Why the Premier League Hall of Fame feels wrong

The idea of the new Hall of Fame may seem like a good idea on the surface - but it ignores history and neglects the existing National Football Museum

What would the Premier League do if American sports didn’t exist? Where would it go for its innovation and ideas, if the option just to imitate wasn't there?

On Thursday, the league launched its Hall of Fame, which will welcome its first two charters members on the 19th March.

From there, who knows? At the moment, all the league is willing to reveal is contained within a sparse press release. We’re yet to learn whether the Hall will be a physical place, whether it will curate artefacts and objects, or whether it will just be a metaphorical Hall – an idea rather than a room, a marketing concept rather than a genuine tribute.

We do know that each inductee will receive their own engraved medallion and have the word of Richard Masters to assure us that "a place in the Premier League Hall of Fame is reserved for the very best”, but it’s difficult to know exactly what that means. Particularly given the non-committing reference to a ‘public vote’, which suggests that the league’s executives really weren’t paying enough attention to what works in America.

A public vote? If the aim is gravitas, elitism, and the kind of ethereal reverence which hangs in the air around Cooperstown, New York or Canton, Ohio – homes of the MLB and NFL Halls of Fame respectively – then creating a popularity contest will hinder that objective from the start.

No, not everything has to involve everybody. Sometimes, exclusion is actually a virtue and while the American equivalents are the height of sporting snobbery, that somehow manages to be among their great strengths. It is specifically that illuminati-ish quality of the voting process which gives it its authenticity and, most likely, what separates enshrinement from the more mundane honours across those various sports, such as All-Star selection.

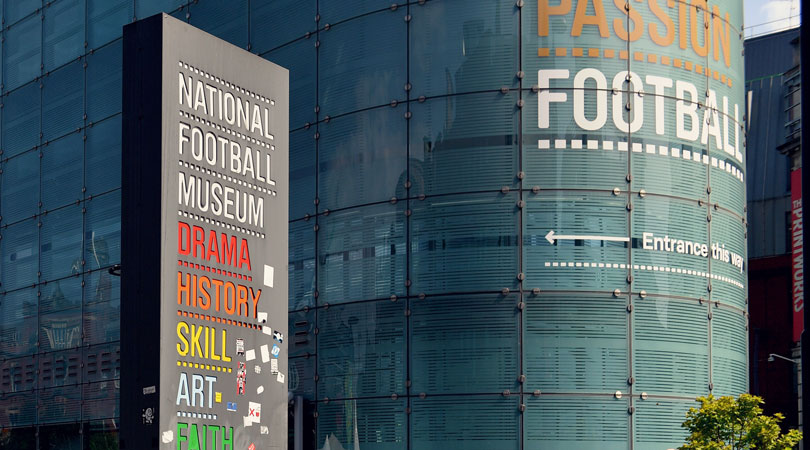

More importantly, though: there is an elephant in the room. English football already has a Hall of Fame. It’s never quite been branded forcefully enough to allow it to properly penetrate the public conscience, but it opened in 2002 and takes the form of a permanent exhibit at the National Football Museum in Manchester.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

The list of inductees is what anyone would expect: it’s the great and good of English football. Duncan Edwards, Bobby Moore, Matt Busby and the rest. Lilly Parr, one of the munitions factory pioneers of women’s football. The great Hugh McIlvanney is there, so too Jack Taylor, the referee who take charge of the 1974 World Cup Final.

The need for the Premier League to launch its own equivalent, then, is baffling. It also exhibits that proprietorial habit that it shows from time-to-time, in which it lets slip the sincere belief that it really does own the sport. That rather than being an arbitrary dateline, 1992 actually was football's Big Bang moment – the point at which everything began to exist and before which nothing else mattered.

That argument can get tiresome. When used as part of any Against Modern Football movement it can, I’m sure, also become very repetitive. Yes, it’s very easy to take shots at the Premier League and some of us are probably guilty of doing so much too often, but this is one of those instances in which it’s right to pose those questions.

Why could it not throw its weight behind the existing Hall? If the real intention is to honour excellence and achievement – to revere those who have touched the sky – then that’s a conversation which cannot just begin in 1992. The Premier League is its own property, its own product – nobody would deny that and nobody would contest its soaring popularity - but it was constructed on a bedrock of history and culture to which it owes an enormous debt. It may not intend to ignore that, but it so often gives the impression of being oblivious, with this self-celebration being just another instance of such hubris.

Arsenal’s achievements under Arsene Wenger are framed by (and actually echoed in) the work of Herbert Chapman. Celebrating Ian Wright’s career depends, in part, on knowing who Cliff Bastin was. And when Harry Kane’s career is over, it’ll matter all the more because – most likely – he’ll have surpassed Jimmy Greaves’ goalscoring record. Do we understand Raheem Sterling's struggle without knowing what Albert Johanneson and Clyde Best suffered through?

These people have to be together. They stand on each other's shoulders. They contextualise one another's achievements.

It cannot be any other way.

The Americans have it right. They have always been far more diligent in chronicling their sporting past, while English sport has been comparatively laissez-faire. But there are ways of addressing that deficit and this – whatever this, sponsored by Budweiser, actually is – doesn’t feel right at all.

While you’re here, why not take advantage of our brilliant subscribers’ offer? Get the game’s greatest stories and best journalism direct to your door for only £12.25 every three months – less than £3.80 per issue – and you’ll also receive bookazines worth £29.97!

READ MORE...

CITY Why beating Real Madrid was Manchester City's finest European night - and the start of something new

QUIZ Can you name every British team to play in a European final?

Seb Stafford-Bloor is a football writer at Tifo Football and member of the Football Writers' Association. He was formerly a regularly columnist for the FourFourTwo website, covering all aspects of the game, including tactical analysis, reaction pieces, longer-term trends and critiquing the increasingly shady business of football's financial side and authorities' decision-making.