Why players, not fans, must take the lead against homophobia

Rainbow laces aren't enough, says Chas Newkey-Burden – football won't change until players speak out… or come out

I’d read about them in an Arsenal fanzine. It said they gathered in a pub near Highbury before home games. I joined them a couple of times during the 1994/95 season. We’d stand, maybe half a dozen of us, among our fellow Arsenal fans, hoping they wouldn’t discover our terrible secret – that we were the ‘Gay Gooners’.

Fast-forward 20 years and the Gay Gooners are out of the shadows. A banner celebrating their now-thriving group hangs at Emirates Stadium and the club promotes their activities on social networks. Arsene Wenger speaks empathically about gay players, and Arsenal first-teamers have starred in a witty anti-homophobia video.

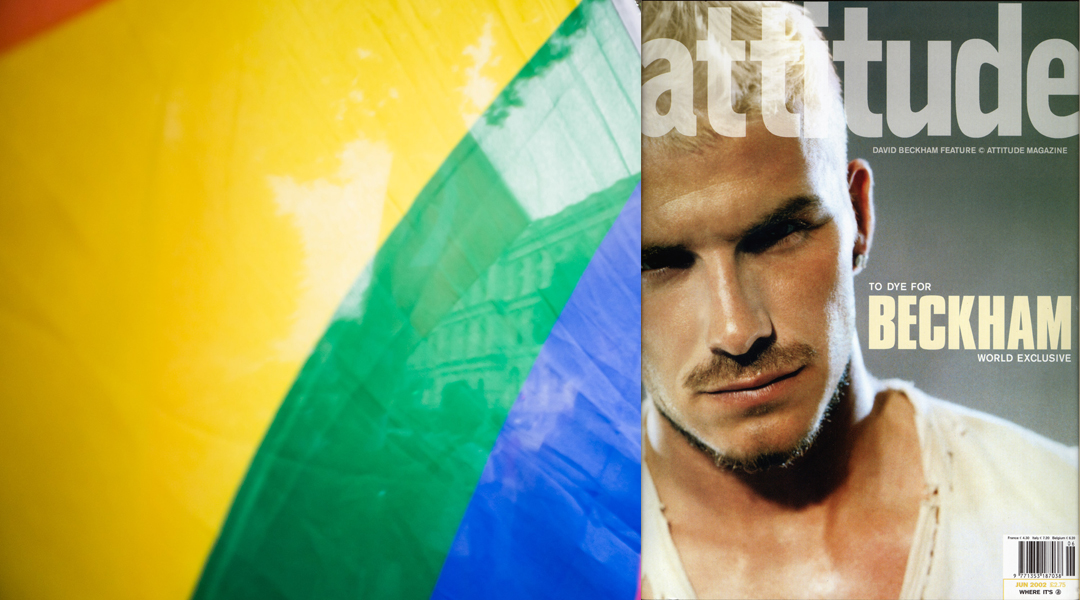

Support for gay issues, once the preserve of fashionistas David Beckham and Freddie Ljungberg and soapbox-botherer Joey Barton, is spreading among professionals. This weekend, many will tie their boots with #rainbowlaces, to support an anti-homophobia campaign.

So we’re done? Homophobia has been kicked out of football and we can bask in a now cosmopolitan beautiful game?

Grass-roots grief

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Not so fast. Beyond the world of media-savvy top-flight stars, things are different. Sunday morning football remains hostile territory. Gareth David, who plays in the Bath and North Somerset District Sunday league, recently faced a barrage of homophobic remarks after he complained about a casual anti-gay insult used by an opposition player.

Gareth, who isn’t gay, told me has nevertheless noticed that attitudes to homosexuality are “absolutely backwards” in the Sunday league, which is “light years away” from being an environment able to embrace openly gay players. “It would be completely alien,” he says.

He predicts that some players in his league will be wearing rainbow laces this weekend, but suspects that these may be the same guys who describe white football boots as “gay” and shout “faggot” if someone delivers a poor cross.

Rainbow laces? It’s not helping people to change their views, it’s telling people not to express their views"

Although he’s supportive of gay rights, Gareth won’t be wearing rainbow laces. He believes the campaign is gimmicky, and one of repression rather than education. “It’s not helping people to change their views, it’s telling people not to express their views, which only entrenches them,” he said.

London-based social media director Peter Wood also feels the campaign could have been better focused. Peter, who faced “disgusting vitriol” when he wrote in admiration of the Gay Gooners on his popular football blog Le Grove, says it should not be rainbow laces the players wear but rainbow armbands. “When someone in the game dies, the players wear black armbands, because it’s prominent,” he said. “This campaign should be bigger than laces because homophobia in football is a massive problem.”

It's a problem that echoes in football stands throughout the country. In my experience the trend spans generations: players who fall to the ground when tackled are routinely denounced as “poofs” by older men, while a poor shot at goal will be described as “so gay” by younger fans.

And it’s not just at the fabled ‘[insert Northern town] on a freezing Tuesday night’ that this happens. Even among Arsenal fans, the enlightened club in the heart of liberal Islington, homophobic chanting is heard. A Gunners fan told me he was “really, really sad” when fellow supporters chanted anti-gay songs at Brighton fans last year. “It’s not just ‘banter’,” he said, “it’s implying that if you’re gay you shouldn’t be at football, that there’s something wrong with you, that it’s OK to laugh at you.”

Liberal players, conservative fans

Yet in my experience this prejudice is not matched among professional players. Between 2000 and 2002, I was the official personal ghostwriter for half a dozen stars, including Dennis Bergkamp and Paolo Di Canio. It was a close working relationship: we spoke on the phone a few times a week, met a couple of times a month, whizzed up and down motorways in their fast cars.

I'd happily celebrate goals with a gay player and shower in the same room as him”

My sexuality was never an issue. One day, I asked one of the players whether he could ever accept an openly gay team-mate. He said it would be no problem for him or any of his fellow players. “Yes, I would happily celebrate goals with him and shower in the same room as him,” he said. “Not a problem at all.” Wouldn’t you worry he might look at you in the shower, I asked? “I’d only worry if he wasn’t looking,” he replied. But when I asked if I could quote him directly on this, he said: “Best not to.”

David Beckham, however, has always gone on the record on gay matters, as I encountered personally in 2006. That spring, FourFourTwo published a lengthy feature I’d written about homophobia in the game. At the time it was published, I had been trying for months to get an interview with Beckham for The Big Issue’s World Cup edition. Suddenly, Beckham’s agent agreed to my overtures, telling me that Becks himself had read the FourFourTwo feature and wanted it to be known that he admired my stance.

In the years since that conversation, the game has become even more gay-friendly, with Thomas Hitzlsperger feeling able to come out after he retired. The ball is now in the court of gay professionals to really drive the progress onwards by coming out during their career.

The belief that a gay player will come out once the atmosphere has improved gets it the wrong way round: it is only once a gay player comes out that things will really improve. It would take a bit of courage, for sure. But it’s courage, not comfort that makes the world a better place.

One in 10 people are estimated to be gay, so every squad in the league probably includes at least one gay player. Cowering in the shadows only encourages the stereotype of the weak gay man. It’s now time for these players to show that gay men have balls, too. Talk to us, guys.