What the heck happened to Alaves after 2001?

UEFA Cup finalists against Liverpool 15 years ago, they’re only just making their way back into La Liga again after years yo-yoing in the lower-league wilderness. Robert O'Connor explains what happened…

When Delfi Geli hoisted himself into the Dortmund sky at a little after 11pm on May 16, 2001, all was well in the world of Deportivo Alaves.

They’d just completed a third straight season in La Liga, equalling the club record for consecutive seasons spent in the top flight, and having qualified for a debut season in Europe, had thrilled their way to the UEFA Cup final to face European royalty in Liverpool.

A remarkable game had finished 4-4 after normal time and was minutes away from being settled by penalties. The Westfalenstadion crackled with nervous energy as Geli rose to meet Gary McAllister’s free-kick, and all was well.

Not-so-great expectations

In 1990 they were promoted, and again in 1995 and 1998, sealing sixth place in just their second season in La Liga to claim an unprecedented European spot

Alaves are a modest club. Hailing from Vitoria in the Basque Country, their quaint Estadio Mendizorroza holds just shy of 20,000 – but these aren’t the sort of crowds that have watched the side throughout most of its 95-year history spent flitting between Spain’s second and third tiers.

This was especially true during the period of 1986-90, when the side known somewhat erroneously as El Glorioso slipped into the fourth division. In 1990 they were promoted, and again in 1995 and 1998, sealing sixth place in just their second season in La Liga to claim an unprecedented European spot.

Alaves enjoyed 11 years as one of Europe’s freest and most buoyant clubs.

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

One-time Barcelona player Delfi Geli had been deployed as the left-wing-back from the start in the 2001 final in Dortmund, but had been moved deeper after 22 minutes as Alaves reshuffled in response to falling 2-0 down to goals from Markus Babbel and Steven Gerrard.

Thereafter his performance had been solid, having largely kept a lid on Michael Owen and Emile Heskey at a time when those names still meant something in European football.

At 4-4, and with time slipping away, McAllister sent his free-kick spinning into the box. There was a clear call from Argentine Martin Herrera in the Alaves goal but Geli didn’t heed it, climbing to flick past his stranded goalkeeper for that most agonising of agonies; a golden own goal, in a European final – the last that his side was likely to see.

Reality bites

It would be needlessly dramatic to say that Alaves were never the same again after that goal. Their candle had burned so briefly after generations spent dimly lit that its dousing came as something to be expected rather than explained.

Geli’s own goal, which gifted Liverpool the UEFA Cup in May 2001, marked not just the end of something special but the beginning of a genuinely torrid spell

But Geli’s own goal, which gifted Liverpool the UEFA Cup in May 2001, marked not just the end of something special but the beginning of a genuinely torrid spell in the history of this intrepid little outfit.

Two weeks after the heartbreak in Dortmund, El Glorioso were further put in their place by the new La Liga champions: Real Madrid cruised to the title with a 5-0 win at the Bernabeu as Luis Figo reminded the world why los Blancos had moved heaven and Earth to make him the most expensive footballer on the planet.

It was utterly sobering for Europe’s new nearly men. Meanwhile, Alaves’s own talisman, 22-goal marksman Javi Moreno, was pipped to the Pichichi top goalscorer prize by the hosts’ Raul (he eventually finished third behind Rivaldo), as natural order quickly restored itself.

Picked apart

Moreno was first to go, snapped up eagerly by Milan for £12 million after he capped a fine domestic season with two goals in two minutes in Dortmund

Then came the inevitable dismantling of the team. Moreno was first to go, snapped up eagerly by Milan for £12 million after he capped a fine domestic season with two goals in two minutes in Dortmund to wipe out Liverpool’s 3-1 lead. The move was an abject failure.

Two goals in 16 appearances for Milan led to a sharp exit, first to Atletico Madrid and then to Bolton and Zaragoza. None of the moves worked out, and it would be 2005/06 before Moreno – briefly one of the hottest strikers in Europe – was to hit double figures again in a season, by which time he was back playing in the third division with Cordoba.

Cosmin Contra, the great Romanian full-back who had starred in the final, also left for the San Siro before he too was deemed surplus, heading for Atletico and then the lower reaches of the Premier League with West Brom. The Serbian Ivan Tomic returned to Roma from his loan spell, while goalkeeper Herrera soon left for a disastrous season at Fulham.

By 2003, seven of the 11 that started the 2001 final were gone, as Alaves dropped out of La Liga after a five-year stay.

Years in the wilderness

Relegation followed relegation: in 2009 they went back down to the third tier for the first time in 15 years.

Moreno, Contra, Tomic and the rest were emblematic of what so often happens when serendipity invites sudden success into a previously dormant club.

Alaves flourished with the right blend, under the right manager in Jose Manuel Esnal, and all at the right time. Outside of those conditions the formula floundered, and so too did the players who had made it all work. There was something necessarily brief about Alaves and the great side of 2000/01 that took Europe by storm, who scored 31 goals en route to the final and another four when they got there.

They returned briefly to the top flight in 2005/06 but by then there had been an almost 100% turnover of personnel on and off the pitch, and relegation followed relegation. In 2009 they went back down to the third tier for the first time in 15 years.

They’ve since yo-yoed between the two tiers of the Segunda Division, where they spent most of their formative years playing before modest crowds. This season, however, they’ve made it back to the top flight, where Real Madrid & Co. await them once more. Many things have changed.

Slide away

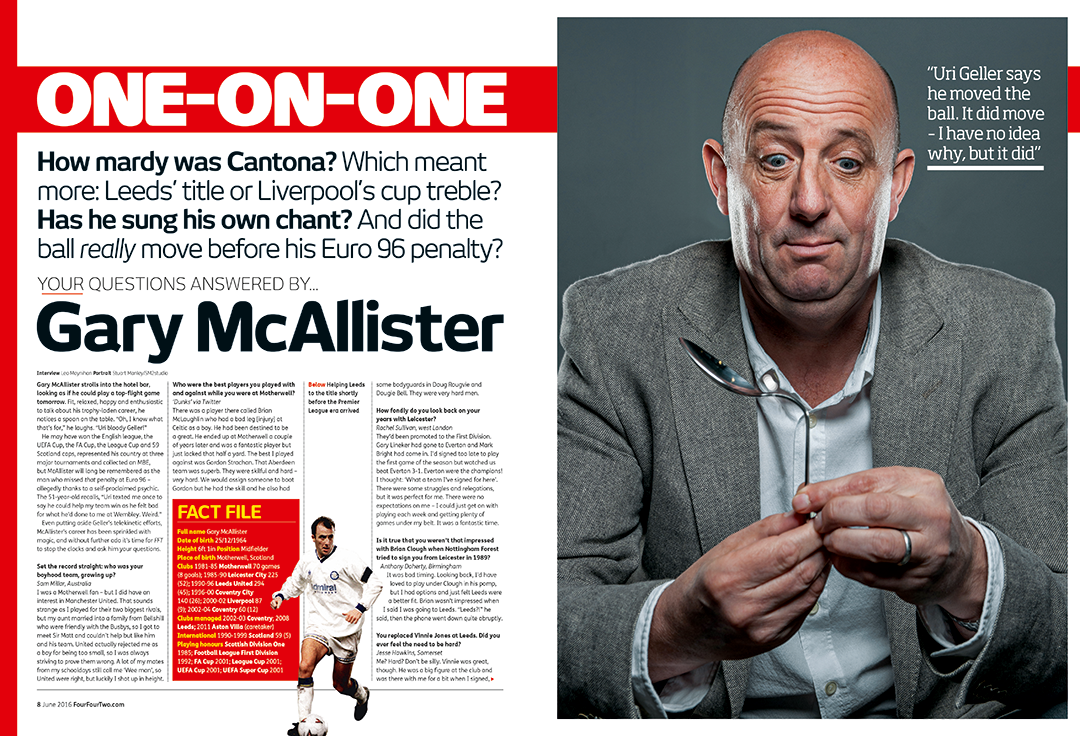

Gary McAllister said in the aftermath of the 2001 final, one of the greatest the UEFA Cup has seen, that he had been pleased for the Alaves game to have come late in his career. It gave him a chance to savour the experience in a way that young players don’t so much. “As a young man games like this tend to pass you by,” he said wistfully, years later.

How Alaves must feel similarly. For 116 minutes in Dortmund they stood shoulder to shoulder with kings, before receding back into the shadows almost as quickly as they’d risen.