Where there’s smoke, there’s fire: Independiente vs Racing Club, Argentina's 'real derby for real fans'

Boca-River isn't the only derby in Buenos Aires. For the August 2008 FourFourTwo magazine, Daniel Neilson assessed the turbulent, hyperlocal and often violent history of the Avellaneda derby...

Six battered buses speed through the streets of downtown Buenos Aires. Ahead of them, police bikes clear traffic and cut red lights. Trailing behind are four police cars and two vans full of riot troops. Inside the buses are the hardcore fans of Independiente, en route to the most important game of their season: the derby against hated rivals Racing Club.

Legs, arms, heads and flags protrude from the windows and doors. Drums resonate from within and chants drift across the wide avenues of the Argentinian capital. FourFourTwo is in the third bus, squeezed between two bass drums, several sacks of ticker tape and 60 very drunk and stoned fans all spitting out debasing songs about their enemy:

An old man being hiked up into an ambulance tears off his oxygen mask and hollers “Dale Rojo” (Come on Reds) before collapsing back on the stretcher

"Independiente is an addiction

And I’m with the craziest barra of the lot

I follow the reds wherever they go

Boca are going to run

And Racing fans? We're going to kill ‘em."

As the sirens and chants announce the arrival of the barra brava (hooligan group), other Independiente fans walking the streets stop and cheer them along; an old man being hiked up into an ambulance tears off his oxygen mask and hollers “Dale Rojo” ('Come on Reds') before collapsing back on the stretcher.

Not lost on the barra, the buses slow down and the mob cheer for the old guy. The next minute, a different atmosphere: a group of Racing fans throw bottles, smashing a couple of bus windows.

The police are twitchy, and understandably so: meetings between these two teams have rarely passed off without violence. Sometimes scuffles, occasionally death. It is the one game on the calendar that almost everyone in the city advises against going to. And for security reasons, home team Independiente will host Racing at the neutral Velez Sarsfield stadium on the other side of Buenos Aires.

Derby capital

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Argentinian football is dominated by derbies, or clasicos. Of the 20 teams in the Argentinian Primera Division, 12 are based in Buenos Aires, with a further five less than a two-hour drive away. The capital, a city of 14 million people, is both the centre of life in Argentina and its footballing heart. Local clasicos are numerous.

The nearby city of Rosario is home to Newell’s Old Boys and Rosario Central, a fierce provincial derby, while even closer to Buenos Aires, a similar animosity exists between Juan Sebastian Veron’s Estudiantes and Gimnasia in the city of La Plata.

Within BA itself, however, three derbies dominate the calendar. San Lorenzo versus Huracan is an important clásico, although the latter have yo-yoed between the first and second tiers in the past decade, causing the match to lose its bite. And even football-phobes are aware of Boca Juniors-River Plate.

Recent superclasicos have been stale, though, partly because of the severely limited allocation of away tickets, but mainly because of the violent internal feud between rival factions of River’s barra, which has led other fans to stay away. Supporters now do little more than blow up a few balloons; a far cry from the spectacular displays that once defined the superclasico.

The Argentine Dundee

Boca and River may divide the whole country, but Independiente vs Racing – third and fourth in terms of fanbase – is the tastiest derby in Buenos Aires.

Boca vs River might be the most watched clasico, but Racing vs Independiente is much more passionate. You have to be a real fan to follow these teams

A few days before the game, FourFourTwo travels to the industrial port neighbourhood of Avellaneda, home to both teams, just across the southern border of the city, to watch Racing train.

By the pitch, a handful of diehard fans are watching the final preparations for the derby. Ricardo, an unshaven middle-aged man with a missing tooth, explains the importance of the derby: “Boca vs River might be the most watched clasico, but Racing vs Independiente is much more passionate. You have to be a real fan to follow these teams. And when they play. Wow. What an atmosphere.”

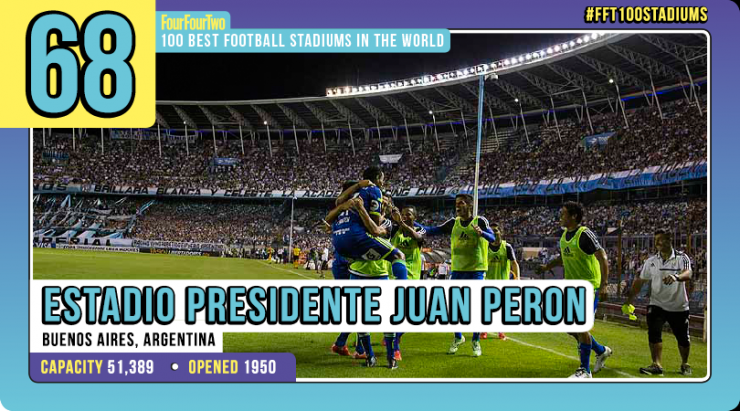

From the platform of the train station, high above the city, the source of this intense rivalry is obvious. Below us is a building site where Independiente’s stadium is being rebuilt. A mere 200 metres beyond that is the 1950s Cilindro of Racing. Think Anfield and Goodison across Stanley Park, but much, much closer. Only Dundee and Dundee United can match them for proximity.

It is a local derby in the truest sense. In Avellaneda, Independiente and Racing graffiti compete on the walls. There are two types of bars: Racing bars and Independiente bars. Two types of restaurants: Racing restaurants and Independiente restaurants. And two types of people: Racing fans and Independiente fans.

Racing’s Juan Domingo Peron Stadium overshadows the ramshackle buildings of the area. Built in 1950 with government money, the stadium is presently home both to Racing, and, annoyingly for them, the temporarily homeless Independiente.

Turbulent times

Independiente fans and Racing fans live side by side around here. That used to be OK, but what used to be a fiesta has become a battle

In his salon under the haunches of the stadium, barber and Racing fan Daniel Bazan explains the importance of the derby. “It is the most important day in this neighbourhood and something everyone lives for in the weeks before the game. Independiente fans and Racing fans live side by side around here. That used to be OK, but what used to be a fiesta has become a battle. Now people get injured, killed... It’s such a shame.”

Jorge ‘Titi’ Jaula, getting his short back and sides, sold tickets to Racing games for 53 years before retiring last week. “You used to take the whole family,” he agrees. “Now if your son goes to the game, you don’t know whether he’ll come home. They just can’t control the violence. No one’s taking responsibility. The clasico shouldn’t be like this, it should be a celebration.”

Trouble at the Clasico de Avellaneda began to emerge in the 1980s with organised firm meetings at predetermined places, usually well away from the stadiums. In 1997, the first hooligan-related murder took place, when a member of ‘the Racing Stones’ barra was allegedly killed by an Independiente barra. Then, on derby day in 2000, 100 fans were injured in a huge street fight. In September 2001, 17 people were stabbed in one brawl.

Incidents increased over the years, culminating in one horrific fight on February 2002. Independiente were playing Racing in the Peron Stadium. All morning there had been scraps, but worse was to come.

A tradition among the Racing barra was to have a barbecue in the club’s ground before the game. Such is the proximity of the rival clubhouses that Independiente’s barra could literally throw stones at Racing’s clubhouse. The first bombardment injured a Racing member.

An angry mob then stormed towards Independiente’s stadium. The Barra de Rojo were waiting for them, waving guns. In front of hundreds of fans buying tickets there was a gunfight. By the end of the evening there were 25 people in the nearest hospital and 22-year-old Independiente fan, Gustavo Rivera, was dead. It was the worst football-related violence in Argentina for almost a decade, and since.

NEXT: Argentina's football debt to England

The crazy Ingleses

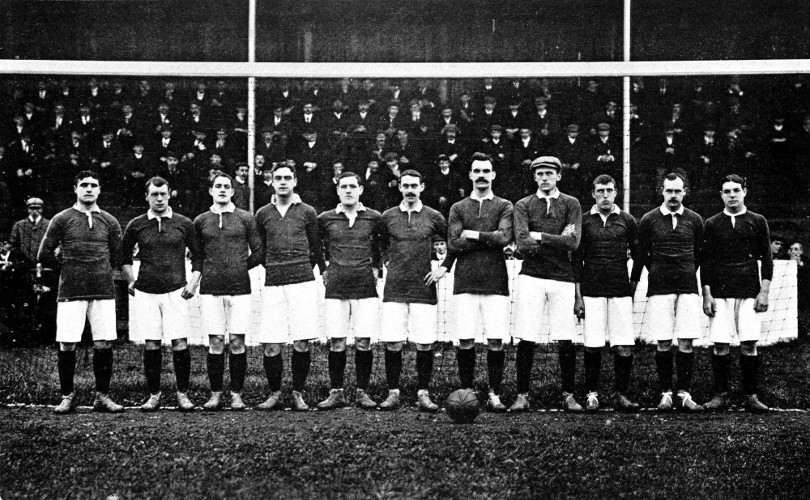

Football first rolled down the Argentinian gangplank with the arrival of British railway engineers, and the first recorded game in Buenos Aires took place on May 9, 1867, organised by English brothers Thomas and James Hogg.

Fascinated by the game these Ingleses locos (‘crazy Englishmen’) were playing, Argentinian workers, often from Italian backgrounds, soon adopted it and formed their own clubs. At the beginning of the 19th Century more than 300 clubs were set up, many with English names that still exist today: Boca Juniors, River Plate, Newell’s Old Boys and Arsenal.

Barred by their English bosses, disgruntled employees secretly decided to start an ‘independent’ team, and Independiente was born

Club Atletico Independiente was officially formed on January 1, 1905 by Argentinian employees of a shop called To The City of London. The business, owned by Englishmen, formed a football team called Maipu Football Club, although local workers were barred from joining. In a bar downtown, disgruntled employees secretly decided to start a team ‘independent’ of Maipu, and Independiente was born.

To officially create a football club, they required a leather ball and a uniform. The ball they had, but they couldn’t afford a kit, so they utilised that of the recently defunct St Andrews FC (the blue and white colours with the St Andrews cross is still used as Independiente’s away kit).

It wasn’t until 1910 that they changed their kit colour, allegedly after their president went to see Nottingham Forest play on their Argentinian tour in 1905. So impressed was he with Forest’s style of play, he decreed Independiente should now play in red. It soon earned them the nickname ‘the Red Devils’.

Racing were formed in 1901, when a group of college students founded Football Club Barracas al Sud. The club was renamed Racing Club in 1903 after one of the associates saw the name of Racing Club de Paris in a French newspaper. Their blue and white kit was a nod to the Argentinian flag.

The two teams would have to wait a few years to meet, but as soon as Independiente settled in the stadium two blocks away, the rivalry was cemented. On September 6, 1907 the first recorded match took place, Independiente winning 3-2.

Racing dominated the amateur era of Argentinian football. Their triumph in 1913 was the first time a team had won a title without any British players

It was Racing, however, who dominated the amateur era of Argentinian football, winning the league every year between 1913 and 1918. Their triumph in 1913 was also the first time a team had won a title without any British players.

Kicking off

On December 12, 1915 was when the real animosity began. A controversial decision by the Argentinian Football Association (AFA), for reasons unrecorded, overturned a 2-1 win by Independiente, awarding Racing the victory and consequently the championship.

It was during this time that a newspaper report nicknamed Racing La Academia, the Academy, thanks to the high-quality players it was producing. It still does: recent alumni include Sergio ‘brother of Javier’ Zanetti, Diego Simeone and ex-Argentina coach Alfio Basile.

A strike by players over pay ushered in professionalism in Argentinian football from 1931. On the last weekend of the first tournament, Independiente played Racing in a game already dubbed El Clasico de Avellaneda. Racing won 7-4.

It was Independiente, however, who enjoyed the most success during the 1930s. It was an era characterised by goals, lots of them. In 1938 they scored 115 goals in 32 matches and in 1939, 103 goals in 34, many via the foot of Paraguayan Arsenio Erico, whose 293 goals remains an Argentinian record.

In 1964, they became the first Argentinian team to win the continent-wide Copa Libertadores, beating Pele’s Santos twice en route. It is by far the most important title for a Latin American team and one by which the success of every Argentinian team is judged. In 1965, they won it again.

It was also during this period that barra brava groups began to form, vowing to ‘follow the team, wherever they go, to support them and to repel the aggression of opposing fans’. Nicknames of the early leaders, among them Banana and Pistola, have passed into fan folklore.

The 1970s were known as the ‘Golden Age’ for Independiente, cementing their reputation as the Rey de Copas, ‘King of Cups’. They became the only team to win the Copa Libertadores four times in a row, from 1972 to 1975, and also won the Copa Intercontinental (1973) and Copa Interamericana (1973-75). The team’s star, Ricardo Bochini, who played from 1972 to 1991, is not only adored by Independiente players, but is also Diego Maradona’s idol.

By the 1990s, however, the Red Devils were losing their fire. Despite a couple of title wins, the last in 2002, Independiente have struggled domestically. To make matters worse, Boca Juniors recently overtook their record of international cups. By February 2006 they were $26 million in debt and placed in receivership.

In 1983, a last-day victory at already-relegated Racing would give Independiente the title. They won 2-1 and embarked on a slow celebration lap in front of Racing’s home crowd. It still rankles today

Racing’s history is less illustrious. Their only Copa Libertadores success came in 1967, when they also beat Celtic to win the Intercontinental Cup. They were relegated in 1983 after a controversial decision by the AFA, who had instigated a complicated average points structure for promotion and relegation.

The club had already been condemned to the ‘B’ when they played Independiente on the last game of the season, but they were desperate to win: defeat would hand their bitter rivals the title. Independiente won 2-1 and embarked on a slow celebration lap in front of Racing’s home crowd. It still rankles today.

Tensions building

Going into this week’s game with only three matches of the season remaining, Racing find themselves in a very similar position. If they lose the clasico they will certainly have to play the promocion, a play-off to determine who will be relegated. Racing fans are not happy.

In between screaming at new manager Juan Manuel ‘we’re not going to be relegated’ Llop to turn up the tempo and stop smiling so much, toothless fan Ricardo explains the discontent with the current administration.

In 1999, Racing filed for bankruptcy and, for a few weeks, no longer existed. Thousands of fans protested in front of the congress building asking for help. It came in the form of Blanquiceleste, a private company who bought the team’s rights until 2011.

Racing now are the only top-flight team owned by a company rather than being a cooperative. “We though it was good for the team,” moans Ricardo. “But they change the manager all the time. No one has enough time to make a difference. Racing fans are suffering.”

Another fan, Oscar, is equally indignant. “Most fans want Blanquiceleste to go. They’re putting all the money in their pocket and nothing into the team.”

This fury was taken to the streets two weeks ago, when hundreds of Racing fans protested outside the AFA headquarters, calling for Blanquiceleste’s dismissal and elections to find a new administration.

NEXT: Match day

It’s early winter in Argentina and on a cold evening before the game, FourFourTwo returns to Avellaneda to meet an Independiente fan known as El Abogado del Diablo, ‘The Lawyer of the Devil’, or Tony to his friends, a member of Grupo Diabolico.

Under the strip light of a pizzeria, the group meet every week, though Tony is quick to point out that they’re one of many non-violent organisations who, along with Infierno Murguero, a traditional Argentinian carnival troupe, provide the drums for the terrace chants. He explains how the bombos (drums) are the heartbeat of an Argentinian crowd and that they are “at the service of the fans”.

To the match

As the convoy of buses approach the neutral Velez Sársfield stadium, riot police march out, creating a corridor from the door of the bus directly into the stadium. We have tickets but they don’t need to be shown. Those in charge of the barra drag people out of the bus as quickly as possible. Slow movers are given a clip round the ear.

A water cannon tank moves into place, just in case. Thousands of fans, waiting to get through the police frisks, spot the barra and begin to sing. Song sheets with especially composed lyrics are handed out to everyone: 'Blanquiceleste don’t bullshit / you are owned by a company / you’re going to be relegated.'

Once ushered inside the stadium, the final preparations are put into place. Flags are tied up, including a couple stolen from Racing. The Grupo Diabolico, with Tony at the helm, bang away. Red flags are handed out to the 10,000 fans squeezed in to the standing terrace at the north end of the stadium. At the other end, a smaller crowd of blue and white defiantly chant heartily, despite Racing’s perilous position.

Surges in the crowd flatten dozens of people. Police start pulling out bodies; several are carried away. The crowd continue singing

When Independiente emerge onto the pitch, ticker tape turns the air white momentarily, before smoke bombs paint it red. Surges in the crowd flatten dozens of people. Police start pulling out bodies; several are carried away. The crowd continue singing. The noise is thunderous.

As the Racing team appear, ticker fills the other end of the stadium, and the barra time their entrance with the team and fill the gap in the middle with blue and white flags.

Independiente fans are in buoyant mood – and they have every right to be. They are coming off a winning streak, in fifth position in the league and have the likes of national team player Daniel Gaston Montenegro and Napoli-bound top scorer German Denis among their starting 11. Racing, on the other hand, are in last place and have only won twice all season.

From the outset it’s a messy affair. Neither team can afford to lose and the players seem worryingly aware. There are almost no shots from either side in first half. There’s plenty of endeavour but little flair.

By the second half, the wrath of Independiente’s supporters has turned from Racing’s fans to their own players. At the other end of the stadium, Racing hit the crossbar and their fans begin to believe. The noise from 3,500 blue-and-whites drowns out the 26,500 reds.

At the final whistle Racing are celebrating, despite the stalemate, but it hasn’t lifted Racing out of the relegation zone. With two games to go until the end of the season the same rules that saw them relegated in 1983 – based on a three-year points average – may have the same effect, or it may actually save them.

After today’s draw, their average points mean they will have to compete in a two leg play-off to beat relegation, a win would have meant safety. Independiente fans taunt Racing with signs that reads ‘Volves? 1983-2008’ ("Returning?")

We played badly, but we are in love with the institution, not the players; they come and go. Being a fan is a symbol of identity, but it is also something transcendent

After the game a diehard Racing fan called Claudio Borghi speaks to the assembled press… as recently-appointed coach of Independiente. “I’m leaving sad. Speaking as a coach, not a fan, I hoped Independiente would win, we needed three points. And it’s always good to win a clasico.”

As they wait to leave the stadium, Independiente fans are in glum mood. Some are already complaining about Borghi being a Racing fan. “Maybe he just didn’t want us to beat them,” says one.

Most of the ire, though, is reserved for the players. “They are just lazy, they don’t care about El Rojo and they don’t understand how important the clasico is for us,” another moans.

Tony is more philosophical: “We played badly, but remember we are in love with the institution not the players; they come and go. For me being an Independiente fan is a symbol of identity. But it is also something transcendent.”

For Racing, however, the present situation is much more tangible. The thought of relegation is unbearable for fans. But there is a glimmer of hope: On June 3 a federal judge suspends Racing’s owners, Blanquiceleste, for not paying wages.

It marks the death of a hated regime. But for Racing? The future is uncertain, but the terraces will remain full. It may mean no more clasico fiestas for a while, but the humiliation will never be forgotten.

This article first appeared in the August 2008 edition of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe!