What's next for Pep? Another year at Bayern – and then a leap into the unknown

Bayern Munich's big cheese has already pledged to serve for another year at the Allianz Arena, but it's a big one to determine what comes next, writes Alex Hess...

There is such a thing as being too good for your own good. When, for example, a 21-year-old Nasir Jones released his debut album Illmatic in 1994, he had little idea of the trouble his brilliance would cause him down the line. Illmatic may have been a work of unmatchable genius but, unfortunately for Nas, each and every one of his subsequent efforts was held up in comparison, each and every one inevitably deemed a let-down by association. Harsh? Maybe. But such is the price of greatness.

Like poor old Nas, Bayern Munich are currently suffering from having skewed their own standards so far upwards that anything bar the very greatest success is deemed a failure.

Last season, following the arrival of skinny-tied uber coach Pep Guardiola, Bayern won a domestic double, wrapping up the league before spring had barely sprung and breaking almost every record under the sun en route to doing so (so many, in fact, as to demand an entire Wikipedia entry unto themselves).

But underneath all of that, a small asterisk will always remain thanks to Bayern’s failure in the Champions League (‘failure’ here defined as semi-final defeat to eventual winners Real Madrid).

"Only the treble will suffice"

This season, then – with another year’s schooling in the finer arts of football, another year for Guardiola to galvanise his squad, and another attacking luminary plucked from the low-hanging branches of their most immediate German rivals – the onus was on Bayern Munich to go one better.

In the event, they’ve managed to go one worse. The Bavarians have retained their league title but not the cup, and, worst of all, have only managed to tread water in Europe.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Last year’s comprehensive and humiliating demolition at the hands of a Spanish giant was slightly less comprehensive and slightly less humiliating this time around, but the net effect has been much the same: when the most vital occasion came along, Bayern failed to live up to their billing.

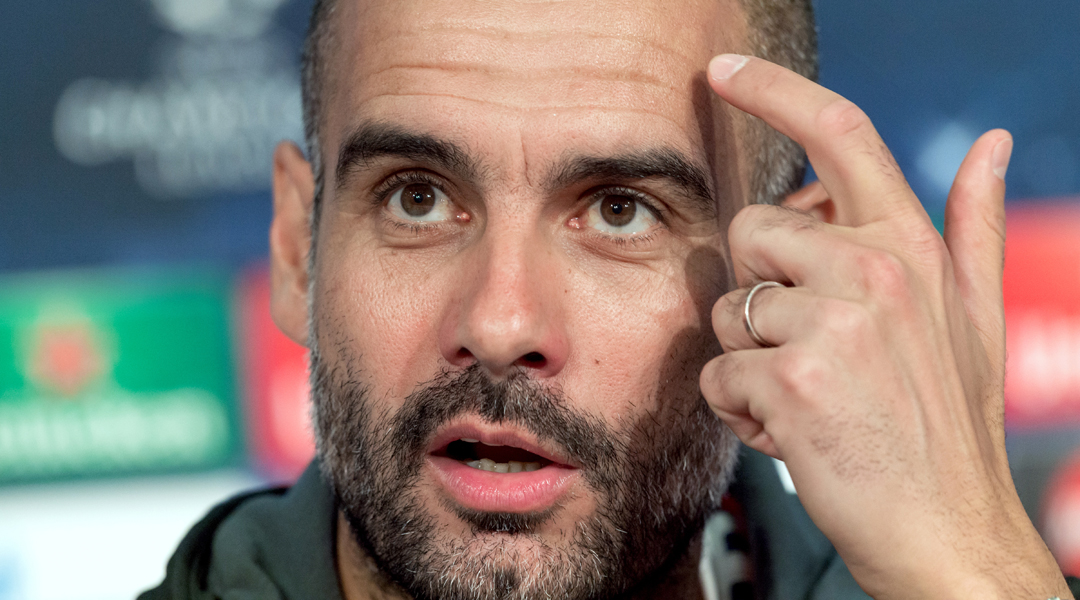

Guardiola does not need telling. "I know that winning the Bundesliga title will not be enough," were his words back in April. "I also know that winning the DFB-Pokal on top of that will not be enough. This is Bayern Munich. Only the treble will suffice."

There is a certain irony at work here, and not one that the hordes of Bavarians still picking themselves up from their latest European exit are likely to laugh too hard at.

Having been so thoroughly magnificent in the league (and so thoroughly ruthless in their close-season recruitment), Bayern have essentially, with that trophy all but a given, created a situation where their season’s success will be judged almost squarely on their performance in the Champions League.

And the Champions League is a far more erratic barometer of a team than the 38-game league season at which they’ve so excelled. Over a league season, the odd careless loss gets diluted. In a knockout tournament it can be decisive.

Unfortunately for Pep – and ominously for Bayern – his tenure has taken the club’s trophy count down from the three gleaned in Jupp Heynckes’ final season to two last year, and now to one. And while tallying silverware is no real measure of long-term progress, it does begin to throw the Spaniard’s reign into a light that flatters him rather less than the general air of reverence afforded to him throughout the football world.

Back at Bayern

The question now, then, is how exactly the club go about ensuring that next season’s portfolio encompasses European as well as domestic honours. Guardiola, having twice guided Barcelona to this double triumph, should be aware of what is required to bring home the bacon on two fronts.

Nor is he the only person at Bayern to hold such knowledge. And those who remember back far enough will be well aware of how difficult a balancing act it is. When the club won three consecutive European Cups in the mid-70s, their domestic form suffered. In the last of those seasons, the club finished third in the league.

It's the triple-header of wins that immediately preceded that – that of the Johan Cruyff-led Ajax in the 70s, from whom many of Pep's principles spring – that offers history’s best blueprint of two-pronged dominance. That side managed to complement three European successes with two Eredivisie titles. In the same decade Liverpool hit similar heights, garnering two leagues and two European Cups in three seasons.

The difference between these sides and the current Bayern Munich one may only be the smallest of details – like a goalkeeper throwing the ball out to an under-pressure left-back as the Camp Nou’s clock ticked into the 77th minute – but it also may be a touch of fine-tuning.

German sports magazine Kicker responded to Tuesday’s loss by calling for less tactical experimentation from Guardiola, and they could well have a point. While the constant positional shuffling that the Catalan imposes on his sides oozes modernity, sometimes familiarity can breed contentment – and especially so at a club where the players haven’t spent their youths being intensely schooled in the art of versatility.

Yet such a demand is to miss the point of his methods. It’s precisely this shifting, tweaking and evolving, this constant outrunning of stasis, which defines a Guardiola team. One of the most awe-inspiring traits of his globetrotting Barca side was the feats of tactical contortionism they performed on an almost weekly basis.

Certainly, Bayern's squad could use some rejuvenating. Bastian Schweinsteiger, Franck Ribery, Arjen Robben, Xabi Alonso and Philipp Lahm are all starting players whose 30th birthdays have come and gone.

And while Guardiola can legitimately claim miserable luck with injuries this term, having to face Barcelona without Robben, Ribery or David Alaba, there’s a few who would say relying on Robben not to get injured is like relying on Larry David not to worry about the minutia of daily life – you can hope for the best, but it’s going to happen sooner or later. To this end, some bolstering is needed in the creative department, which could equally be to say that Mario Götze needs to finally live up to his €37 million price tag.

Next summer's scuffle

Guardiola prefaced Tuesday’s game with an attempted swat at the constant buzz of rumour that accompanies his coaching career. "Next season I will be here, that’s all there is to it," he declared. But what if next season fails, once again, to edge the club closer to reclaiming the trophy it won under Heynckes? If you’re to believe what you read, Guardiola chooses his projects using the Stanley Kubrick blueprint: with near-mythical care and with no qualms whatsoever about biding his time. The problem for a coach of his stature is that the small contingent of top European clubs capable of competing at the highest level is becoming evermore rigidly defined. Unless he feels the need to drop down a level, his list of prospective employers is not extensive.

Paris Saint-Germain, for example, having whittled their domestic league down to a one-horse race, would present the same problem as Bayern. La Liga offers only two clubs capable of competing, both of which we can presume, for the time being anyway, are out of bounds.

Which leaves Italy – a revitalised Juventus would seem as plausible an option as any – and England. It’s little secret that Manchester City, having already transplanted a good deal of Barcelona’s backroom team into the Etihad’s corridors of power, have been batting their eyelids at Guardiola for some time.

City, though, in its current incarnation, have been built from the top down rather than the bottom up, and one wonders how keenly Pep, known to place such emphasis on structural setup, would take to that.

In this regard, the respective projects at Old Trafford and the Emirates Stadium might appeal rather more, despite each clubs’ current reduced standing. But that’s not to say either would necessarily be an option.

And of course, any of the three would almost mean Pep doing something that onlookers the world over would feast their eyes at but would make his own stomach sink at the mere prospect: facing Mourinho.

Having both come out of their last rendezvous looking like they’d taken a long drink from the wrong holy grail, one wonders if either could quite be bothered with going through it all again.

Boxed in

Perhaps the only guarantee is that he is unlikely to rush into anything. At the end of it all – and herein lies the paradox for the most outwardly obsessive coach in modern football – Guardiola doesn't seem to draw his own sustenance from the sport in the manner of many of his peers. Mourinho, for example, spends his years leapfrogging from superclub to superclub, waging wars with a different nation’s media and picking fights with whichever anodyne manager happens to wander obligingly into his crosshairs.

Sir Alex Ferguson famously postponed his retirement for 12 years, openly terrified of just how he’d cope ("I've been on the train for so long that when I get off it, I'm scared my body will shut down," were his words). Wenger’s Totteridge home has been specially fitted with a satellite dish to ensure that, once he arrives home from a hard day’s football coaching, football is beamed in from all corners of the globe.

Pep, meanwhile, followed his departure from Barcelona by taking a year off to hang around in Greenwich Village, sipping espressos, playing with his kids and befriending the odd chess champion.

Rather than a shortage of adrenaline that only football can provide, Guardiola’s biggest problem would likely be that, with the continent’s elite clubs slowly boxing themselves off from the rest, he faces a paucity of options. But as he well knows, sometimes you can be too good for your own good.