Why Jose Mourinho is destined to fail at Manchester United

Mourinho may be a great manager, but he's struggling against his own instincts to create an attacking side at Old Trafford, as Thore Haugstad explains

When Jose Mourinho was in his early teens in Portugal, his first serious football assignments were to scout opponents for teams managed by his dad.

The reports were good. Once, when Felix Mourinho’s side needed a draw to secure a promotion play-off place in the second division, Jose spied on their opponents for a week, compiling information that helped earn a 0-0 draw. “He knew everything,” said Felix.

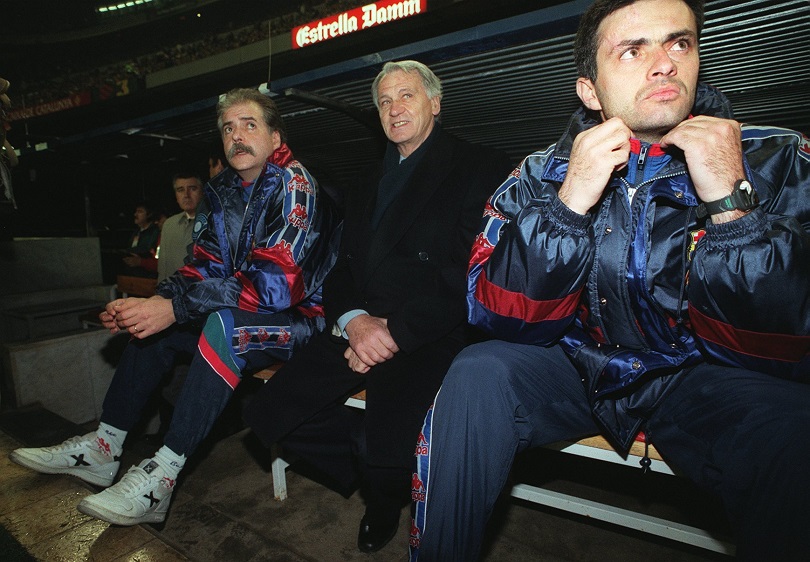

When Mourinho later graduated from translator to assistant coach under Sir Bobby Robson, his boss would drill the team in the final third, leaving the Portuguese responsible for the defence. Coupled with his scouting experience, this nurtured his speciality: to analyse the threats of the opponent and organise his team accordingly.

This ability to nullify rivals would underpin his successful career. But now, in this new chapter at Manchester United, the challenge to build a more attacking side has required skills he does not seem to possess.

The United way

While it has been an improvement on the drab Louis van Gaal years, it is still miles away from the exhilarating football seen under Sir Alex Ferguson

The facts are well known. United have this season's second-best points average on the road, where teams cede more space, but nine home draws have made a top-four spot unlikely. They have deserved to win the majority of those stalemates, but succumbed to bad luck and wastefulness. Indeed, they have fired the second-most shots per game from inside the box at home, but scored only the 14th-most goals.

That said, their attacking play could also have been better. United have often been stale and lacked cohesion, particularly in the final third, and while it has been an improvement on the drab Louis van Gaal years, it is still miles away from the exhilarating football seen under Sir Alex Ferguson.

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

All along Mourinho has vowed to follow United’s attacking tradition. He has emphasised how they have to entertain and, when points have escaped, he has highlighted their style. The “dominancy, the quality, the beauty of our football” is what has pleased him the most.

Interestingly, this is the exact opposite of what he did in his early years, when winning was everything and style was deemed irrelevant. He built cautious, counter-attacking teams because that’s what he did best. The fact that the United project obliges him to do otherwise compromises his ability to get results.

Winning at all costs

His finest sides were his early ones: Porto, Chelsea and Inter were robust, mechanical, cynical, disciplined

Indeed, his greatest nights have come at clubs who cared little for style. At Porto, nobody was bored when he won successive league titles and the Champions League. At Chelsea, Roman Abramovich’s initial priority was to win. At Inter, Mourinho revelled in the Italian win-at-all-costs mentality, delivering a treble that ranks as his finest achievement.

Conversely, at Real Madrid, his pragmatic nature made him an awkward fit, and he struggled. Back at Chelsea, where Abramovich now wanted a clear ‘identity’, he tried to adapt by signing Cesc Fabregas, but reverted to type halfway through the second season as the Blues won the title.

No doubt, his finest sides were his early ones. Porto, Chelsea and Inter were robust, mechanical, cynical, disciplined. They would stop the opponent, then score from a counter-attack, a set play, a mistake oe a piece of individual skill. The football could be claustrophobic - but it succeeded.

Crucially, Mourinho designed these teams to capitalise on what he knew best: nullifying the opponent. Keep a clean sheet, and a goal would always arrive.

New preferences

That [pragmatism] is not something that the fans and owners want, that is not something I want for this project so we are going in a different direction and we are not going to change

More recently, since moving away from this formula, Mourinho has spoken as if he still believes it's the most successful way. “If I want to win 1-0, I think I can, as I think it’s one of the easiest things in football,” he said after a defeat by Sunderland in 2014. This season he has predicted Chelsea as champions, because they “defend a lot” and play on the break – just like he once used to.

Likewise, the requirements at United have modified old preferences. He sold Juan Mata at Chelsea, but now values him for his creativity. There are fewer counter-attacks. For the first time, he's playing without a ball-winning holding midfielder, instead using the 35-year-old Michael Carrick.

“We are not a team that defends and waits for an opponent’s mistake,” Mourinho said in December. “I know [how] to build these teams, I did before. Being very pragmatic, that was not our choice. That is not something that Manchester United fans and owners want, that is not something I want for this project so we are going in a different direction and we are not going to change.”

Yet this surely emphasises his weakness rather than his strength. Long before United, many of his teams laboured against established defences, because he's not great at coaching this. They would lack rhythm, ideas, a clear plan.

To compensate, they would have at least one midfielder capable of creating things on his own: Deco, Frank Lampard, Wesley Sneijder, Mesut Ozil, Eden Hazard. When the collective failed, individuals took charge.

The same applied, and still does, to his best strikers. As late as Sunday, when United were creating nothing at Sunderland, Zlatan Ibrahimovic scored a goal out of nowhere.

Stylistic compromise

This means that the United project is at odds with the coaching profile Mourinho has built. A manager specialising in counter-attacking football is trying to build an entertaining, possession-based side in the tradition of Ferguson.

Had Mourinho fully mastered this dimension, his former teams would surely have been far better at breaking down established defences than they were. To take one example, Chelsea never scored more than 73 league goals in any of his five full seasons. By comparison, the Chelsea side that won the title under Carlo Ancelotti hit 103, while that of Antonio Conte are on course for 80.

As such, United have in some ways been as expected. They have the second-best defensive record, showing Mourinho hasn't lost his touch, but have scored just 46 goals in 30 games, which may be harsh but still denotes a passing game that leaves much to be desired.

Only time will tell if Mourinho can develop the required attacking blueprint, but what seems certain is that as long as the stylistic demands persist, he is unlikely to be as successful at United as he potentially could be.