Why the Premier League's failure, not success, means it can attract top-class managers like no other

England's top flight is set to be awash with great managers next season, even if most of the very best players continue to congregate in Spain and Germany. Alex Hess investigates a seemingly contradictory phenomenon...

Just when you thought the standard of English football was at its lowest point for years, along come a spate of arrivals that suggest the exact opposite. Or, to put it another way: if the Premier League is indeed floundering, football’s greatest minds don’t seem to have noticed.

If all goes to plan on Tyneside, next year will see Rafa Benitez, Pep Guardiola and Jurgen Klopp all managing in England’s top flight. Word has it they’ll be joined by Antonio Conte, who’s already announced he’ll be stepping down as Italy boss after Euro 2016, paving the way for a move to Chelsea. And then there’s the small matter of a certain Portuguese mischief-maker, widely touted to fill the increasingly inevitable vacancy at Old Trafford.

These are managers of the highest pedigree. In Champions League terms alone, the quintet have amassed six winners’ medals. Add in domestic league titles and that number exceeds two dozen. Heady times, then, for English football.

Player exodus

This influx of high-end football managers to England is in marked contrast to their playing counterparts, who can’t escape the Premier League quickly enough once they've hit the elite tier of their profession

Except it isn’t. These men may be serial winners, but they are joining losing sides. At Liverpool, Newcastle, Chelsea and both Manchester clubs, the new boss’s first task will be to reverse a process of miserable underachievement. Staggeringly, there is a chance that none of those five will be in the Champions League next season.

This influx of high-end football managers to England is in marked contrast to their playing counterparts, who can’t escape the Premier League quickly enough once they've hit the elite tier of their profession: Cristiano Ronaldo, Gareth Bale, Xabi Alonso, Luis Suarez and Javier Mascherano have all shown they know a glass ceiling when they see one. Before them, it was David Beckham, Michael Owen and Thierry Henry hotfooting it to the continent.

Bale unveiled at the Bernabeu in 2013

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

The trend couldn’t be clearer: the best players don’t think English football is good enough. And that judgment is borne out when Europe’s top sides go toe-to-toe. After last night's cakewalk at the Camp Nou, three of England’s four Champions League contestants have now been eliminated – and eliminated meekly – from Europe's acid-test tournament. Since 2010, England has provided the competition with two finalists; Germany and Spain four each, and the momentum is only going one way.

Lure of the Premier League

Beyond England, the only options that would offer a concrete chance of European and domestic trophies would be Juventus, who are themselves starting to look worryingly like a selling club, and PSG

So why are a group of managers, all of whom could effectively cherry-pick any job in world football, so keen to work for the collection of blundering drunks that are England’s big guns?

For a start, these men do not work for free, and what English football might lack in excellence it sure makes up for in enormous piles of cash. (Guardiola is set to earn at Eastlands somewhere between triple and quadruple the wage he did at Barcelona, while Klopp, Arsene Wenger and Louis van Gaal complete the world’s four best-paid coaches.) But there are reasons beyond money.

Of these, the biggest is structural. At its highest level, European club football is starting to become a league unto itself (albeit, for now, an unofficial one). With only a few possessing enough cash to continually retain their place at the top table, the jobs out there for elite managers are lessening.

Ibrahimovic seals a 9-0 win over Troyes, wrapping up another Ligue 1 title

Guardiola, for instance, has already managed one of Spain’s big two (precluding himself from ever coaching the other) and Bayern Munich. Beyond England, the only options that would offer a concrete chance of European and domestic trophies would be Juventus, who are themselves starting to look worryingly like a selling club, and PSG, who have become victims of their own success in that 38 of their season's fixtures are now irrelevant.

Lowered expectations

Conte, whose former bosses at Juventus would see anything lower than a first-place finish as shameful failure, will merely be tasked with guiding Chelsea back into the top four

Guardiola’s shortage of choices is not unique to him. There’s a reason that, since his dismissal from Chelsea, the speculation over the future of Mourinho – in theory one of the most sought-after managers in the game – has essentially focused around a single club. Nor is it coincidence that by next season, Mourinho, Benitez, Guardiola, Manuel Pellegrini and Carlo Ancelotti will have jointly clocked up four stints managing Real Madrid, four at Chelsea, two at Manchester City and two at Bayern.

Combine a small number of big-paying clubs with a small band of big-name managers – and add an almost wilful lack of imagination in said clubs’ hiring policies – and there’s simply not many permutations.

There’s also the fact that a wildly underperforming side – of which England currently offers a quite resplendent range – may well be a more attractive proposition than a full-blown trophy-hoarder. To use the example of Guardiola again, there are plenty who’ll adjudge him to have underachieved at Bayern if he doesn’t win the Champions League this year, despite a probable tally of seven trophies in three seasons.

There’s even an argument to say that his biggest achievement there so far, the Double win of his debut season, in fact represented a regression on the season before. That would be to hold him to ludicrous standards, of course, but there is an undeniable logic to it. Such are the risks in taking over a treble-winning outfit.

At Manchester City next term, on the other hand, a mere upgrade on this year’s pathetic debacle of a league campaign ought to sate the fans and hierarchy for the time being – and all the better if it’s served alongside some serious progress in the Champions League.

Likewise, Conte, whose former bosses at Juventus would see anything lower than a first-place finish as shameful failure, will merely be tasked with guiding Chelsea back into the top four. The same task awaits at Old Trafford. On Tyneside, Benitez need only evade relegation to be seen as a hero.

Open competition

While the newly democratised Premier League might mean its big fish are no longer untouchable in the way they once were, restoring a Man United or a Chelsea to the top four should hardly be beyond any halfway competent manager

The madcap nature of this season’s edition of the Premier League may well have left pretty much all of the country’s traditional big-hitters with no choice but to look utterly ashamed of themselves, but it’s at least painted a fairly welcoming scene for the guys coming in: with the bar currently set so low, they should have little problem in skipping merrily over it.

And while the newly democratised Premier League might mean its big fish are no longer untouchable in the way they once were, restoring a Manchester United or Chelsea to the top four should hardly be beyond any halfway competent manager.

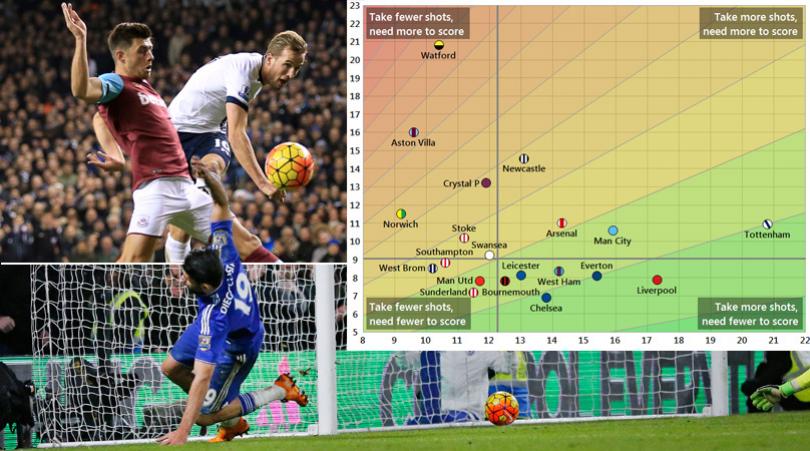

Indeed, the tendency of the best players to flee England may even have in fact fed into this summer’s mass-arrival of top-level bosses. The absence of Ronaldo- or Henry-type superstars has been a large factor in why no major club has been able to elevate itself above the rest of the pack as they have done previously.

Against this new backdrop of shambling hyper-competitiveness (and think: going into next season, it may be right to include six or seven teams in a discussion about title challengers), the Premier League trophy will assume a kind of paradoxical prestige.

A prize worth winning

To a contingent of managers who have come to see a league title as little more than a base-level feat, such a prospect must be inviting – doubly so when it means the season’s success (or failure) doesn’t hinge entirely on the Champions League, with its inherently volatile knockout format.

Just as the towering heights reached by PSG and Bayern have turned Ligue 1 and the Bundesliga into one-horse races and drained them of their kudos, the collective ineptitude of England’s traditional powerhouses will mean the domestic crown is a legitimate cause for dancing in the streets.

It’s a curious way to have gone about attracting the sport’s leading managers, but there you go. In a world where success is prized above all else, it turns out failure comes with major benefits, too.