into Bosnia as they could. But by 2000, after the NATO bombing, the mood had changed. If the Delije are to be believed, Milosevic was undone by a crowd disturbance at a Champions League second qualifying round first leg match between Red Star and Torpedo Kutaisi.

As Red Star romped to a 4-0 win, the Delije chanted, 'Do Serbia a favour, Slobodan, and kill yourself'

“I was there,” Ljiljana tells me. “What happened was unbelievable. You have to understand that before that day, even if we didn’t like Milosevic, we wouldn’t dare say that.” But, as Red Star romped to a 4-0 win over the Georgian champions on July 26, the Delije chanted, “Do Serbia a favour, Slobodan, and kill yourself” a particularly barbed taunt given the history of suicide in Milosevic’s family. The police weighed in, but the Delije fought back.

A Red Star banner was seized, and two policemen began symbolically trampling it into the ground. The then Red Star coach, Slavoljub Muslin, persuaded them to hand it over, and threw the flag back to the crowd. The gesture was huge. Muslin supported them, Red Star supported them. Suddenly anything was possible.

Dissent spread to other stadia. Virtually every game became an anti-Milosevic rally. On September 24 2000, Milosevic suffered a humiliating election defeat to Vojislav Kostunica. He tried desperately to cling to power, first demanding a second round of voting, and then securing through the courts an annulment of the election. This time, though, the will of the people was not to be thwarted.

There was a general strike. Pockets of dissent began to spring up across Serbia. In Cacak, 60 miles south of Belgrade, Mayor Velja Ilic, a hardline opponent of Milosevic, gathered opponents of the regime and marched on the capital. By the time his column, a bulldozer at its head, reached Belgrade, it was 10,000 strong.

Once there, Iljic’s forces were joined by the student opposition group, Optor, and by the Delije. They smashed down the doors of the state television station, and set the building on fire. “We were sick of watching state television,” said Iljic.

“We got fed up with living in Milosevic’s Serbia. I planned it all with my mates. It was Cacak’s humble contribution. We got sick of the way the opposition was going. It was useless. We’d march, criticise Milosevic and then everybody went home and he was still there. We decided, ‘We are men, let’s do it’.”

The police line broken, the protesters surged into the building, ransacking it as they looked for evidence that Milosevic had attempted to rig the elections. It didn’t take long to find

So the crowd moved on to the parliament, which by then had been ringed by police. They employed tear gas, but the Delije, used to clashing with police, refused to be dispersed. Alexander Bozic is a Red Star fan who was at the forefront of the protestors.

“I grabbed the shield of the cop in front of me and for a few seconds we were tearing it back and forth,” he recalls. “I looked him in the eye, and suddenly he let go.”

The police line broken, the protesters surged into the building, ransacking it as they looked for evidence that Milosevic had attempted to rig the elections. It didn’t take long to find, and soon the air outside was filled with ballot papers, each marked with a cross next to Milosevic’s name.

Studio B, once an independent channel that had been turned into a propaganda outlet for the government, went off air, only to return a little later as its old self, referring to Kostunica as the elected president. Shortly after, Kostunica appeared before the parliament, and began his address to the rebels with the words: “Good evening, liberated Serbia.”

Any thought that all Yugoslavia’s problems were gone with Milosevic, though, was put into perspective a week later as Red Star faced Partizan at the Marakana. Partizan’s then-chairman was Mirko Marjanovic, Serbia’s president and a close ally of Milosevic. The once-federalist club had been taken over by a rabid opportunist sailing under the nationalist flag of convenience, a reverse as unexpected yet as characteristically Balkan as Red Star fans turning on the self-styled great Serb, Milosevic.

Even though several Partizan fans were prominent in the storming of the parliament, the way certain Red Star fans saw it they were facing the same enemy they had overthrown a week earlier. The banners in the North Stand made their feelings clear. ‘Mirko to jail; Partizan to the Second Division,’ said one; ‘The sun of freedom rises on our victory,’ read another.

The Red Star supporters were after us, and the Red Star players helped us to escape with only minor injuries. The physical damage was insignificant, but we suffered psychologically

Before kick-off, chants went up from the Partizan end calling for the resignation of Marjanovic and his cronies. Gradually the protests became more violent, and chairs and fireworks were thrown at police, who in some way represented the old guard and who had, after all, for several months brutally suppressed dissent.

Three minutes into the game, Red Star fans, angered by the trashing of their stadium, charged. As hundreds of fans poured onto the pitch, even the players became involved in scuffles.

“The Red Star supporters were after us, and the Red Star players helped us to escape with only minor injuries,” Partizan skipper Sasa Ilic recalls. “The physical damage was insignificant, but we suffered psychologically.”

Journalist Dejan Nikolic was in the North Stand that day. “The surge was immense and there was no point trying to fight against it,” he says. “You had a choice: either run with the crowd or be trampled on by several hundred fans. All around people were losing their balance and disappearing under the stampeding crowd.

"One fan said to me: 'They were never in the front line during any of the demonstrations. They never fought with the police, at least not while wearing the Partizan colours. Now here they are, claiming all the credit we’ll not let them do that.'” The logic is weird: Red Star fans turned up to Revolution in their red-and-white scarves; Partizan fans didn’t, so they can’t take the credit. Somewhere the line between football and war has become very blurred indeed.

NEXT: Partizan or Red Star? A country divided

Partizan or Red Star?

The day before the game FourFourTwo asks Petja, one of the Delije’s chant-leaders, why he supports Red Star. “Because of the culture,” he says. “Red Star fans are normal people, students or people who go to work. Partizan fans are cattle or geese. For us the derby is huge. It is like Lazio against Roma: it’s important for all of Serbia, for all of us.”

The players are just like the fans: without exception, every player I speak to insists he has been a lifelong fan of the club for whom he now plays – indeed, only seven players have ever played for both clubs. It helps, of course, that every player is a Yugoslav, but even those who were born far from Belgrade supported one or the other.

Dusan Savic is sports director of Red Star, and one of their greatest ever forwards. He, like the legendary Dragan Dzajic, was born and raised in Ub, around 50 miles from Belgrade. “I have always been a Red Star fan,” he says.

“I knew Dzajic’s brother, and he got me a job as a ball boy for the derby in 1971. We got the bus in together from Ub on the day of the game. Dzajic and Zoran Filipovic, who is now our coach, were playing and we won 1-0. Three years later, I played in my first derby, and again we won, this time 3-1.”

From the youngest age you choose Red Star or Partizan even if you are not from Belgrade

His passion is replicated in the modern players. Red Star forwards Mihjalo Pjanovic and Branko Boskovic insist they would rather not play football at all than play for Partizan.

“From the youngest age you choose Red Star or Partizan even if you are not from Belgrade,” says Pjanovic, who is from Prijepolje. “I remember coming to the European Cup semi-final against Bayern Munich in 1991. We stayed with relatives in Belgrade, so I first came to a game when I was very young.”

Boskovic is from even further away. “Red Star is like Manchester United,” he says. “You choose at a very early age to support them. I lived in Montenegro so it was too far to come to games when I was younger, but I was a Red Star fan.”

And the feeling isn’t any weaker at Partizan, as their captain, Sasa Ilic, makes clear. “I have always been a Partizan fan, and I always will be,” he says. “I could move to any other Yugoslav club, but not Red Star.

There is a TV station that has its offices in the Red Star stadium, and I would never go to their studios – I will only speak to them if they come to Partizan

"There is a TV station that has its offices in the Red Star stadium, and I would never go to their studios – I will only speak to them if they come to Partizan.” Partizan coach Ljubisa Tumbakovic hates Red Star so much that he once hurled a cup of coffee across a restaurant because it was served with a red spoon.

Rather less emphatic, for obvious reasons, is national coach Dejan Savicevic, who joined Red Star from Buducnost Titograd (now Podgorica), before moving on to AC Milan.

“I am a Montenegrin,” he explains, “and my first club was Buducnost, so I supported them. But I always had a feeling for Red Star.” Logically, of course, a Montenegrin like Savicevic or Boskovic should support the federalist Partizan rather than the nationalist Red Star, but nothing, it seems, is that straightforward.

Fighting between each other and themselves

Police maintain their positions ringing each end, and do not intervene. The reasoning seems to be that those who go in the ends surrender themselves to the ends

All that is certain is that at the derby the Delije and the Grobdari will fight, if not with each other, then among themselves. Police maintain their positions ringing each end, and do not intervene. The reasoning seems to be that those who go in the ends surrender themselves to the ends.

Serious trouble broke out at this season’s UEFA Cup tie between Red Star and Chievo when police broke the unwritten rule and entered the North Stand at the Marakana. Below the press box, in the main stand, though, red-and-white sits happily next to black-and-white, while the stand straight opposite is all but empty – tickets are overpriced at 800 dinars (£8.50), says journalist Milena.

The violence, it seems, is very much confined to those who want it, with both sets of fans having their choreographed routines before kick-off, Red Star holding up large red sheets of paper, and Partizan waving what appeared to be giant bin-liners.

As the game kicks off, the heavens open, sparing the local firemen their job of hosing down the running track to protect it from scorching as both sets of fans hurl flares towards the pitch.

Within three minutes, the Red Star flares are out again, as Boskovic kicks a long ball over a leaden-footed Branko Savic, runs on and slips the ball calmly past Radisa Ilic. There is no sign of that having calmed Red Star nerves, though, and three minutes later Nenad Miskovic is booked for a horrific lunge on Dragan Mladenovic.

Red Star are a very young side; their coach Zoran Filipovic freely admits he is looking to next season and beyond and, as the half wears on and the pace drops a fraction, Partizan’s greater quality in midfield begins to tell. Their captain, Sasa llic, is at the heart of much of their best football, and he shows supreme calm on the half-hour to slip the ball left in a crowded box to Ivica Iliev, who curls a chip beyond Ivan Randjelovic and inside the far post.

What it would mean to score against Red Star? Take my car, take my phone, take everything, just give me a goal

Before the game FourFourTwo asked Iliev, the wild child of Partizan, what it would mean to score. “Take my car,” he replied. “Take my phone, take everything, just give me a goal.” He celebrates by ripping off his shirt, and racing the length of the pitch and beyond to receive the applause of the Partizan fans.

The second half begins with another hail of fireworks and a flurry of yellow cards as Albert Nadj and the excellent Igor Duljaj are booked in the first minute. Red Star have regained the initiative, and only a superb save from Radisa Ilic, leaping up and to his left to push the ball onto the bar, keeps out a firm header from Nemanja Vidic. Seven minutes later, though, the visitors do regain the lead, Pjanovic bundling the ball in at the back post.

As the Delije celebrate, seats rain down onto the running track from the Partizan end. Their fury doesn’t last long, though. Iliev is everywhere, and it is from his cross just after the hour that Sasa Ilic turns the ball home to equalise. Ivan Gvozdenovic twice misses good chances for Red Star, but it is Iliev who comes closest to grabbing a winner, his angled drive smacking against the upright on 78 minutes.

Three minutes later Nadj picks up a second yellow card and Partizan, shutting up shop, withdraw Iliev. He stands by the end of the dugout, too keyed-up to sit, and continues to kick every ball. Partizan get their point, but only thanks to Ilic, who reacts superbly to tip a deflected Markovic shot over the bar.

A draw satisfies everyone. Partizan stay well clear at the top of the table, but Red Star’s youngsters leave with honour. Even the police are happy avoiding a full-scale riot is seen as a major achievement. “It is always a relief when it is over,” says Partizan forward Andrija Delibasic. “Then you start looking forward to the next one. The derby can be a game of dreams, but it can be a game of dread.”

This feature originally appeared in the March 2003 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe!

World's Biggest Derbies • More Than a Game