THIS is what being a fan in the 1980s was like – and what the Hillsborough verdict means

Simon Curtis was a match-going Manchester City supporter in the 1980s – a very different era for football fandom stained with tragedy. He explains why Tuesday’s Hillsborough verdict provides justice beyond the 96 fans who tragically lost their lives in April 1989...

The longest judicial inquest in British legal history came to a close on Tuesday, April 26, 2016. Letting the enormity of that fact sink in makes the whole tawdry decades-long exercise in mud-slinging and blame-shifting all the more horrendous.

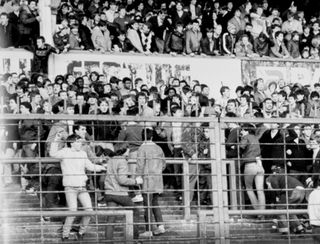

In the aftermath of the jury’s eye-watering verdict in the 27-year-long wait for justice, football fans of a certain age will be reflecting on how it really could have been any one of us, given the callous disregard for safety we as football supporters met every week of our apparently risk-laden lives during a decade of neglect and disrespect.

That is why, for all the occasional jarring moments about wallowing in the past and breeding a grief culture, this decision, dreadfully late though it is, should be seen as a release – first and foremost for the relatives of the families involved in the tragedy, but also a breath of fresh air to anyone who was there in the ‘80s and attempted to follow his or her club through a decade of danger, dirt and decadence.

Very different days

Sporadic trouble-making and segregation-free grounds began to disappear as the warring factions got bigger, more serious and more organised

Contrary to the idea mooted on social media on a daily basis these days, apart from the last five years, following Manchester City hasn’t really been what you might call a bed of roses. In the 1980s, in fact, it was anything but.

As the last dainty notes of Sister Sledge and Boney M faded and the jagged sounds of the ‘80s dawned, the football landscape began to change radically. It would do so again after Hillsborough, spawning the sometimes-anodyne but always-safe environment we watch the game in today.

But first came this jarring, dizzying change for the worse. Much worse.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Sporadic trouble-making and segregation-free grounds began to disappear as the warring factions got bigger, more serious and more organised. This sad development ran hand in hand with the gradual decaying of our league grounds, a new belligerent stance from the police and local authorities, and the growing gloom of a deep-rooted economic depression in the country.

If you were unlucky enough to live in one of England’s major areas of heavy industry, you were reminded on a daily basis of the growing poverty and hopelessness of a country being divided by a Tory government hell-bent on straightening out what it saw as society’s ills: union power, flash strikes, fading steel and coal industries, unemployed hoodlums and football riff-raff. To some of the Eton-educated Tory elite, these oiks were nothing more than rodents scurrying down wet drain pipes.

To enact the changes they wanted, Margaret Thatcher’s government lifted its iron fist without even taking a second to cover it with a velvet glove.

The merciless war on the mining industry, the move to snuff out the great heaving steel foundries, the textile mills and neutering the sodden mass of football fans seemed to be the method Thatcher’s ruling elite had chosen to prove its point. There was no discussion. The scum and the vermin were to be rooted out and disqualified from a society that was about to receive a forced facelift.

Here’s your matchday experience

I witnessed a young policeman approach a father with his seven-year-old son, aggressively snatch a can of coke from the youngster and hit the father when he complained

Going to the football became a nightmare instead of an adventure. To those of us who were living our teenage years in the ‘80s, it remained a kind of psychedelic day out, but the reds and the purples and the oranges were now from cuts and bruises and from staring at the sun through the gigantic hole in the away end roof.

It wasn’t just the simple fear of getting caught by the home mobs that sent a thrill of fear surging up and down your spine as you stepped out of the railway station in Middlesbrough, or Nottingham, or Derby – it was how the police would greet you too. Suddenly there were two enemies and the second one were the very people supposedly there to protect you.

Over a period of time the constabularies of the West Midlands and South Yorkshire began to get a particular name for themselves in this respect. A trip to Villa or Coventry, or either of the Sheffield clubs, was rendered even more hazardous by the heavy-handed approach of the local police forces.

Queuing in the heavy rain outside the very Leppings Lane End that would claim 96 Liverpool fans’ lives, I witnessed a young policeman approach a father with his seven-year-old son, aggressively snatch a can of coke from the youngster and hit the father when he complained that – even if they couldn’t take a soft drink inside with them for fear that little Johnny might turn out to be a malevolent thug – he had plenty of time to finish it in the grime and discomfort of Sheffield Wednesday’s queuing procedures before they got to the turnstiles. For the pasty-faced policeman, there was no discussion to be had.

Unvalued animals

Snapshots like this were of course two a penny. And each week we came back for more.

In this nasty, humourless environment, you would be frisked, pulled and pushed, have meaningless objects confiscated and be made to wait before and after

Every week we returned to run the gauntlet through bleak, wet streets just for the pleasure of being herded violently into over-packed pens with barbed wire and eight-foot fences at the front and sides, rendering the view improbably bleak and the conditions akin to a prisoner of war camp.

In this nasty, humourless environment, you would be frisked, pulled and pushed, have meaningless objects confiscated and be made to wait before and after “the event” wherever they felt it necessary.

At no point did you feel remotely like a customer or a treasured client. At no point did you have any public resource to air your opinion or complain. It was then that the fanzine movement emerged, borne out of a deep-seated frustration at having no voice at all to respond to the government’s whitewash job on all football supporters.

In those desperate times, night games away from home were a particular joy. Being held behind giant wooden gates in the rain while Millwall’s finest arranged themselves in the various alleyways around Cold Blow Lane is a particularly vivid memory, as is being let out into the cold, dark streets around Molineux and the Baseball Ground, Leeds Road and Elland Road.

There were no podiums with boy bands, no kids’ play parks, no shiny superstores to shelter in. Just lines of police, pitch-black streets and the distant scream of sirens and breaking glass.

That fateful day

We didn’t give it a second thought and, until safely back on the coaches south, didn’t realise the horror of what had happened

On the day of the FA Cup semi-final at Hillsborough, those following City through the milk and honey of another dodgy Second Division season, were being ushered in large numbers into the Dickensian squalor of Ewood Park. This was pre-Jack Walker Ewood Park, with its dingy terraces, high metal fences and, on this occasion, dangerously overcrowded side paddocks.

The word “paddock” is in fact a curious one, lost in the mists of another age. These were, as at Goodison Park, Villa Park and indeed Ewood Park, thin pieces of terracing, where the atmosphere was often at its height but the proximity to thousands of others often caused serious haemorrhaging when crowd flow in or out was required.

The situation at Ewood in the sun that spring afternoon could have delivered a disaster just like the one taking place at the very same time on the other side of the Pennines. We didn’t give it a second thought and, until safely back on the coaches south, didn’t realise the horror of what had happened to those Liverpool fans who had gone to cheer on their team in a cup semi-final.

A silent journey home left everyone contemplating how close they had all come to similar disaster in other football venues around the land.

Forewarning

It was April 1981, eight years before the drama became tragedy in the same paddock of the same end of the same football ground

Hillsborough came at the end of a decade chock full of disaster scenarios. The very same ground, the very same end, had been the feature of a serious bottleneck and crushing in the 1981 cup semi-final between Spurs and Wolves.

Manchester City were at Villa Park the same day to play Ipswich Town in the other semi-final. There are moving pictures of the City fans climbing the giant fences at the front of the Holte End to celebrate captain Paul Power’s dramatic winner in extra time.

Skip to 1:40

Spurs fans in the Leppings lane End at Hillsborough were caught in a different mood, subject to horrific crushing that afternoon in Spartan, utterly unsatisfactory conditions. It was April 1981, eight years before the drama became tragedy in the same paddock of the same end of the same football ground. Eight years of inertia and vilification leading to death by asphyxiation at a football stadium for dads and their sons out for the day of their lives.

The inquest of the Hillsborough disaster has finally uncovered the tone and type of police attitude towards football fans in the ‘80s. While the social disintegration being wrought under Thatcher dropped many to new levels of despair, the callousness of the policing at events such as Orgreave and Hillsborough unveiled exactly how the status quo sat at the time.

With Tory club chairmen like David Evans at Luton and the irascible Ken Bates at Chelsea threatening anything from stadium bans to electric fences, public safety and liberty of movement was being undermined to new and disastrous levels. The police fed a willing government the titbits it needed to propel the lie into the public domain.

The public was to be persuaded that it was us that was the problem and boy, were we going to pay for it.

The here and now

In a week’s time, those of us travelling to the Spanish capital for the second leg of the semi-final will face herding tactics by the Spanish police

Supporting Manchester City these days is a different pastime, filled with direct contact with the great and good at the club, customer fidelity points and padded seats.

Modern riches have hoisted City to unforeseen heights, where it is no longer Barnsley we stare at through the railings of the North Stand fences. This week it was Real Madrid instead, with 50,000 glossy flags flying courtesy of the club. All very civilised.

In a week’s time, however, those of us travelling to the Spanish capital for the second leg of the semi-final will face herding tactics by the Spanish police, and conditions in the away sections of the Bernabeu not a million miles from what was happening in South Yorkshire in 1989.

The brutal and unfriendly enforcing of order by the Madrid police in the Champions League group game between the two sides in September 2012 resulted in various smashed heads and whipped legs for crimes such as drinking standing up, and singing in an open space.

The football vista has changed remarkably in England, much of it as a result of the fallout from Hillsborough and the Taylor Report’s subsequent sweeping recommendations. But in the Camp Nou and the Bernabeu, European football’s towering cathedrals, the smell and the look of decay are clear enough to see.

For our €95 tickets in Barcelona, we faced chicken wire, 15-foot netting and bare crumbling concrete as we took the long walk up dark stairwells to a level of the ground teetering just below the Catalan clouds. In Madrid, a simple singalong outside a bar in front of the ground was met with a baton charge and beatings.

Let us hope it doesn’t take another football disaster for the rest of the world to learn how to police its visitors responsibly and treat its guests as fellow human beings. As the ‘80s experiment in brutality proved beyond doubt, the blame can often lie with those who have responsibility bestowed upon them, not the poor souls following their simple passions for the sport of football.

'It was agreed that I’d join Manchester United. So, imagine my surprise when I got off my flight south and heard a Cockney voice saying, "Welcome to Tottenham"': Rangers legend recalls transfer misunderstanding in signing for Spurs

‘I joined Salford, initially on loan, from Derby U21s – I may be the only manager who’s ever gone out on loan! I loved the history and where the club came from’: Football League boss recalls bizarre managerial move in 2021