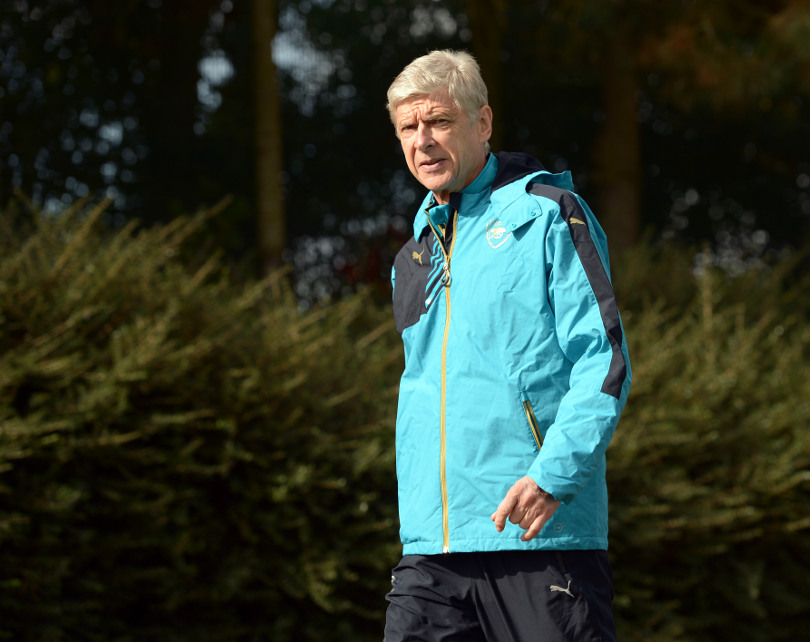

Why Arsene Wenger is standing at his most defining crossroads yet with Arsenal

The Frenchman's football blueprint could still be vindicated this season, but his north London rivals are worryingly instilling it more successfully, argues Alex Hess...

While the truckloads of contempt dispatched his way after Sunday’s Old Trafford surrender might suggest otherwise, a glance at the table offers a reminder that this could yet be a quite magnificent season for Arsene Wenger. Even more than that: it could be his ultimate vindication.

As Wenger has often reminded us, it’s not a coincidence that Arsenal's barren years have coincided quite precisely with the arrival in English football of oil-rich billionaires willing to bankroll success at any cost. And throughout this era Wenger has stuck firmly to his guns, preaching prudence over turbulence and admirably refusing to be peer-pressured into big spending for its own sake.

Success bought is quite different from success earned, and Wenger would tell you that anything won with a sugar daddy comes with a bitter aftertaste

Stick to your guns

It'd be Wenger's great exoneration if this season was to conclude with his fastidiously run club striding into the power vacuum created by the tail-spinning magnates of Man City and Chelsea

To Wenger – and to plenty of others – this is not just an economic argument but a moral one. Success bought is quite different from success earned, and he would tell you that anything won with a sugar daddy comes with a bitter aftertaste.

Wenger may not have seen much silverware during the years since Roman Abramovich’s arrival in 2003, but he could always invite his critics to take a glance at the wider world for proof that sustainable economics is a practice founded on real-life ethics rather than the sort of pantomime stinginess invoked by the “SPEND SPEND SPEND” brigade.

The argument holds weight, too. Part of the reason Wenger's habitual clambering for the moral high ground has irked so many people (Jose Mourinho, perhaps not coincidentally, chief among them) is because they suspect he has a point. Against this backdrop, then, it would be Wenger's great exoneration if this season was to conclude with his fastidiously run club striding into the power vacuum created by the tail-spinning magnates of Manchester City and Chelsea.

An emphatic triumph for stability and restraint over cash-fuelled short-termism, a sporting victory that doubles up as a moral one too. And, six points off top with 33 to play for, it could well happen. Crisis – what crisis?

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Much to lose

The crisis emerges when you consider the likely alternative: that Arsenal are pipped to the title not by a financial juggernaut, but by Leicester or Tottenham

Except the crisis – or at least the promise of one – is very real. It emerges when you consider the likely alternative: that Arsenal fail once again to step up when it counts and are pipped to the title not by a financial juggernaut, but by Leicester or Tottenham

That would be Leicester, whose squad was thrown together for a fraction of the cost of Wenger's. Or Spurs: not just Arsenal’s local rivals but the only top-flight club to make a profit on transfer business over the past five years.

With the middle ground between vindication and humiliation almost non-existent, Wenger desperately needs his big players to deliver. In one sense, his two concessions to mega-money spending, Mesut Ozil and Alexis Sanchez, have already proven worthwhile as the club’s outstanding players this season and last.

And yet with the finish line in sight, both are in danger of abjectly inverting the 'great player' proviso of producing the biggest performances on the biggest occasions. With each game a potential season-definer, both are struggling for form, neither able to inject their team with a semblance of backbone as an insipid defeat unfolded at Old Trafford.

In contrast, Leicester's talismanic attackers are showing little sign of slowing. Jamie Vardy and Riyad Mahrez both led the charge valiantly in their side's kitchen-sink effort against Norwich, and were unlucky not to do the same against West Brom on Tuesday night. Behind them, N’Golo Kante continues to dominate, his display at the Emirates a fortnight ago one of the standout individual showings of recent years. The three cost a tenth the price of Sanchez and Ozil.

Mediocrity doesn't win

Though each would undoubtedly make a charming son-in-law, none have made the step from decent to decisive

Another Wenger trope, that his project is to foster a team of youngsters who will grow together, is also wearing thin. If the mass poachings of Cesc Fabregas, Samir Nasri and Robin van Persie weren't enough to expose this fallacy, the middling advances of the ones who hung around should.

Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain, Aaron Ramsey and Theo Walcott are closing in on a quarter-century's service between them, the latter two approaching what should be their peak years. Though each would undoubtedly make a charming son-in-law, none have made the step from decent to decisive, their penchant for selfies expertly capturing the lack of the nastiness that so often drives sport’s truest winners.

Jack Wilshere may yet come good but, with nine Premier League starts over the past two seasons, the spirit being rekindled is less Paul Gascoigne and more Kieron Dyer.

If Arsenal’s kids are either too nice or too fragile, Spurs' youngsters are both aggressive and durable, Mauricio Pochettino’s squad reaping the benefits of the sort of scrupulous training and dietary regimes that once had Wenger cast as a revolutionary.

Harry Kane and Eric Dier have combined youthful exuberance with an injury-averse robustness to become among the league’s best in their positions. Dele Alli’s season has been a one-man masterclass in how to match impudence with end product: if they want their England places back, Wilshere & Co. should be taking notes.

Holes at the back

Arsenal has, for the best part of a decade now, become a club renowned for calamitous defending

Once the club of Tony Adams and Martin Keown, and despite Steve Bould’s training-ground presence, Arsenal has, for the best part of a decade now, become a club renowned for calamitous defending.

And even when they aren’t actually making mistakes, Wenger’s centre-backs have called to mind the “broken windows theory” of urban crime management: that the appearance of dereliction is enough to invite further crime.

Meanwhile, White Hart Lane has become home to the league’s best defensive pairing, Jan Vertonghen and Toby Alderweireld offering a fine balance of modern-day dexterity and old-school grit, and Kevin Wimmer sound back-up. In short, Pochettino has taken Wenger’s blueprint and added the vital ingredient: steel.

With the pressure on, Sunday’s trip to Manchester saw Arsenal pitifully pass up the chance to take vital points from a major ground, a big-stage bottle job if there ever was one. In the weeks prior, Leicester and Spurs had gone to the same town – to face title-challenging City rather than a depleted United – and produced the two performances of the season. Right now, the contrast is stark.

Bad losers

Wouldn’t a truly bitter loser instill in his players a far greater fear of failure

Wenger admitted on Sunday that he is a "bitter loser" – but perhaps the problem is that he's not bitter enough. Think back to the night in 2001 when Bobby Robson, shocked by Arsenal’s antics in the wake of defeat, remarked that Wenger and his players "needed to learn how to lose".

He was right, but Arsenal’s bad losers went on to win the Double that season. Fifteen years on, this seems a very different squad and a very different Wenger.

Wouldn’t a truly bitter loser instill in his players a far greater fear of failure (the sort exhibited by Spurs each week)? And show a greater intolerance of mediocrity within his own ranks (the sort that saw Pochettino instigate his mass clear-out)?

Michael Cox: Arsenal lack midfielder with guile

Six memorable Emmanuel Eboue moments

Should Arsenal fail to win the league – and barring a Manchester City revival – Wenger's problem will no longer be that the playing field has been tilted in favour of the wealthy few. Nor will it be that his methods are fundamentally flawed.

It will be that there are others doing his way, better. Which moves the case for his defence away from the economic and the moral, and back to the purely practical – and renders it not much case at all.

If this all seems like accentuating the negative, then a glance at the table assures that the league title is comfortably within Arsenal’s reach. This season could be Wenger’s ultimate success.

The problem is, it could just as easily be his ultimate failure.