Welcome to Miami? The bruising story of David Beckham's battle to become football's first superstar owner

His quest has been plagued by problems and setbacks, but that’s never stopped him before. This is the story of Becks's turbulent journey from bootroom to boardroom...

Since this story first appeared on the cover of FourFourTwo in August 2018, Beckham’s Miami franchise has been christened as Club Internacional de Futbol Miami – or simply ‘Inter Miami’ to you and FFT. Now, read on...

During the week of David Beckham’s final appearance for LA Galaxy in the 2012 MLS Cup, the 37-year-old player made a scheduled appearance in the media room at the StubHub Center. Displaying that well-honed projection of shy steeliness that has become his public-speaking trait over the years, Beckham held court about his time on the pitch in Los Angeles as he contemplated heading into his last ever match with the team.

The desk in front of Becks was littered with journalists’ dictaphones and smartphones set to voice memo mode. At one point, one of the phones rang with an incoming call. Beckham smiled along with the press pack at the interruption and joked, “Do you want me to answer it?” Then, spurning the chance to join what’s since become one of the recurring comic memes of the modern game, he quickly put the phone down and giggled, “It’s not Samsung – sorry, I can’t.”

It’s a moment that still resonates when you wrestle with Beckham’s legacy so far in the United States. For any other footballer, that kind of comfortable attendance to brand ethics could have seen him dragged in the media as everything-that-is-wrong-with-the-modern-game™. For Beckham, though, it’s a mode that’s long been accepted as coming with the territory – over the years he’s somehow managed to turn his incredible personal portfolio of business interests and profile-building into a virtuous sign of his work ethic.

Beckham and long-time business manager Simon Fuller have seen to it that the many hours he’s spent posing for photographers have fed the popular reverence for his hard work as much as those spent pinging free-kicks after training. In many ways, that’s a studied part of David Beckham’s legacy – his insistence on the bigger picture in all things frames the conversation for his critics, too.

You could have a perfectly valid technical criticism of late-period Beckham’s perception of himself as a Tom Brady-esque quarterback, for example, by pointing out the excessive running and tackling his team-mates had to do to make up for Beckham languidly occupying the pocket he sprayed his passes from. But you’d always be aware, or soon be made aware, that without Beckham there would be no Thierry Henry, Zlatan Ibrahimovic, Steven Gerrard, Andrea Pirlo, David Villa nor Kaka in MLS. Perhaps no modern MLS as we know it.

So assessed with one lens, he did fine (two MLS Cups in five seasons without ever personally making himself a MLS legend for his exploits as a player). Assessed with another, he fundamentally transformed the game in America. That suits him fine.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

And now, never mind what he did on the pitch, David Beckham is trying to build a club of his own…

A world before Beckham

First, a hint of historical context. The single-entity structure of Major League Soccer means players sign a central contract with the league, rather than negotiating strictly with an individual team. When Beckham was unveiled as an LA Galaxy player early in 2007, the fact that this contract included a future option to exercise an MLS franchise at a fixed cost of $25 million was remarked upon as a kind of vanity concession, and not seen as the bargain it looks today.

MLS, at that stage of its history, was in a far more precarious place than it is now. The fledgling league had already made a few gauche mistakes in its initial incarnation after the 1994 World Cup. The legacy of penalty shootouts, countdown clocks and other novelties inserted in pursuit of a suburban market had blighted the league’s credibility with more serious fans in and beyond the USA, without building the kind of anticipated fan loyalty to appear sustainable. And when the post-9/11 economy took a nosedive going into the 2002 season, the league even faced the possibility of folding.

Prior to that campaign, the league’s owners and recently-installed league commissioner Don Garber met at a hastily convened summit and agreed on drastic emergency measures. The two sides struggling in Florida’s fickle market, Miami Fusion and Tampa Bay Mutiny, were to close immediately, essentially losing an arm to save the body. The 10 remaining teams would be consolidated under the ownership of Phil Anschutz’s AEG group, the Hunt family, and Robert Kraft.

Elsewhere, a marketing arm for MLS and US Soccer, Soccer United Marketing (SUM), was set up to help bring in additional television and marketing revenue.

Under the new arrangement, Anschutz now owned the majority of teams in the struggling league. He also agreed to invest in a stadium for one of them – LA Galaxy. This being before the days of the league insisting on downtown locations as a prerequisite of expansion deals, he erected the then-Home Depot Center (later StubHub Center) in the bland LA suburb of Carson, and he and his fellow sports industrialists dug in for an expected long journey back to solvency.

A few years later, at the moment when an ambitious AEG executive, Tim Leiweke, pursued and then landed Beckham, progress had been slow. The two teams lost during the 2002 contraction had eventually been replaced in 2005 by Real Salt Lake and an awkwardly conceived spin-off of Mexican giants CD Chivas Guadalajara, called Chivas USA. The former are a vibrant but decidedly small-market team, while the latter existed as awkward room-mates at LA Galaxy’s new home and, following an ill-starred and frequently ill-defined decade, would also fold towards the end of 2014.

The turning point

So how did we reach the current mode of rapid expansion? If you ask league insiders today about that period, they’ll talk about 2007 as the inflection point – an account that sits well with the announcement on January 11 of that year that David Beckham would be swapping Real Madrid for the Galaxy. But the bigger structural moves, and the ones that Beckham and Fuller’s 21 Management have evidently monitored all along, were already happening. By 2007, Anschutz had begun the process of divesting his ownership of teams – most notably flogging his New York team, the Metrostars, to the Red Bull group in March 2006. And perhaps most significantly of all, the huge Canadian sports group Maple Leaf Sports & Entertainment Partnerships (MLSE) made the decision to invest in an MLS franchise in Toronto, who debuted three months after Beckham’s announcement.

And while that team would face an arduous journey to their current reputation as perhaps the best MLS side ever assembled – existing as a byword for on-field dysfunction for much of the first decade of their history – the symbolic presence of MLSE immediately loomed large for potential investors.

There was, after all, something of a noblesse oblige spirit about that first generation of Anschutz, Hunts and Kraft circling the wagons as the league haemorrhaged money – sports industrialists protecting their legacy as much as their bottom line.

But MLSE and Red Bull, or new major sponsors such as Adidas, had no sentimental stake. If they saw an upside, ran the investor logic, the future might be bright after all. That, more than even the high wattage star power of Beckham, was the starting pistol for the current period of expansion. That’s not to disrespect or downplay Beckham’s influence or cultural significance of his contribution. It’s simply to note that it’s clear the player and his team fully appreciated themselves – cultural capital doesn’t build stadiums.

But it could buy the discounted right to. And in inserting a clause in his initial MLS contract allowing him to purchase a future franchise for $25m, Beckham, as always, had his eye on the bigger picture.

Welcome to Miami

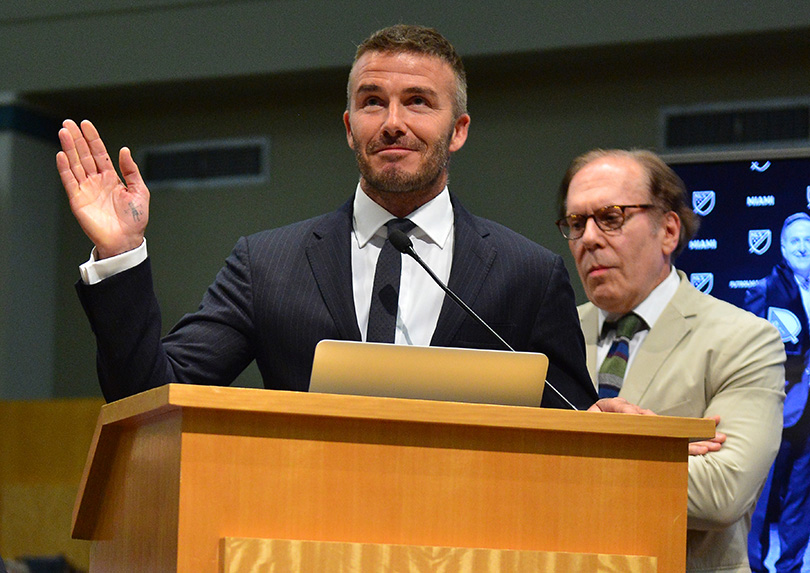

When Beckham sat on a stage with Mayor Carlos Gimenez of Miami in January 2014, to announce that he had exercised his contractual right to an expansion option by selecting Miami as his chosen city, the ex-player’s star power was in full effect. The mayor was grinning widely at the political coup, and the footballer was full of modest charm and well-aimed platitudes. And if the project sounded long on ambition and short on detail, so what? Details could be ironed out.

However, as the months and eventually years passed by, a deeper unease began to attach itself to the project — an unease that had as much to do with Miami and Miami politics as it did with Becks’ ability to engage with the same.

At times the dynamic seemed reminiscent of the scene in 1999 film Any Given Sunday where Cameron Diaz, heiress to the fictional Miami Sharks NFL team, finds herself being lectured to by the mayor as she agitates for stadium funding: “You are a relative babe in this town. Go slow. First you get along, then you go along.”

Time and again, Team Beckham tried to pin down possible stadium sites sheerly through the power of Beckham’s celebrity, only to rapidly run into unimpressed realpolitik of getting things done in a contested corner of South Florida.

Occasionally Beckham has appeared to be on a learning curve about where and how to leverage his presence as a now ex-player. So he would make a noticeable courtside appearance to watch LeBron James play for Miami Heat, for example, and would prominently seek out LeBron’s counsel. King James, meet King David. However, Becks might have been better served chewing the fat with Micky Arison, who owned both Miami Heat and the Carnival Cruise group operating out of Miami near the Heat’s downtown waterfront arena.

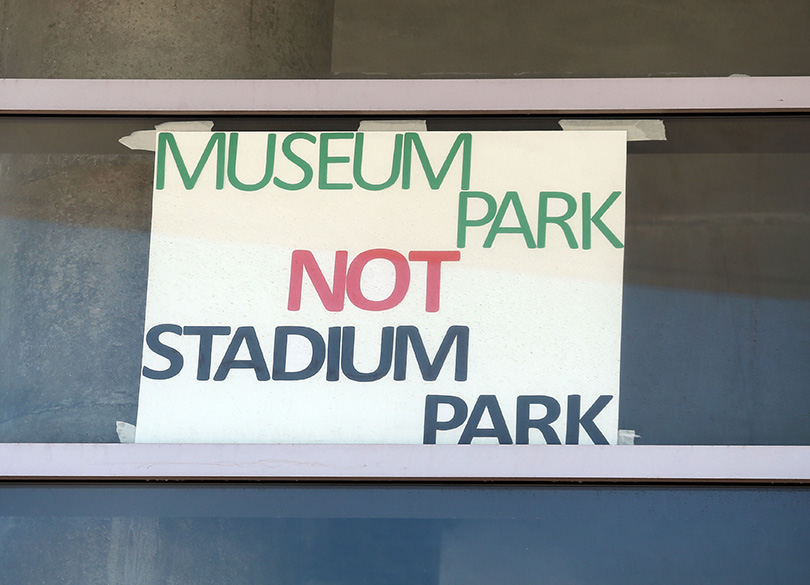

When Beckham and his associates eventually picked a particularly ambitious waterfront stadium site of their own in 2014, they quickly found themselves dashed by myriad groups. They included objections from cruise companies and smaller businesses, plus a gun-shy local government who were reluctant to make any funding concessions on a new stadium deal.

Miami’s history of sports, and especially sports business, has tended towards the toxic – in fact, the city having already lost an MLS team merits barely a footnote in that history. Arison’s deal with the city for his basketball arena had attracted its fair share of criticism, but by far the greatest shadow over Beckham’s ambitions was the Florida Marlins.

The Marlins’ stadium deal has since become a byword for lopsided public-private funding disasters, and all talk around Beckham’s Miami plans have inevitably been coloured by the experience.

In short, the Marlins’ ownership managed to persuade Miami-Dade County to put its residents on the hook for an eye-popping $2.4 billion in compounded repayments, for a new baseball stadium in the city’s economically depressed Little Havana neighbourhood.

The stadium deal offered economic vitality for a neighbourhood around a flagship ground showcasing a winning team, celebrating Miami’s sporting vitality. Instead, upon completion of the venue, the ownership promptly commenced a fire sale of the team’s best talent, never to be replaced. The team remains mired in mediocrity, while the taxpayers remain mired in debt.

It’s no wonder that Miami Beckham United has struggled to get any traction with the city’s politicians – with many mindful of the fate of Miami-Dade County mayor Carlos Alvarez, who was recalled by voters in the wake of the Marlins scandal.

Uphill struggle

Where Beckham and his team have not always helped themselves is in appearing to underestimate the nature of that battle. The initial high-profile scouting missions and selfie opportunities, prominently featuring Beckham, seemed to dwindle as the project stalled.

At the moments when they needed a political offensive more than a charm offensive, city officials seemed mildly bewildered at the lack of contact not just from Beckham, but from the telecoms billionaire backing him, Marcelo Claure. Not for the first time in his career, Beckham had found himself being dismissed as more front than substance.

The league appeared to be getting a tad agitated, as well. No press conference for Don Garber could pass without the obligatory Miami question, though the line of questioning morphed from “What’s the timetable on getting this done?” to “How much time are you prepared to give him to get this done?”

Meanwhile, the league’s expansion process continued apace. It was accelerated by a divestment process by AEG and the Hunt family that left each group with only one side apiece, and the league dealing with a culture shift towards a generally younger, entrepreneurial group of owners. They were now paying the type of expansion fees that made Beckham’s $25m look like an absolute bargain.

By the time New York City FC and Orlando City entered the league in 2015, the price of a seat at the table had risen to $100m. And when heavy-hitting Atlanta Falcons NFL team owner Arthur Blank entered the fray with Atlanta United in 2017 – promptly smashing attendance records – and a second LA team was introduced at a gleaming new downtown stadium in 2018, the lingering option retained by Beckham stood out on the landscape.

On the one hand, it now seemed like incredible value for the player and his team, and a loss leader for the league; on the other hand it was a project that could never seem to build momentum to cash in on that value. And while the league never publicly admitted as much, the value of Beckham himself was a less certain quantity now that he wasn’t doing the thing which gave his brand meaning.

Don’t underestimate

But underestimate Beckham’s resilience at your peril. It can be easy to forget the moments throughout his career when his position has looked untenable, such has been Becks’s ability to endure.

The tour of vitriol he suffered at Premier League stadiums after his 1998 World Cup sending-off against Argentina ended with him guiding Manchester United to an unprecedented Treble the following season. Cast adrift at Real Madrid following the announcement of his move to LA, meanwhile, he fought his way back into Fabio Capello’s line-up and ensured he bid farewell to the Bernabeu with his first and only La Liga title winner’s medal.

Even in America, when he was subjected to boos by LA Galaxy supporters after trying to make his 2009 loan move to Milan permanent (AEG forced him to honour his MLS contract), Beckham dug in and fought back to rebuild his reputation and secure two MLS titles with the Californian club.

And now, with a stadium site finally secured (at least barring final legal challenges) in Miami’s Overton, Beckham’s Miami team was confirmed as a reality this January. More backers are on board, and the team will kick off in the 2020 campaign.

In some ways, perhaps, the most dangerous part of the project for Beckham personally is done and dusted. The anonymous business of land scouting, financing, political negotiations and appeasement has almost been completed. Now Beckham is thrust back into a familiar role as a public asset, there to embody the envisioned glamour of the project and to attract talent and further investment to it.

Now to build with a Miami flavour. The twin engines of MLS growth in the last 10 years have been millennials and Latinos, and certainly the latter are a prominent target demographic, particularly given the sizeable South American influence on South Florida. Downtown Miami has also been revitalised with youth-led creative industries. Culturally, the Miami Basel art fair is now an annual fixture of the international art calendar, whose travelling circus has trailed significant investment from wealthy collectors. Real estate speculation is almost a sport in its own right there.

In that light, the more feverish transfer rumours suggesting Cristiano Ronaldo as the ideal marquee signing for the expansion team make a certain sense. In 2020, he will be of an age (35) where a last big move may appeal, with enough miles still in the tank to become the type of foundational presence David Villa has become for NYCFC in their first years.

The Portuguese’s preening presence would unquestionably be in its natural habitat in South Beach, if not Overton. As with Becks himself, Miami would seem on the surface like the cultural fit. Thinking along those lines, you could easily extrapolate an image and profile of the new team to make the right splashdown, and you suspect Beckham will put few feet wrong on that front.

The lingering questions are the prosaic but essential ones that make clubs bed in and sustain, however, so that’s where Beckham’s tenacity and attention to detail must come into play as never before.

The legal disputes over the Overton stadium site may be resolvable, for example, but reflect some local disquiet about the tight nine-acre location for the ground. Do Beckham and his team have the type of granular sensitivity required to keep the community onside?

There are questions, too, about how loyal Miami supporters will be when the novelty wears off. Even in LeBron James’s heyday in the city, the Heat didn’t always attract the type of sustained support they may have expected, and there’s a lot of weight on Beckham to deliver as the centre of gravity for a start-up team. Especially somewhere where lifestyles of conspicuous consumption do not necessarily translate to conspicuous loyalty.

Then there’s the passing of the Designated Player era that Beckham himself ushered in. When he arrived in the strictly salary-capped MLS, the rules had to be changed to pay his wages, and for a brief period his Galaxy team were the model for top-heavy sides built around the talents of the three Designated Players each MLS side was permitted.

However, with rule changes to salary cap and discretionary spending allowances changing the balance of teams, and with the academies forming an increasingly important part of top team strategies, current best practice in MLS is less about star power than smart investment and sustainability. It’s a sober mode that doesn’t necessarily tally with Beckham’s unique selling points.

And on an even bigger-picture sustainability note, the low-lying city of Miami is on the global warming frontline and routinely tormented by high tides over-running the storm drains. The forward-thinking of 2007 might have to be reassessed in 2027 if it transpires that even David Beckham can’t turn back the tides.

That’s for others to figure out, though. Right now, Beckham is focusing on what he can control. History suggests that we’d be foolish to bet against him.

This feature originally appeared in the August 2018 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe!