War, English influence and a triumphant fight for freedom in Turkey: the Harrington Cup

As English Premier League giants Arsenal and Tottenham both descend on Istanbul this week, Paul Sarahs recalls what is locally seen as an even more signicant match involving the English in the city - one imagined by a war general...

It was a month before the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne, marking the end of the Allied occupation of Istanbul, and the Republic of Turkey was emerging from the crumbling, putrefying ruins of the 700-year Ottoman Empire.

June 1923, more precisely. A force totalling more than 3,500 British, French and Italian soldiers had occupied the European side of Istanbul for nearly five years, since the cessation of hostilities in Europe.

The Turkish Grand National Assembly had abolished the Ottoman Sultanate the previous November, with the last Sultan Mehmet Vahideddin exiled to Malta on the British warship Malaya.

Throughout the occupation, Turkish clubs played exhibition matches against mostly British forces, faring well against the men who some players from Istanbul’s big teams battled during the week. Fenerbahçe alone played some 50 games, losing just five in as many years.

The final match played between the Allied troops, under the command of General Charles Harrington, and Fener, was to leave an indelible print on the history of both the burgeoning Republic of Turkey and the sports club, Fenerbahçe.

More than a game

The Turkish club's players were actively participating in the conflict while still representing the club on the pitch. Occupying forces were aware of Fener's role in the movement of arms and supply of men, raiding and occupying the club’s training facility for a number of days, but ultimately finding nothing incriminating.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Fenerbahçe had already defied Ottoman regulation upon their founding in 1907, when three men formed the club secretly to bypass strict rules. Football had arrived in Moda on the Asian side of the city in 1900, brought by the British but eyed with suspicion by the Ulema, a body of Islamic scholars charged with the moral upkeep of society. Turks were forced to play in secret, representing Istanbul’s first club, Black Stockings, clandestinely.

Teams were established for the English, Greeks and other minority groups without political interference, but Black Stockings’ first match was stopped by the police and the players were indicted.

The club ceased to exist less than a year after being founded by one of the four signatories of the ill-fated Treaty of Sévres, Riza Tefvik, who later faced 20 years in exile after being named as one of 150 persona non grata of Turkey.

When the Young Turks – a political reform movement intent on replacing the autocracy of Ottoman rule with a constitutional monarchy – took control in 1908, regulations regarding football in Istanbul were relaxed.

The sport, along with certain aspects of society, flourished as a series of political and social reforms saw vast improvements in communications, town planning and education – particularly for girls. Istanbul’s three behemoths had already been established, though they were forbidden from playing in the newly founded city league.

Two Englishmen, James Lafontaine and Henry Pears, had established the Constantinople Football Association League in 1904 as the Istanbul Sunday League, and its early editions were contested by just four teams. Three of them were set up by Englishmen. The Greek community set up the fourth, Elpis FC.

Turkish clubs had to wait until 1909 to claim their first victory in the Istanbul League, and subsequently dominated until the establishment of the national league in 1959. Fenerbahçe and fierce rivals Galatasaray each won the competition 15 times.

The right kind of clash

The Mustafa Kemal-led resistance was ultimately successful, with the signing of the treaty of Lausanne in July of 1923 establishing the Republic of Turkey and setting a timetable for the removal of Allied forces from the city of Istanbul.

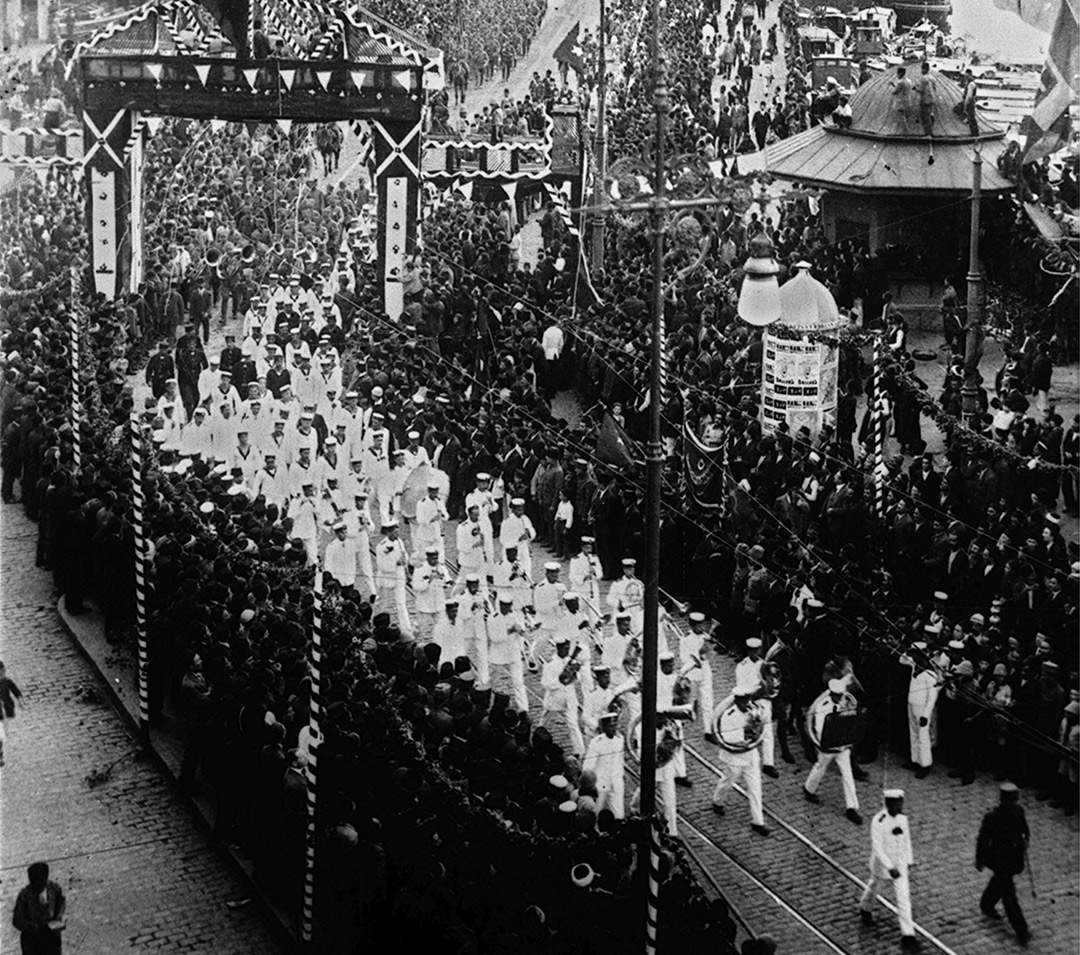

Before they departed, though, there was to be another clash – this time at Taksim Stadium.

General Charles Harrington, a veteran of the Second Boer War, a highly decorated military leader and Commander-in-Chief of the occupying forces, had taken out an advertisement in an Istanbul newspaper challenging the city to a football match against his team of Allied soldiers from the Grenadier, Coldstream and Irish Guards.

"The Joint Guards challenge Turkish clubs to a football match," read the advertisement. "The Turkish clubs can call any players into their team for this game, and the winner will be awarded a trophy which will be named after the Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Forces."

Harrington's aim was to leave the city of Istanbul for the last time having inflicted a heavy defeat on the local team.

“Fenerbahçe accept this proposal, unconditionally, using only our own squad,” came the response the following day.

The match took place at Taksim Stadium, now Gezi Park, on the European side of the city. Fenerbahçe would go on to win the Istanbul League in the 1922/23 season, scoring 53 times without conceding a single goal, boasting the left-footed goal-machine Zeki Riza Sporel and captained by his brother Hasan Kamil.

The Sporel brothers would further cement their legendary status in Turkish football later that year when the national team played their first-ever match, again at Taksim Stadium, with Hasan Kamil captaining the side and Zeki Riza scoring both goals in a 2-2 draw with Romania.

Turkish delight

It was Zeki Riza Sporel who would decide the General Harrington Cup, too. Scottish winger Willie Ferguson – who would later go on to play almost 300 games for Chelsea – opened the scoring in the first half in front of a packed Taksim Stadium, with General Harrington joined in the VIP section by the Governer of Malta, Lord Herbert Plummer, with whom he had served in the Second Boer War.

In 14 second-half minutes, Zeki Riza turned the game. Equalising shortly after the hour mark, he then fired Fenerbahçe into the lead with 15 minutes remaining, ensuring that his brother lifted the metre-tall General Harrington Cup.

Almost a century later, the cup retains pride of place in the trophy room at Fenerbahçe's museum. It's a victory that resonates to this day on the Asian side of the city, a symbol of how a football club resisted occupation and helped a nation to its independence under the Father of the Turks, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.