Why Cruyff matters

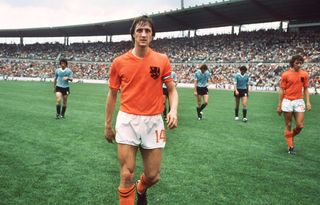

Football's greatest revolutionary has gone. Andrew Murray discusses what the Dutchman meant to himself and many others…

I’ll never forget where I was when I found out my Gran died. She’d been ill and when I heard my phone ring from my bedside and saw it was my mum, one Saturday morning at 8am earlier this year, I knew what the call would be about.

Earlier this afternoon, I saw a Tweet that drove a dagger to my heart. Johan Cruyff, my hero, my ultimate football love had died. From now on, I’ll never forget the seat at which I was sat when I saw the news. Gutted doesn’t quite cover it.

A true great

Cruyff may sit below Pele and Diego Maradona in ‘the greatest ever’ lists, but his legacy extends beyond his playing days. He had a football conscience, he cared about the game, how it should be played and its future. The beautiful game was exactly that to Cruyff – something to cherish and pour over, like a Picasso painting or a Mozart symphony.

As a roaming centre-forward, Cruyff was the epitome of Ajax’s Total Football approach in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. Under Rinus Michels, Cruyff went where he saw fit, causing havoc wherever he strode. It was successful, too, winning six Eredivisie titles in eight seasons from 1965-66 and a hat-trick of European Cups in 1970, 1971 and 1972.

Put simply, he revolutionised the club. Twice – as both player and manager – and remains El Salvador in Catalonia: the Saviour

From there came his other great footballing love: Barcelona. Put simply, he revolutionised the club. Twice – as both player and manager – and remains El Salvador in Catalonia: the Saviour. He won the league in his first season and turned los Blaugranas into European icons. It was during that 1973-74 campaign that he scored ‘el gol imposible’ against Atletico Madrid, his most famous as a player.

Running at full speed to meet a cross from the right wing, the Dutchman sprang into midair and backheel volleyed a goal of never-before-seen beauty. Or since.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

For the Dutch national team, it was no different. The Netherlands may not have won the 1974 World Cup, but they lit up the tournament like no other. They made beautiful football look supremely easy. The way they make you feel stays with you, not the fact they lost in the final.

Lasting legacy

He is so revered because of the imprint his years coaching Ajax and Barcelona have left on football. Frank Rijkaard, Marco van Basten and Dennis Bergkamp all came through under Cruyff

Cruyff was cool. He had rock star long hair and was well aware of his own brilliance. “Before I make a mistake,” he once said, “I do not make that mistake.”

He was notoriously spiky with the media, famously once saying: “If I wanted you to understand, I would’ve explained it better.”

Cruyff’s story, however, didn’t end when he hung up his boots. He is so revered because of the imprint his years coaching Ajax and Barcelona have left on football. Frank Rijkaard, Marco van Basten and Dennis Bergkamp all came through under Cruyff’s gaze.

When he returned to Camp Nou in the summer of 1988, the club was in mutiny, after the players had demanded President Josep Lluis Nunez’s resignation.

Through sheer force of personality, Cruyff turned the club around, winning four successive Ligas from 1990-91 and the 1992 European Cup with what became known as the Dream Team. Yet again, it was about more than victory.

“Salid y disfrutad,” he told his players before that final against Sampdoria at Wembley. “Go out there and enjoy yourselves.” The 1-0 win that followed, thanks to a Ronald Koeman extra-time free-kick, was so seismic, it infected Catalan culture and was seen as a victory for the region.

Shaping the modern game

His revolution extended further than the first team, too. Cruyff trusted in La Masia – abandoning the so-called ‘Prueba de la muneca’ (Doll’s Trial) whereby youngsters who wouldn’t grow up to be taller than 1.80m (5ft 9in) would be released – and prized talent over physique. Without that single change, Xavi, Andres Iniesta and Lionel Messi would all have been let go.

Cruyff is the biggest influence on our modern football. He changed the way we play and every other coach merely adapts his ideas

“Cruyff is the biggest influence on our modern football,” Xavi tells FFT, who admits he owes his career to Cruyff. “He changed the way we play and every other coach merely adapts his ideas. If we give credit to only one person, it has to be him.

“Afterwards there’s been Van Gaal, Rijkaard, Guardiola, and presidents Joan Laporta and Sandro Rossell who have done a lot, but the idea of Barcelona’s philosophy – the one that has been adapted by the world’s best and has been copied – is Johan Cruyff’s. Those years of philosophy won’t leave Barça.”

Pep Guardiola, plucked from Barcelona B on Cruyff’s expressed request, agrees. “Johan Cruyff painted the chapel,” the future Manchester City manager, who is the modern representation of Cruyff’s methods, once said, “and Barcelona coaches since merely restore or improve it.”

It’s a very basic concept: when you dominate the ball, you move well. You have what the opposition don’t, and therefore they can’t score

Since leaving Barcelona, sacked by president Nunez just before the last home game of the 1995-96 season, Cruyff has been on the board at both Ajax and Barcelona.

His sharp tongue continued to criticise modern football whenever it lost its way, even leaving his position as honorary Barça president after clashing with then-incumbent Rosell in 2010.

He resolved to talk about his philosophy. “It’s a very basic concept: when you dominate the ball, you move well,” Cruyff said.

“You have what the opposition don’t, and therefore they can’t score. The person that moves decides where the ball goes, and if you move well, you can change opponents’ pressure into your advantage because the ball goes where you want it.”

Curtain call

That he has succumbed to lung cancer isn’t much of a surprise. A chain smoker much of his life, he underwent heart bypass surgery in 1991 and replaced cigarettes with lollipops thereafter.

The 1994 title victory became know as ‘the Liga of the Chupa Chups’ because of the rate at which Cruyff got through lollipops on the bench as Barça won 28 of 30 available points to win the league.

“I don’t beg,” he recalled after the surgery. “I just want to smoke less and you can only do that if you don’t ask for cigarettes.”

Cruyff reinvented the concept of football in this country. Today, Barcelona and Spain are the ultimate modern testimonies to his spell as coach.

Tragically, they’ve claimed their victim, surrounded by his family in his adopted hometown of Barcelona, aged 68.

“Cruyff reinvented the concept of football in this country,” Miguel Angel Nadal told FFT in 2014. “Today, Barcelona and Spain are the ultimate modern testimonies to his spell as coach.”

Winning was never football’s end game for this aesthete. The sport had to be played with style. Proof comes in his most famous addition to football: the Cruyff turn.

Against Sweden in the group stage of the 1974 World Cup, Cruyff flummoxed full-back Jan Olsson so completely, so mesmerically – feinting to go one way before dragging the ball back behind to sprint in the opposite direction – that the turn now bears his name.

The score in that game? 0-0. Art triumphed victory. Just as it always did with Hendrik Johannes Cruyff.

He was, essentially, football’s David Bowie. A maverick, a genius, a revolutionary who never accepted conventional, received wisdom, especially when he trusted his own instinct. The outpouring of emotion on social media and the football world is testament to that.

Rest in peace, Johan. Football will never be quite the same again.

Andrew Murray is a freelance journalist, who regularly contributes to both the FourFourTwo magazine and website. Formerly a senior staff writer at FFT and a fluent Spanish speaker, he has interviewed major names such as Virgil van Dijk, Mohamed Salah, Sergio Aguero and Xavi. He was also named PPA New Consumer Journalist of the Year 2015.

‘I had it in my contract when I joined Barcelona from Spurs that I’d wear the No.8 shirt – Bernd Schuster said no, so I took Diego Maradona’s No.10 instead’: Scotland hero recalls replacing Argentinian legend at Barca in 1984

Jack Grealish is struggling at Manchester City and it’s time for both parties to cut their losses