When the NASL rocked America: Elton John, Jagger and the age of excitement

Sensible business models? Pah! Two decades before MLS finally did it properly, soccer Stateside was run by rock stars, movie moguls and music execs. Oh, but it was fun...

The scene is a familiar one. The football club owner takes position on the touchline, a microphone thrust into his face and a barrage of questions aimed in his direction for the benefit of a live television audience. The owner bats back his answers with calm professionalism and no small amount of platitudes; how he’s “very excited” for the team, how the club is “growing and growing”, how “fantastic” the whole set-up is.

But this is no ordinary owner and this is no ordinary team. He is neither self-made local businessman nor a Russian oligarch – and this is no interchangeable out-of-town municipal stadium.

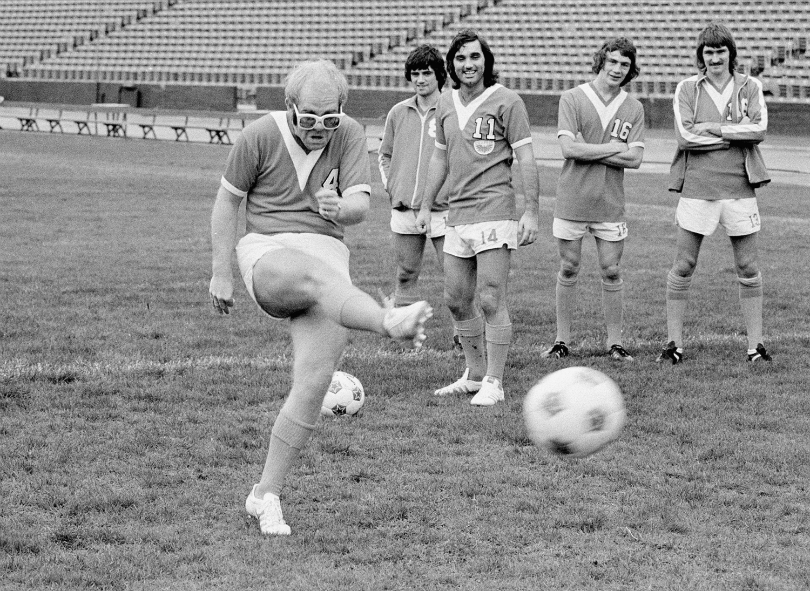

It’s the summer of 1977 and we’re at the Coliseum in Los Angeles, the venue that will, in seven years’ time, host the Olympics. While the TV interviewer asks his questions, a motorcycle display team entertains the half-time crowd behind him. Of most note is the flamboyant attire of the club owner: flat cap, mirrored shades, orange-and-black striped jacket. He looks like a pop star – because he is a pop star. His name is Elton John.

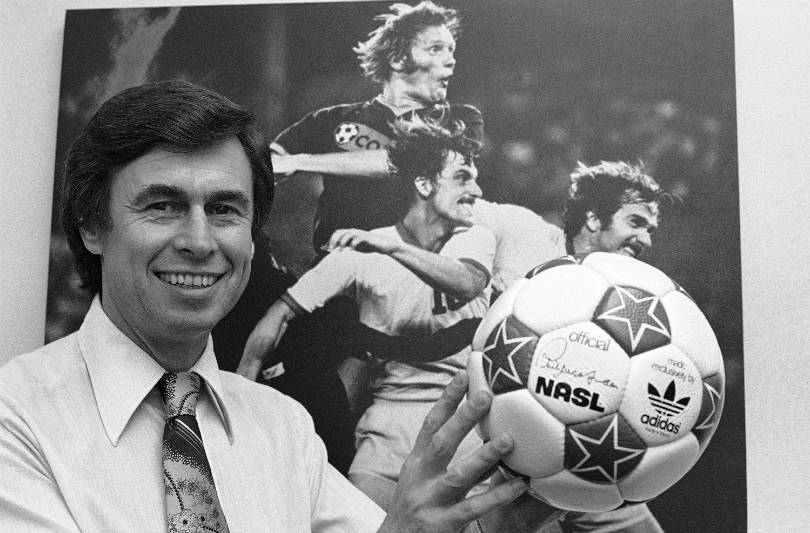

The musician – pictured left performing at LA’s Dodger Stadium – had a two-year tenure as a co-owner of Los Angeles Aztecs in the late ’70s, and this was no anomaly. Similarly, the rumoured involvement of Spice Girls/S Club 7 manager Simon Fuller in David Beckham’s imminent MLS franchise purchase is far from the first union between the music industry and US soccer. It continues a mutual fascination that studded the North American Soccer League’s comparatively brief life, a time when rock stars and music execs ploughed their royalties into teams across the country, from LA to New York, via Philadelphia, Colorado and Oakland.

New York Cosmos: Nesuhi and Ahmet Ertegun (Atlantic Records)

“Somebody from Warner told me that the brothers were very upset because we were a Turkish club without a Turkish player. So I gave way and signed the goalkeeper Erol Yasin. But he wasn’t the best, so he didn’t play."

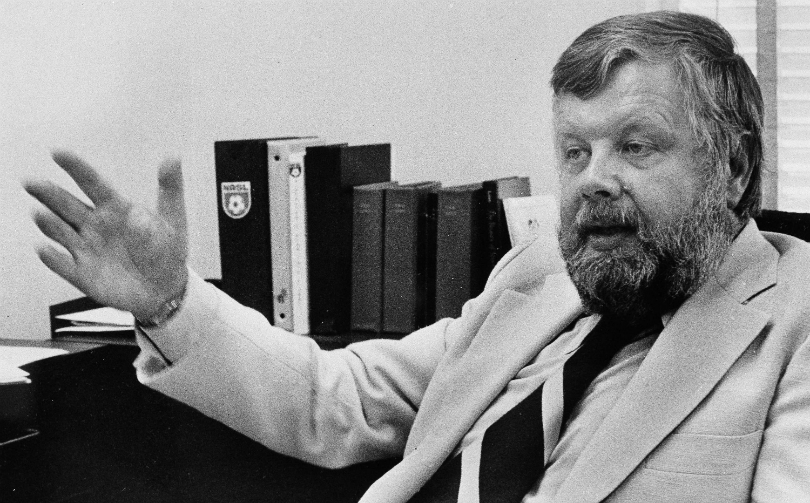

The NASL’s most celebrated team, the New York Cosmos, had its roots in the music business. In the late 1960s, a pair of Brits – former footballer Phil Woosnam and ex-Daily Express sportswriter Clive Toye – were gallantly trying to build their embryonic football league and keen for someone with deep pockets to take on a New York franchise.

Having already approached – and been turned down by – David Frost, the broadcaster then suggested the name Nesuhi Ertegun. When Woosnam bumped into Ertegun at a party in Mexico City during the 1970 World Cup, he encountered a man who needed very little persuasion.

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Nesuhi and his younger brother Ahmet were the Turkish-born siblings behind Atlantic Records, the label that had given the world, among many others, Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin and Led Zeppelin.

By then part of the Warner Bros empire, they offered tremendous PR potential for the franchise. At the time, though, Woosnam and Toye were unconcerned about these investors’ status in the worlds of music and movies. “They could have been trash collection magnates for all we cared,” admits Toye. “We just needed their money as part of our Robin Hood business model – take from the rich and give to the poor, in this case the poor who had not yet come to want soccer in their diet.”

With backing in place for the New York franchise, Toye moved across from his role of developing the league to become the general manager of the newly christened Cosmos. Here he promptly embarked on what would become a four-year-long campaign to persuade Pele to sign for the club. When the great man finally acquiesced in 1975, the blossoming relationship between soccer and music was further cemented – the deal included the Brazilian being signed to Atlantic as a recording artist.

As general manager, Toye encountered differing levels of interest from each Ertegun brother. “Nesuhi certainly liked soccer very much. He was always at the game, always ready for a chat. Ahmet? I never saw him until things got really big.”

This distinction is confirmed by Dennis Tueart, the Manchester City and England winger signed by Cosmos in 1978 to replace the retiring Pele. “Nesuhi was the big football fan. He was very hands-on and was the one who came out to Manchester to do the deal. He used to travel the world looking out for music and for footballers.”

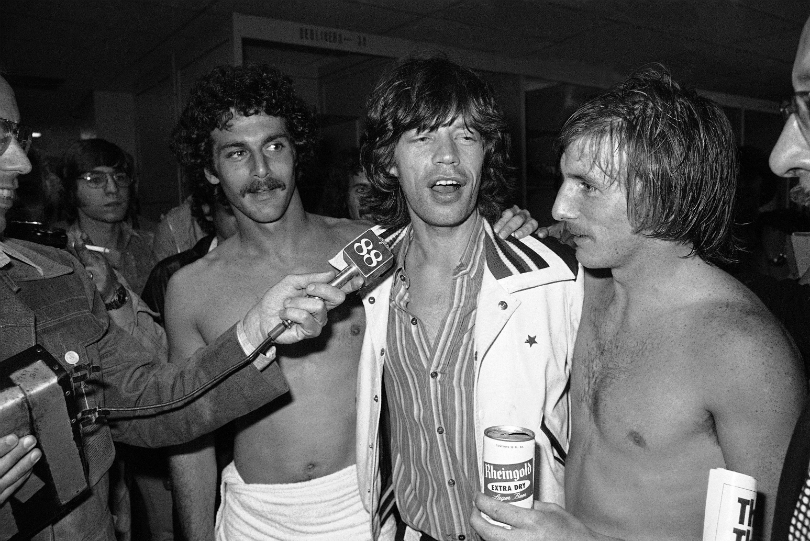

As Cosmos-mania rocketed, so too did high-profile patronage, with Mick Jagger and Robert Redford regulars in the dressing room at Giants Stadium. The club’s success also saw its owners become more involved in team affairs. Toye offers a colourful example of this. “Somebody from Warner told me that the brothers were very upset because we were a Turkish club without a Turkish player. So I gave way and signed the goalkeeper Erol Yasin. But he wasn’t the best, so he didn’t play.

This led to the very top brass of Warner, plus the Erteguns and me, going in limos to the helicopter terminal and flying over the river to the stadium in New Jersey so they could all argue with me and the coach Gordon Bradley that Yasin should be playing. This happened several times before we gave way.”

Tueart agrees that the owners could be demanding. “In my first season, we played against Minnesota in a play-off game and ended up losing 9-2. We had a meeting before the return game. [Warner Bros boss] Steve Ross came in and said he was disgusted with the performance against Minnesota.

He’d been in a conference on the West Coast discussing their latest project – the next Superman movie – but the 750 delegates only wanted to talk about the Cosmos losing 9-2. He said, ‘I felt embarrassed and I don’t like feeling embarrassed. We are the best. We pay top dollar. If you don’t want to join that philosophy, leave.’”

The owners’ increasing control ultimately did for Clive Toye, the man whose diplomacy and patience had, of course, secured them the ultimate prize of Pele. “Eventually my refusal to listen to anyone but myself resulted in me sending a memo saying, in effect: ‘Look, I’ve built this bloody thing up from scratch on your money but on my decisions and actions. We either continue to do so or else.’ They said ‘or else’ sounded better…”

When putting his time at Cosmos into perspective, Toye draws comparisons with recent events at Cardiff City involving owner interference. “I had at least three Vincent Tans,” he sighs, “with a couple more on the bench, someone’s son, another one’s future wife and an ex-American football coach all thrust upon the club. But after I left, it got worse. They ended up with two general managers – one at one end of the large club offices reporting to the Erteguns, and one at the other end reporting to the Warner mob.”

Los Angeles Aztecs: Elton John

"I saw [fellow Aztecs defender] Phil Beale the other day and asked if he could remember Elton coming to a game or being in the dressing room. He said: ‘No. Why? Was he part of the Aztecs?’”

More than 2,500 miles away on the West Coast, the owners of Los Angeles Aztecs were hoping – mainly through the recruitment of Elton John as celebrity investor and George Best as star player – to replicate the Cosmos’ success but on Californian soil.

Having joined the club in early 1976, John wasn’t a complete stranger to football Stateside. His cousin was Roy Dwight, the former Nottingham Forest winger who was part of a delegation that visited US in 1966 in the golden afterglow of England’s World Cup success. The party – also including Jimmy Greaves and commentator Kenneth Wolstenholme – had been charged with recruiting British teams to play in the US the following summer. The two-month-long tournament saw the likes of Wolverhampton Wanderers and Stoke City rebadged as the Los Angeles Wolves and the Cleveland Stokers.

Despite this familial connection, and despite those high-profile TV interviews directly beaming into American living rooms, Elton was actually rather hands-off when it came to the Aztecs’ affairs. Compared to the control exercised by Cosmos’ owners, when it came to the day-to-day management of the club Elton was both invisible and silent, a situation confirmed by Aztecs centre-back (and former QPR and Arsenal stalwart) Terry Mancini.

“My first club was Watford and I’d met Elton there on two or three occasions when he was just starting out. But I can’t remember seeing him at a game in LA. He was huge by then so I guess he never had the time. I saw [fellow Aztecs defender] Phil Beale the other day and asked if he could remember Elton coming to a game or being in the dressing room. He said: ‘No. Why? Was he part of the Aztecs?’”

As he’d recently ascended to the chairman’s office at Watford – and with a punishing tour schedule to uphold – the Aztecs slipped lower on Elton’s list of priorities. Not that, argues the club’s then-twenty-something coach Terry Fisher, it was ever intended that the star was going to be heavily involved in team affairs in the manner that the Ertegun brothers were out east.

“Elton had a 25 per cent interest in the club only for the rights to use his name as an owner,” Fisher reveals. “He had no involvement in the day-to-day running of the club, nor any of the player signings. Over the two seasons he was involved, he probably went to three or four games.

“The hope was that Elton would play concerts after matches to raise money. His agent stopped him, so we never actualised the potential Elton could have brought in terms of money. He was just an owner.” Despite George Best’s crowd-pleasing trickery, the Aztecs could not mirror that Cosmos glamour, even with many Hollywood A-listers living on their doorstep. “There were stars who came into the dressing room,” recalls Mancini, “but I wasn’t a star-gazer and concentrated on the football.”

Fisher is certainly keen to caution against anyone comparing the two clubs. “The Cosmos had tons of big corporate money and we were a small, patched-together ownership of doctors and lawyers. Yes, we were in LA and they were in New York, but that’s where it ended.”

Philadelphia Fury: Frank Barsalona (music agent), Rick Wakeman, Paul Simon, Peter Frampton

"I was living in Switzerland and would fly from there to New York because there wasn’t a direct flight between Geneva and Philadelphia. Then I’d get in a car and arrive in Philadelphia late, check into a hotel, go to the game and then fly to wherever the next gig was."

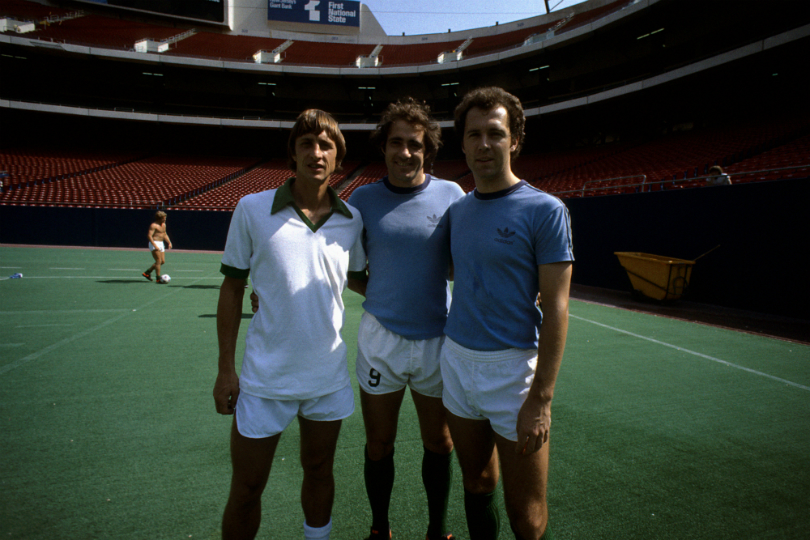

Back on the East Coast, during the winter of 1977, another patched-together ownership was being assembled, one that enjoyed even deeper connections with the music industry than either Cosmos or Aztecs. When the league made available a franchise in Philadelphia, Nesuhi Ertegun suggested to music agent Frank Barsalona that he should take it on.

As the owner of the Premier Talent Agency, Barsalona mapped out the touring itineraries of the biggest rock bands of the day, among them Led Zeppelin and The Who. A canny but honest operator, he was quick to see how music and soccer overlapped.

“The demographics are the same,” he told Sports Illustrated. “Entertainment for the 14-35 age group.” However, unlike his contemporaries in Los Angeles, he didn’t want the two inextricably intertwined. “We’re not going to put on rock extravaganzas at half-time or anything. This is a business. Lipton owns the New England franchise and they’re not going to give away tea bags up there.”

Another British act on Premier’s roster were Yes, the prog-rockers who, like compatriots Led Zep, were also signed to Atlantic. Nesuhi Ertegun recommended to Barsalona that his first port of call when scouting for investors should be the band’s football-obsessed keyboard player, one Rick Wakeman.

It was a good shout. Wakeman signed up immediately and was soon joined by several other music industry figures, a rag-tag amalgam of performers (Paul Simon, Peter Frampton), record label supremos (including Chrysalis Records co-founder Chris Wright who would later take over QPR) and various managers, including the Rolling Stones’ tour boss Peter Rudge.

Mick Jagger, that stalwart of the Cosmos dressing room, came close to putting some cash into Fury himself, but apparently demurred when an advisor judged it to be an investment he might never see again.

Wakeman had no such qualms and was already tuned in to what was happening in the NASL. Yes manager Brian Lane had his office downstairs from that of a man called Ken Adams, a figure Wakeman describes as “the first football agent. He was looking after players who were coming into their twilight years, those who – if they were lucky – got a testimonial before being put out to grass.

Some really good players ended up driving cabs or owning pubs, so Ken started up this agency taking these players over to America. And it was wonderful for us. In the downstairs hall, myself, Jon Anderson from Yes and a couple of our road crew had five-a-side games with Rodney Marsh, Stan Bowles, George Best, Bobby Moore… We lined up and picked sides like in the school playground!”

Having speedily signed up to the Fury’s cause, Wakeman and Lane were commissioned by Frank Barsalona “to go get us a team”. The offer was irresistible. “You’re 27 years old and someone has given you an open cheque book to go and buy a team. It was fantasy football. We had a hand of cards to offer, too. We were offering players three or four times what they were earning in England, plus a house, a car and all the other bits and pieces.”

Two particularly combative midfielders were at the top of Wakeman’s shopping list. “I’d always dreamed of Alan Ball and Johnny Giles playing together – similar build, both little terriers, both 100 per cent guys in every respect. Then we needed a goalscorer. I knew Peter Osgood as he was on Ken Adams’ books and was ready to go to America.

Both Ball and Osgood were playing for Southampton and that’s where I first met Lawrie McMenemy. Lawrie, being an ex-sergeant major, didn’t know what the hell to make of me. I had hair going down my back and was wearing weird T-shirts and green PVC trousers. Then I told Lawrie what I was going to be paying these guys. ‘Well, they’d be stupid not to go, wouldn’t they?’”

Fury’s opening match of their debut season hinted at the culture clash between the English game and its North American incarnation. “It was against Washington Diplomats, Jimmy Hill’s side.

Unfortunately, the night before, the mayor of Philadelphia had thrown a party for the players which had finished very, very late. It was a quiet dressing room the next day. I remember Alan Ball, who hadn’t gone to the party, reading the riot act to them. ‘This is a wonderful chance for everybody. This is not party time.’ But Jimmy told me the mayor of Washington had done the same thing for his players. Theirs was a very quiet dressing room too.

It was a 0-0 draw – at least until that ridiculous shootout they used to do.”

Even if Wakeman didn’t necessarily agree with all of the innovations that the NASL honchos had applied to his beloved sport, he did applaud several aspects of the American version that he felt could improve the English game, such as increased sponsorship and modern stadiums.

Suitably enamoured, he made it his duty to watch his team as often as the life of a rock star would allow. “We were on the road the whole time, but I got to as many games as I could. I was living in Switzerland and would fly from there to New York because there wasn’t a direct flight between Geneva and Philadelphia. Then I’d get in a car and arrive in Philadelphia late, check into a hotel, go to the game and then fly to wherever the next gig was. It was nuts.”

Despite this cross-continental fanaticism, Fury were far from a success. The team finished bottom of their division in their opening season, although – thanks to the often unfathomable NASL rules – still found themselves in the end-of-season play-offs.

The club’s gates were a pale shadow of those of their Cosmos cousins up the coast. The average attendance for home matches in 1978 was just a shade over 8,000; that same season, Giants Stadium welcomed an average of almost 48,000 punters per game. Peter Osgood was a particular disappointment for Fury, managing just a single goal in 22 appearances. For the second year of the Philadelphian NASL adventure, he was replaced by another flamboyant – but more prolific – striker, Frank Worthington.

While Worthington’s goals helped to improve fortunes during that 1979 season (Fury reached the semi-finals of the American Conference), it’s fair to say that the club wasn’t being run along the strict, unbending lines that had secured great success for Cosmos. Certainly some of those Fury investors seemed content to remain silent partners. “I personally never saw Paul Simon at a game,” admits Wakeman, “nor some of the other owners. And I don’t think we ever had a single board meeting.”

With those disappointing attendances further diminishing, the whole venture became unsustainable and Philadelphia Fury were wound up in 1980, the franchise moving to Montreal. Mick Jagger’s advisor might have been proved correct, but Wakeman regrets nothing. “It did cost me a lot of money,” he concedes, “but I don’t regret one penny of it. I had the most wonderful time and made the most wonderful friends.”

In New York, Clive Toye – the man who, with Phil Woosnam, had nursed the league through its difficult infancy – was alarmed at the way clubs were being run. “I recall sitting next to [Dallas Tornado owner] Lamar Hunt at a league meeting with these newcomers in attendance, so many with gold rings and necklaces and open shirts. Lamar said to me, ‘It looks like a different league’.”

The success of the NASL – at least during Cosmos’ two glamour-heavy, championship-winning seasons in ’77 and ’78 – ultimately kicked the blocks out from underneath it. The rich and famous were attracted to this fashionable plaything, with scant concern for the sport’s grassroots or longevity. Without firm foundations for the future, and devoid of significant television income and exposure, the league spluttered on until its final collapse in 1984.

Clive Toye concludes: “We should have reduced to 12 clubs – 12 clubs with success at hand and the long term in mind. Instead we expanded to 24 and a host of new faces, new clowns and a couple of new crooks arrived.” His musical analogy makes a fitting epitaph. “The music in the Erteguns’ ears certainly helped to compose the final dirge.”

This feature originally appeared in the January 2014 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe!