Wales v England, poor v 'rich' – it's Wrexham vs Chester

Ryan Reynolds and Rob McElhenney have been Wrexham's owners for years now, but it's important to know the local rivalries. Back in 2006, Andy Mitten went undercover in North Wales to meet two unfriendly neighbours...

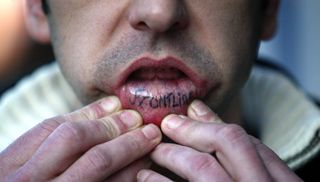

Wrexham’s Frontline hooligan firm have given FourFourTwo the nod to travel with them on the train to Chester, home of their most hated rivals. We’ve brought along a photographer, although it’s been made abundantly clear by our hosts that if things ‘go off’, then the camera will have to do the same.

On arrival in Chester, we will spend time observing a major police operation – one that has prevented officers from 50 miles away taking leave – to keep the rival supporters apart.

We’ll also meet fans from both sides of the divide, and while no Chester City or Wrexham fan pretends this is the biggest derby in football, they do believe the clash is genuinely more than a game. It’s a unique encounter, one that is as much about class and nationality as football.

Given that Wrexham have historically tended to play in a higher division, border skirmishes between the teams from middle-class Chester of England and working-class Wrexham of Wales are not played out with the regularity of other derbies.

So as the two clubs prepare to meet in the league for the first time in over a decade, the words ‘eagerly’ and ‘awaited’ begin cropping up in local papers as frequently as police warnings that any hooliganism will not be tolerated.

It’s 8.57am on Wednesday, December 28, 2005, a normal working day, when we walk into the cavernous Wetherspoons pub in Wrexham town centre. Inside, around 100 lads aged between 16 and 50 are already drinking. Most would happily classify themselves as members of the Frontline, a long-established group of wily casuals whose website opens to the Stereophonics song, As Long As We Beat The English.

One of Wrexham’s nicknames is the Red Dragons, yet the only evidence of red in this boozer is the discreet Prada Sport labels worn by many. A Wrexham fan in a replica shirt would look about as subtle as Santa Claus riding a cow in the Grand National.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

The intention is to get the 11 o’clock train 10 miles to Chester. The monied post-Christmas shoppers who flood the city will be in for an unpleasant surprise if they see Wrexham’s marauding mob. The police, who wait by the train station to escort the Frontline and prevent such an occurrence, are fully aware of the potential for disorder and have made the game a midday kick-off to reduce the probability of trouble. It hasn’t gone down well with fans who’ve had to take the day off work.

The English and Welsh police are co-operating closely, with intelligence officers monitoring the Frontline’s movements. At the moment, these consist of frequent visits to the bar. The leaders in the Frontline are doubtful that they’ll get a chance to attack Chester’s 125 firm, but they live in hope.

A gaunt and dishevelled figure enters the pub. He doesn’t look like he’ll make it to the bar, let alone Chester. He begins scrounging for money. The lads don’t give him any but they tolerate him, some even shaking his hand. “Twenty years ago he was one of the top lads in Wrexham,” explains one hooligan. “He always had the best trainers, girls, everything. He’s a smackhead now. Shame.”

If I hadn’t been nicked I would have probably left all this behind. But I’m back here now, aren’t I?"

The drug addict won’t be going to Chester but the violence addicts will, a band of brothers frisky with anticipation as they prepare to cross the border into enemy territory. Several have just come out of prison or finished banning orders for smashing up a pub opposite Chester station in 2004.

One has the incriminating CCTV footage that was used in evidence against the perpetrators on his mobile phone. It lasts for five minutes, as 20 or 30 deranged Frontline persistently attack the Deva Mail and Sports Club with bottles, poles and any other objects they can muster. “Cost me my flat and missus that,” says Chas, one of the main Wrexham heads. “If I hadn’t been nicked I would have probably left all this behind. But I’m back here now, aren’t I?”

"You have to expect the unexpected when Chester and Wrexham meet"

Chester and Wrexham haven’t met in the league for 11 years and it’s the Blues of Chester who remember the 1995 Valentine’s Day meeting more fondly than Wrexham’s Reds. Reduced to nine men, Chester came back from 2-1 down to draw 2-2 at the Racecourse Ground.

“I’ve never played in a game that had as much incident as that one – two sent off, a missed penalty and four goals,” says Gary Bennett, who turned out for both teams during a distinguished lower league career.

“Everyone in the Wrexham dressing room was gutted afterwards; we couldn’t believe how nine men had got a draw against us. The Chester fans were singing, ‘You couldn’t beat nine men',” adds Bennett, still revered as ‘Psycho’ by Wrexham fans.

“Every player who took part in that game is held in such a high regard by City fans,” says Chester fan Jim Green, “If Andy Milner ever falls on hard times I know 100 people who would give up their beds for him.”

Bennett has been on the winning side for Chester in the same fixture, too, a 1987 third round FA Cup tie. “It was snowing and Wrexham led 1-0 at the break – but I managed to get two second-half goals,” he says. “Wrexham fans always remind me of that one. I also played in a Freight Rover Cup game where fans were ripping up seats and throwing them. You have to expect the unexpected when Chester and Wrexham meet.”

I played in a Freight Rover Cup game where fans were ripping up seats and throwing them"

What you can always expect is mutual disdain. One Chester website has a section called ‘They’ve scored against the Wrexham’, which boasts: “In a perfectly ordered society, streets would be named after them. When it comes down to heroes they’re right up there with Spartacus, Hercules, Theseus and, yes, even Biggles. By scoring for Chester against our arch-rivals, the Goats, they have genius shining from every orifice.”

Goats is a favoured Chester moniker for Wrexham, along with ‘Wrectum’ and ‘Sheepshaggers’. Wrexham also use many colourful profanities to describe Chester, the least offensive being ‘Jester Pity’.

Back at the pub, bad news filters through: the game’s been called off. Chester’s pitch, which straddles the England/Wales border, is frozen. The reaction is surprisingly measured, probably because the news is not entirely unexpected. “Means the re-arranged game will be at night now,” offers one in consolation. “That means there’ll be a better atmosphere,” interjects another.

The Frontline considers going to Chester regardless, but the arrival of two police intelligence officers in Wetherspoons makes them reconsider. “Boys,” says an officer in a firm, businesslike tone. “We’re passing on a message from our Chester counterparts that resources will now be focused in the Wrexham area for the rest of the day.”

Nobody replies, but the few nods indicate that they’ve got the message loud and clear and the Frontline contemplates the long day ahead. They’ve got plenty of time – it’s not even 10am.

Wrexham’s population of 43,000 makes it one of the smallest places to have a Football League club. Only the towns of relative newcomers Yeovil, Rushden and Boston have fewer inhabitants. Wrexham grew because of industry, including brickworks, steelworks and a brewery making Wrexham lager.

Coal was also mined in several surrounding villages, including Gresford, famous for its colliery disaster of 1934. Yet mention Gresford to the Frontline and they talk about a riot that erupted during a 1990s Sunday League game between a Chester-based team and one from Wrexham after hooligans from both sides came to watch.

The 1970s offered mixed fortunes for Wrexham. The side played in the European Cup Winners’ Cup four times and reached the sixth round of the FA Cup twice, but the decline of the town’s traditional industries had a devastating effect. “I can remember my dad losing his job and we wanted to leave Wrexham to get a job elsewhere,” remembers one fan, “but everyone else wanted to do the same and house prices dropped so we couldn’t. Everyone in my school seemed to be on free meals. But dad still found money to take us to the match.”

"Wrexham see themselves as downtrodden, but parts of Chester are just as bad"

Wrexham’s economic situation has improved in the last two decades, but it remains the antithesis of well-heeled Chester. Many Wrexham supporters are happy that it stays like that and are proud of the hard-bitten reputation their town boasts.

Chester has never relied on traditional industries like Wrexham, instead hosting

a large white-collar workforce mostly involved in financial services. Chester’s

riverside setting, cathedral, Roman walls, and historic racecourse have long been

a tourist magnet. The clock on the town hall only has three faces, with the Wales facing side remaining blank because,

according to the architects, “Chester won’t give Wales the time of day.”

Everyone in my school seemed to be on free meals. But dad still found money to take us to the match”

An archaic but oft-cited law states that any Cestrian [a resident of Chester] may shoot a Welshman with a longbow if he loiters within the walls after sunset – although this law no longer offers legal protection against prosecution for murder. “I’d like to see them try it,” says one Wrexham lad.

“Wrexham boys see themselves and the town as downtrodden by the well-to-do of Chester,” says Jim Green, “but parts of Chester like Blacon or the Lache are as bad as Queens Park in Wrexham.”

Queens Park [remained Caia Park in an attempt to improve its image] is a troubled Wrexham estate of 14,000 which was plagued by riots between asylum seekers, residents and police in 2003. Some members of the Frontline were involved.

With a population of 90,000, Chester is over twice the size of its rival, yet their support is around half of Wrexham’s, partly because Wrexham attracts fans from all over North Wales. “The people of Chester don’t deserve a Football League club,” says Wrexham supporter Paul Baker. “Chester’s too posh for football. They’re into rowing, lawn tennis, golf and all that.”

Baker, who is unlikely to ever be employed by the Chester tourist board, continues: “The Cestrians are stuck up their own arses. Wrexham lads look out of place there. We wear sensible clothes; they wear pink shirts and have gel in their hair. We go out on the steam [drinking], throw it down us and have a laugh. They just want to have a drink or two and chat up the ladies. That’s why a lot of Wrexham girls go out in Chester – they like to be treated well and know we’re a bunch of piss-cans.”

One irony is that the Frontline fuel Chester’s prosperous economy by buying their designer threads in the city’s superior shops. “Most Wrexham lads buy their clothes in Chester as there’s more choice,” explains Irish, another Wrexham fan. “But even as a teenager the Chester lads would stop you and ask where you were from. You had to have your wits about you.”

And it’s not just Wrexham fans who question Chester’s support. When City were in turmoil under Terry Smith, the controversial American owner who briefly installed himself as team manager, Mark Lawrenson opined: “The trouble is that Chester is not a footballing city.”

“There was an outcry over Lawrenson’s comments but ultimately, as much as it pains me, he was right,” says Jim Green. “We’ve a population of nearly 100,000 within the city yet cannot pull in 3,000 for a league game on a Saturday. I think the council and the city in general lack the passion of our counterparts in Wrexham – something I’m pretty envious of. Wrexham could pull in over 10,000 every week if they were doing well, and previously have done just that – something Chester will never do.”

Until Hollyoaks, not many people outside the North West knew where we were"

Other Chester fans view it differently. “Try telling people that Chester is not a football city when witnessing the passion at a Wrexham derby match or the tears that were shed when we were relegated to the Conference,” says Sue Choularton of the Chester Exiles, a long-standing supporters’ group with 100 members around the world. “Lawrenson’s comments actually helped because they galvanised the Chester City supporters’ groups into action and ultimately led to the downfall of Smith.”

Green reckons there are differences in the identity of the respective populations. “North Walians see Wrexham as their identity – if you tell somebody you live in Coedpoeth, a village five miles away, then nobody has a clue where that it is, but people have heard of Wrexham. Chester, meanwhile, is a small city, overshadowed by Liverpool and Manchester. Until Hollyoaks, not many people outside the North West knew where we were.

"We’ve basically got five suburbs and that’s it – villages any more than five miles outside of the city prefer to have their own identity. It’s much more in keeping with the Cheshire mindset to tell people you live in Tarporley or Little Budworth than Chester, despite their close proximity.”

"I hate the police helicopter. It stops us doing anything"

Three months later, we’re back in Wrexham, this time for the visit of Chester. It’s late March and the teams have still to meet this season. A line of police riot vans is parked outside Wrexham General Station, just 200 metres from the Racecourse Ground. The police have again decided on a noon kick-off, but with daffodils hinting of spring in a blustery North Wales, there’s little chance of this game being called off.

Despite an abysmal run of form that has seen them plummet to 92nd in the Football League, Chester have sold 1,340 tickets and around 250 of the owners, among them known troublemakers, are due to arrive at the station half an hour before kick-off. They will be met by a unit of handy- looking police in body armour who look like they’ve spent more time filling in hooligans than forms behind a desk.

“Our job is to facilitate the safe passage of visiting supporters,” says one Robocop. “I used to work in a large Midlands city where we had serious problems. Now I’m based in North Wales where we get little storms in teacups. However, this lot need keeping apart.”

Aware that the police will prevent them getting anywhere near the visiting fans, the Frontline remain in a town centre pub. Some of them have hung a flag from a bridge of the Chester/Wrexham bypass to greet the visiting fans. It reads: “Welcome to Hell”, or at least it does for a short while before police remove it. There are even dark murmurings of bricking the train before it arrives, a little ironic on a train line that was built partly to transport bricks.

The vast majority of the 7,240 crowd, easily Wrexham’s biggest of the season in a stadium that holds 15,500, has no intention of causing problems. They hold the hooligans in contempt, pointing out that their cash-strapped clubs haven’t got the money to fund enormous police operations, evidence of which is everywhere.

I bit his City tattoo and it bruised for months"

Above in a dark grey sky, the North Wales police helicopter hovers loudly while dog handlers prevent groups of Wrexham fans forming on the ground. All the time CCTV cameras record events. Irish points to one whirring CCTV camera. “I hate that,” he says. “It stops us doing anything.”

He also identifies various individuals as they make their way towards the Racecourse Ground. “He’s a big Manchester City fan,” he says after shaking hands with a handy-looking lad who clearly doesn’t visit his dentist as often as he should. By that, it’s assumed that he’s Man City and Wrexham. “I once bit his City tattoo and it bruised for months,” adds Irish, who goes away with Manchester United. “A lot of the lads will watch Liverpool, Everton, United or City too.”

The lower-league club benefits from these two-team fans, who can often watch Wrexham at 3pm on a Saturday, and still fit in a trip to Old Trafford or Anfield for whenever television dictates kick-off time in the Premiership.

Five minutes before the Chester train arrives, Irish is back on his mobile. “The Frontline are coming up through the town now,” he says, visibly excited. Sure enough, police are soon holding all Wrexham fans behind a roadblock 100 metres from the station. They want the area cleared so that the English can pass.

“YOU MOVE – ESPECIALLY YOU!” bellows a policeman in a half-balaclava which masks most of his face. He’s talking to Irish. The Chester fans spill off the train into the station car park where they’re surrounded by police. “Ing-er-land, Ing-er-land, Ing-er-land!” they sing, a mixture of Burberry-clad lads and straight, scarf- wearing supporters. “Sheepshaggers!” they shout in the direction of the Wrexham mob behind the police lines.

“North Wales, North Wales, North Wales” respond the Wrexham fans. You hear Welsh spoken among some fans. “We’re proud to be Wrexham and we’re proud to be Welsh,” says Chas. “South Walians don’t always have it. They call us English or even Scousers, but for us it’s Wrexham first and Wales second.”

The police operation works impeccably, as the Chester fans are escorted down Mold Road into the away turnstiles. Five minutes later, the Wrexham fans are allowed to follow and they attempt to catch up, but like greyhounds chasing a rabbit, their target is always just out of reach.

Most of the Frontline stand in the seats adjacent to the away end which is named after former chairman Pryce Griffiths, a local businessman who has kept Wrexham afloat for much of the last 25 years. Griffiths was a fan who helped build terracing before he became a director in 1977, then chairman between 1988-2002.

Later made life president of the club, he remains popular, although some Wrexham fans criticised him following the sale of his shares to Alex Hamilton, the despised former chairman. Hamilton wanted to knock down Wrexham’s Racecourse Ground, their home since 1872, and replace it with a shopping development. This was the venue for the first ever Wales international in 1877, and is the ground where Anderlecht, Manchester United, AS Roma, Porto and Hadjuk Split turned up to play Cup Winners’ Cup ties, even if they left as soon as they could afterwards.

Because both fans have suffered from dodgy chairmen, a lot of the hatred is now being replaced by closet respect"

When protests put a stop to Hamilton’s plans, Wrexham slipped into administration and were hit with a 10-point deduction which saw them relegated to the league’s basement division at the end of last season. Still, at least the relegation meant that Wrexham got to renew their bitter rivalry with the enemy from across the border.

Like many rivals, the two sides have more in common than they’d like to admit. Despite their proud histories, both have recently been threatened with extinction because of serious financial problems. “Because both fans have suffered from dodgy chairmen, a lot of the hatred is now being replaced by closet respect,” says Chester fan Nigel Hutt. “There are many on both sides who hope that both clubs survive their problems.”

Jim Green agrees: “I have the greatest sympathy for what Wrexham have gone through over the last 18 months, having been there myself. I truly hope that they get through it – so we can stuff them next season.”

The feeling, however, isn’t always mutual. “I’d rather Chester didn’t exist at all,” says Wrexham fan Paul Baker. “I despise the club and a city which is full of people who are full of themselves. At the very least, I want Chester to go down.”

In the weeks leading up to today’s game, Chester, whose record transfer fee received is still the £300,000 that Liverpool paid for Ian Rush in 1980, have suffered an alarming slump, losing 12 games from 14 and slipping from sixth – a play-off place – to bottom of League Two, perilously close to the Conference league which they left as champions in 2004. You know a club is struggling when the players registered as numbers 35 and 36 are in the starting line-up.

Their current malaise is evident from their deflated, woeful performance in a first half dominated by Wrexham, who take a two-goal lead and see a penalty saved. Wrexham’s second goal is greeted by a stirring terrace chant, fittingly enough sung to the tune of Men of Harlech: “Wrexham Lager, Wrexham Lager, feed me ’til I want no more, feed me ‘till I want no more.” They even sing happily along in the posh seats.

“Wrighty, Wrighty what’s the score?” they add, pointing in the direction of Chester manager Mark Wright. In his second spell as manager, the former Liverpool and England defender looks forlorn. “Going down, going down, going down,” add the Wrexham fans, from behind advertising hoardings for roof trusses, printers and plastics. “Going bust,” retort the Chester fans in the Eric Roberts (Builders) stand, unfurling a “Goatbusters” flag.

Chester’s second-half performance is more spirited and they pull a goal back through Jake Edwards in the 89th minute. A chance of Cestrian immortality beckons for Paul Ellender, but he squanders a last-minute chance from six yards out.

Wrexham fans applaud at the final whistle, waving flags of St David in the direction of the visitors. Yet the Chester fans congratulate their team, too – they’ve witnessed a spirit absent in recent months. The police helicopter reappears above. The Frontline leaves the ground and cram round the exit from the away end. Hoods go up and caps go down, but the police have got everything under control and start pushing them back. Even the hooligans’ shouts of “Stand!” are frustratedly half-hearted.

As we wait for the Chester fans to be escorted back to the train station, two lads clock the photographer. “Are you FourFourTwo?” They’re keen to talk, but don’t want to give names. “I’m 49,” says one. “I did all the getting married, having kids and foreign holidays, but I got bored. I missed this. You can’t beat following Wrexham. We know Wrexham is a s**t-hole, but we’re proud of what we’ve got, proud of the number of lads who follow the team for the size of the town. Chester is bigger and our support is twice theirs. They don’t want a football team in Chester.”

The Chester fans are soon being escorted past the Turf Hotel in the corner of the ground where we’re stood. “Sheepshagging bastards,” one shouts. A lone Wrexham lad lurches forward. “Come on then,” he taunts. A policeman pulls him to one side for an explanation. “Look, there’s hundreds of them and about 10 of you. My shield is not going to offer much protection is it?” The lad takes his point and walks away.

We know Wrexham is a s**t-hole, but we're proud of what we've got"

“The police have got it organised today,” notes the ageing hooligan. “We’d absolutely slaughter them if we could get near, but I can remember Chester coming here and running us all over the place,” he says.

“No they didn’t,” objects his mate.

“They did.”

“Chester have never done Wrexham.”

“They have.”

This one, it seems, will run and run.

Wrexham-Chester pictures Jason Lock. People in pictures may not be hooligans.

Andy Mitten is Editor at Large of FourFourTwo, interviewing the likes of Lionel Messi, Eric Cantona, Sir Alex Ferguson and Diego Maradona for the magazine. He also founded and is editor of United We Stand, the Manchester United fanzine, and contributes to a number of publications, including GQ, the BBC and The Athletic.