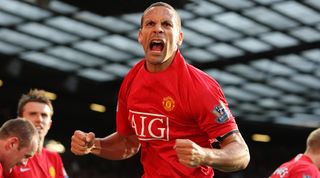

Why is Rio Ferdinand the most unheralded player of his England generation?

The former Manchester United and Leeds defender announced he'd be hanging up his boots for good at the weekend, but Alex Hess says the lack of tributes are peculiar...

Rio Ferdinand has won six league titles, three League Cups, one FA Cup and the Champions League. He has played at two World Cups, won 81 international caps and played at the highest level of English football for two decades. He is a millionaire many times over. At the end of all this, it would seem difficult to paint a portrait of him as a victim of circumstance.

And yet, with the quickening of time, that appears to be exactly what is happening. Last weekend Ferdinand announced his retirement, and his departure drew minimal fanfare. Given his glittering career, the relative absence of tributes to soundtrack its conclusion would have been noticeable regardless, but what made it especially conspicuous is how such praise for his peers has been impossible to escape of late.

Tainted gold

The British public may well have felt spurned by England’s now-infamous Golden Generation back when they were underwhelming at World Cups, but in recent months there has been a sentimental U-turn. Suddenly, English football simply cannot get enough of this collection of heroes. All of them except Ferdinand, that is, who was left to slink into the night to only a smattering of applause. Compare Rio's situation with those of his peers and you'll soon notice that there is something of an injustice at work.

Suddenly, English football simply cannot get enough of this collection of heroes

As the last six months have duly demonstrated, Steven Gerrard, departing deity of the Premier League, has effectively achieved immortality. His six-month farewell tour of the country concluded, quite naturally, with him walking out to a guard of honour and a bespoke 50-foot mosaic spread across a stand full of his worshipping supporters, and the level of reverence for him across all sections of the media since he announced his exit is perhaps without precedent in English football.

Similar tones have been adopted to address the subject of Frank Lampard, the Premier League’s other States-bound statesman. Lampard is slightly different in that his name largely commands a steely respect rather than misty-eyed admiration, but the veneration is there for all to see. After his final Premier League appearance, Lampard was tossed joyously into the air by his Manchester City team-mates, while the column inches detailing his famed focus and work ethic could have filled a Russian novel.

Such affection will always elude John Terry. But Terry conjures a deep respect, however grudging, among British football's punditocracy. And rightly so: his capacity to combine steady success with logic-defying longevity is unmatched by any of his peers. After another season of dogged, trophy-hoisting resilience, the nation's football writers voted Terry the season's third-most impressive performer. His position in British football’s hall of fame is secure, even if little affection exists for him outside of west London.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Look towards the Golden Generation’s peripheries and yet more legacies have been cemented. Ashley Cole’s dependable performances were enough to overcome a litany of bungling PR calamities, with the left-back eventually forging himself a cultish reputation as 'the underrated one' – and winning hearts and minds by being the only one to bear the weight of his England shirt on big occasions. Wayne Rooney will retire as the all-time leading scorer for the England national team and the country’s most decorated club. Even Michael Owen, the great white hope whose career fizzled out, has, through his endeavours in St Etienne and Cardiff, contributed two truly canonical moments to British football's recent past.

Silky simplicity

Ferdinand may not boast any of these bespoke honours, and yet in some ways he is the most unique of the lot. Ferdinand – with the possible exception of Cole – is alone among England’s great underachievers in that he cannot be accused of British football’s most widely-diagnosed pitfall: the priority of clout over craft, chaos over calm. While the successes of Lampard, Terry, Rooney and Gerrard are all founded on a central pillar of sweat, graft and clenched fists, Rio's game was based around quiet assurance, silky simplicity and near-constant exuding of harmony. By his own admission Ferdinand defended according to the 'clean shorts' mantra: the idea that, while being prepared to lunge around the goalmouth to stave off trouble is handy in a defender, it’s far safer never to get yourself in trouble in the first place.

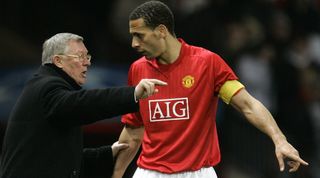

It’s a method that ensured him as a worthy heir to Jaap Stam’s berth – and it's telling that Alex Ferguson, whose dealings with Stam demonstrate his proudly cut-throat approach to selling off star names, never saw it necessary to jettison Ferdinand. “The best I’ve played with” was the view of Gary Neville, who was part of the 2008/09 defence whose staggering record of 11 consecutive clean sheets still stands.

Ferdinand was a leader, too. Again, not a practitioner of the tub-thumping, grandstanding brand of leadership at which English footballers so excel. Instead, he was the sort of captain who led by example without that example having to be an ostentatious display of machismo. Ironically for a player who spent his early years being widely derided for an apparent lack of intelligence (a perception largely put to bed by his outings on the pundits’ sofa), Rio is perhaps his generation’s principal proponent of brains over bravura.

Too easy

The most likely reason behind English football’s relative disregarding of Ferdinand is the simple fact that his club career didn’t encompass the grand power shifts of his rivals

Perhaps it's exactly this distinctiveness that is in fact responsible for the lack of plaudits received upon his retirement. Perhaps two decades of unruffled, unfussy proficiency left a lesser impression on British sport than the sweat-drenched efforts of his peers.

There is a strand of theory, too, which argues that Ferdinand, resplendent a defender as he was, never quite fulfilled his initial promise – that the forward-probing instincts and ball-playing ability which marked him out as a youngster were too readily coached out of him at Old Trafford, and that, rather than England’s answer to Beckenbauer or Baresi, he simply became a brick wall.

This is perhaps true, but it is rather speculative grounds for criticism. It also hints at various factors outside of Ferdinand’s control – namely, British football’s quashing of defensive creativity and the upsurge in risk-averse conservatism which marked Ferguson’s later years at Old Trafford.

But the most likely reason behind English football’s relative disregarding of Ferdinand is the simple fact that his club career didn’t encompass the grand power shifts of his rivals. Gerrard’s status as club emblem hinges to an extent on Liverpool’s retreat from football’s power base – his club’s decline saw the value of his loyalty ascend – while the careers of Lampard and Terry have come to symbolise the petrodollar-fuelled new world order brought about by Roman Abramovichs’s Chelsea.

Ferdinand has never been the protagonist of any such tectonic drama: he joined Manchester United as a world-class centre-half when the club was a giant trophy-gathering machine, and the two remained in much the same state for almost all of their time together. Ferdinand was no agent of change, nor a symbol of anything greater or grander than himself. Apart from his latter-day tainting-by-association at QPR, Ferdinand’s narrative is one of simple and lasting continuity – which, as any screenwriter will tell you, is no narrative at all.

But whatever the newspaper headlines and television promos suggest, football is not Hollywood, and so Ferdinand’s career needn’t be assessed on grounds of drama or storyline. Of England’s gradually departing Golden Generation, he should be counted up there with the best of them.

Most Popular