Why the Milan clubs just aren't what they used to be

Ahead of Sunday's Milan derby at the San Siro, Greg Lea assesses where it all went wrong for two of Italy's most famous clubs...

There are many cities that could legitimately claim to be the football capital of the world. Manchester, Madrid, Lisbon and Sao Paulo are all home to more than one major club, Buenos Aires hosts an incredible 24 outfits, while Istanbul is well known for the intense passion and fervour of its football followers.

Serie A: 2010/11

Coppa Italia: 2002/03

Champions League: 2006/07

2013/14 league finish: 8th

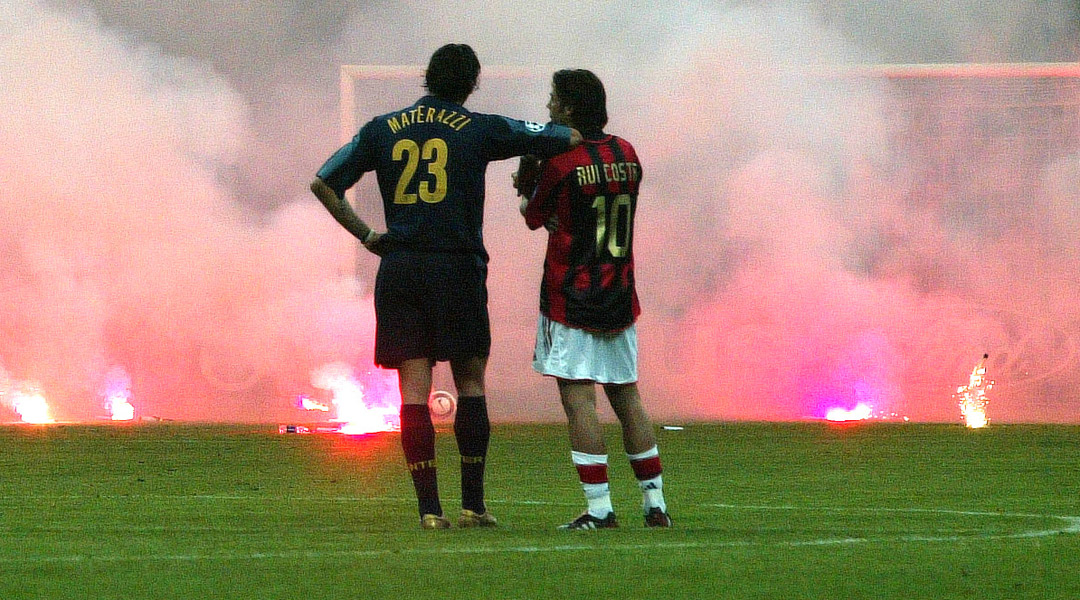

In terms of success and trophies won, however, there is no rival to Milan. Between them, Internazionale and AC Milan have won 36 Scudetti, 12 Coppa Italias, 10 Champions Leagues, five UEFA Super Cups, five Intercontinental Cups, three UEFA Cups and two Club World Cups. A trip to the pair’s shared museum at San Siro is like walking into an oversized treasure chest.

As Inter and Milan prepare to meet in the derby this Sunday, though, both sides find themselves in an unfamiliar position. Neither are in the Champions League – a continuation of last season, which was the first time Italy’s second city was not represented since 2001/02 – and both are already out of the title race after 11 games. Most damningly of all, nobody ever expected either of them to be in it.

Serie A: 2009/10

Coppa Italia: 2010/11

Champions League: 2009/10

2013/14 league finish: 5th

Down with a thud

It is easy to forget that just five seasons have passed since Inter looked down from the top of the global game. Jose Mourinho guided the Nerazzurri to an unprecedented treble in 2009/10, with a team featuring Wesley Sniejder, Samuel Eto’o and Diego Milito dominating on all fronts.

It is slightly longer since Milan’s high point of recent years, but their decline has been just as stark.

The Rossoneri, led by Paolo Maldini, Andrea Pirlo, Kaka and Andriy Shevchenko, reached three of five Champions League finals between 2003 and 2007, winning two and losing one on penalties in a certain 2005 match in Turkey.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Things are different now. Going into this weekend’s Derby della Madonnina, Milan sit seventh and Inter ninth in Italy’s top flight, having won just eight of 22 games between them. The giants are not yet fully asleep, but they have certainly been dozing.

In some ways, Milan and Inter are victims of calcio’s general malaise: the days of Serie A being the pinnacle of European football are long gone. It is telling that talk of UEFA co-efficients on the peninsula involves Italians nervously looking over their shoulder at Portugal and France, rather than considering how Spain, Germany and England can be caught.

The wider economic downturn has had a profound effect. Milan’s cost-cutting saw Zlatan Ibrahimovic and Thiago Silva – perhaps the world’s best centre-forward and centre-half – sold to Paris Saint-Germain in 2012 as wage bills were slashed up and down the country. Inter, too, were gradually forced to move on many members of their treble-winning squad: Eto’o and Marco Materazzi departed in the summer of 2011, Lucio and Thiago Motta followed a year later and Sneijder joined Galatasary in 2013 after making only 50 league appearances in the three seasons post-Mourinho.

It is telling that talk of UEFA co-efficients on the peninsula involves Italians nervously looking over their shoulder at Portugal and France

Structural revisions, such as the move from an individually to collectively bargained TV deal, have also had an impact. Under the previous arrangement, Milan and Inter’s rights would sell for almost €150 million, while the league’s smaller clubs earned as little as 15 times less. The playing field has not quite been levelled, but there is much greater equality today.

Crowds across Italy are relatively low, a combination of antiquated stadia (largely a consequence of excessive bureaucracy at the level of local government), decreased quality of product and the threat of terrace violence driving people away and impacting heavily on a vital revenue stream.

It is difficult to hold Milan and Inter solely responsible for such a situation, just as they cannot be blamed for the entire country’s inability, until recently, to attract the foreign investment that has stimulated other leagues across Europe, nor the chronic underdevelopment of Serie A’s international commercial links. Nevertheless, they have undoubtedly been damaged by such conditions.

Too much, too fast

Some of today’s problems, however, are entirely of the clubs’ own making. Inter have employed six managers since Mourinho’s departure in 2010, recently-sacked Walter Mazzarri the longest-serving after a year-and-a-half at the helm. Gian Piero Gasperini was hired in June 2011 and dismissed in September, while his successor Claudio Ranieri spent just six months in the dugout.

Italian outfits have never been known for their patience, but such a lack of managerial continuity has visibly harmed Inter, who have jerked from one playing style to the next with no sense of an overriding strategy. Milan, too, have been impaired by a lack of cohesion, with key boardroom figures Adriano Galliani and Barbara Berlusconi – daughter of owner Silvio – spending much of last season publically bickering about the direction the club should take.

Neither club has adequately replaced recently-departed long-serving legends, either. Milan’s Clarence Seedorf, Alessandro Nesta, Gennaro Gattuso and Pippo Inzaghi all retired or moved on in 2012, while Inter’s veteran quartet of Javier Zanetti, Walter Samuel, Esteban Cambiasso and Diego Milito did the same last summer. The loss of such stalwarts has left both looking lost and lacking a defined identity. It is their personalities as much as their footballing abilities that are missed.

The most disappointing thing about the current woes of the Milanese is that much of it could have been prevented. The reactive style of leadership has been costly. Both clubs knew for years that the above players were ageing, yet a lack of foresight meant there were no ready-made replacements poised to step in.

It is of course difficult to replace players of such calibre – the eight lynchpins won 573 international caps between them – but neither Milan nor Inter seemed to have anything resembling a succession plan. The latter have been particularly guilty of neglecting youth development: since 2010, Marco Andreolli, Joel Obi and Marco Faraoni are the only academy products to have played more than 10 Serie A games for the Nerazzurri, and none of the trio have ever been regular first-team starters.

The most disappointing thing about the current woes of the Milanese is that much of it could have been prevented

The future of San Siro also remains unresolved. As Juventus and Roma built or produced concrete plans for privately-owned grounds, Milan and Inter carried on as normal.

Change has only been seriously discussed in the last few months, with money tighter and attendances lower than days gone by.

It is true that building a new home in Italy is never easy, but the duo’s lack of providence has been astounding.

The latest Deloitte Football Money League report – which analyses the 2012/13 campaign – shows that Juventus earned €18.6 million more from their stadium than Inter and €11.6 million more than Milan, despite the Bianconeri’s arena housing 40,000 fewer people. That gap is only widening year on year. Milan and Inter should have long since acted.

Enter Erick

It is interesting that the sides have taken slightly different approaches in their attempts to return to the upper echelons of Italian football. Inter, the nominal away team on Sunday, were taken over last year by Indonesian businessman Erick Thohir, who has targeted opening new sources of income in emerging football markets around the globe.

The latest Deloitte report shows that Juventus earned €18.6 million more from their stadium than Inter and €11.6 million more than Milan

Thohir inherited coach Mazzarri and initially demonstrated considerable restraint despite some underwhelming performances and results. The new owner likely recognised Mazzarri’s vast experience and was prepared to give the 53-year-old as much of a chance as possible because of it, but a tepid 2-2 home draw with Verona was the final straw. Again, though, the replacement of Mazzarri with Roberto Mancini – who bossed Inter between 2004 and 2008 – shows a preference for experience and proven knowhow.

After last term’s fifth-place finish, Inter were expected to push on and challenge for the top three this season. Supporters were hopeful after what was widely perceived to have been a positive summer transfer window, with Gary Medel, Nemanja Vidic and Dani Osvaldo joining a squad that already contained the promising Mauro Icardi and Mateo Kovacic, and the talented Hernanes and Rodrigo Palacio. Mancini will still hope to achieve that objective, but the Nerazzurri’s start to the campaign has been marked by mediocrity.

Over on the red side of the city, Milan’s executive setup remains much the same. Silvio Berlusconi announced his intention to gradually make the club financially self-sufficient back in 2012, and a glance at some of the names currently on the Rossoneri’s books is evidence of that process. Keisuke Honda, Nigel de Jong and Stephan El Shaarawy are all excellent players who have begun the season well, but Milan’s current playing staff pales in comparison with teams of the past.

In the dugout, Milan have taken a different path to their local rivals. Max Allegri was sacked in January and replaced by Seedorf, a managerial novice who was still playing for Botafogo in Brazil. The Dutchman lifted Milan from 11th to 8th but clearly did not do enough to impress and was replaced by Pippo Inzaghi in the summer. With two seasons coaching Milan’s Primavera under his belt, Inzaghi is not a total rookie, but Berlusconi’s present predilection for a younger man is clear.

Four years ago, Milan won a November derby against Inter, an Ibrahimovic penalty securing a 1-0 win for a side that also contained Silva, Nesta, Pirlo and Gianluca Zambrotta. Milan would go on to win the league a few months later, while Inter, whose employees included Zanetti, Eto’o, Sneijder, Lucio and Milito, had to settle for second place and the Coppa Italia.

Sunday’s list of potential protagonists includes Sulley Muntari, Zdravko Kuzmanovic and a fading Fernando Torres. The Derby della Madonnina has clearly lost much of its stardust. If Milan hopes to reaffirm its position as football capital of the world, it needs to get it back quickly.

Greg Lea is a freelance football journalist who's filled in wherever FourFourTwo needs him since 2014. He became a Crystal Palace fan after watching a 1-0 loss to Port Vale in 1998, and once got on the scoresheet in a primary school game against Wilfried Zaha's Whitehorse Manor (an own goal in an 8-0 defeat).