Wembley: born of folly and almost destroyed after two years

The early history of English football’s home was anything but promising, reports Paul Simpson.

"Oh bygone Wembley, where’s the Pleasure now?” That capped P on Pleasure is a sign that this lament is not from a football fan nostalgically recalling past triumphs at the stadium but from John Betjeman, one-time Poet Laureate and chronicler of a nondescript part of northwest London dubbed Metroland after the Metropolitan train line that has run through it since the late 19th century. Here, in this suburban nowhereland, it was decided to build Wembley stadium, the home, heart and capital of English football.

“Decided” might be putting it too strongly. The building of the stadium was brilliantly efficient – it finished on time and on budget and was thoroughly tested by 1280 builders, drilled by one Captain FB Ellison, who stood up, sat down, swayed from side to side and backwards and forwards, jumped up down while shouting and waving and ran up and down several flights of steps.

Yet the process by which the stadium came to be located at Wembley was circuitous, owing something to a tycoon’s hubristic visions, the unpredictable tastes of the British public and the need to find somewhere for the British empire to congratulate itself on surviving, just about, the First World War.

Building the English Eiffel

The small village of Wemb Lea, as it was first known, was founded in 825. For the next 1,000 years, virtually nothing happened there. In his 1973 TV documentary Metro-Land, Betjeman says: “Beyond Neasden, there was an unimportant hamlet where for years the Metropolitan didn’t bother to stop. Wembley. Slushy fields and grass farms.”

This hamlet became important in 1890 when Liberal MP, railway tycoon and all-round visionary Sir Edward Watkin decided to build a tower here – one so tall it would make the Eiffel Tower, completed the year before in Paris, look downright diminutive.

At sleepy Wembley, Watkin decided to build a tower so tall it would make the new Eiffel Tower look diminutive

Why did Watkins choose this sleepy rural spot? The land was so far out in the sticks it was cheap – and plentiful. Plonk some houses down, provide a railway to service it and, hey presto, you have a suburb!

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

If you can sell the houses too, you’ve got yourself a nice little earner. Eventually, this is what the company that built the tower had to do to make a profit. Yet initially, Watkin’s rationale was simpler: given his grandiose plans, he needed to spend as little on land as possible.

His plan to expand the Metropolitan railway past Harrow, out to Wembley and beyond, needed a gimmick. A big one. Which was fortunate because large gimmicks – attempting to dig a Channel Tunnel and build a new seaside resort in Dungeness being just two of his startling ideas – were what the septuagenarian Watkin enjoyed most at that point in his life.

Like many radical businessmen of the Victorian era, he wasn’t driven entirely by ego or profit. A reformer in Parliament, he had an entrepreneurial vision driven by the desire to create a better, newer world. Ultimately, he would prove too original, versatile and audacious for his own good.

The wally with the folly

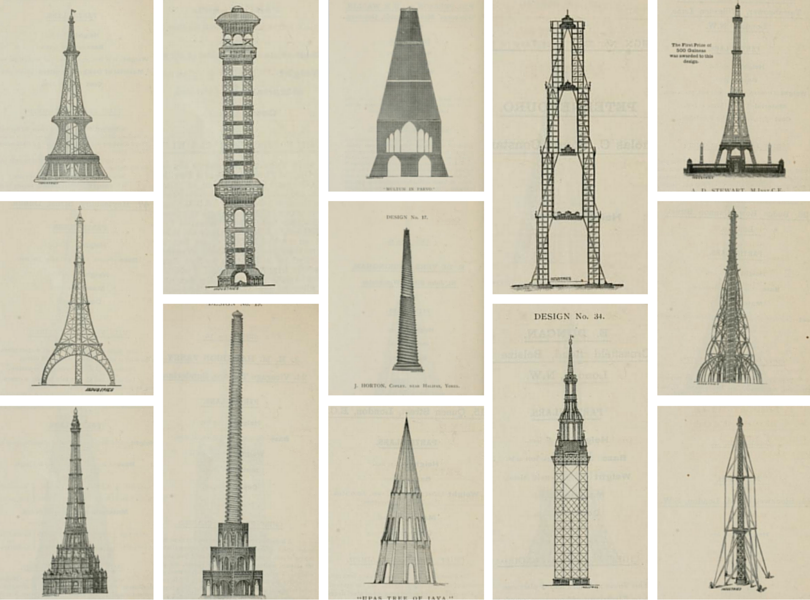

Watkin’s tower was envisaged as the central attraction at a proto-theme park, decked out with boating lakes, waterfalls and cricket pitches. He asked Eiffel to design it, but the civil engineer decided, as a patriotic Frenchman, that this was one commission he could not accept. So Watkin held a competition for the best design.

Some submissions were bizarre. The most outlandish featured “a captive parachute (to hold four persons)”; a vertical village with flats, offices, pubs, courts and a library, and hanging gardens so that a colony of aerial vegetarians could grow their own food while contemplating a 1/12th scale model of the Pyramid of Giza. The projects even had absurd names, notably the Circumferentially, Radially and Diagonally Bound Tower.

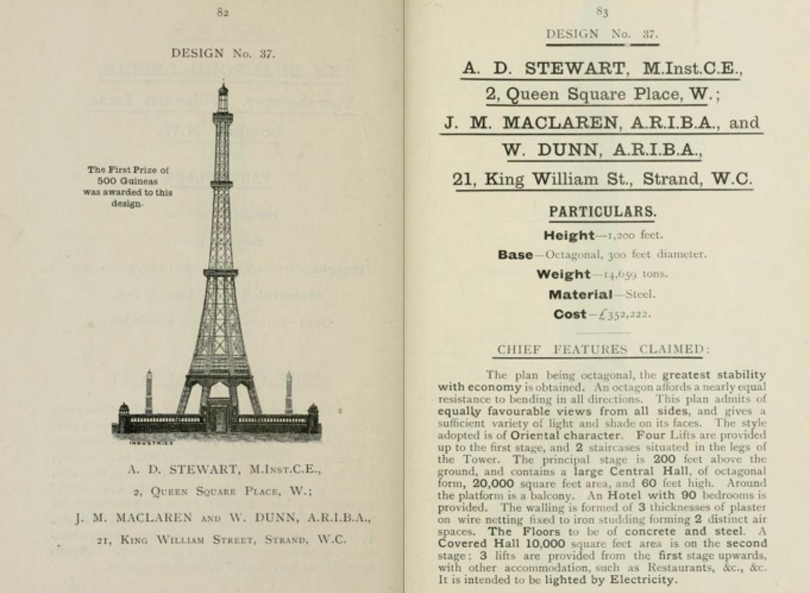

Bearing a suspicious resemblance to the Eiffel Tower, the winning design, submitted by architects Stewart, MacLaren and Dunn, would stand 1200ft (366m) tall, 150ft (46m) higher than its Parisian rival, with an observatory at the top because, it was proclaimed, “freedom from mists at that altitude would mean the stars could be clearly photographed.”

There were plans for shops, restaurants, Turkish baths, a theatre, a sanatorium but not, ironically, a football pitch – a curious omission given that Wembley Park station, which opened in 1893, had, at first, opened only to service local matches.

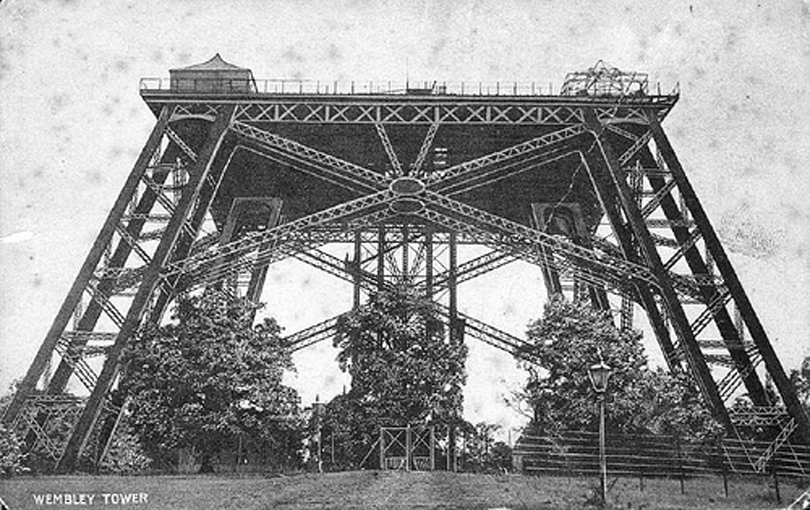

Although Watkin’s (partially-built) tower opened in May 1894, attracting 12,000 visitors in its first full year, it was not on the scale that its creator had envisaged. The foundations for the four-legged iron tower soon proved unstable and it never soared any higher than 154ft (47m). The public got bored.

The money ran out by the end of 1894 and, as construction stopped, Watkin’s creation was derisively dubbed the London Stump, Shareholders’ Dismay and Watkin’s Folly. As Betjeman put it: “The tower lingered on, resting and rusting, until it was dismembered in 1907.” Watkin didn’t see this final indignity; he died six years earlier at the age of 81.

Saving Wembley from dynamite

By then, the company that made the tower had already begun building homes to make money. “Each one,” Betjeman wrote, in affectionate mockery, “slightly different from the rest, a bastion of individual”. The business flourished but they owned enough land locally to sell it to the government-backed company staging the British Empire Exhibition in 1924 and 1925.

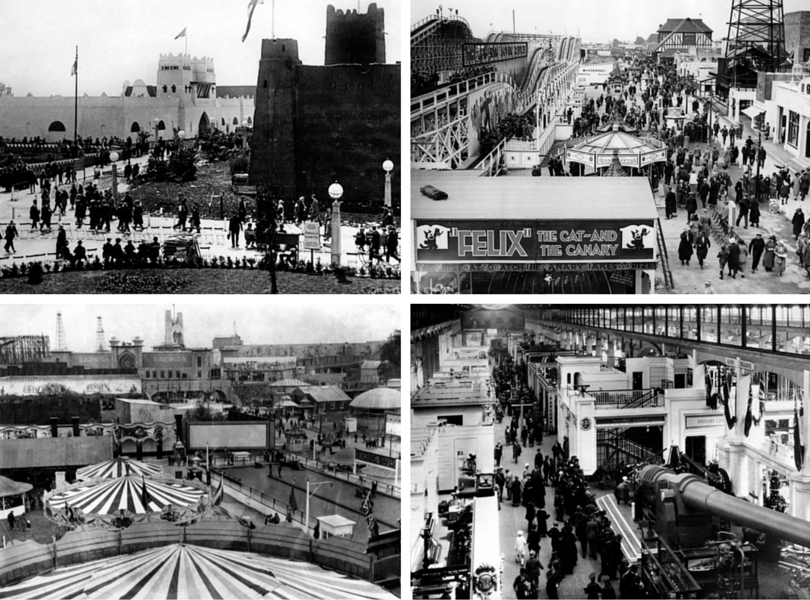

Though best known today as the event where the future King George VI stuttered so badly he finally saw a speech therapist, the exhibition was a jamboree designed to reinforce the bonds “that bind the Mother Country to her Sister States and Daughters”, attracting millions of visitors and popularising its very own song Wembling At Wembley With You.

The decision to build the Empire Stadium, as it was then known, looks more significant now than it did then. Even with its iconic 126ft-high Twin Towers – built with a new, improved form of concrete! – the ground was just one of many attractions, including a pageant of empire that starred 15,000 amateur actors, 730 camels and a macaw.

Betjeman was enthralled by the Pleasure Gardens – hence that capital P after “melancholy Wembley”. Even though the stadium hosted two FA Cup finals, the official plan was for it to be demolished, like most of the other attractions, once the exhibition was over.

A Scotsman, Baron James Stevenson of Holbury, saved the home of English football. An influential civil servant, past adviser to Winston Churchill and a chairman of the standing committee that organised the British Empire, Stevenson could not bear the thought of this stadium – “a dream of empire, made in concrete” as Betjeman called it – being torn down. A formidable operator, Stevenson saved Wembley from being dismembered by dynamite, as Watkin’s Tower had been.

It would take another entrepreneurial genius, tobacconist Arthur Elvin, to make the stadium financially viable. Yet he, Stevenson and football were all, in a sense, building on the foundations laid by Watkins’ failure.

Without his magnificent, flawed dream, millions of fans would not have gone Wembling at Wembley. So it seems only apt that when the builders knocked down the old stadium in 2002, they uncovered the foundations of Watkin’s Tower, laid with such heady optimism more than a century before.

#FFT100STADIUMS No.3: Wembley

#FFT100STADIUMS The 100 Best Stadiums in the World: list and features here

OTHER FEATURES

- The 11 weirdest stadium names

- What's the biggest football stadium in the world?

- In memoriam: 10 of England's beloved, long-lost grounds

- How to build a new stadium – by those who have

- Meet Archibald Leitch: The man who invented the football stadium

A brief history of football grounds

Join The Club

Join The Club