Why Brendan and Jose's latest face-off could be their most fascinating tactical battle yet

Thore Haugstad weighs up the intriguing prospect of Rodgers' daring 3-4-3 against his old colleague's 4-2-3-1 ahead of their League Cup clash...

Brendan Rodgers has been a tactical improviser over the last 18 months, devising a series of new systems to counteract key absences and maximise the talents of whoever is available. The latest invention off the conveyor belt is a flamboyant 3-4-3 formation and, if it's true that there can be no genius without a touch of madness, this particular scheme seems to have a bit of both.

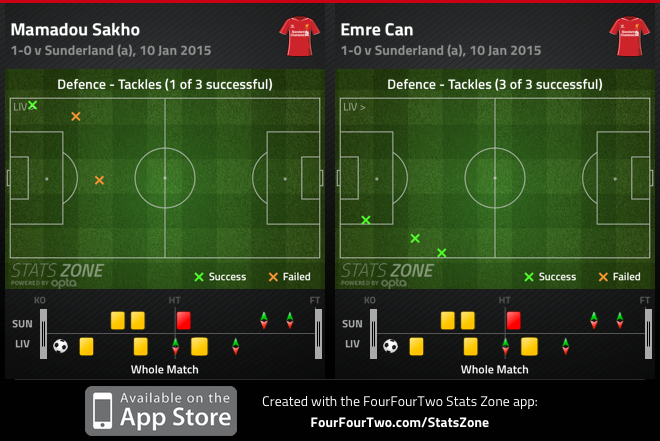

The strategy has served Rodgers well. Liverpool have won four of their last five league matches despite the devastating loss of Daniel Sturridge to perpetual muscle injuries. Underpinned by a backline usually consisting of Mamadou Sakho, Martin Skrtel and Emre Can – a trio some might find susceptible – the Reds have kept clean sheets in three straight away league matches, an improbable run started after the 3-0 defeat at Old Trafford on December 14.

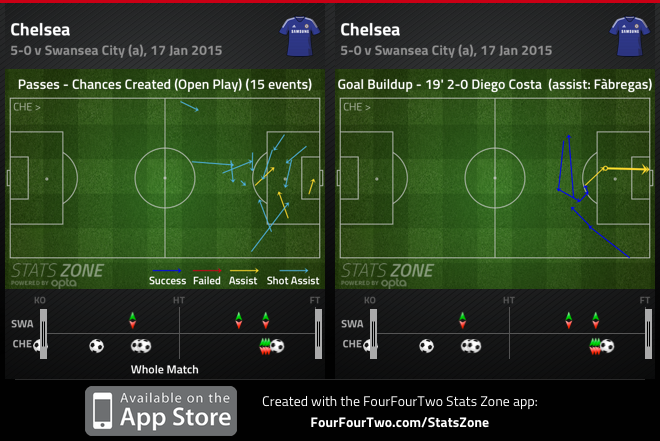

However, the recent away day bouts with Burnley, Sunderland and Aston Villa shrink in comparison with the challenge of tonight’s encounter; the opener in a two-legged semi-final in the League Cup, in which Liverpool host a Chelsea side confident after Saturday’s 5-0 win at Swansea. If Rodgers retains the 3-4-3, as seems likely, his system will create a handful of numerical disparities against Jose Mourinho’s 4-2-3-1.

That hands us an intriguing match-up and, while parts of the regular personnel might be rotated for the evening, the functions of the two systems should not. Drawing up their tactical blueprints, both managers will have a list of advantages and drawbacks to consider.

The men in the middle

For Rodgers, the installation of the 3-4-3 has recovered elements of the high-tempo style that disappeared with the loss of Sturridge and the exit of Luis Suarez. Liverpool are notably expansive in possession.

The wing-backs hug the touchline in advanced positions; the two central midfielders hold; the two attacking midfielders behind the lone striker alternate between staying between the lines, drifting wide and running in behind the defence. Their central positioning enables Liverpool to play the ball directly to the front trio, who can then combine to cut through the heart of the defence.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

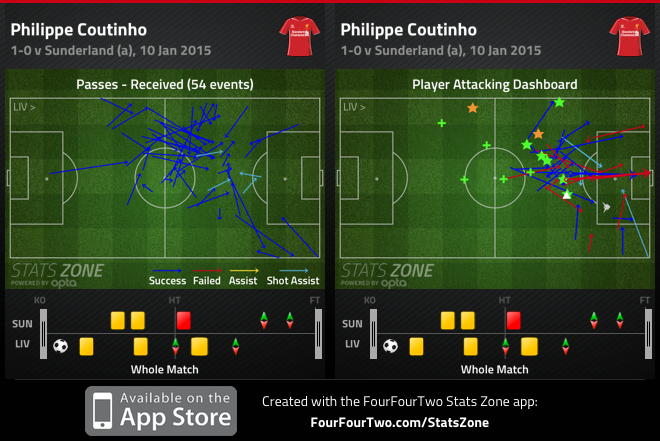

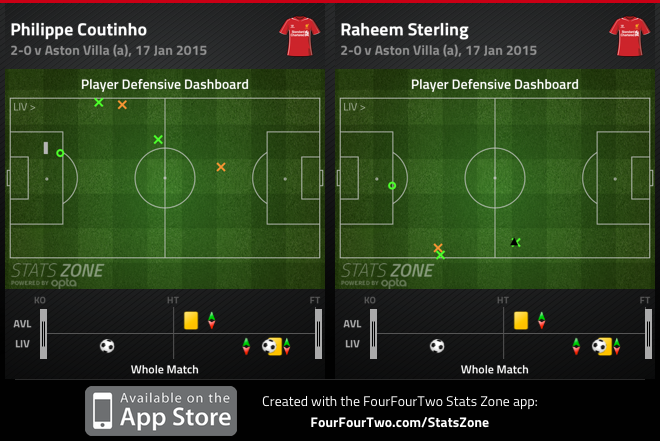

The two attacking midfielders might well be Mourinho’s main concern. With the wing-backs stretching play, the playmakers – usually Philippe Coutinho (left) and Adam Lallana (right) – can, together with the two holders, achieve a four-versus-three situation in the centre. They will also lurk behind Chelsea’s double pivot, particularly in the pockets of space near the wing-backs. Coutinho is lethal here, cutting inside to dribble and slip through incisive passes for reverse runs.

It suits Chelsea less. One of the few criticisms levelled at the Blues this season has been their occasional tendency to get dragged out of position in central midfield, with the defensive awareness of Cesc Fabregas at one point meriting its own video analysis from Gary Neville.

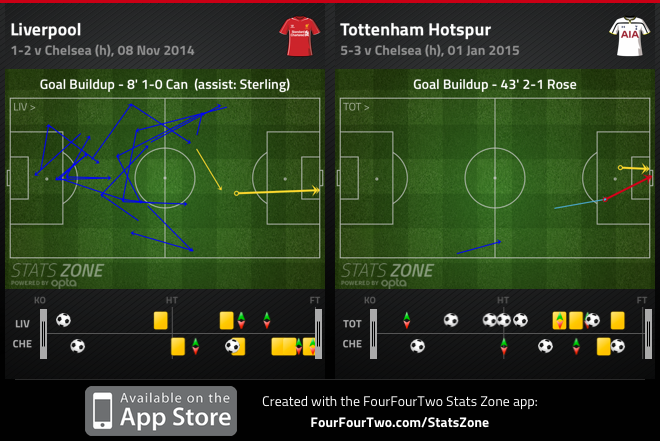

West Londoners may indeed recall Liverpool’s opener in Chelsea’s 2-1 league win at Anfield in November, when Can struck a deflected 25-yarder without a Blue shirt in sight. Or the second goal conceded in the 5-3 horror show at Tottenham, when Christian Eriksen tiptoed past Nemanja Matic to create the decisive chance.

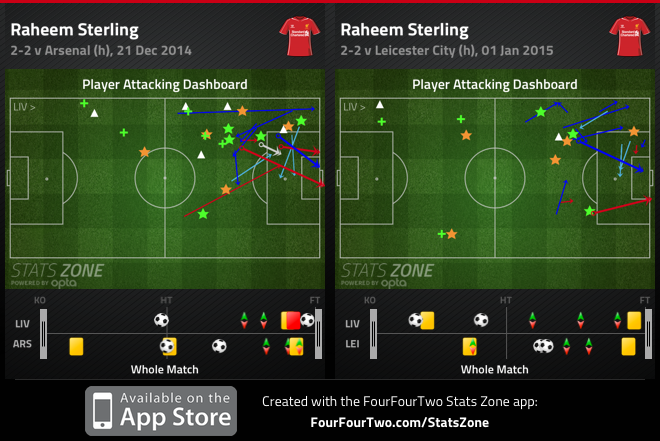

An additional entry in Mourinho’s notebook may plan for the lone striker’s lively movement. If Raheem Sterling plays, the fleet-footed makeshift forward might seek out the left-side channel, from where he takes on defenders and sets up team-mates.

Hazardous habits

But the traits that make Liverpool dangerous also make them vulnerable. Since their positional play in possession is normally so audacious, Chelsea will eye quick breaks and turnovers. The wing-backs can be particularly daring. Rodgers instructs both to track back and support the back three but, when the ball is lost, they might require too much time to recover.

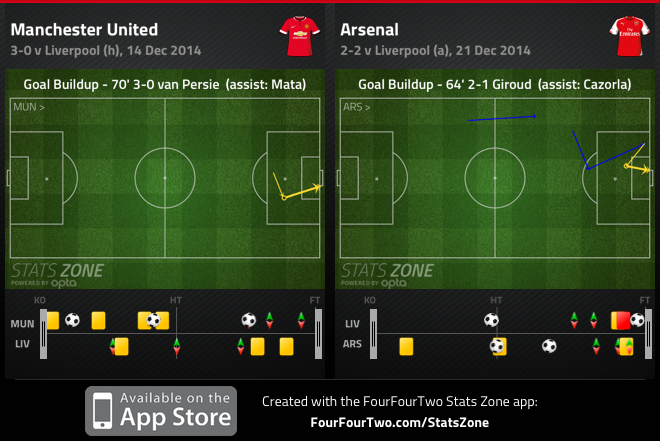

Few exploit such imbalances as Mourinho. In the transitional phase, the Portuguese will try to get men running at an isolated back three, like Manchester United did for their third goal at Old Trafford in December.

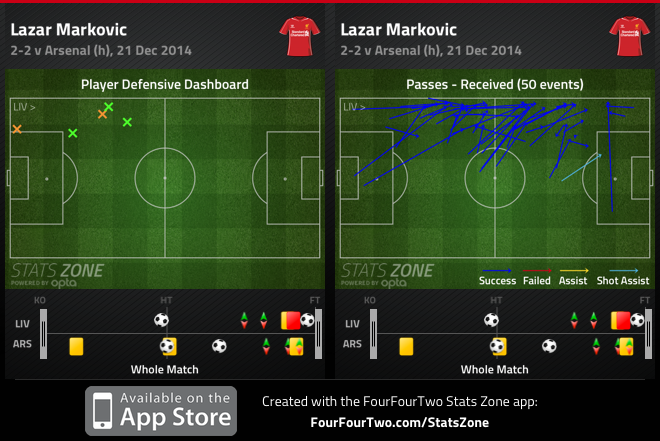

Another aim will be to catch out the wing-backs, either through the full-backs or the wingers, like Arsenal managed in the anarchic 2-2 draw at Anfield before Christmas when Kieran Gibbs motored forward to find Santi Cazorla whose cross set up Olivier Giroud.

There are further incentives in bypassing Liverpool’s wing-backs. Should Chelsea get a clear run at the three-man defence, the outside centre-backs could be drawn wide to close down whoever is carrying possession. This is normally Sakho (left) and Can (right) and, while both are reasonably mobile, neither is likely to be untroubled against a classy winger.

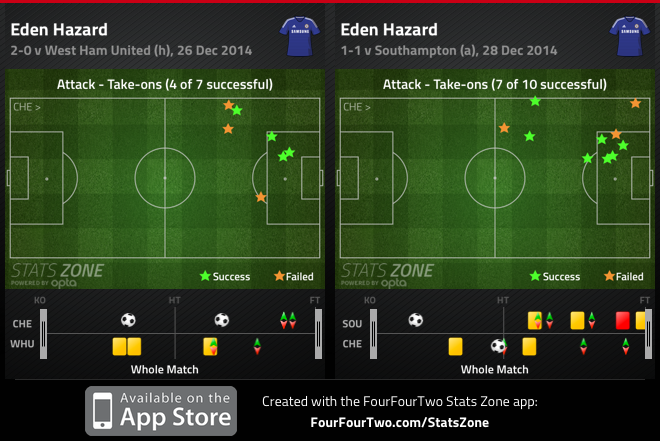

Incidentally, Chelsea do have one of those. Eden Hazard is the Premier League’s top dribbler by considerable distance, and specialises in taking on defenders down the left.

Squares and triangles

Depending on the defensive setup Rodgers selects, Chelsea might also enjoy numerical superiority in the centre. This appears contradictory to the aforementioned point of Liverpool’s midfield ‘square’, but their shape can change when without possession.

Rodgers often asks his two playmakers to track back in wide positions, so that the wing-backs can focus on the wingers. (Indeed, if he didn't, the opposition full-backs would either go unchecked, or the outside centre-backs would need to mark the wingers.)

This would give Chelsea a three-versus-two situation down the middle. It would not be without risk. If Mourinho fields his strongest line-up, the triumvirate of Oscar, Matic and Fabregas could orchestrate venomous moves, exchanging neat passes between the lines before setting up advanced players. They controlled this zone expertly against Swansea, with chances and goals fashioned through intricate interplay.

These talking points set the scene for a showdown sure to work the brains of tactically-minded observers. The managers will be aware of the formational clashes, and a key aspect will be to shuffle players across to the relevant zones to retain balance and compensate for numerical disadvantages. With so many variations and variables in effect, this could be an occasion where strategy proves particularly crucial.