What separates Rooney, Kane and Vardy the most has nothing to do with ability

Could self-belief actually lead to better technique? Alex Hess explains why mentality and ability are not as independent as you might think...

Here's a question: Other than getting picked for the latest England squad, what links the performances of Jamie Vardy, Wayne Rooney and Harry Kane so far this season?

Wayne Rooney's attempts at scoring have been much like the kids’ in American Pie: plenty of earnest toiling for an awful lot of undignified failure

If your gut response is 'absolutely nothing', then you're closer to the answer that you might think. After all, Vardy has been imperious in front of goal in recent weeks, while Wayne Rooney's attempts at scoring have been much like the kids’ in American Pie: plenty of earnest toiling for an awful lot of undignified failure. Harry Kane, meanwhile, has oscillated between both extremes with scant regard for the middle ground, an eight-match goalless spell sandwiched neatly between last season’s gloriously lethal form and the six goals notched in his last four outings.

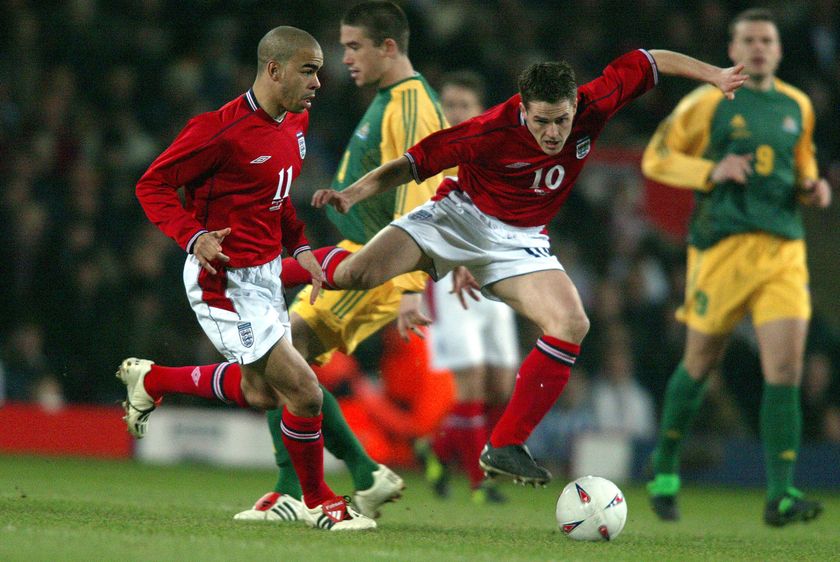

Which is all a rather roundabout way of saying that the answer to the initial question is, quite simply, confidence. Or at least that’s the way it seems looking from the outside in. Rooney, whose footballing ability has enabled him to spend the last decade-and-a-half as a mainstay of elite-level professional sport, has played the last few months as though wearing invisible clown shoes.

Vardy, whose pre-Leicester CV consists of a £30-a-week stint at Stockbridge Park Steels before heading on to the bright lights of Halifax and Fleetwood, has conversely spent the campaign laser-beaming balls into nets, creeping towards prestigious modern-era goalscoring records and prompting comparisons with Gabriel Batistuta at his peak.

Taken as a pair, Rooney and Vardy currently provide a living, breathing demonstration of the colossal power that confidence, sport’s great intangible, holds over performance. Kane, whose puppyish rise to stardom has painted a portrait of the archetypal ‘confidence player’, completes the set.

Technical improvements

One of the most remarkable aspects of Kane and Vardy’s form is that their actual technique seems to have been elevated to new heights by an upturn in self-belief

You needn’t look far to find a footballer referencing the C-word as the magic ingredient in their best form. A personal favourite is Frank Lampard’s retelling of the moment in 2004 when Jose Mourinho approached him in the shower (“while I was cleaning my balls”) and offhandedly informed him he was the best player in the world: “From that moment the extra confidence was in me… I went out a different player.” Simple lark, management.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Sure enough, Vardy recently described himself as “oozing confidence”. Kane has spoken of last season’s bewildering goalscoring run as the product of “playing with no fear”. These may sound like run-of-the-mill interview phrases but they are also an insight into the mind of an elite sportsman – and possibly into their body, too.

One of the most remarkable aspects of Kane and Vardy’s form is that their actual technique seems to have been elevated to new heights by an upturn in self-belief. Think back, for instance, to Kane’s second goal in Spurs’ 5-3 win over Chelsea last year, when he received a pass on his left instep, rolled silkily away from his marker and slotted home with his right, all in one crisp movement. Or the way Vardy, charging goalwards at full speed, was able to kill dead a looping long pass dropping over his shoulder – a notoriously difficult technique – in drawing the foul to win a penalty against Watford last weekend.

Conventionally, we conceive of ability and mentality as two completely separate entities. But watching these previously unremarkable players suddenly imbued with confidence and able to summon moments of genuine technical majesty, the distinction starts to seem rather hazy.

Relaxed muscles

Dan Abrahams, sports psychologist and author of Soccer Tough: Simple Psychology Techniques to Improve Your Game, is an ardent assailant of the conventional wisdom. “I don’t think this model [of talent and mentality existing separately] could be further from the truth,” he says. “A player’s ability level and their mental state are completely integrated. Science has shown us the link between mind and body – and if that sounds a bit airy fairy, then put it like this: If I’m lacking confidence, I’m going to be indecisive, and indecision gives my muscles less time to coordinate for moments of skill.

“Similarly, playing with confidence – which also means playing with certainty and freedom – will help create a more relaxed muscular state where exceptional technique is far more possible.”

So the intangible suddenly becomes very tangible indeed. And if technique and mentality are not, as Abrahams argues, as disparate as we might think, then the idea that Vardy and Kane are simply limited players enjoying perishable hot streaks suddenly seems highly dubious, too.

The Wright mindset

The most pertinent example is Ian Wright, the man as good an advert for the liberating effects of self-belief as any footballer has ever been

Perhaps, as evidenced by Kane’s continued goalscoring in the face of all the ‘one-season wonder' doubters, confidence isn’t a finite resource at all. Perhaps the regression to the mean, which many presume will befall Vardy sooner or later, might not be such a certainty.

There are countless examples of centre-forwards whose output has appeared innately entwined with a sense of unshackled exuberance. The Robbie Fowler of the mid-1990s springs to mind, likewise Fernando Torres after initially arriving in England. The chronic downturn in form suffered by both, once that exuberance deserted them, hammers home the point.

But the most pertinent example is Ian Wright, the man as good an advert for the liberating effects of self-belief as any footballer has ever been. Wright spent years toiling away in lower- and non-league football before finally hitting the big time in his late-20s and never looking back. Remind you of anyone?

“Every player has periods of being ‘in the zone’,” says Phil Johnson, a clinical sports psychologist who has worked for a number of top clubs across Europe. “It comes when they are playing with no distractions. They also tend to be playing instinctively, without any conscious sense of analysis.

“The key word is ‘momentum’. If you think that your goal run is going to end, it could become a self-fulfilling prophecy. From a psychologist’s point of view there’s no reason that you can’t stay in the zone, but to do so you need to stay relaxed, stay calm – you need to have fun.”

It's all in the head

The hazing of the line between ability and mentality seems to offers some crystal-clear insight into the recent fates that have befallen England’s current forwards

Perhaps, then, the crucial element is not the C-word, but the F-word. After all, how fun must it be right now to be spearheading the forward line of a Leicester side who have spent the past four months honking the noses of the sceptics and pole-vaulting themselves to a mere point behind the league leaders? Similarly, how fun must it be to be playing the same role for the division’s most zestful young tyros at Tottenham, the club finally deemed to have overcome its longstanding fragility whose fans take every chance to bellow proudly the fact that you’re “one of their own”?

On the flip side, the enjoyment to be had at the tip of Manchester United’s plodding attack right now is surely minimal. Not least when fixtures at Old Trafford have begun to be soundtracked by the despairing wails of dissatisfied home fans, and the sudden presence beside you of a zippy, fearless young forward acting as a kind of Banquo’s ghost, a macabre reminder of all of your failings.

RECOMMENDED Wayne Rooney: Just what happened to that boy from Euro 2004?

Of course, when good fun and good form are paired together as simply as that, the chicken-and-egg question looms large, and as such a straightforward explanatory model seems elusive. But there’s nothing necessarily wrong with a little haziness – after all, the hazing of the line between ability and mentality seems to offers some crystal-clear insight into the recent fates that have befallen England’s current forwards.

Certainly, under this light, the old adage that ‘form is temporary, class is permanent’, appears to be something of a reductive red herring. Which is splendid news for two-thirds of England’s strikeforce – but rather less encouraging for the other one.