When Alex Ferguson got sacked at St Mirren: 40 years on from the job that made him

On this day in 1978, Fergie was told to clear his desk at Love Street. He lost his fight in court, with an industrial tribunal ruling he had "neither by experience nor talent, any managerial ability at all". Showed them, didn't he?

In 1976, a fiery young manager named Alex Ferguson took Scottish second division side St Mirren on a three-week tour to the Caribbean. The trip had only been possible because the former chairman, Harold Currie, had contacts in the whisky export trade. Although Ferguson had a reputation as a troublemaker, the tour started off peacefully. But then they arrived in Guyana.

Guyana were gearing up for a crucial World Cup qualifier and, unlike St Mirren’s previous opponents, they did not treat the friendly as a friendly. When the game started, their big centre-back began to kick young striker Robert Torrance. On the touchline, Ferguson complained to the referee, to no avail. When the defender hacked down Torrance again just after half-time, Ferguson lost it.

“That’s it,” Ferguson told his assistant David Provan. “I’m going on.”

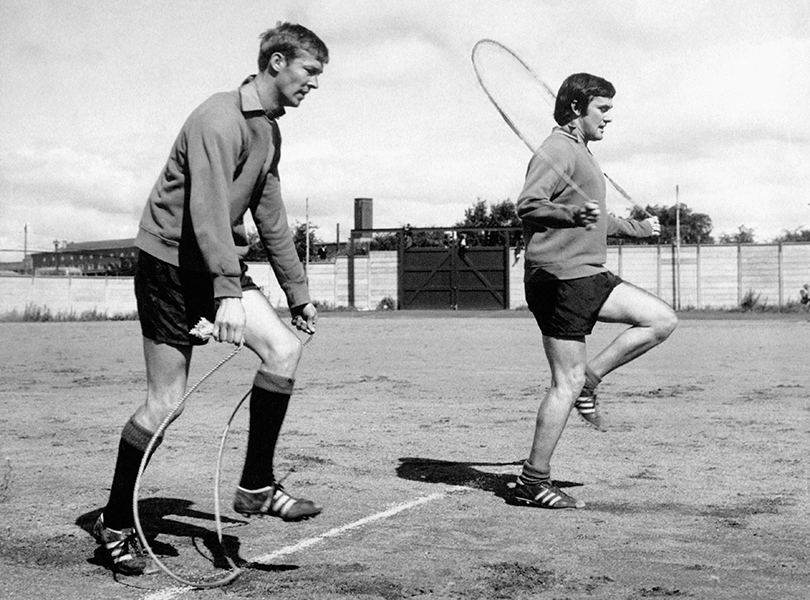

Throughout the tour, Ferguson and Provan had dressed up as subs just for fun, so the manager was ready to go on. He had retired two years earlier, having played in Scotland’s top two divisions as a sharp-elbowed striker. Now Provan was trying to dissuade him, but Ferguson was fired up. “That big bastard is taking liberties,” he said.

When the next cross came into the box, Ferguson “exacted a bit of revenge” on the defender. They continued to battle until Ferguson, in his own words, “nailed” his opponent “perfectly”. As the defender rolled around in pain, Ferguson got sent off.

“Don’t ever let anyone know about this sending-off,” Ferguson told his players afterwards. Nobody did. They knew that if you said nothing, you’d survive. Tell, and you’d enter the Black Book.

Frightening

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

The Black Book held the names of those doomed souls who had irked Ferguson. Tardiness was a typical offence, though anything could set him off. When he'd arrived at St Mirren two years earlier, the local Paisley Daily Express had sent a photographer to take a team photo. When it appeared in print, Ferguson saw that the captain, Ian Reid, had made rabbit ears behind him. Ferguson called Reid into his office.

“If I’m looking for a captain, I’m looking for maturity,” Ferguson said. “That was a childish schoolboy trick. You have to go.”

People at Manchester United feared Ferguson for his temper. He used to be far worse. As a player he had berated centre-backs, referees and even team-mates, once marching the length of the pitch to confront a player on his team over a misplaced pass. It was a testimonial match. When Ferguson retired, he took charge of East Stirlingshire. “I’d never been afraid of anyone before,” said striker Bobby McCulley, “but he was a frightening bastard from the start.”

Four months later, Ferguson joined St Mirren having been recommended by Willie Cunningham, the outgoing manager who had coached him at Dunfermline and Falkirk. At 32, Ferguson had little to lean on beyond his playing career, a natural decisiveness and burning determination. The day he arrived, he told himself: “I’m not going to fail here.”

Exiled from Love Street

St Mirren had just finished 11th in the second division. Their stadium, Love Street, held 25,000 but usually drew 3,000. The players had part-time contracts worth £12 a week. The coaching staff were a band of four: assistant manager Provan, a reserve team coach, physio and part-time kit manager. Day-to-day operations were in the hands of the groundsman. “Everything about the club was run down,” Ferguson wrote.

Worse, St Mirren were slipping down the table at the worst possible time: the following season, the top two divisions would split into three. The top six teams would join the new second division and the rest would slide down into the third. Ferguson knew he had little time, and even less to work with. When he first looked at his 35 players, he decided that most of them would have to go.

He immediately installed discipline. When a player named John Mowat defied his instructions, he followed Reid into the Black Book. One player was reprimanded for driving to an away game instead of taking the team bus. Another said he’d miss training because he was taking his girlfriend to a pop concert. Ferguson told him not to come back. “I just wanted to make it very clear to all the players that I didn't want to be messed about with,” Ferguson wrote. “They got the message.”

Trouble at Fergie’s

St Mirren were soon climbing the table. Besides filling the team with his Glaswegian street-fighting spirit, Ferguson created the blueprint that he would later copy at Aberdeen and United. He drilled in a high-octane style of attacking football and built a productive local scouting network. At one point, St Mirren won eight games in a row, prompting Ferguson to proclaim that they wouldn't lose again that season. They duly lost two of their last five, yet finished sixth; enough to secure a place in the new second division.

Ahead of his first full season, Ferguson targeted promotion. Complicating matters was his second job: hired on a part-time contract, he'd opened a pub in Glasgow to make ends meet. While ‘Fergie’s’ attracted all kinds of people, most were rugged dockers who liked a scrap. More than once, Ferguson had to break up brawls, coming home with a split head or a black eye.

“You weren't likely to find Sylvester Stallone, Bruce Willis or Arnold Schwarzenegger in my place.” Ferguson wrote. “Though you might have encountered the odd costumer who, single-handed, could have put the three of them to flight.”

The two jobs forced Ferguson to start his day at Love Street, then leave at 11am to run the pub until 2.30pm. Then he’d return to Love Street to take training, then return to the pub for the night shift, then go home. He hardly had time to see his young family. As for St Mirren, they started well before eventually finishing sixth. Ferguson would later write that, had he been able to focus solely on football, the team might have fared better.

Boosting the church choir

Not that anyone could call Ferguson inefficient. As St Mirren geared up for another shot at the big time, he took charge of everything. He bought cleaning material and ordered pies for matchdays. He started a club newspaper called The Saint. When he saw that fans were jumping the fences on matchdays, he lowered the roof so that nobody could clear the turnstiles. “Nobody at the club worked harder than he did,” chairman Willie Todd, who had replaced Currie, wrote in the Guardian.

The bond Ferguson forged with the fans served the team. Besides founding The Saint, he’d play bingo twice a month at the St Mirren Social Club. When, before the next season, Ferguson wanted to sign Dundee United centre-back Jackie Copland without a penny in the bank, he was granted a £14,000 loan by the St Mirren Supporters’ Club which helped him pull off the deal.

By the third season, St Mirren had become more professional in every aspect. On the pitch they had a team that mirrored Ferguson: young, exciting and brash. Yet one aspect kept annoying Ferguson. The crowds, he’d write, were “barely larger than a church choir”.

St Mirren were based in Paisley, a town hit by rising unemployment in the shadow of Glasgow. Each weekend, people would take the bus to Glasgow to watch Celtic and Rangers. Ferguson felt the town had an inferiority complex. So one day, club electrician Freddie Douglas strapped a loudspeaker to the roof of a van in which Ferguson toured Paisley, microphone in hand, talking up his team and encouraging people to turn up at Love Street.

The stunt seemed to work. Attendances rose to an average of about 10,000 and, in that 1976/77 campaign, the big games drew nearly double that. By January, St Mirren were fighting for the title.

The Waterloo Bar

As St Mirren marched towards the top flight, Ferguson fought anything that could derail their form. Some of the things he regretted. Once, he hauled young midfielder Billy Stark off the pitch after seven minutes. “I was hot-headed, very passionate about my job,” Ferguson wrote.

What he didn't regret was his stance on boozing. Like at Aberdeen and United, he had a network of informants who could bust players out on the lash. At Aberdeen, the midfielder Gordon Strachan would once see him drive past his house on Friday night to check that his car was at home. “He had an omnipresence,” Billy Stark told Ferguson biographer Patrick Barclay. “You always felt you were being watched by him, at or around the club.”

So when Ferguson got a call from a friend after a Scottish Cup defeat at Motherwell, he was not pleased. The day before the match, Ferguson was told, young striker Frank McGarvey had been seen drunk in the Waterloo Bar in Glasgow. Though McGarvey had just earned a call to Scotland’s under-21 side, Ferguson told him he’d been withdrawn, that he was finished in football, and that he never wanted to see him again. Only a week later, when McGarvey approached Ferguson and his wife Cathy at a supporters’ event, begging for mercy, did Ferguson relent.

Forgiveness was a rarity, however. Before a game at home to Partick Thistle, Ferguson’s brother Martin told him that some players had again visited the Waterloo – and they'd also moaned about their bonuses. After St Mirren won 1-0, Ferguson gathered the culprits in one end of the dressing room and let rip. His anger grew. Finally, he grabbed a Coca-Cola bottle and smashed it against the wall above the players. None of them moved.

By the time they went home, Ferguson had forced the squad to sign an agreement that they would never again enter the Waterloo. The alternative was to train every Saturday night. The players may not have liked it, but the measure worked. St Mirren won the league.

Fergie vs Todd

The promotion was Ferguson’s first big success as a manager. He was now planning to take St Mirren into full-time football and challenge the elite. When Aberdeen approached him that summer, in 1977, he turned them down.

But he would regret it. Shortly after he'd joined St Mirren, the club was bought by Todd, who Ferguson said “didn’t know much about football”. Whatever was true, Todd thought he did, and they began to argue. Cliques in the boardroom muddied the waters; some backed Ferguson, others didn’t. Distracted by infighting, Ferguson struggled to keep St Mirren above the drop.

As the end of the season neared, the communication between Ferguson and Todd broke down. The final few months were unpleasant for both. Ferguson thought he could take on his own chairman, a move he later described as naive. St Mirren scraped to 10th, six points above the relegation zone. When Aberdeen contacted Ferguson again in May, he wanted out.

What worried him was that St Mirren could sue him for breach of contract, and so he delayed his decision. In late May, Todd called him into his office and presented a list of 15 instances in which Ferguson had broken his contract. Dismissing them as farcical, Ferguson started to laugh. Todd would later say that the real problem had been that Fergie had told his staff he was going to Aberdeen, and that he'd asked at least one player to come with him. “The issue was St Mirren being destabilised because the manager wanted to leave,” Todd wrote.

In any case, Ferguson cleared his desk. Bitter over the fallout, he sued Todd for wrongful dismissal. Todd won the case. The industrial tribunal ruling described Ferguson as “possessing neither by experience nor talent any managerial ability at all”.

By that time, Ferguson had joined Aberdeen, with whom he would crush the Old Firm duopoly and win the 1983 Cup Winners’ Cup final against Real Madrid. He joined United in 1986.

As for Todd, he would go down as the only man who got rid of Ferguson. “It was a simple case of myself, as chairman, doing what was best for the football club,” Todd wrote. “I had no option but to sack him in the end.”