Why do so many footballers end up broke? FourFourTwo investigates...

It’s the unseen epidemic: the game’s young, rich and famous ending up penniless. Alec Fenn investigates how excess, addiction and divorce is leading former millionaires to financial ruin

A footballer who played for three of the game’s biggest clubs sobs after learning he’ll soon be made bankrupt. The chairman of a Premier League outfit sighs, before granting his captain an advance on his wages for the last time following another costly defeat at the roulette table. Inside a court, a player pleads with a judge to reduce his child maintenance payments after frittering away his fortune.

These are not plot lines from an episode of Footballers’ Wives, but real stories unfolding in the private lives of three players currently in English football. Forty per cent of their trade suffer from financial problems during their careers and then in retirement. But when the average annual wage of a Premier League footballer is so vast, how on earth do so many fall upon hard times?

For some, the problems begin with the adrenaline rush of signing their first professional contract. A Liverpool player recently tore open the envelope of his first wage packet and headed straight to a car dealership close to the club’s Melwood training ground. He agreed to buy a brand new Range Rover on finance, only to later find out that he couldn't afford the repayments.

Thankfully, we had a good relationship with the garage in question and they were willing to take the car back

Liverpool were made aware of his mistake and so called in Peter Fairchild, a private client tax adviser who offers financial advice to academy prospects at Premier League and Football League clubs, to sit down with the player. “He got confused between his net and his gross income,” he explains to FourFourTwo. “I had to tell him what he would be earning after the taxman had taken his share. Thankfully, we had a good relationship with the garage in question and they were willing to take the car back.”

Fairchild believes peer pressure plays a big factor in the financial mistakes made by young players. “They see a fleet of shiny cars at the training ground and don’t want to be seen driving a Fiat Punto,” he continues. Former Everton prodigy Danny Cadamarteri made his debut at 17 and had a similar experience across Stanley Park. “I saw wealthy players buying their designer wash bags and new cars and felt I had to keep up with them,” he tells FFT. “It’s easy to get caught up in it all.”

His youthful indulgences seem fairly insignificant compared to a high-profile Premier League star on the books of a London club. The 24-year-old earns a reported £35,000 per week, but he struggles to make ends meet at the end of the month having agreed to pay handsome salaries to family, friends and acquaintances, who carry out a variety of jobs within his entourage.

Bad investments

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

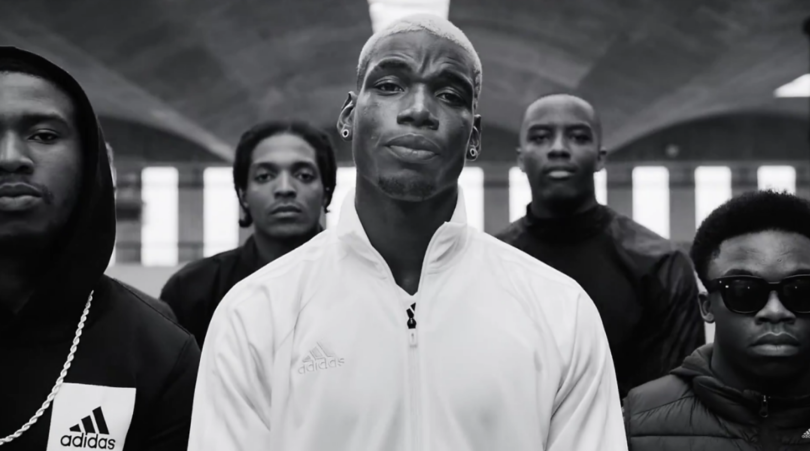

For football’s high rollers, real friends can be hard to find. Agents, financial advisors and businessmen often seek to befriend players before promising to multiply their earnings in return for sizeable investments. “At one stage I had 30 offers from different people in front of me,” the former Manchester United, Everton and Spurs striker Louis Saha tells FFT. “When you’re a player, you don’t have the time to do your research properly and determine who to trust. It’s hard to say: ‘No, I don’t want to invest.’”

The 38-year-old has first-hand experience of being burnt by bad financial advice. A few years ago he was persuaded to invest money in a scheme operated by a UK bank, which promised to recover tax if he invested in certain technology companies. The dividends failed to materialise. “I ended up losing a six-figure sum,” admits Saha. “After that I began to worry about money, I knew I had to be more careful.”

He isn’t the only one to be tempted by lucrative-looking schemes. One Premier League footballer came close to parting with £100,000 in a property development in Morocco that had been recommended to him by a team-mate.

“I told him to look the place up on Google Earth – he didn’t even know where it was,” says Fairchild. “To get there you had to fly to Marrakesh, then get another internal flight, followed by a three-hour drive to the location. I said: ‘How are you going to get your workforce and building materials there for a start?’ He didn’t invest, but others did and lost money.”

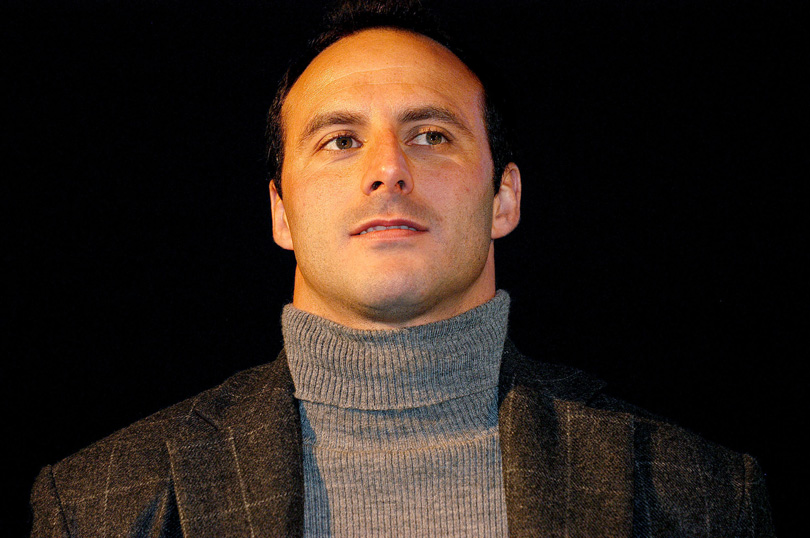

Education is key to achieving long-term prosperity. Former Spurs defender Ramon Vega completed a degree in banking and finance during his formative years as a professional player in Switzerland. Since his retirement in 2004 he has made more than £15m as the founder of London-based firm Vega Swiss Asset Management.

“I was lucky to have a good education in Switzerland,” he tells FFT. “I speak five languages, so I would negotiate rental contracts with UK estate agents for some of my foreign team-mates. Clubs need to give the players financial education.”

They live inside the bubble of an academy, so they’re shocked to hear they might only get half of their wage after tax and national insurance

Some are trying to. Fairchild has visited in excess of 35 teams and provides teenage talents with basic advice to lay the foundations for a sound financial future. “I tell them what they see on their contract isn’t what they’ll see in their bank accounts,” he says. “They live inside the bubble of an academy, so they’re shocked to hear they might only get half of their wage after tax and national insurance contributions.”

He encourages players to split their wages into three pots. “Pot one is for living costs, such as their rent and cars,” he explains. “Pot two is for savings to leave with a trusted advisor to grow – if they put £1,000 a month into some bonds for 18 months, they will have an enhanced sum to put down on a house deposit. Pot three is for spending – they are young and should enjoy themselves.”

But the soundest advice can still fall on deaf ears. The bright lights of casinos and instant gratification of betting apps continue to prove the downfall of players with bulging bank accounts. In his book How Not to be a Football Millionaire, former Manchester United wideman Keith Gillespie revealed that he squandered £7.2m through gambling before being declared bankrupt in 2010.

A study by the Professional Players’ Federation in 2014 found footballers are three times more likely to have gambling issues than the average population

John Hartson narrowly avoided the same fate. He’d racked up over £300,000 in gambling arrears before signing an Individual Voluntary Agreement, which saw him gradually pay back 12p of every £1 owed to a lengthy list of creditors. Michael Chopra and Matthew Etherington also lost sizeable sums before checking into gambling addiction clinics. A study by the Professional Players’ Federation in 2014 found footballers are three times more likely to have gambling issues than the average population, but why?

Doctor Henrietta Bowden-Jones works as a consultant psychiatrist in addictions for the Nightingale Hospital. Among her patients are city bankers and elite sportsmen, and she believes the competitive environment of football dressing rooms, the personality traits of players and even their genetics can make them vulnerable to frittering away all of their fortunes.

“If there is a history of it in the family, then it can get passed down,” she explains to FFT. “Early life events which were serious enough to make a player want to escape them are also common in players with gambling addictions. Then you’ve got a confident individual who believes that he will be successful in predicting the outcomes of sporting events, combined with a surplus of cash – and that’s a dangerous combination of factors.”

Lonely and at risk

Flashing slot machines and the friendly patter of roulette dealers can often provide comfort for players, who are feeling lonely after joining a new club hundreds of miles away from their families and friends. A former Premier League footballer – who did not wish to be named – remembers seeking some refuge in his local bookies.

“I went out on loan to QPR and it was the first time that I’d lived away from home,” he says. “I didn’t know anyone in London, so I started betting to kill some time after training.”

Boredom is an excuse that Graeme Law heard time and again when he interviewed 34 current and former professional players – including international stars and Premier League regulars as well as those lower down the football pyramid – as part of his PhD at the University of Chester. “Players choose to gamble as a way to relieve boredom on journeys to away matches and after training sessions on pre-season tours,” he says.

One player told him he found the buzz of online poker more thrilling than playing football matches. Another admitted that the entertainment of the FIFA video game tournament that’d be staged on the team coach, in which sizeable sums were bet on each virtual game, sometimes surpassed the pleasure of the real-life contest.

Players choose to gamble as a way to relieve boredom

Several players said their performances had suffered after losing thousands of pounds during gambling sessions on the team bus. Many footballers have also lost vast sums of money investing in property. That includes ex-Aston Villa and England midfielder Lee Hendrie, who was declared bankrupt in 2012. But he wasn’t just blowing his money at the bookies.

“Obviously people can paint a picture of you – ‘he’s done all his money’ – but I have never put myself in that situation where I’ve been a gambler,” Hendrie said in a 2015 interview. “I like to go out and have a bit of fun, which everyone does, but unfortunately my properties just didn’t work and it all fell on top of me. The market crashed – I couldn’t sell my house.”

Hendrie later admitted that his financial woes were a factor in him twice trying to take his own life. “It all just got too much,” he said.

Life changes rapidly for players following retirement and, amazingly, 33 per cent of ex-pros are divorced within 12 months of hanging up their boots. A large proportion leave their marriages with their own wealth severely compromised. In 2004, a court ruled Ray Parlour had to pay his ex-wife, Karen, £440,000 every year – more than a third of his £1.2m-a-year salary with Arsenal – and he also had to provide two mortgage-free houses valued at £1m and a lump sum of £250,000.

Sam Hall, the founding partner of family law firm Hall and Brown, recently represented Celtic’s manager Brendan Rodgers in divorce proceedings with his ex-wife. Hall is the man many footballers turn to in a bid to limit the damage to their wealth. With settlements starting at 50-50 between husband and wife – before maintenance payments for children are discussed – his task is to lower that split to the player’s advantage as much as possible.

“When judges see a player earning £100,000 a week, they assume they will have a high income for their entire career,” he tells FFT, “but they’ve got a shelf life of about eight years at the top of their earnings. This could be cut down with one bad tackle, after which he can’t earn anymore. Normal people work for 40-45 years and have the chance to restock the pot after a divorce. Footballers’ wages plummet after they stop playing and very few are high earners beyond their 30s.”

Professional contraception

Upon divorce, the courts can order footballers to switch a host of assets over to their wives, including property at home and abroad, as well as savings and pensions. They can even demand businesses are sold – with some or even all of the profits handed over – while maintenance payments for children and their spouse may be set over a definitive timeframe or, in the worst case scenario, the rest of a player’s life. Hall urges them to use what he calls ‘professional contraception’ to protect their assets.

His biggest mistake had been to appoint his former boot boy as his agent and then put him in charge of all of his assets

Renting, rather than buying, properties and maintaining separate financial lives through sole name bank accounts are just two ways players can minimise the liability to their finances. However, neither provides cast-iron protection in divorce courts and even pre-nuptial agreements – although influential – can sometimes be overruled by a judge. “Not only do we have the most lucrative divorce culture in the world in England and Wales, but we’ve also got no mechanism to safeguard against it,” explains Hall.

The protection of footballers’ wives in UK courts has alarmed many foreign players arriving in England from European teams, as they’re often accustomed to a system which protects their assets through binding pre-nups. January is one of Hall’s most chaotic months. He routinely answers the phone to the representatives of players from overseas, wishing to draft up pre-marital contracts to protect their riches prior to signing for the new club.

One player recently pleaded with a judge to scale down his child maintenance payments from £95,000 a year to just £65 per week after falling into financial disarray. His biggest mistake had been to appoint his former boot boy as his agent and then put him in charge of all of his assets. “Agents always need to be regulated, otherwise players could be exploited,” insists Hall. One leading British player has risked falling into the same trap, after hiring a representative whose previous experience involved being in charge of a company selling advertisements onto beer mats.

Louis Saha is trying to protect players from placing their trust in the wrong people. In 2014, he launched Axis Stars – a social network that allows footballers to discuss lifestyle, insurance, finance, sponsorship and other career-focused matters with fellow pros, as well as contact trusted experts in those fields. They’re also able to use a contractual management platform, which lets them view their relevant financial documents in one place. “I want to make sure that players don’t get conned and lose their money,” he says.

However, there is little that the Frenchman’s venture will be able to do to halt the looming financial iceberg for hundreds of current and retired professionals.

Before 2010, a host of footballers had profited from Employee Benefit Trusts. Clubs paid large sums of money into them, which were then transferred to their players as tax-free loans to top up the salaries. But a change in the law will see individuals who have received but not yet repaid the loans by April 2019 ordered to pay income tax on the remaining amounts.

The ruling will affect players who have taken out loans since 1999 – this means those who’ve long since retired, as well as current pros, could end up with huge tax bills they cannot afford to pay back, resulting in widespread bankruptcies. “If they'd received £2m, for example, they’ll have to pay 40-45 per cent of that figure to the taxman, who will only accept cash,” says leading tax expert Andy Dodd. “If I was a footballer who had received one of the loans and not paid it back, I would be very, very concerned.”

Their bank managers should be, too.

Illustrations by Joe Waldron. This feature originally appeared in the May 2017 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe!